Jason Kenney launches the Alberta witch hunt for ‘foreign-funded activists’

In tip of the hat to 1950s McCarthyism in United States, wags are calling inquiry the “Un-Alberta Activities Committee”

Alberta Premier Jason Kenney launched the “public inquiry into the foreign funding of anti-Alberta energy campaigns” Thursday afternoon. During this speech Kenney railed against the “misinformation” supposedly spread by pipeline and oil sands opponents, completely missing the irony that his own speech was filled with lies, half-truths, and errors of fact.

Long-term Calgary accountant Steve Allan will head up the inquiry. He is the board chair for Calgary Economic Development and “a respected volunteer and community leader who advocates for economic development, poverty reduction, sports and the arts,” according to the government’s press release

The question is, what exactly can Allan accomplish since he can only call witnesses from within Alberta and the objects of his ire – such as Tzeporah Berman – reside in British Columbia or Ontario? During Phase I, he will “conduct a paper review, interview witnesses and complete additional research” and in Phase II he “may hold a public hearing, if necessary.”

As the Canadian journalist who has reported most extensively about foreign-funded anti-pipeline and oil sands activism, I can assure readers there is very little “paper” for Allan to read. Sure, he can review Vancouver blogger Vivian Krause’s “research,” but as an acc0mplished and ethical professional, he will quickly recognize the limitations of her work: she has only done half the job.

For a decade Krause combed IRS databases searching for payments from American charitable foundations like the Tides Foundation and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund to Canadian environmental non-government organizations (ENGOs) like Greenpeace and Stand (formerly Forest Ethics), Berman’s ENGO. The available information included applications and covering letters from the foundations to the ENGOs.

That’s where she stopped.

During the interviews for my deep dive on her conspiracy narrative, Debunked: Vivian Krause’s Tar Sands Campaign conspiracy narrative, I interviewed over a dozen of the ENGOs and often asked them if Krause had followed up to ensure the funding was actually spent on activism, as she claims in her many blog posts and Postmedia op-eds. The answer was, no.

This email answer from Alison Henning, Tides Canada director of communications, is typical: “I slogged through a whole bunch of archived emails I could get access to back to 2014. Although in one email I found she asked a question about where the funding went, for the overwhelming majority, she would simply list a whole bunch of info she had collected, and then ask for us to reply and confirm it was correct.”

Sloppy research methodology then resulted in wrong conclusions, like lumping unabashedly activist ENGOs like Dogwood Initiative and Greenpeace in with Pembina Institute (a Calgary-based energy policy think tank) and Keepers of the Athabasca, which was involved in community education and environmental monitoring.

Even though Krause made the Tar Sands Campaign the centrepiece of her ENGO criticisms, she left out critical information that didn’t jibe with her conspiracy narrative. For instance, the Tar Sands Campaign received $40 million over 10 years, but after then Alberta Premier Rachel Notley launched the Climate Leadership Plan the US foundation funding dried up and in 2019 is less than $1 million, according to my interview with Berman.

How ironic that when Kenney said today that it “has seen foreign special interests secretively spending tens of millions of dollars to thwart Alberta’s economic development by landlocking our energy – but it stops now,” the US funding of the Tar Sands Campaign has virtually stopped all on its own.

That was hardly the Premier’s only faux pas.

For instance, he told reporters that the US foundations “enlisted and financed dozens of Canadian and American interest groups to execute these activities.” This is incorrect. Canadian First Nations, ENGOs, communities, and scientists began meeting in 2006 and they created the Tar Sands Campaign, as a coalition that ranged from 60 to 100 organizations over the years, in 2008 and Canadians were always in charge, despite having an American coordinator from 2008 to 2011.

Here’s another Kenney error of fact: “Vivian Krause has also revealed that since 2009, the American-based Tides Foundation and its Canadian affiliate gave at least 400 payments, totaling $25 million to Canadian American and European interest groups specifically to oppose the construction of pipelines in Canada.” Tides Canada is in no way affiliated with Tides Foundation, according to its CEO Joanna Kerr, they simply share a name because Canadian founders were impressed by the American example.

Furthermore, Tides Canada does not fund anti-pipeline activism, says Kerr, though it does fund pipeline-related projects, such as helping indigenous communities adapt to the economic and environmental effects of oil and gas extraction and transport.

Then there’s this whopper, which I have no qualms about calling a flat out lie: “The consequences for Albertans are plain to see: tens of thousands of job losses, thousands of business closures, a negative economic growth and massive increases in public debt.”

Alberta oil patch job losses began in early 2015 and were caused by the fall of crude oil prices from over $100 per barrel to less than $30 the following year, with heavy crude benchmark Western Canadian dipping below $20 in early 2016. Oil prices and oil prices alone were responsible for the devastation in the Alberta economy. Job losses due to constrained pipeline capacity didn’t begin until early 2018 after a November leak on the Keystone pipeline. WCS prices didn’t plunge again until late summer and throughout the fall as rising production finally overwhelmed the Canadian pipeline system.

Unfortunately, space prevents us from explaining the full catalogue of Kenney’s own misinformation campaign.

According to Doug Schweitzer, minister of justice and solicitor general, Allan will submit his report by July 2, 2020. In addition to the $2.5 million budget, the government will also provide administrative and technical support to the inquiry.

Like his boss, Schweitzer missed another irony: the inquiry will cost about three times the amount of the 2019 US foundation funding to the Tar Sands Campaign. Maybe less, though, if Allan skips the public hearing portion of the inquiry because he has no one to question since all the ENGOs are in Vancouver opposing the Trans Mountain Expansion pipeline project.

VIVIAN KRAUSE BACKGROUNDER

Vivian Krause | The Narwhal

Vivian Krause is a controversial writer critical of Canada's environmental charities. Krause claims American foundations are exercising foreign influence over ...

Corbella: Krause asks why Trudeau changed charity laws for activists ...

https://calgaryherald.com/.../corbella-krause-questions-why-trudeau-changed-charity-la...

2 days ago - Those are just two of the many questions asked by Vivian Krause during a sold out Calgary Chamber of Commerce luncheon Wednesday at ...

Vivian Krause (@FairQuestions) | Twitter

https://twitter.com/fairquestions?lang=en

The latest Tweets from Vivian Krause (@FairQuestions). Following the money behind environmental & political activism. Vancouver, British Columbia.

About Vivian Krause CONTACT INFO - Rethink Campaigns - TypePad

https://fairquestions.typepad.com/rethink.../about-the-author-vivian-krause.html

About Vivian Krause CONTACT INFO. At The Financial Post, they call me the girl who played with tax data and uncovered the foreign funding of Canadian green ...

Vivian Krause News, Articles & Images | Financial Post

https://business.financialpost.com/tag/vivian-krause

Read the latest news and coverage on Vivian Krause. View images, videos, and more on Vivian Krause on Financial Post.

Vivian Krause | DeSmogBlog

https://www.desmogblog.com/vivian-m-krause

ivian Maureen Krause is a Canadian researcher and blogger based in Vancouver. She began her blog Fair Questions in 2009 and has used it as a platform to ...

The inconvenient truth about Vivian Krause - EnergiMedia

https://energi.media › Markham on Energy

Unfortunately, they are not getting it from Vivian Krause, Licia Corbella, and the Calgary Herald ... In the first one, Krause refers to a cap on Alberta oil production.

Anti-pipeline campaign was planned, intended, and foreign-funded ...

https://www.jwnenergy.com/.../anti-pipeline-campaign-was-planned-intended-and-for...

Jun 27, 2019 - Weyburn – Vivian Krause has spent the better part of a decade digging into foreign funding backing campaigns to block Canadian...

