Arîfe Bekir: Women must shape the future of the new Syria

Arîfe Bekir, a member of the board of the Syrian Women's Council, called for women's unity and underlined the importance of anchoring women's rights in a new constitution.

NÛJIYAN ADAR

QAMISHLO

Thursday, 26 December 2024

Since the fall of the Syrian regime on 8 December, concerns about a deterioration in women's rights have increased. The Al-Qaeda offshoot HTS has taken power and, despite moderate words, has already implemented a number of misogynistic measures, such as expelling women from the judiciary. In an interview with ANF, Arîfe Bekir, a member of the board of the Syrian Women's Council, spoke about developments in the country from a woman's perspective.

Arîfe Bekir said that the conditions for women under the Baathist regime were extremely poor, contrary to what the regime reported, and added: "Although women's rights were formally anchored in the Syrian constitution, this had no consequences in practice. Women had no right to make their own decisions; their will was usurped. Although some women were able to hold important positions, this also took place in the shadow of the patriarchal mentality.”

The regime tortured active women and made them disappear

Bekir added: "The (Syrian) Women's Union was unable to be effective because it worked on the basis of the ideology of the Baath regime. The Syrian Women's Council applied to join this union, but were not accepted. In addition, many women were imprisoned by the regime and women who fought for their freedom were tortured. The fate of some women is still unknown. The aim was to break women's free will. Every single woman was deprived of her rights and forced to live within narrow limits."

2011 brought light and shadow for women

Especially after the uprisings in 2011, the situation of women changed in two ways. According to Bekir: "We can actually look at 2011 in two ways. On the one hand, the spread of the spark of the Rojava Revolution and the determined resistance of women are worth highlighting. With the revolutionary achievements of this period, women gained a say in all areas of life. Women were leading a revolution.

On the other hand, thousands of women were killed in clashes between the groups calling themselves the opposition and the Baath regime. There are many Syrian women whose fate is still unknown. In this war, the homes of thousands of women were destroyed, and women were displaced, killed and raped. The year 2011 and the period afterward was an extremely difficult time for women."

Practices in the occupied territories surpass the cruelty of the Baath regime

Bekir underlined that "women suffered heavily in the conflict between the interests of the mercenary groups and the Baath regime. These were groups that ostensibly set out to make a change in 2011, but occupied places like Afrin, Girê Spî, Serêkaniyê, al-Bab and Azaz. And they did not stop there, they continued to murder women, fill their prisons with women. We can say that every day in the occupied territories at least one woman is either murdered or raped. Young boys were forcibly recruited and forced to fight. Underage women were forced to marry. These groups supported polygamy. In fact, the practices of the groups that presented themselves as 'opposition forces' in the territories they occupied have surpassed the Baath regime in cruelty."

Our goal is the unity of women

On 8 September 2017, the Syrian Women's Council was founded. The aim was to unite all women in the country. Bekir explained the organization's intentions: "The Syrian Women's Council was founded with the aim of bringing women together across Syria, reaching out to all women in the country and promoting dialogue. The aim of this council is to create solidarity and unity by addressing the common problems of women. Women from different regions of Syria have the opportunity to support each other and build solidarity networks by sharing their experiences. As women from Syria, our priority is to guarantee women's freedom. In this context, we are actively fighting to defend women's social, economic and political rights. The protection, recognition and preservation of women's own identity are our priority.

Our goals include building a democratic and ecological society based on women's liberation and ensuring a solution to the crisis in Syria through democratic dialogue and decentralized systems. Our priorities include bringing freedom, democracy and justice to all ethnic, cultural and social identities, organizing and educating women and developing a free and equal understanding of life. By supporting the role of women in the new constitution and the dialogue process in Syria, we want to ensure women's rights in all areas. In this context, the implementation of international law, in particular Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, is of the utmost importance."

