SPECIAL THANKS TO

New Age "Asiatic" thought ... is establishing itself as the

hegemonic ideology of global capitalism. (Zizek)

SATURDAY, MARCH 18, 2006

FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE

Came across a book today that was published just a year ago by Cambridge University Press: Russian Roots of Nazism: White Émigrés and the Making of National Socialism 1917-1945. Bummer that it costs 80 bucks. No wonder nobody ever hears about these things.

Saul Friedlander of Tel Aviv University says...

Kellogg's work succeeds in introducing a dimension never so thoroughly explored: the essential impact on early Nazi world-view of ideological elements and political themes carried over to Germany by White-Russian émigrés.

Hmmm... And an Amazon reader-reviewer writes: "I strongly recommend this book which should be read alongside Karla Poewe New Religions and the Nazis" -- which I first mentioned a month ago in connection with the esoteric Yoga "scholarship" of Nazi German Faith Movement leader Jakob Wilhelm Hauer.

There is also much fascinating occult -- and just plain bizarre -- Russian background in the literally wonder-full Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia, including, lots of stuff about Madame Blavatsky.

Russia... double hmmm. In my post of 27 December last year, The Russians Are Coming, I included a quote from Gurdjieff: The Key Concepts about the proliferation of occultism in Russia. Here it is again...

Moscow and St. Petersburg were centres for the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century occult revival. From 1881 to 1918 thirty occult journals and more than 800 occult titles were published in Russia, reflecting interests in spiritualism, Theosophy, Rosicrucianism, alchemy, psycho-graphology, phrenology, hypnotism, Egyptian religions, astrology, chiromancy, animal magnetism, fakirism, telepathy, the Tarot, black and white magic, and Freemasonry (Carlson 1993: 22). Gurdjieff took notice of contemporary interests and presented his teaching accordingly. The cosmological form of his teaching was fully outlined between 1914 and 1918 in a form that takes account of the occult revival in Russia.Tournament of Shadows certainly corroborates that statement, and adds much detail. For instance (p. 234):

At Tashilhunpo, seat of the Tashi or Panchen Lama, [George] Bogle heard about "Shambul." Madame Blavatsky, founder of Theosophy, kept the legend alive, offering a geographic variation in The Secret Doctrine (1888), writing that "fabled Shambhallah, the headquarters of the Mahatmas, the sacred brotherhood" was located "somewhere in the Gobi."

To see where I, up-close-and-personal-like, came in on all this -- and part of the reason I'm writing this book -- clap your hands together while repeating "I want to Tinkerbell to live!" Then click the graphic...

Whoops, sorry. Looks like you didn't clap hard enough.

But back to Tournament of Shadows, the story continues (p. 242) with a description of a trip to Ceylon in 1891 by the young Tzar-to-be, Nicholas II, and his considerable entourage...

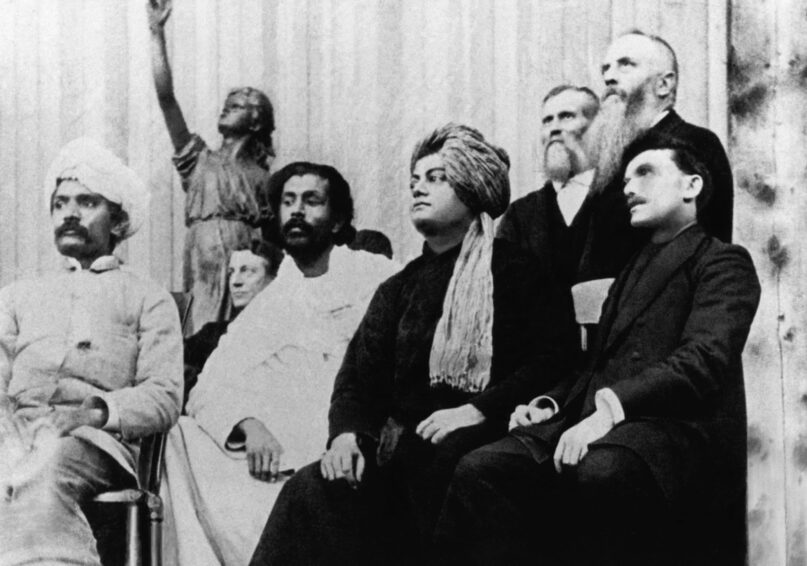

Now his imperial highness informs the Russian Consul in Colombo that he wishes to "have the honor of meeting" Colonel Olcott (1832-1907), a retired American officer who sports an enormous Santa Claus beard and is the champion of a worldwide Buddhist revival. It happens that Henry Steel Olcott, now resident in Colombo (the Sinhalese are Buddhists), is also the "chum" and associate of the Tsar's compatriot Helena P. Blavatsky. Together in 1875 they founded the Theosophical Society.