Vivian Krause: The Cause of Oil Price Discounts - Canada Action

https://www.canadaaction.ca/vivian_krause_talks

Vivian Krause: The Cause of Oil Price Discounts. If you understand the importance of the energy sector to Canada's economy, and you know it has been

Alberta to hold $2.5-million public inquiry into funding for oil and gas foes

CALGARY – The Alberta government will hold a public inquiry into environmental groups that it says have been bankrolled by foreign benefactors hell-bent on keeping Canada’s oil and gas from reaching new markets while letting oil production grow unabated in the Middle East and the United States.

“They often say that sunlight is the best disinfectant. This public inquiry will be sunlight on the activities of this campaign,” Premier Jason Kenney said Thursday.

“It will investigate all of the national and international connections, follow the money trail and expose all of the interests involved.”

He said the inquiry — with a budget of $2.5-million — will find out if any laws have been broken and recommend any appropriate legal and policy action.

“Most importantly, it will serve notice that Alberta will no longer allow hostile interest groups to dictate our economic destiny as one of the most ethical major producers of energy in the world.”

Steve Allan, a forensic and restructuring accountant with more than 40 years of experience, has been named inquiry commissioner.

Allan’s ability to compel witness testimony and records is limited to Alberta.

But Justice Minister Doug Schweitzer said much of the information Allan will need is publicly available and he’ll be able to travel outside Alberta to gather more.

The first phase of the inquiry is to focus on fact finding, with public hearings to follow if necessary. Allan is to deliver his final report to the government in a year.

Opposition NDP member Deron Bilous said the inquiry is the equivalent of hiring someone to do a glorified Google search.

“This is a fool’s errand,” he said.

“I don’t believe this will help Alberta further its interests in accessing pipelines and expanding our market access.”

Kenney said deep-pocketed U.S. charities have been deliberately trying to landlock Alberta resources for years by funnelling money to an array of Canadian groups. Many of his assertions are based on the writings of Vancouver researcher Vivian Krause.

He blames those groups for the demise of several coast-bound pipelines that would have helped oilsands crude get to markets besides the U.S., as well as delays in building the Trans Mountain expansion to the west coast.

Krause said earlier this week that while the U.S. energy industry has benefited from anti-Canada “demarketing” campaigns, she has found no evidence commercial interests are involved.

She and Kenney both agreed it’s because Canada is an easy target.

“We’re very easy to pit against each other — Quebec, the West,” Krause said.

Kenney said Canada has been the kid in the school yard most easy to bully.

“I think they understood that this country amongst all of the major energy producers would be the most easily intimidated by this campaign,” he said. “And you know what? They were right.”

Kenney government launches inquiry into foreign-

funded groups that criticize Alberta’s oil industry

By Adam MacVicarDigital Journalist Global News

By Adam MacVicarDigital Journalist Global NewsGLOBAL NATIONAL: ALBERTA PREMIER LAUNCHES $2.5-MILLION INQUIRY INTO OIL

WATCH: Alberta Premier Jason Kenney is launching an inquiry into foreign-funded interest groups, which he says are targeting the province's oil sector. The $2.5-million initiative is supposed to focus on fact-finding, and may involve public hearings. But as Heather Yourex-West explains, critics question whether it will make a difference.

Alberta’s provincial government is launching an inquiry into foreign-funded interest groups with campaigns against Alberta oil.

Premier Jason Kenney made the announcement on Thursday, appointing forensic and restructuring accountant Steve Allen to commission the inquiry.The authority of the $2.5-million inquiry will be limited to Alberta and won’t be able to compel testimony from outside Alberta. However, there will be an information review, research and witness interviews involved.

The second phase of the inquiry could also include public hearings.

“There’s never been a formal investigation into all aspects of the anti-Alberta energy campaign,” Kenney said.

“The mandate for Commissioner Allan will be to bring together all of the information.”

RELATED

B.C. researcher argues anti-Alberta oil campaigns about protecting U.S. interests, not environment

B.C. researcher argues anti-Alberta oil campaigns about protecting U.S. interests, not environment

Alberta to offload crude by rail contracts, raises oil quotas for August

Alberta to offload crude by rail contracts, raises oil quotas for August

Higher oil prices, more tax income: Alberta ends 2018-19 with smaller deficit

Higher oil prices, more tax income: Alberta ends 2018-19 with smaller deficit

READ MORE: Kenney says higher risk tolerance, ability to act quickly key for Alberta energy ‘war room’

Kenney pointed to research conducted by Vivian Krause, whose studies have led her to believe the push against the oilsands is funded by American philanthropists in an effort to landlock Alberta oil so it cannot reach overseas markets, where it would attain a higher price per barrel.

According to Kenney, the inquiry will look at the broad picture of these interest groups, but will target groups funded by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Tides Foundation and the Sea Change Foundation.

“[The campaign’s] main tactics have been disinformation and defamation, litigation, public protests and political lobbying,” Kenney said.

There are currently no laws preventing environmental groups from from accepting donations from outside of Canada or for advocating for action on the environment and climate change.

LISENT Energy journalist Markham Hislop joins Danielle Smith to discuss the Kenney government’s new inquiry

Alberta’s provincial government is launching an inquiry into foreign-funded interest groups with campaigns against Alberta oil.

Premier Jason Kenney made the announcement on Thursday, appointing forensic and restructuring accountant Steve Allen to commission the inquiry.The authority of the $2.5-million inquiry will be limited to Alberta and won’t be able to compel testimony from outside Alberta. However, there will be an information review, research and witness interviews involved.

The second phase of the inquiry could also include public hearings.

“There’s never been a formal investigation into all aspects of the anti-Alberta energy campaign,” Kenney said.

“The mandate for Commissioner Allan will be to bring together all of the information.”

RELATED

B.C. researcher argues anti-Alberta oil campaigns about protecting U.S. interests, not environment

B.C. researcher argues anti-Alberta oil campaigns about protecting U.S. interests, not environment Alberta to offload crude by rail contracts, raises oil quotas for August

Alberta to offload crude by rail contracts, raises oil quotas for August Higher oil prices, more tax income: Alberta ends 2018-19 with smaller deficit

Higher oil prices, more tax income: Alberta ends 2018-19 with smaller deficitREAD MORE: Kenney says higher risk tolerance, ability to act quickly key for Alberta energy ‘war room’

Kenney pointed to research conducted by Vivian Krause, whose studies have led her to believe the push against the oilsands is funded by American philanthropists in an effort to landlock Alberta oil so it cannot reach overseas markets, where it would attain a higher price per barrel.

According to Kenney, the inquiry will look at the broad picture of these interest groups, but will target groups funded by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Tides Foundation and the Sea Change Foundation.

“[The campaign’s] main tactics have been disinformation and defamation, litigation, public protests and political lobbying,” Kenney said.

There are currently no laws preventing environmental groups from from accepting donations from outside of Canada or for advocating for action on the environment and climate change.

LISENT Energy journalist Markham Hislop joins Danielle Smith to discuss the Kenney government’s new inquiry

According to Kenney, the regulations were changed by the federal government lifting limits on political activity by these groups.

Kenney said he would seek advice from the commissioner on whether questionable spending by these groups prior to the amendments to the law could be a legal issue the province could address. He also vowed to bring in a law that bans foreign money from Alberta politics.

The premier said the inquiry isn’t an attack on free speech. He also said groups within Alberta could be subject to provide public testimony to the inquiry.

Kenney said the biggest question is around the interest these groups have in the Canadian energy sector.