The resolution is about the position of women in conflicts. Among other things, it aims to guarantee the participation of women at all levels in peace processes, both in the negotiation and in the implementation of peace agreements. In addition, the resolution emphasizes the special need for protection of women and girls in armed conflicts. This particularly concerns protection against sexual and gender-based violence.

Women should write their own constitution

Bekir said that the time had come for the freedom of Syria's women and continued: "We are in a critical and extremely sensitive phase. This is the time of freedom and women. At such a time, all women must unite. All women must come together without distinction. Without the unity of women, without women standing shoulder to shoulder, there can be no freedom.

The main goal of the Syrian Women's Council is to empower women to assert their rights and free themselves from slavery. The future of the new Syria is extremely important for women. We support the construction of a new democratic, equal, just, peaceful and decentralized Syria, a country that guarantees women's rights. There will be a new constitution of Syria, and it is important that women's rights are enshrined in it. A constitution that is created on the basis of a patriarchal mentality will certainly not take women's rights into account. Therefore, women should write their constitution with their own hands."

Arîfe Bekir, a member of the board of the Syrian Women's Council, called for women's unity and underlined the importance of anchoring women's rights in a new constitution.

NÛJIYAN ADAR

QAMISHLO

Thursday, 26 December 2024

Since the fall of the Syrian regime on 8 December, concerns about a deterioration in women's rights have increased. The Al-Qaeda offshoot HTS has taken power and, despite moderate words, has already implemented a number of misogynistic measures, such as expelling women from the judiciary. In an interview with ANF, Arîfe Bekir, a member of the board of the Syrian Women's Council, spoke about developments in the country from a woman's perspective.

Arîfe Bekir said that the conditions for women under the Baathist regime were extremely poor, contrary to what the regime reported, and added: "Although women's rights were formally anchored in the Syrian constitution, this had no consequences in practice. Women had no right to make their own decisions; their will was usurped. Although some women were able to hold important positions, this also took place in the shadow of the patriarchal mentality.”

The regime tortured active women and made them disappear

Bekir added: "The (Syrian) Women's Union was unable to be effective because it worked on the basis of the ideology of the Baath regime. The Syrian Women's Council applied to join this union, but were not accepted. In addition, many women were imprisoned by the regime and women who fought for their freedom were tortured. The fate of some women is still unknown. The aim was to break women's free will. Every single woman was deprived of her rights and forced to live within narrow limits."

2011 brought light and shadow for women

Especially after the uprisings in 2011, the situation of women changed in two ways. According to Bekir: "We can actually look at 2011 in two ways. On the one hand, the spread of the spark of the Rojava Revolution and the determined resistance of women are worth highlighting. With the revolutionary achievements of this period, women gained a say in all areas of life. Women were leading a revolution.

On the other hand, thousands of women were killed in clashes between the groups calling themselves the opposition and the Baath regime. There are many Syrian women whose fate is still unknown. In this war, the homes of thousands of women were destroyed, and women were displaced, killed and raped. The year 2011 and the period afterward was an extremely difficult time for women."

Practices in the occupied territories surpass the cruelty of the Baath regime

Bekir underlined that "women suffered heavily in the conflict between the interests of the mercenary groups and the Baath regime. These were groups that ostensibly set out to make a change in 2011, but occupied places like Afrin, Girê Spî, Serêkaniyê, al-Bab and Azaz. And they did not stop there, they continued to murder women, fill their prisons with women. We can say that every day in the occupied territories at least one woman is either murdered or raped. Young boys were forcibly recruited and forced to fight. Underage women were forced to marry. These groups supported polygamy. In fact, the practices of the groups that presented themselves as 'opposition forces' in the territories they occupied have surpassed the Baath regime in cruelty."

Our goal is the unity of women

On 8 September 2017, the Syrian Women's Council was founded. The aim was to unite all women in the country. Bekir explained the organization's intentions: "The Syrian Women's Council was founded with the aim of bringing women together across Syria, reaching out to all women in the country and promoting dialogue. The aim of this council is to create solidarity and unity by addressing the common problems of women. Women from different regions of Syria have the opportunity to support each other and build solidarity networks by sharing their experiences. As women from Syria, our priority is to guarantee women's freedom. In this context, we are actively fighting to defend women's social, economic and political rights. The protection, recognition and preservation of women's own identity are our priority.