Imagine: Madame B. hangin' with the Tzar. Who knew?

The answer to that one, apparently, is damn few -- then or now. The history is there if you know what you're looking for and you dig for it like a demented dog. That would be me, rabidly indefatigable in the cause of grinding new lenses for a credulous world so awash in the occult it can no longer see the trees for the forest. Carl Solomon, I am with your mother, baby, standing in the shadows. Howl on that.

One more clip from Tournament, this one concerning the set designer (and so much more) for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes production of Rite of Spring (p. 450)...

The ballet's composer, Igor Stravinsky, claimed Roerich looked "as though he ought to have been a mystic or spy." In fact, recently opened intelligence archives suggest that at points in his career, he was both.

Nicholas Roerich was a worthy successor to Madame Blavatsky. A Russian mystic with a devoted following, he managed like her to baffle the intelligence departments on three continents. Like her, he was a Theosophist in quest of Shambhala who eventually made his home in India. But in two respects he surpassed HPB. Roerich gave his name to an an international treaty and in America he played an off-stage role in two Presidential campaigns.

And then there's a highly specialized treatise called No Religion Higher Than Truth: A History of the Theosophical Movement in Russia, 1875-1922 by Maria Carlson. Its publisher (Princeton UP) says...

Among the various kinds of occultism popular during the Russian Silver Age (1890-1914), modern Theosophy was by far the most intellectually significant. This contemporary gnostic gospel was invented and disseminated by Helena Blavatsky, an expatriate Russian with an enthusiasm for Buddhist thought and a genius for self-promotion. What distinguished Theosophy from the other kinds of "mysticism" -- the spiritualism, table turning, fortune-telling, and magic -- that fascinated the Russian intelligentsia of the period? In answering this question, Maria Carlson offers the first scholarly study of a controversial but important movement in its Russian context.

Carlson also wrote a paper called "Fashionable Occultism: Spiritualism, Theosophy, and Hermeticism in Fin-de-siecle Russia," which was collected in The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture. In this piece, Carlson writes:

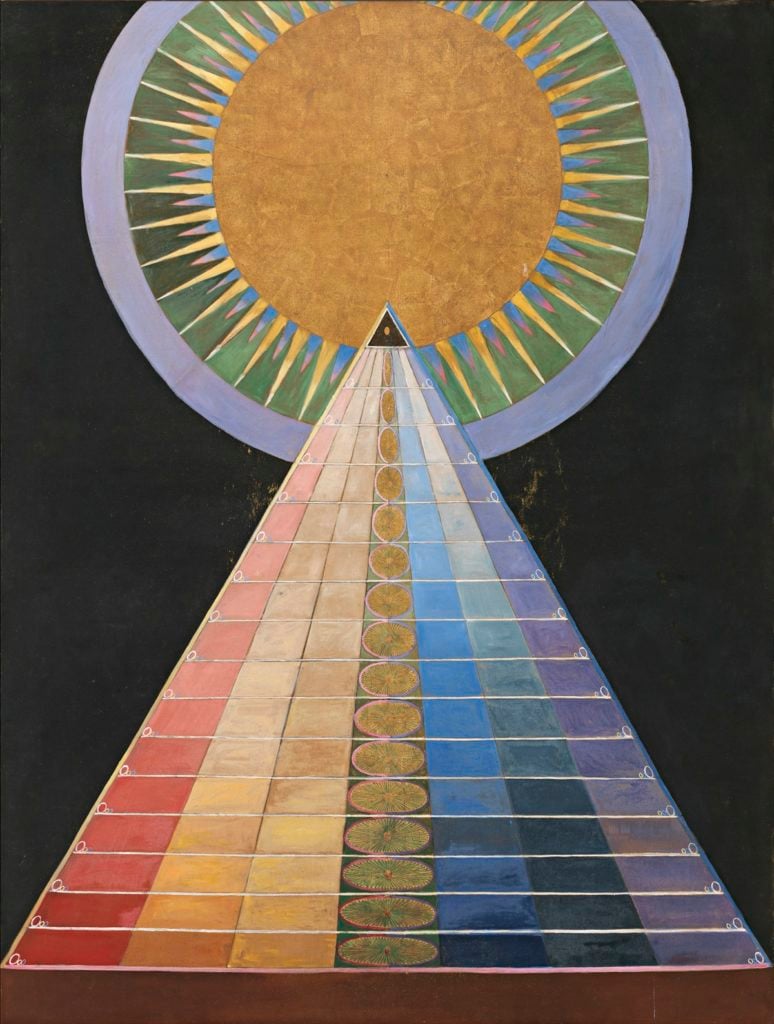

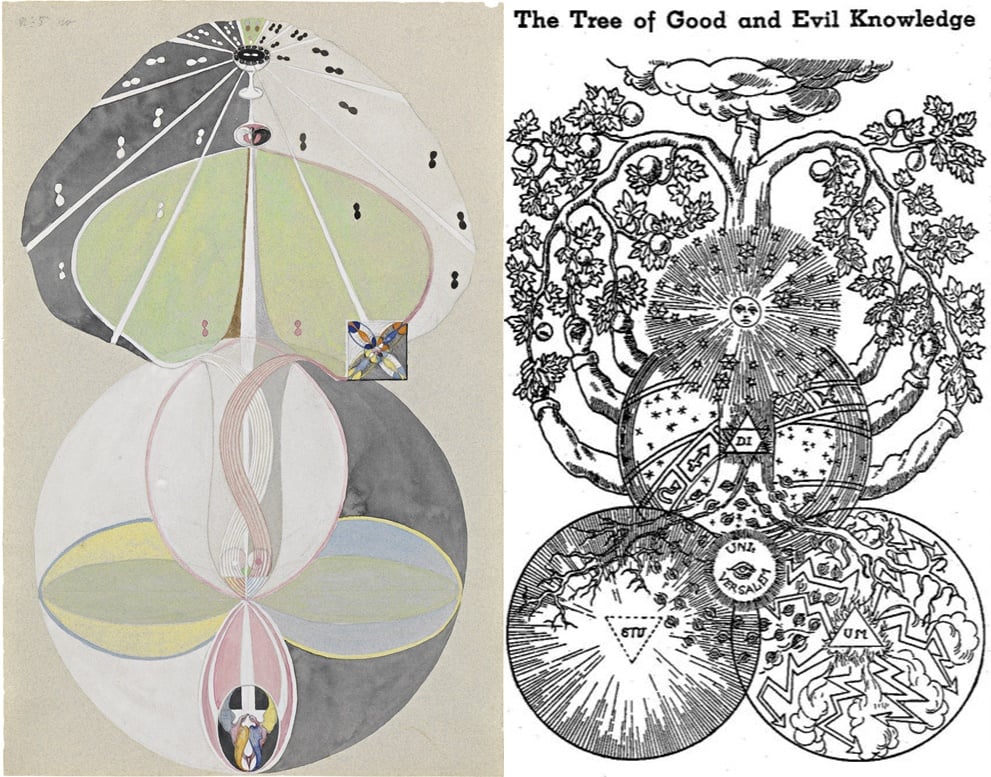

Mme Blavatsky's new Theosophy seemed to offer an alternative to the dominant materialism, rationalism, and positivism of the nineteenth century. Sometimes called Neo-Buddhism, Theosophy strikes the modern student as an eclectic, syncretic, dogmatic doctrine, strongly pantheistic and heavily laced with exotic Buddhist thought and vocabulary. Combining bits and pieces of Neoplatonism, Brahminism, Buddhism, Kabbalism, Rosicrucianism, Hermeticism, and other occult doctrines, past and present, in a frequently undiscriminating philosophical mélange, Theosophy attempted to create a "scientific" religion, a modern gnosis, based on absolute knowledge of things spiritual rather than on faith. Under its Neo-Buddhism lies an essentially Judeo-Christian moral ethic tempered by spiritual Darwinism (survival of those with the "fittest spirit" or most advanced spiritual development). One might describe Theosophy as an attempt to disguise positivism as religion, an attempt that was seductive indeed in its own time, in view of the psychic tension produced at the fin de siècle by the seemingly unresolvable dichotomy between science and religion.In The New York Review of Books (subscription required), Frederick C. Crews reviewed Madame Blavatsky's Baboon: A History of the Mystics, Mediums, and Misfits Who Brought Spiritualism to America. After describing the strange attraction Blavatsky held for William Butler Yeats -- who was similarly drawn to many forms of occultism and ritual magic -- Crews writes:

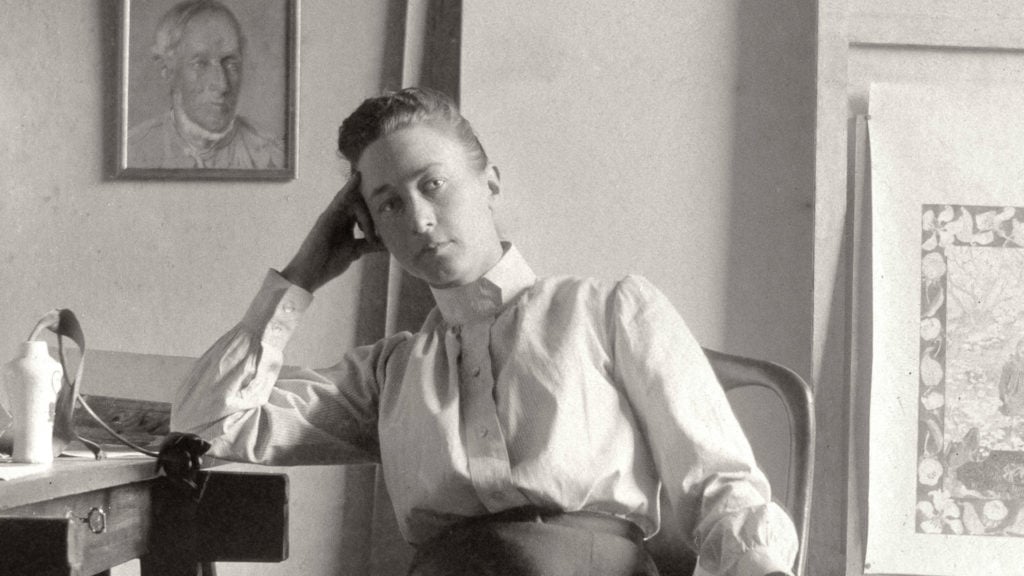

If Yeats's case were unique, we could dismiss it as a curious footnote to modern cultural history. But from the 1880s straight through the 1940s an imposing number of prominent figures, from Kandinsky and Mondrian through Gandhi and Nehru to Huxley and Isherwood, intersected the Theosophical orbit long enough to have their trajectory significantly altered by it.

Following is Publishers Weekly brief review of Blavatsky's Baboon...

Around the turn of the century, renegade Russian aristocrat Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky declared herself the chosen vessel of the wisdom of the East through her reputed contact with a dematerializing Tibetan master, who unveiled a Hidden Brotherhood located in the Himalayas and Egypt. The Theosophical Society, which she cofounded in 1875 in New York City with Civil War veteran Col. Henry Olcott, attracted a wide following with its amalgam of Hinduism, Buddhism and occultism. In this enormously entertaining, witheringly skeptical, highly colorful chronicle, British journalist Washington deflates the self-mythologizing and woolly philosophizing of theosophists and rival schools and gurus, including flamboyant Armenian-Greek mystic George Gurdjieff, Austrian philosopher/holistic healer Rudolf Steiner and Jiddu Krishnamurti, Indian ex-theosophist turned California sage. Those who came under their influence include Aldous Huxley, Katherine Mansfield, Christopher Isherwood, W.B. Yeats and Frank Lloyd Wright, making this a heady intellectual adventure as well as a clear-sighted saga of human foibles, charlatanry, bizarre antics and genuine spiritual hunger extending to New Age cults from the 1950s to the present.Am I making notes for a book that's been written dozens of times already? In my darker moments, I can begin to think so. But if that's so, why do so many people continue to be surprised by this sort of material? To wrap this up on no less depressing a note, in the end, it seems, people believe what they want to. Which I guess is why we live in the best of all possible worlds.

http://mysticbourgeoisie.blogspot.com/2006/03/from-russia-with-love.html