“I believe having foreign interest groups funnel tens or perhaps hundreds of millions of dollars into a campaign designed massively to damage our vital economic interests is a matter of the greatest public concern,” Kenney said. “The energy industry and the emissions challenge are global. The question then is, why is the anti-energy campaign so overwhelmingly and disproportionately focused on one major producer?

“Why aren’t these groups running campaigns to block pipelines in the United States to the same extent that they have in Canada?”

READ MORE: Ottawa won’t rush into sale of Trans Mountain pipeline to Indigenous groups: Sohi

Federal Natural Resources Minister Amarjeet Sohi was in Calgary on Thursday for an address to the city’s chamber of commerce. He said foreign influence should be a concern but that he believes there should be reflection into why there has been a challenge to get pipelines built.

“We should always be concerned if foreign influence is trying to influence policy in your country, or the development of resources in your country,” Sohi said. “But I think we need to look inside within Canada: why are we not able to build pipelines?

I think you will find reasons within our own country for not moving forward with those projects.”

Not everyone is on board with the inquiry.

NDP economic development critic Deron Bilous called the inquiry a fool’s errand, and said the government is spending money on trying to find somebody to blame for the position the province is in.

“What the premier is trying to do is change the channel on his abysmal record thus far as far as job creation,” Bilous said. “What Albertans want to see is job creation. What they don’t want to see is a glorified witch hunt.”

According to Justice Minister and Attorney General Doug Schweitzer, the inquiry will take a year to complete and a report will be delivered to the government on July 2, 2020 with recommendations on how the government should proceed.© 2019 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.

Research project maps most powerful players in the fossil fuel industry and examines ‘pervasive’ reach into Canadian societyThe premier said the inquiry isn’t an attack on free speech. He also said groups within Alberta could be subject to provide public testimony to the inquiry.

Kenney said the biggest question is around the interest these groups have in the Canadian energy sector.

“I believe having foreign interest groups funnel tens or perhaps hundreds of millions of dollars into a campaign designed massively to damage our vital economic interests is a matter of the greatest public concern,” Kenney said. “The energy industry and the emissions challenge are global. The question then is, why is the anti-energy campaign so overwhelmingly and disproportionately focused on one major producer?

“Why aren’t these groups running campaigns to block pipelines in the United States to the same extent that they have in Canada?”

READ MORE: Ottawa won’t rush into sale of Trans Mountain pipeline to Indigenous groups: Sohi

Federal Natural Resources Minister Amarjeet Sohi was in Calgary on Thursday for an address to the city’s chamber of commerce. He said foreign influence should be a concern but that he believes there should be reflection into why there has been a challenge to get pipelines built.

“We should always be concerned if foreign influence is trying to influence policy in your country, or the development of resources in your country,” Sohi said. “But I think we need to look inside within Canada: why are we not able to build pipelines?

I think you will find reasons within our own country for not moving forward with those projects.”

Not everyone is on board with the inquiry.

NDP economic development critic Deron Bilous called the inquiry a fool’s errand, and said the government is spending money on trying to find somebody to blame for the position the province is in.

“What the premier is trying to do is change the channel on his abysmal record thus far as far as job creation,” Bilous said. “What Albertans want to see is job creation. What they don’t want to see is a glorified witch hunt.”

According to Justice Minister and Attorney General Doug Schweitzer, the inquiry will take a year to complete and a report will be delivered to the government on July 2, 2020 with recommendations on how the government should proceed.© 2019 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.

EDMONTON—A new database of the most powerful players in the energy industry paints a picture of a tight-knit network of oil companies, institutions and businesses with “pervasive” influence over Canada’s corporate, political and civil sectors.

The Corporate Mapping Project — a six-year joint initiative between the University of Victoria, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Alberta-based Parkland Institute — lists a “who’s who” of the energy industry in what is called the Fossil-Power Top 50 and explores their reach into wider society.

Conspiracy theory: Alberta oil blockaded by U.S. interests

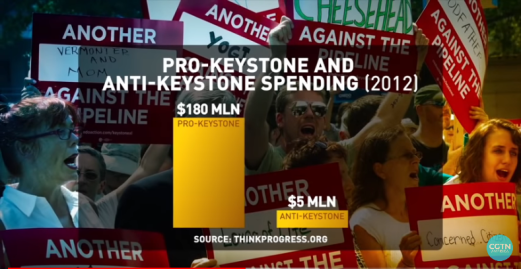

If a Billion-$ industry can be easily blockaded by the chump change of NGOs, perhaps oil and pipeline companies which can outspend them 100-1 need new CEOs?

The elephant in the room and the inconvenient truth for politicians who traffic in this tin-foil absurdity is that the majority of the oilsands is – or was before the downturn – foreign-owned. The Major oilsands investors have no problem getting their product to market because they are integrated with refineries in Texas and because they have pipeline and rail contracts to move their product.

The million-$-question is how are our Charities/NGOs able to allegedly target only the small producers in the oilsands?

Politicians like Jason Kenney use conspiracy theorists like Krause to achieve their own ends – perpetuating the fallacy of victimhood reels in the gullible and keeps them focused on the divisive deflection, not on holding the Government accountable for gutting fiscal capacity so that they can justify massive cuts in public services, de-regulation, & privatization.

1) It’s also a deflection from their failures. Northern Gateway failed in court because the Harper Government didn’t consult Indigenous groups. That failure also affected Kinder Morgan’s TMX pipeline. Mr Kenney was Harper’s lieutenant and after 10 yrs in his Government, he failed to get a pipeline to tidewater.

2) It’s a distraction to keep Albertans angry at the “other” and fixated on his promise that he alone will fix it. Where have we heard this before? Right … Trump!

3) Kenney’s 2019 election promise of setting up a $30 Million “war room” to crucify the pipeline opposition of our Charities/NGOs is a deflection from his previous Government’s failure with Vivian Krause as point person to do just that.

4) Harper’s Krause-inspired witch hunt against Charities for their political activities failed spectacularly when Charities won in court: CRA loses court challenge to its political-activity audits of charities.

Furthermore, new Legislation passed in December removes all limits on political activities of charities.

5) Harper’s witch hunt also drove millions in donations to the NGOs/Charities: Environment charities may benefit from new Alberta premier’s vow to fight them

The elephant in the room and the inconvenient truth for politicians who traffic in this tin-foil absurdity is that the majority of the oilsands is – or was before the downturn – foreign-owned. The Major oilsands investors have no problem getting their product to market because they are integrated with refineries in Texas and because they have pipeline and rail contracts to move their product.

The million-$-question is how are our Charities/NGOs able to allegedly target only the small producers in the oilsands?

Politicians like Jason Kenney use conspiracy theorists like Krause to achieve their own ends – perpetuating the fallacy of victimhood reels in the gullible and keeps them focused on the divisive deflection, not on holding the Government accountable for gutting fiscal capacity so that they can justify massive cuts in public services, de-regulation, & privatization.

1) It’s also a deflection from their failures. Northern Gateway failed in court because the Harper Government didn’t consult Indigenous groups. That failure also affected Kinder Morgan’s TMX pipeline. Mr Kenney was Harper’s lieutenant and after 10 yrs in his Government, he failed to get a pipeline to tidewater.

2) It’s a distraction to keep Albertans angry at the “other” and fixated on his promise that he alone will fix it. Where have we heard this before? Right … Trump!

3) Kenney’s 2019 election promise of setting up a $30 Million “war room” to crucify the pipeline opposition of our Charities/NGOs is a deflection from his previous Government’s failure with Vivian Krause as point person to do just that.

