PRIDE MONTH

Explained: The Stonewall Uprising And How June Became The Pride Month For LGBTQ Rights Movement

It's the 53rd anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, also called the Stonewall Riots, believed to have led to the larger LGBTQ rights movement.

\

Stonewall catalysed LGBTQ movement

There are multiple versions of the events at the Stonewall Inn, but all versions agree that the incident led to the larger the LGBTQ rights movement.

Michael Fader, a person present at the scene, was quoted in a book as saying that there was no going back from there.

"There was something in the air, freedom a long time overdue, and we’re going to fight for it. It took different forms, but the bottom line was, we weren’t going to go away. And we didn't," Michael was quoted as saying in the book Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution.

The Britannica noted, "Although there had been other protests by gay groups, the Stonewall incident was perhaps the first time lesbians, gays, and transgender people saw the value in uniting behind a common cause."

It further noted that there was a wider socio-political context to the incident.

"Occurring as it did in the context of the civil rights and feminist movements, the Stonewall riots became a galvanizing force," noted Britannica.

The rights movement became fierce with Stonewall

While homosexual organisations had been around in the United States since 1950s, they largely catered to the middle class and the majority of queer people didn't find their place there, said Aaron Lecklider, a professor at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. He termed Stonewall Uprising a "grassroot liberation".

He told Newsweek, "The grassroots liberation that emerged in and around Stonewall upended earlier efforts to fit in and perform good citizenship, drawing on the energy of a highly public revolt to join with revolutionary feminists, Black nationalists, and working-class revolutionaries in envisioning a better world.

"This was not the first time gay people had thrown in their lot with radicals. Many, including some of the architects of the 1950s homophile movement, were highly active in the Depression-era Communist Party. But the idea that gay people were better off dismantling the society that rejected them rather than begging for acceptance had finally entered into the mainstream currents of American culture."

Britannica also noted that Stonewall paved the way for new generation of radical groups such as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA).

"In addition to launching numerous public demonstrations to protest the lack of civil rights for gay individuals, these organizations often resorted to such tactics as public confrontations with political officials and the disruption of public meetings to challenge and to change the mores of the times. Acceptance and respect from the establishment were no longer being humbly requested but angrily and righteously demanded," as per Britannica.

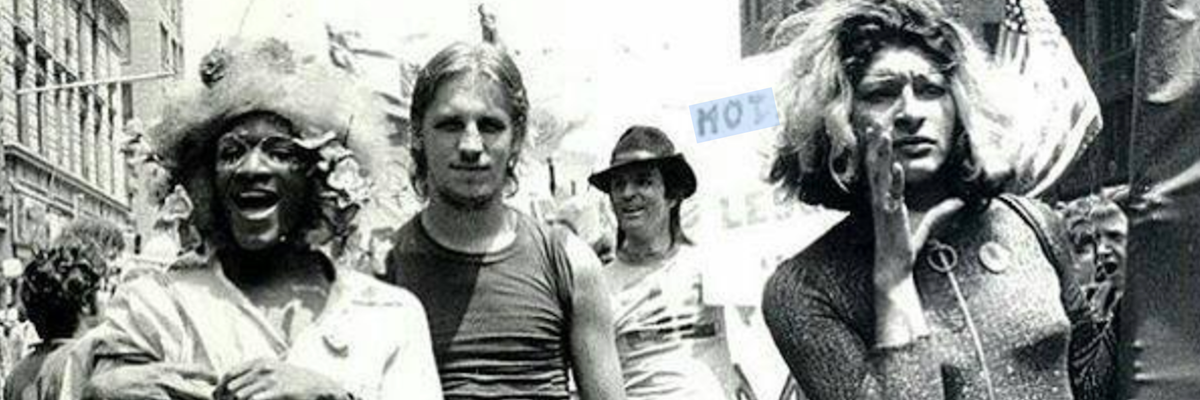

The First Pride Parade

The first Pride Parade was held in New York City on June 28, 1970 to mark the first anniversary of Stonewall.

By all estimates, there were 3-5,000 marchers at the inaugural Pride Parade in New York City, according to the Library of Congress.

Initially, the slogan was decided to be "gay power" rather than "gay pride", according to Britannica. Initially, it was a once-a-month parade in June, which evolved into a month-long affair over the years.

It adds that Gay Pride, or LGBTQ Pride, generally came to be celebrated in the United States on the last Sunday in June but the day expanded to become a monthlong event over the years.

Over the years, the Pride Month began to celebrated beyond the United States. Now there are parades, performances, and demonstrations during the Pride Month to mark the LGBTQ rights movement across the world.

Explained: The Stonewall Uprising And How June Became The Pride Month For LGBTQ Rights Movement

It's the 53rd anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, also called the Stonewall Riots, believed to have led to the larger LGBTQ rights movement.

\

Balloons in the form of the word PRIDE

Chris Sweda/Chicago Tribune via AP

INDIA

Outlook Web Desk

28 JUN 2022

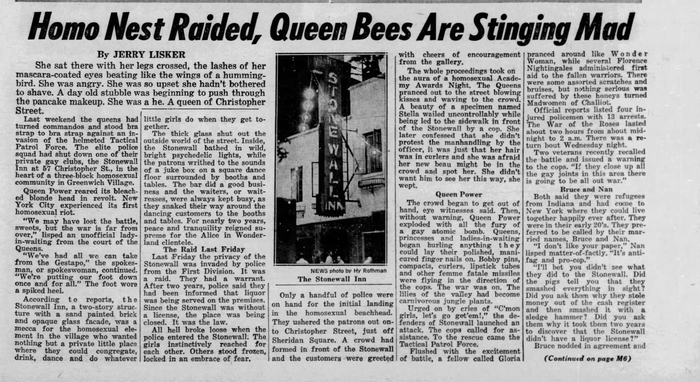

The police raided the Stonewall Inn in New York City on June 28, 1969. It was reportedly running without a liquor licence.

