Anti-Roma racism has long been normalized and interwoven within the fabric of systems, societies, and interactions of liberal societies. It has endured not only through overtly violent racist laws, policies, behaviors, and actions, but also through veiled, unintentional, or implicit gadjikane (or non-Roma) power, advantages, and privileges in cultural, social, political, and economic spheres. In particular, gadjikane—gadjo-led and gadjo-normative—politics and policymaking have been fundamental underpinnings and protectors of this web of anti-Roma oppression.

Neglect and erasure, although not overtly or consistently intentionally racist, have long been systematically applied in politics, law, and policymaking. Gadjoness, meanwhile, is a major factor in the persistent failure of policies and laws to produce social change in major areas of interest for Roma individuals and families.

As Acemoglu and Robinson suggest in Why Nations Fail? and as I discuss in a 2017 article, it is crucial to analyze who makes decisions and why these people decide to do what they do and how decisions are made. Thus, I first discuss gadjo-led power and identify categories of gadjikane elites involved in politics and policymaking that impact Roma people. Then, I unpack gadjikane patterns in the making and implementation of both targeted Roma policy and ethno-neutral universal policies and laws.

When discussing the question of Who, it is inevitable to reproduce structural injustices and racist ideologies and tropes through policies and laws within a geographical context shaped by gadjoness and gadjikani hegemony. Those wielding power to decide over law, policies, budgets, and narratives—such as politicians, law and policymakers, discipline experts, and knowledge producers—are predominantly gadjikane elites who experienced and imagined the world through the gaze of gadjoness.

Gadjikane political leaders and decision-makers hold influence and power not only over ethno-neutral/silent universal policies but also over the creation of targeted Roma inclusion policies. This influence persists despite the establishment of governmental agencies dedicated to Roma issues and the engagement of Roma leaders in these processes.

The political and policymaking power over Roma agendas has been exercised by politicians across a broad spectrum of views. I will use Ibram Kendi’s categories regarding racial inequities in the United States, which include anti-racists, assimilationists, and segregationists. That being said, I’m more interested in perspectives, which I view as falling along a spectrum rather than being fixed categories of people. The anti-racist perspective approaches racial disparities through an anti-racist lens that focuses on dismantling racism. The assimilationist perspective acknowledges that racial disparities are tied to discrimination, but it also partially blames or questions oppressed people themselves. Lastly, the segregationist perspective puts the whole blame on the victims of racial disparities themselves for their circumstances.

Partly, the political and policymaking power over Roma agendas has been exercised by gadjikane elites with explicitly segregationist views and agendas that harm Roma people through law and policymaking. In the past few decades, some well-positioned politicians, known for their explicit racist views against Roma, have contributed to the formulation of and discussions about both ethno-neutral and targeted Roma policies.

Embodied Power in Politics and Policymaking

Embodied power and prestige manifest across a broad spectrum of state politics and policymaking, as well as institutions and politics. As already discussed, those in power can largely construct and advance dominant groups’ demands, norms, and interests in all spheres of politics and policy. These demands, norms, and interests often seem or are crafted as raceless, neutral, general, and universal. Yet they usually employ white and gadjikani normativity and, thus, exclude or diminish the rights and worth of the powerless and the historically oppressed.

Historically, elite white cis men have been the architects of privileges and rights in Europe. This remains true in the texts and practices of liberal democracies that formally defend and protect equality and individual rights. Mary Hawkesworth theorizes embodied power as:

[T]he role of the state in producing and sustaining inequalities is made inconceivable by the very notion of formal equality and legal neutrality. Systematic oppression is reduced to private troubles, which the self-determining individual is expected to rise above. By minimizing persistent structural constraints, individualism masks the contradictions that arise when formal equality coexists with systemic mechanisms of exclusion.

In liberal democracies, the individual who is to be protected and valued, or to be treated as equal, has always had the features of the white cis European man, which has been taken as the norm, the standard. For example, France, the country of egalité, no minorities, and all French people, markets itself as a model of racial/ethno-neutrality and equality in its laws and public policies. In practice, however, the reality is quite different. Punitive laws, policies, and practices do target marginalized and racialized groups, although they don’t necessarily name those groups. Black and North African youths are “much more likely to be stopped by police in France’s equivalent of stop-and-frisk.” France has long debated the ban on veils in public schools, a measure that essentially targets Muslim girls. President Jacques Chirac defended that ban as a tool to ensure a unified, secular France: “In all conscience, I consider that the wearing of clothes or signs which conspicuously denote a religious affiliation must be prohibited at school.”

Although France refuses to acknowledge the specific needs, challenges, and histories of its minority and historically oppressed groups, it still designs national laws, policies, and measures that further oppress and target the same groups. Yet, as Mary Hawkesworth argues, such “presumptions about colorblindness” or race neutrality, in conjunction “with assumptions about equal opportunity,” can “attribute differences in health, wealth, income, and mortality to the genetic lottery, or worse to cultural depravity or individual irresponsibility.”