4) Harper’s Krause-inspired witch hunt against Charities for their political activities failed spectacularly when Charities won in court: CRA loses court challenge to its political-activity audits of charities.

Furthermore, new Legislation passed in December removes all limits on political activities of charities.

5) Harper’s witch hunt also drove millions in donations to the NGOs/Charities: Environment charities may benefit from new Alberta premier’s vow to fight them

On Keystone XL, spending of Proponents vs NGOs/Charities Opposed!

Revealed: Canadian government spent millions on secret tar sands advocacy

Harper government ads used image from pipeline company

Legislation passed in December 2018 removes all limits on political activities of charities

Despite the landmark court ruling and new Legislation passed in December that removes all limits on political activities of Charities; and, the fact BC residents cannot be compelled to testify for an AB inquiry, Premier Kenney announced a $2.5 million witch hunt against BC environmental groups.

Jason Kenney launches the Alberta witch hunt for ‘foreign-funded activists’

Stellar articles on Krause’s conspiracy:

Debunked: Vivian Krause’s Tar Sands Campaign conspiracy narrative

“Canadian money, not American, fueling anti-pipeline/oil sands activism”

“Krause’s conspiracy narrative is deeply flawed and she makes critical mistakes that essentially invalidate her argument.”

“Krause’s conspiracy narrative is deeply flawed and she makes critical mistakes that essentially invalidate her argument.”

Research project maps most powerful players in the fossil fuel industry and examines ‘pervasive’ reach into Canadian society

“That characterization of the level of influence the energy industry wields over government policy contradicts Alberta Premier Jason Kenney’s contention that the province is under siege by environmental groups who want to landlock Alberta’s oil….”

How Vivian Krause Became the Poster Child for Canada’s Anti-Environment Crusade

Krause took center stage as 3 parliamentary hearings and a Senate inquiry between Jan and Jun of 2012 and attempted to cast doubt on the integrity of Canadian environmental charities. Her claims critiquing foreign donations to environmental charities became the talking points of then PM Harper and cabinet. It prompted an $8 million witch hunt by the CRA of the “political activities” of charities – many of which were concerned about the impact of climate change with the massive oilsands expansion hinted at by Harper. Krause took credit for initiating these CRA audits while she received speaking fees from the oil/mining industries for laundering her conspiracy theories.

Feds also beneficiary of private U.S. grants

Conveniently ignored by Krause is how much money the Harper government received from some of the wealthiest private organizations in the U.S. including the same organizations that gave to Canadian environmental groups:

https://www.ctvnews.ca/feds-also-beneficiary-of-private-u-s-grants-1.7574

https://www.ctvnews.ca/feds-also-beneficiary-of-private-u-s-grants-1.7574

Rise of the new Alberta energy populism: Is oil/gas industry weaponizing Vivian Krause’s conspiracy nonsense?

“The Vancouver blogger almost singlehandedly feeds Alberta’s victimhood complex, which is one of the principal characteristics of modern populism.”

…

“So, welcome to populist politics Alberta-style, folks, where facts are optional and indignation is a constant state of mind, thanks in part to Vivian Krause. Don’t say that you weren’t warned.

https://energi.news/markham-on-energy/rise-of-the-new-alberta-energy-populism-is-oil-gas-industry-weaponizing-vivian-krauses-conspiracy-nonsense/

…

“So, welcome to populist politics Alberta-style, folks, where facts are optional and indignation is a constant state of mind, thanks in part to Vivian Krause. Don’t say that you weren’t warned.

https://energi.news/markham-on-energy/rise-of-the-new-alberta-energy-populism-is-oil-gas-industry-weaponizing-vivian-krauses-conspiracy-nonsense/

The inconvenient truth about Vivian Krause

Excerpt: “What I am disputing is the conclusions she draws from that research — conclusions that she shared on Wednesday in Calgary at the Indigenous Energy Summit, as reported by Corbella in her Herald column today.

“Krause says at the end of 2012 the Rockefeller Brothers specified that its money was to be used to “bring about a cap on the production of oil from Alberta.”

Sound familiar?

“Your premier put a cap on the oilsands,” Krause reminded the attentive crowd. “That’s exactly what the Rockefeller Fund funded the activists to do, was to pressure the government to put that cap on.”

Read those four sentences carefully.

In the first one, Krause refers to a cap on Alberta oil production. In the third and fourth sentence, a production cap magically becomes the Alberta government’s 100 megatonne oil sands emissions cap.

Notice the conflation between the oil sands and all oil extraction and between emissions and production.

Krause’s remarks are even contradicted by the Financial Post story that’s linked in Corbella’s column.”

… [emphasis added]

https://energi.news/markham-on-energy/__trashed/

Note Krause’s lack of logic: The Rockefellers divested from oil before Premier Notley was elected! Moreover, the Rockefellers’ fund doesn’t lobby people in other countries on how they should govern their Countries or their Provinces. She hasn’t a clue what philanthropy actually means!

https://www.rbf.org/mission-aligned-investing/divestment

“Krause says at the end of 2012 the Rockefeller Brothers specified that its money was to be used to “bring about a cap on the production of oil from Alberta.”

Sound familiar?

“Your premier put a cap on the oilsands,” Krause reminded the attentive crowd. “That’s exactly what the Rockefeller Fund funded the activists to do, was to pressure the government to put that cap on.”

Read those four sentences carefully.

In the first one, Krause refers to a cap on Alberta oil production. In the third and fourth sentence, a production cap magically becomes the Alberta government’s 100 megatonne oil sands emissions cap.

Notice the conflation between the oil sands and all oil extraction and between emissions and production.

Krause’s remarks are even contradicted by the Financial Post story that’s linked in Corbella’s column.”

… [emphasis added]

https://energi.news/markham-on-energy/__trashed/

Note Krause’s lack of logic: The Rockefellers divested from oil before Premier Notley was elected! Moreover, the Rockefellers’ fund doesn’t lobby people in other countries on how they should govern their Countries or their Provinces. She hasn’t a clue what philanthropy actually means!

https://www.rbf.org/mission-aligned-investing/divestment

Band leader counters column’s claims that U.S. interests fund anti-mine fight

“In Business in Vancouver’s December 13-19 edition, Vivian Krause continues to perpetuate conspiracy theories that make no sense and are deeply offensive to First Nations. (See “U.S. funding against Prosperity mine: $2 million for B.C. mining reform.”)

A former salmon farming industry executive, Krause has a number of theories that imply that First Nations do not speak for themselves. For example, she claims that opposition to salmon farming is a U.S.-funded plot to promote Alaskan wild salmon, when in fact it is driven by B.C. First Nations and non-aboriginal wild salmon fishermen seeking to preserve their resources and industries and by people from all walks of life who can see the overall reality and long-term impacts to wild salmon.

She also claims opposition to the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline is a plot by U.S. environmental foundations to secure tarsands oil for the U.S. by preventing its export to Asia.

Now, in her BIV column, she extends her conspiracy theories to support for mining reform in B.C. and specifically for the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s fight to protect its traditional lands and sacred Teztan Biny (Fish Lake), Yanah Biny (Little Fish Lake) and Nabas from one of B.C.’s worst-ever mine proposals – the Prosperity Mine project.

Krause implies that millions of dollars have poured into the Tsilhqot’in fight as a campaign from U.S. environmental funders to promote their country’s economic interests. This is laughable and deeply offensive.

Laughable because, in facing a company that has already spent $100 million on its mine campaign and a provincial government that spends taxpayer dollars to support this company, the Tsilhqot’in have worked on a shoestring to seek justice in this matter.