Our goals include building a democratic and ecological society based on women's liberation and ensuring a solution to the crisis in Syria through democratic dialogue and decentralized systems. Our priorities include bringing freedom, democracy and justice to all ethnic, cultural and social identities, organizing and educating women and developing a free and equal understanding of life. By supporting the role of women in the new constitution and the dialogue process in Syria, we want to ensure women's rights in all areas. In this context, the implementation of international law, in particular Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, is of the utmost importance."

The resolution is about the position of women in conflicts. Among other things, it aims to guarantee the participation of women at all levels in peace processes, both in the negotiation and in the implementation of peace agreements. In addition, the resolution emphasizes the special need for protection of women and girls in armed conflicts. This particularly concerns protection against sexual and gender-based violence.

Women should write their own constitution

Bekir said that the time had come for the freedom of Syria's women and continued: "We are in a critical and extremely sensitive phase. This is the time of freedom and women. At such a time, all women must unite. All women must come together without distinction. Without the unity of women, without women standing shoulder to shoulder, there can be no freedom.

The main goal of the Syrian Women's Council is to empower women to assert their rights and free themselves from slavery. The future of the new Syria is extremely important for women. We support the construction of a new democratic, equal, just, peaceful and decentralized Syria, a country that guarantees women's rights. There will be a new constitution of Syria, and it is important that women's rights are enshrined in it. A constitution that is created on the basis of a patriarchal mentality will certainly not take women's rights into account. Therefore, women should write their constitution with their own hands."

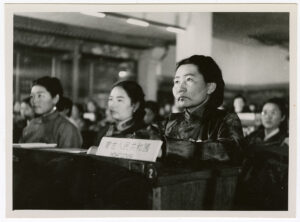

Women attending a conference titled "Building a Citizenship State Together Towards a United Syria where Everyone Wins" held in the Syrian city of Suwayda said that they will take an active role in building the future of Syria.

ANF

NEWS DESK

Wednesday, 25 December 2024, 23:45

A conference titled "Building a State of Citizenship Together Towards a United Syria where Everyone Wins" was held in Suwayda, a city in southwestern Syria with a large Druze population. Many citizens attended the conference and shared their thoughts on the future of Syria.

After the fall of the Baath regime and the coming to power of the Interim Government, women in Suwayda emphasized the need for women to participate in all aspects of life and play their political role.

Women must be equal to men

Sulwa Qasim told JINHA news agency: "I was one of the participants in the struggle from the first day of the movement in Suwayda and I have always stood side by side with men. My demand is not only for myself, but for all Syrian women to live in a 'country that benefits everyone'.

Suwayda added: "In this conference we called for the participation of women in all political and legal bodies in accordance with the Constitution and in proportion to their contributions in this field, taking into account that Syrian women are engineers, doctors, mothers, in the civil resistance and shoulder to shoulder with men in all fields of land, industry and life.

Women must not be excluded as second-class citizens. Women must have an equal and active role with men in building a new Syria. Women's participation in parliament and political life is a right that must never be compromised".

Women will play an important role

Lawyer Safaa Al Awam said: "Women are not half of society, but the whole of it, as they have proven their worth over the past 14 years, not only in the city of Suwayda, but in the whole of Syria and the world, because of that they will play an important role in drafting the constitution in the next phase."

Maysa Darwish said: "In the transitional phase, we should not ignore women who have participated in movements and revolutions in the past and present and who play a role in the political sphere, so we must make sure that they are included in all branches of the state, because they will work hand in hand with men in the new Syria to build a new Syria."

Lawyer Hanadi Hudhaifa said: "Since the beginning of the peaceful movement in Suwayda, women have played an active role, showing that women are not only for the home and kitchen."