Specifically, in the Roma case, elite gadjikane men have been the ones holding power over a vast spectrum of state actions, from anti-Roma to pro-Roma and Roma-silent (veiled as universal ethno-neutrality) laws, policies, and measures. Past and current universal laws, policies, and measures have traditionally been crafted by gadjikane leaders of European sovereigns and states, whether nationally or jointly, through multilateral or bilateral arrangements.

Across history, in the European polity, Roma people have never been the true architects of our own political and social decisions and choices. Thus, embodied gadjikani power becomes more apparent in the lack of or limited substantive Roma participation and fair Roma representation, as well as in practices of tokenism. Although well-intended, the making and implementation of both universal and inclusion agendas point to embodied power and a subtle form of coercive relations of power between gadje in power and Roma leaders and the “inferior or deviant status accorded to the subordinated group.”

Similar to the case of the other racialized and marginalized groups, the Roma individual has never been seen as a citizen to be protected, valued, or equal. In fact, under the veil of ethno-neutrality, punitive laws, policies, and practices also target Roma people. Continuing the earlier French example, in 2010, the government of France announced a biometric system to “allow us to detect repeated requests for repatriation assistance and help us prevent the undue payment of return aid to people who come once, twice,” as stated by Martine Rodier, the French minister of immigration and integration. Although the French government had to withdraw the proposal after the European Commission threatened infringement proceedings for violating the EU Freedom of Movement Directive, the proposed bill targeted Roma and other marginalized migrants. Laws, policies, or measures do not have to affirm an intent of coercion to target the subordinated group.

Thus, embodied power emerges in the capacity to make decisions for all and also specifically for Roma people, or the practice of doing so. This includes situations where those in power ignore, control, and/or tokenize Roma in decision-making or fail to decide and fail to invest in them in various spheres of society. Both the machinery of domination and the resistance to it push and pull the ways in which anti-Roma racism, its underpinnings, and manifestations reproduce, adjust, and reshape themselves in various times and spheres of politics and policies.

Embodied power and prestige also spread their tentacles in social structures, sites of arts, media, civil society, cultures, politics, institutions, interactions, and all spheres of life and influence. This web of hegemony gives meaning, integrates, and maintains disproportional advantages into the lives of gadje by dint of their identity markers. It feeds an enduring hierarchy of difference and worth. Embodied power and prestige can be strengthened or diluted in interaction with classism, patriarchy, ableism, or other oppressions. It produces mechanisms and practices of coercion and compliance in politics and policymaking.

Coercion and Compliance in Politics and Policymaking

Varied levels and dynamics of domination and subordination between the subaltern and in-power group—or between oppressed and oppressive sites—are enforced and normalized through embodied power. Those in positions of power have the tools and means to coerce the subaltern into control and domination. They can also secure the “willing compliance” of those who dominate.

The blurred line between coercion and willing compliance in politics and policymaking is exemplified by tokenism. In my work with Roma communities, I encountered Roma leaders who were willing to place the well-being and assets of Roma at risk so they could comply with the expectations of the gadjikane institutions they served and demonstrate their loyalty to them. This raises the question: why did they choose to do this when they weren’t necessarily coerced to?

Experience in politics and policymaking had taught Roma leaders about the invisible tentacles of embodied power and the unspoken rules to stay in the game. For a long time, explicitly or implicitly, those in positions of authority have sent a clear message to Roma leaders: adhering to their decisions takes precedence over seeking justice for Roma people and driving transformative change.

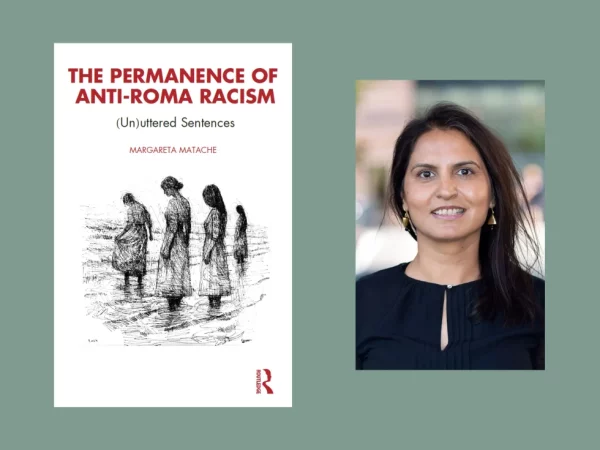

This is an excerpt from Margareta Matache‘s latest book, The Permanence of Anti-Roma Racism: (Un)uttered Sentences (Routledge, 2025).Email