Deeply offensive because, as with all her conspiracy theories, Krause portrays us as pawns in some sinister plot to promote U.S. commercial interests. In doing so she demeans our sovereignty as First Nations and trivializes our serious issues, not to mention the honourable intentions of those who share our vision of a province that places respect for the environment and proven aboriginal rights above the interests of one mining company.

The facts are available to any trained researcher who genuinely seeks the truth. The campaigns Krause attacks as the commercial initiatives of foreign funders are all domestic issues that First Nations have long fought for. They are our issues.

Any funding we receive comes with no strings attached. Funders do not control or direct us. Any funding we can find is earned, in the sense that it is provided by those who believe that we deserve to be able to stand up for our rights and environment.

We are grateful to all funders, such as Victoria-based RavenTrust, one of the groups Krause singles out in her BIV article, for tirelessly seeking funds to help us. Much of the help we receive is time volunteered by Canadian groups and individuals, including many local residents.

If some of funding raised by RavenTrust comes from foreign sources, then what of it? This generosity is to support our story, not foreign interests.

Despite Krause’s insinuations, the Tsilhqot’in have not received millions of dollars, not even remotely close. We are constantly scrambling to find the resources to respond to the latest moves by the company and the province to press ahead with the discredited Prosperity Mine proposal.

We now face an environmental review for a Prosperity Mine proposal that the original review, based on studies by the company and Environment Canada, found to be worse than the plan rejected last year. This burden is a serious challenge for our people financially and from a community-health perspective as we struggle against a company, industry and provincial government that appear to have no shortage of funds or human resources.

We are proud that so many Canadians support us and that U.S. funders are willing to help based on the merits of our cases. We are also pleased that in the larger picture, we are not the only ones seeking to improve the archaic and unbalanced mining laws in B.C.

We are amazed any credence is given to the twisted logic that portrays our position as undemocratic and unpatriotic. Krause herself has admitted she has no evidence to support her claims, and experts such as the National Post’s Jonathan Kay, author of a book on conspiracy theories, dismiss her allegations.

Our proud Tsilhqot’in seek an honourable reconciliation of our aboriginal rights and title, beginning with respect for our deep cultural connection to Teztan Biny and the region surrounding it. We hope BIV readers will see through Krause’s sloppy research and disrespect for our autonomy and recognize that her article and this mine proposal should be dismissed.”

https://biv.com/article/2012/01/band-leader-counters-columns-claims-that-us-intere

A former salmon farming industry executive, Krause has a number of theories that imply that First Nations do not speak for themselves. For example, she claims that opposition to salmon farming is a U.S.-funded plot to promote Alaskan wild salmon, when in fact it is driven by B.C. First Nations and non-aboriginal wild salmon fishermen seeking to preserve their resources and industries and by people from all walks of life who can see the overall reality and long-term impacts to wild salmon.

She also claims opposition to the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline is a plot by U.S. environmental foundations to secure tarsands oil for the U.S. by preventing its export to Asia.

Now, in her BIV column, she extends her conspiracy theories to support for mining reform in B.C. and specifically for the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s fight to protect its traditional lands and sacred Teztan Biny (Fish Lake), Yanah Biny (Little Fish Lake) and Nabas from one of B.C.’s worst-ever mine proposals – the Prosperity Mine project.

Krause implies that millions of dollars have poured into the Tsilhqot’in fight as a campaign from U.S. environmental funders to promote their country’s economic interests. This is laughable and deeply offensive.

Laughable because, in facing a company that has already spent $100 million on its mine campaign and a provincial government that spends taxpayer dollars to support this company, the Tsilhqot’in have worked on a shoestring to seek justice in this matter.

Deeply offensive because, as with all her conspiracy theories, Krause portrays us as pawns in some sinister plot to promote U.S. commercial interests. In doing so she demeans our sovereignty as First Nations and trivializes our serious issues, not to mention the honourable intentions of those who share our vision of a province that places respect for the environment and proven aboriginal rights above the interests of one mining company.

The facts are available to any trained researcher who genuinely seeks the truth. The campaigns Krause attacks as the commercial initiatives of foreign funders are all domestic issues that First Nations have long fought for. They are our issues.

Any funding we receive comes with no strings attached. Funders do not control or direct us. Any funding we can find is earned, in the sense that it is provided by those who believe that we deserve to be able to stand up for our rights and environment.

We are grateful to all funders, such as Victoria-based RavenTrust, one of the groups Krause singles out in her BIV article, for tirelessly seeking funds to help us. Much of the help we receive is time volunteered by Canadian groups and individuals, including many local residents.

If some of funding raised by RavenTrust comes from foreign sources, then what of it? This generosity is to support our story, not foreign interests.

Despite Krause’s insinuations, the Tsilhqot’in have not received millions of dollars, not even remotely close. We are constantly scrambling to find the resources to respond to the latest moves by the company and the province to press ahead with the discredited Prosperity Mine proposal.

We now face an environmental review for a Prosperity Mine proposal that the original review, based on studies by the company and Environment Canada, found to be worse than the plan rejected last year. This burden is a serious challenge for our people financially and from a community-health perspective as we struggle against a company, industry and provincial government that appear to have no shortage of funds or human resources.

We are proud that so many Canadians support us and that U.S. funders are willing to help based on the merits of our cases. We are also pleased that in the larger picture, we are not the only ones seeking to improve the archaic and unbalanced mining laws in B.C.

We are amazed any credence is given to the twisted logic that portrays our position as undemocratic and unpatriotic. Krause herself has admitted she has no evidence to support her claims, and experts such as the National Post’s Jonathan Kay, author of a book on conspiracy theories, dismiss her allegations.

Our proud Tsilhqot’in seek an honourable reconciliation of our aboriginal rights and title, beginning with respect for our deep cultural connection to Teztan Biny and the region surrounding it. We hope BIV readers will see through Krause’s sloppy research and disrespect for our autonomy and recognize that her article and this mine proposal should be dismissed.”

https://biv.com/article/2012/01/band-leader-counters-columns-claims-that-us-intere

More RESOURCES

Canada upside down

Excerpts: “When scientists become the enemy of government, the language shifts, and suddenly they are “environmentalists” and “radicals” “bad” and “anti-Canadian.”

“This is a very bizarre twist, and here’s why:

Five years ago, the Harper government was thrilled to do business on exactly the model that it now vilifies as anti-Canadian money laundering. It entered into a conservation agreement to protect the Great Bear Rainforest in partnership with several American foundations in an agreement negotiated by Tides Canada.”

Five years ago, the Harper government was thrilled to do business on exactly the model that it now vilifies as anti-Canadian money laundering. It entered into a conservation agreement to protect the Great Bear Rainforest in partnership with several American foundations in an agreement negotiated by Tides Canada.”

Because it is here in Kitimat, and in BC’s protected forests and coastal waters, that the Enbridge pipeline proposal will meet its fiercest opposition.

Here’s a fair question. Does the location of the proposed Northern Gateway tanker route through the protected waters and coastline of the Great Bear Rainforest — funded by the Moore, Hewlett and Packard foundations in a Tides Canada deal — have anything to do with the fact that all of these organizations are now being pilloried by the very government that partnered with them?

Has the federal government decided to get out of the Great Bear Rainforest partnership, and calculated that the best way is to vilify and smear its own partners?

Just asking.

Meanwhile, it might be worth getting to know if we’ve really been palling around with terrorists.

With enemies like these, who needs friends?