It was a time when homosexuality was a criminal offence. Gay bars were places where gay, lesbians, and others in the queer community socialised away from public harassment. The Stonewall Inn was one such place.

On June 28, 1969, the police arrested the employees for selling alcohol without a licence and assaulted some of the patrons there. It was the third such raid on the bars in the area, according to the Britannica Encyclopaedia.

However, the Stonewall Inn raid was different. People did not retreat or scatter as in the past. Rather, they began to jeer and jostle with the police as they put bar patrons in vans, as per Britannica. It adds that people threw beer bottles and debris at the police, forcing police personnel to barricade themselves behind the bar and call for reinforcements. As the police barricaded inside, around 400 people rioted outside and set the bar on fire.

It was the first of the confrontation with the police, which continued till July 3, 1969.

Five Poems On Growing Up As A Homosexual In Southern USA

Book Review: Exploring Queernormative In India’s Tribal Folktales

In Pictures: Pride Month In India And The World

The National Geographic noted, "It took hours for officers to clear the streets. The next night, thousands came to the Stonewall Inn to taunt the police. Clashes broke out again that night and sporadically in the days that followed."

INDIA

Outlook Web Desk

28 JUN 2022

The police raided the Stonewall Inn in New York City on June 28, 1969. It was reportedly running without a liquor licence.

It was a time when homosexuality was a criminal offence. Gay bars were places where gay, lesbians, and others in the queer community socialised away from public harassment. The Stonewall Inn was one such place.

On June 28, 1969, the police arrested the employees for selling alcohol without a licence and assaulted some of the patrons there. It was the third such raid on the bars in the area, according to the Britannica Encyclopaedia.

However, the Stonewall Inn raid was different. People did not retreat or scatter as in the past. Rather, they began to jeer and jostle with the police as they put bar patrons in vans, as per Britannica. It adds that people threw beer bottles and debris at the police, forcing police personnel to barricade themselves behind the bar and call for reinforcements. As the police barricaded inside, around 400 people rioted outside and set the bar on fire.

It was the first of the confrontation with the police, which continued till July 3, 1969.

Five Poems On Growing Up As A Homosexual In Southern USA

Book Review: Exploring Queernormative In India’s Tribal Folktales

In Pictures: Pride Month In India And The World

The National Geographic noted, "It took hours for officers to clear the streets. The next night, thousands came to the Stonewall Inn to taunt the police. Clashes broke out again that night and sporadically in the days that followed."

Stonewall catalysed LGBTQ movement

There are multiple versions of the events at the Stonewall Inn, but all versions agree that the incident led to the larger the LGBTQ rights movement.

Michael Fader, a person present at the scene, was quoted in a book as saying that there was no going back from there.

"There was something in the air, freedom a long time overdue, and we’re going to fight for it. It took different forms, but the bottom line was, we weren’t going to go away. And we didn't," Michael was quoted as saying in the book Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution.

The Britannica noted, "Although there had been other protests by gay groups, the Stonewall incident was perhaps the first time lesbians, gays, and transgender people saw the value in uniting behind a common cause."

It further noted that there was a wider socio-political context to the incident.

"Occurring as it did in the context of the civil rights and feminist movements, the Stonewall riots became a galvanizing force," noted Britannica.

The rights movement became fierce with Stonewall

While homosexual organisations had been around in the United States since 1950s, they largely catered to the middle class and the majority of queer people didn't find their place there, said Aaron Lecklider, a professor at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. He termed Stonewall Uprising a "grassroot liberation".

He told Newsweek, "The grassroots liberation that emerged in and around Stonewall upended earlier efforts to fit in and perform good citizenship, drawing on the energy of a highly public revolt to join with revolutionary feminists, Black nationalists, and working-class revolutionaries in envisioning a better world.

"This was not the first time gay people had thrown in their lot with radicals. Many, including some of the architects of the 1950s homophile movement, were highly active in the Depression-era Communist Party. But the idea that gay people were better off dismantling the society that rejected them rather than begging for acceptance had finally entered into the mainstream currents of American culture."

Britannica also noted that Stonewall paved the way for new generation of radical groups such as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA).

"In addition to launching numerous public demonstrations to protest the lack of civil rights for gay individuals, these organizations often resorted to such tactics as public confrontations with political officials and the disruption of public meetings to challenge and to change the mores of the times. Acceptance and respect from the establishment were no longer being humbly requested but angrily and righteously demanded," as per Britannica.

The First Pride Parade

The first Pride Parade was held in New York City on June 28, 1970 to mark the first anniversary of Stonewall.

By all estimates, there were 3-5,000 marchers at the inaugural Pride Parade in New York City, according to the Library of Congress.

Initially, the slogan was decided to be "gay power" rather than "gay pride", according to Britannica. Initially, it was a once-a-month parade in June, which evolved into a month-long affair over the years.

It adds that Gay Pride, or LGBTQ Pride, generally came to be celebrated in the United States on the last Sunday in June but the day expanded to become a monthlong event over the years.

Over the years, the Pride Month began to celebrated beyond the United States. Now there are parades, performances, and demonstrations during the Pride Month to mark the LGBTQ rights movement across the world.

Stormé DeLarverie performing in drag as the Master of Ceremonies in “The Jewel Box Revue” in 1960s Harlem.

Stormé DeLarverie performing in drag as the Master of Ceremonies in “The Jewel Box Revue” in 1960s Harlem.