Here then, are some of the American foundations which have been named and accused by our government of fraudulent money-laundering and ugly” “anti-Canadian” conduct:”

…. See article for list of organizations.

https://www.vancouverobserver.com/blogs/world/truth-behind-attack-charities-and-scientists-canada

Here’s a fair question. Does the location of the proposed Northern Gateway tanker route through the protected waters and coastline of the Great Bear Rainforest — funded by the Moore, Hewlett and Packard foundations in a Tides Canada deal — have anything to do with the fact that all of these organizations are now being pilloried by the very government that partnered with them?

Has the federal government decided to get out of the Great Bear Rainforest partnership, and calculated that the best way is to vilify and smear its own partners?

Just asking.

Meanwhile, it might be worth getting to know if we’ve really been palling around with terrorists.

With enemies like these, who needs friends?

Here then, are some of the American foundations which have been named and accused by our government of fraudulent money-laundering and ugly” “anti-Canadian” conduct:”

…. See article for list of organizations.

https://www.vancouverobserver.com/blogs/world/truth-behind-attack-charities-and-scientists-canada

“Truthiness” and the right’s attack on Canada’s charities

Excerpts: “Charity is about reducing poverty. Its [sic] about advancing education and …its [sic] about advancing religion,” she wrote on her blog.

As a factual statement, that’s flat wrong. As an opinion, it’s a dangerous fiction that should set off alarm bells, because this is precisely how to silence dissent.

On a per capita basis, Canada is second in the world — behind the Netherlands — in its charitable and volunteer activity.

No small potatoes, you might say.

If this looks a lot more like a molehill than a mountain, never you mind. It’s still political gold to purveyors of inflammatory rhetoric.

…

https://master.vancouverobserver.com/politics/commentary/stephen-colbert-truthiness-and-harper-governments-attack-canadas-charities

As a factual statement, that’s flat wrong. As an opinion, it’s a dangerous fiction that should set off alarm bells, because this is precisely how to silence dissent.

On a per capita basis, Canada is second in the world — behind the Netherlands — in its charitable and volunteer activity.

No small potatoes, you might say.

If this looks a lot more like a molehill than a mountain, never you mind. It’s still political gold to purveyors of inflammatory rhetoric.

…

https://master.vancouverobserver.com/politics/commentary/stephen-colbert-truthiness-and-harper-governments-attack-canadas-charities

The World According To Krause

This supposed scandal has been hiding in plain sight for almost a decade, and almost none of the key facts holds up to scrutiny. A veritable cottage industry has grown up promoting one of the most politically convenient conspiracy theories in recent memory.

https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/sandy-garossino/vivian-krause-us-oilsands-oil-sands-alberta-bc_b_2220651.html

https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/sandy-garossino/vivian-krause-us-oilsands-oil-sands-alberta-bc_b_2220651.html

How to recognize insurgents who threaten democracy.

Rick Mercer’s take-down of a foreign nationalism talking point is hilarious

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iZf5fC9v2qE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iZf5fC9v2qE

That Time a Foreign-Owned Newspaper Called Out Environmentalists for Taking Foreign Money to Fight a Foreign-Funded Pipeline

“… where’s the outrage over foreign ownership of Canadian natural resources?

There are plenty of really difficult conversations we need to have as Canadians about our energy future. How environmental non-profits are being funded frankly isn’t one of them. But hey, it’s an effective distraction technique.”

““Readers may find it difficult to believe that an industry which exported product worth $129 billion in 2014 — whose members include some of the biggest players in the national economy, players who could easily outspend American charities by a factor of a hundred — can feel like victims of the environmental movement, but they do,” Markham Hislop wrote.”

https://thenarwhal.ca/time-foreign-owned-newspaper-called-out-environmentalists-taking-foreign-money-fight-foreign-funded-pipeline

There are plenty of really difficult conversations we need to have as Canadians about our energy future. How environmental non-profits are being funded frankly isn’t one of them. But hey, it’s an effective distraction technique.”

““Readers may find it difficult to believe that an industry which exported product worth $129 billion in 2014 — whose members include some of the biggest players in the national economy, players who could easily outspend American charities by a factor of a hundred — can feel like victims of the environmental movement, but they do,” Markham Hislop wrote.”

https://thenarwhal.ca/time-foreign-owned-newspaper-called-out-environmentalists-taking-foreign-money-fight-foreign-funded-pipeline

Presentation suggests intimate relationship between Postmedia and oil industry

So it’s not okay for foreign charitable contributions to cross borders but it’s okay for an American-controlled Newspaper chain in Canada to collude with our oil industry?

“The ad proposal suggested “topics to be directed by CAPP and written by Postmedia,” with 12 single page “Joint Ventures” in the National Post, as well as 12 major newspapers including the Vancouver Sun, Calgary Herald and The Times Colonist.“

https://www.vancouverobserver.com/news/postmedia-prezi-reveals-intimate-relationship-oil-industry-lays-de-souza

“The ad proposal suggested “topics to be directed by CAPP and written by Postmedia,” with 12 single page “Joint Ventures” in the National Post, as well as 12 major newspapers including the Vancouver Sun, Calgary Herald and The Times Colonist.“

https://www.vancouverobserver.com/news/postmedia-prezi-reveals-intimate-relationship-oil-industry-lays-de-souza

Industry-Funded Vivian Krause Uses Classic Dirty PR Tactics to Distract from Canada’s Real Energy Debate

EXCERPT: “But as the blogger-turned-newspaper-columnist has run rampant with her conspiracy theory that American charitable foundations’ support of Canadian environmental groups is nefarious, she has continually avoided seeking a fair answer.

If Krause were seeking a fair answer, she’d quickly learn that both investment dollars and philanthropic dollars cross borders all the time. There isn’t anything special or surprising about environmental groups receiving funding from U.S. foundations that share their goals — especially when the increasingly global nature of environmental challenges, particularly climate change, is taken into consideration.

Despite this common-sense answer, Krause’s strategy has effectively diverted attention away from genuine debate of environmental issues, while simultaneously undermining the important role environmental groups play in Canadian society.

Creating Diversions a Trademark of Oil Industry Strategy

This diversion strategy is a well-known tactic of the oil industry. A strategy document leaked yesterday details how one of the world’s most powerful PR firms, Edelman, advised TransCanada to undermine opponents to the Energy East pipeline.

Edelman recommended TransCanada apply pressure to opponents by “distracting them from their mission and causing them to redirect their resources.” To achieve that, Edelman advises TransCanada to work with “supportive third parties who can in turn put the pressure on, particularly when TransCanada can’t.”

Sound familiar?”

If Krause were seeking a fair answer, she’d quickly learn that both investment dollars and philanthropic dollars cross borders all the time. There isn’t anything special or surprising about environmental groups receiving funding from U.S. foundations that share their goals — especially when the increasingly global nature of environmental challenges, particularly climate change, is taken into consideration.

Despite this common-sense answer, Krause’s strategy has effectively diverted attention away from genuine debate of environmental issues, while simultaneously undermining the important role environmental groups play in Canadian society.

Creating Diversions a Trademark of Oil Industry Strategy

This diversion strategy is a well-known tactic of the oil industry. A strategy document leaked yesterday details how one of the world’s most powerful PR firms, Edelman, advised TransCanada to undermine opponents to the Energy East pipeline.

Edelman recommended TransCanada apply pressure to opponents by “distracting them from their mission and causing them to redirect their resources.” To achieve that, Edelman advises TransCanada to work with “supportive third parties who can in turn put the pressure on, particularly when TransCanada can’t.”

Sound familiar?”

Convenient Conspiracy: How Vivian Krause Became the Poster Child for Canada’s Anti-Environment Crusade

EXCERPT: “An essential component of all public relations campaigns is having the right messenger— a credible, impassioned champion of your cause. While many PR pushes fail to get off the ground, those that really catch on — the ones that gain political attention and result in debates and senate inquiries — almost always have precisely the right poster child.

And in the federal government and oil industry’s plight to discredit environmental groups, the perfect poster child just so happens to be Vivian Krause. Krause describes herself as an “independent” researcher and a single mom asking “fair questions” about American funding of Canadian environmental groups. She blogged for many years in relative obscurity before becoming the federal Conservatives’ favourite attack dog.

Krause’s moment in the sun came in January 2012 when Joe Oliver, Canada’s then Natural Resources Minister, released his infamous letter decrying “foreign-funded radical” environmentalists for “hijacking” the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline review process.

Krause had primed the pump for the Conservatives to swoop in and achieve their goal — to discredit environmental groups by building a public narrative about them acting nefariously, thereby justifying spending millions of dollars on audits of charities’ political activities.

Never mind that philanthropic dollars cross international borders all the time. Never mind that the Northern Gateway proposal is sponsored by China’s state-owned oil company Sinopec, along with many other foreign oil companies. Never mind that there’s probably no more legitimate participation in a democracy than citizens signing up to speak at public hearings.

No, once you have a vendetta, inconvenient facts don’t matter. And Krause’s vendetta against environmental groups has been in the works for a long time — ever since she worked in public relations for the farmed salmon industry.”

And in the federal government and oil industry’s plight to discredit environmental groups, the perfect poster child just so happens to be Vivian Krause. Krause describes herself as an “independent” researcher and a single mom asking “fair questions” about American funding of Canadian environmental groups. She blogged for many years in relative obscurity before becoming the federal Conservatives’ favourite attack dog.

Krause’s moment in the sun came in January 2012 when Joe Oliver, Canada’s then Natural Resources Minister, released his infamous letter decrying “foreign-funded radical” environmentalists for “hijacking” the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline review process.

Krause had primed the pump for the Conservatives to swoop in and achieve their goal — to discredit environmental groups by building a public narrative about them acting nefariously, thereby justifying spending millions of dollars on audits of charities’ political activities.

Never mind that philanthropic dollars cross international borders all the time. Never mind that the Northern Gateway proposal is sponsored by China’s state-owned oil company Sinopec, along with many other foreign oil companies. Never mind that there’s probably no more legitimate participation in a democracy than citizens signing up to speak at public hearings.

No, once you have a vendetta, inconvenient facts don’t matter. And Krause’s vendetta against environmental groups has been in the works for a long time — ever since she worked in public relations for the farmed salmon industry.”

SOURCEWATCH: Vivian Krause

Excerpt: “Vivian Krause, a resident of North Vancouver, British Columbia, is a controversial Canadian blogger who claims to investigate the funding of environmental organizations to expose foreign influence over Canadian nonprofits. She has been paid for speaking events by right-wing think tanks, business groups, the mining industry, and the oil and gas industry, mostly in Canada. In the year 2012, more than 90% of Krause’s income came from speaking honorariums from the mining and oil and gas industries.[1]

…

Farmed Salmon Industry Employment

Between January 1, 2002 and October 13, 2003,Vivian Krause served as Corporate Development Manager (North America) for Nutreco Aquaculture, then the world’s largest salmon farming company.[5]”

…

Farmed Salmon Industry Employment

Between January 1, 2002 and October 13, 2003,Vivian Krause served as Corporate Development Manager (North America) for Nutreco Aquaculture, then the world’s largest salmon farming company.[5]”

Ethical Oil attack ads expose un-“fairness” of Vivian Krause

Excerpt: “Relationship between funders and fundees

“Indeed, when our Executive Director, Jessica Clogg, pointed out that we, and not our funders, set our priorities, Ethical Oil essentially accused her of lying on the basis that we had received money for a specific purpose.

…

Once we receive a grant from a foundation to carry out our work, we are obligated to use the money for the purposes for which we requested it, or to return it, but the workplan and deliverables are our own – we don’t take orders from the funders.

…

Krause and Ethical Oil accuse U.S. Foundations of ignoring their public purposes

The “foreign” interests that Krause and Ethical Oil are so incensed about are U.S. charities (unlike the U.S. and other foreign corporations that are investing so heavily in the tar sands). As such they are required by U.S. tax law to use their funds for purposes that are “public purposes”. And that is what they are doing by funding us (giving money to help protect the environment – a well recognized charitable purpose).

Ethical Oil alleges that these foundations are using their charitable funding in a direct attempt to enhance the position of U.S. energy interests by undermining Canadian oil interests.

…

[the elephant in the room is: why would U.S. corporations that are invested in the oilsands and integrated with refineries in Texas blockade their own interests?]

…

By all means, let’s have some fair questions.

Let’s ask who is funding Ethical Oil’s current attacks on Canadians who have signed up to express their opposition to the Enbridge Pipelines.

Let’s ask what influence big money – Canadian, U.S., Chinese or otherwise – is having on the Enbridge debate.”

…

https://www.wcel.org/blog/ethical-oil-attack-ads-expose-un-fairness-vivian-krause

“Indeed, when our Executive Director, Jessica Clogg, pointed out that we, and not our funders, set our priorities, Ethical Oil essentially accused her of lying on the basis that we had received money for a specific purpose.

…

Once we receive a grant from a foundation to carry out our work, we are obligated to use the money for the purposes for which we requested it, or to return it, but the workplan and deliverables are our own – we don’t take orders from the funders.

…

Krause and Ethical Oil accuse U.S. Foundations of ignoring their public purposes

The “foreign” interests that Krause and Ethical Oil are so incensed about are U.S. charities (unlike the U.S. and other foreign corporations that are investing so heavily in the tar sands). As such they are required by U.S. tax law to use their funds for purposes that are “public purposes”. And that is what they are doing by funding us (giving money to help protect the environment – a well recognized charitable purpose).

Ethical Oil alleges that these foundations are using their charitable funding in a direct attempt to enhance the position of U.S. energy interests by undermining Canadian oil interests.

…

[the elephant in the room is: why would U.S. corporations that are invested in the oilsands and integrated with refineries in Texas blockade their own interests?]

…

By all means, let’s have some fair questions.

Let’s ask who is funding Ethical Oil’s current attacks on Canadians who have signed up to express their opposition to the Enbridge Pipelines.

Let’s ask what influence big money – Canadian, U.S., Chinese or otherwise – is having on the Enbridge debate.”

…

https://www.wcel.org/blog/ethical-oil-attack-ads-expose-un-fairness-vivian-krause

An open letter to Canadian oil sands boosters: Stop whining and snivelling about environmentalists

Author: Markham Hislop.

Excerpt: “Stop thinking that the oil sands have some special dispensation that exempts them from criticism or opposition. They don’t.

….

Don’t demonize oil sands opponents – debate better, organize better, communicate better. The argument for oil sands development and the construction of pipelines is stronger, in my opinion, than the argument against.”

http://theamericanenergynews.com/markham-on-energy/open-letter-canadian-oil-sands-boosters-stop-whining-sniveling-environmentalists

Excerpt: “Stop thinking that the oil sands have some special dispensation that exempts them from criticism or opposition. They don’t.

….

Don’t demonize oil sands opponents – debate better, organize better, communicate better. The argument for oil sands development and the construction of pipelines is stronger, in my opinion, than the argument against.”

http://theamericanenergynews.com/markham-on-energy/open-letter-canadian-oil-sands-boosters-stop-whining-sniveling-environmentalists

Conspiracy theories are thrilling, but fall apart under scrutiny

Excerpt: “North Vancouver researcher Vivian Krause – who has a history of working for the salmon farming industry and for Conservative MP John Duncan – claims that the ongoing campaign to stop the expansion of oil tanker traffic on British Columbia’s coast is really a U.S. protectionist ploy to lock up the oil from the oilsands. In Krause’s conspiracy plot, the Big Bad Guys are U.S. charitable foundations, such as the Tides Foundation, the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and any Canadians fighting to stop oil tankers and the risk of oil spills they bring are unwitting dupes of these Machiavellian deep-pocketed U.S. funders.

…

Krause’s theory that U.S. funders aren’t interested in protecting the coast from oil tankers, but rather in maximizing the flow of oilsands crude to the United States, ignores an important fact -these same American foundations are also the main funders of the growing international campaign to stop the Keystone XL pipeline that would increase the flow of oilsands crude into the U.S. by almost one million barrels a day. Funny how this important fact wasn’t acknowledged by Krause, who has drawn praise for her research skills – but then a conspiracy theorist never let a contrary fact get in the way of a good theory.”

…

But what is also overlooked by the conspiracy theorists of both extremes is the fundamental role the growing network of British Columbians from all walks of life has in funding and politically driving the No Tankers campaign. Our No Tankers campaign has more than 75,000 supporters who donate and take action to stop oil tankers on B.C.’s coast.

It is ironic that we are being accused of being driven by U.S. interests when Dogwood Initiative’s founding mission is to reform the way in which British Columbia’s lands, waters and natural resources are managed by transferring power and control over a place to the people who actually live there. The right to decide is the basic right Dogwood Initiative has been fighting for since 1999 and our No Tankers campaign is grounded in the premise of “Our Coast, Our Decision.”

In the face of mounting pressure from the largest pipeline company in Canada, an undisclosed consortium of international oil companies funding Enbridge’s Northern Gateway project, and a pro-oil sands, pro-Northern Gateway federal and provincial government, we have helped build a broad grassroots movement of working families, First Nations governments, businesses, chambers of commerce, municipal governments, tourism operators and fishermen willing to take action to prevent oil tankers from threatening our coast. We solicit support for these efforts from anyone who shares our vision for the future of B.C. and who is willing to donate (as long as there are no strings attached). Fortunately, some Canadian and American foundations, along with a growing number of businesses and individual donors, almost all of whom are British Columbians, share our vision.”

…

Krause’s theory that U.S. funders aren’t interested in protecting the coast from oil tankers, but rather in maximizing the flow of oilsands crude to the United States, ignores an important fact -these same American foundations are also the main funders of the growing international campaign to stop the Keystone XL pipeline that would increase the flow of oilsands crude into the U.S. by almost one million barrels a day. Funny how this important fact wasn’t acknowledged by Krause, who has drawn praise for her research skills – but then a conspiracy theorist never let a contrary fact get in the way of a good theory.”

…

But what is also overlooked by the conspiracy theorists of both extremes is the fundamental role the growing network of British Columbians from all walks of life has in funding and politically driving the No Tankers campaign. Our No Tankers campaign has more than 75,000 supporters who donate and take action to stop oil tankers on B.C.’s coast.

It is ironic that we are being accused of being driven by U.S. interests when Dogwood Initiative’s founding mission is to reform the way in which British Columbia’s lands, waters and natural resources are managed by transferring power and control over a place to the people who actually live there. The right to decide is the basic right Dogwood Initiative has been fighting for since 1999 and our No Tankers campaign is grounded in the premise of “Our Coast, Our Decision.”

In the face of mounting pressure from the largest pipeline company in Canada, an undisclosed consortium of international oil companies funding Enbridge’s Northern Gateway project, and a pro-oil sands, pro-Northern Gateway federal and provincial government, we have helped build a broad grassroots movement of working families, First Nations governments, businesses, chambers of commerce, municipal governments, tourism operators and fishermen willing to take action to prevent oil tankers from threatening our coast. We solicit support for these efforts from anyone who shares our vision for the future of B.C. and who is willing to donate (as long as there are no strings attached). Fortunately, some Canadian and American foundations, along with a growing number of businesses and individual donors, almost all of whom are British Columbians, share our vision.”

Shooting the Messenger: Tracing Canada’s Anti-Enviro Movement

Excerpt: “Given the dismal reputation of the oilsands, the government had three options:

(a) clean them up by bringing in environmental legislation;

(b) discredit the people creating the negative image; or

(c) set up front groups to promote the industry, however dirty it may be.

In his discussion with Jacobson, Prentice suggested he would do

(a): “impose new rules on oil sands.” But he never did.

The federal government — which has promised to deliver oil and gas regulations since 2007 — offered no help.

Instead Prentice, along with the government of Alberta, got to work changing the oilsands’ image. The campaign began behind-the-scenes with intensive international lobbying focused on fighting the European Union’s proposed ‘dirty’ label for Albertan crude.

While those backroom meetings were taking place, another public strategy was being deployed to revive the image of the oilsands: demean those exposing the environmental disaster unfolding in Northern Alberta.”

https://thenarwhal.ca/shooting-messenger-tracing-canada-s-anti-enviro-movement

(a) clean them up by bringing in environmental legislation;

(b) discredit the people creating the negative image; or

(c) set up front groups to promote the industry, however dirty it may be.

In his discussion with Jacobson, Prentice suggested he would do

(a): “impose new rules on oil sands.” But he never did.

The federal government — which has promised to deliver oil and gas regulations since 2007 — offered no help.

Instead Prentice, along with the government of Alberta, got to work changing the oilsands’ image. The campaign began behind-the-scenes with intensive international lobbying focused on fighting the European Union’s proposed ‘dirty’ label for Albertan crude.

While those backroom meetings were taking place, another public strategy was being deployed to revive the image of the oilsands: demean those exposing the environmental disaster unfolding in Northern Alberta.”

https://thenarwhal.ca/shooting-messenger-tracing-canada-s-anti-enviro-movement

The Conservative government dropped the old trope of George Soros funding opposition to Canada’s oilsands when they found their Poster child to carry their placard into battle: Vivian Krause.

George Soros’ Open Society Foundation responds to Joe Oliver’s claims about enviro funding

““The Open Society Foundations are not funding environmental groups in Canada to oppose the Northern Gateway pipeline,” said foundation spokesperson Amy Weil.

When the Vancouver Observer reached Open Society to ask about their involvement, Weil said the organization was unaware of Oliver’s recent claims. According to Weil, their closest link to the pipeline debate is their support for groups working to achieve financial transparency in the oil industry.

“We do support some non-profit organizations working in Canada including Publish What You Pay, a global civil society coalition that campaigns for transparency in the payment, receipt and management of revenues from the oil, gas and mining industries,” said Weil.

She said, however, that the organization’s goal is related to fiscal transparency in the extractive sector—not to environmental issues.”

The Anti-Semitic Roots of Canadian Conservatives’ ‘Foreign Funded Radicals’ Attacks

“Vivian Krause, whose “research” is primarily cited in claims of “foreign funding,” hasn’t disclosed her own financing since 2011 (up until 2015, her Twitter account made critical references to Soros, but in recent years has tried to distinguish herself from such connections). Climate denying group “Friends of Science”—a frequent peddler of the “foreign funded” line—received a $175,000 donation from Talisman Energy in 2004 and listed in US coal company Peabody Energy’s 2016 bankruptcy documents as a creditor. Other astroturf groups like Oil Sands Action and Suits and Boots refuse to disclose sources of money.

FIFTH ESTATE: TransCanada and Keystone XL: The Money Pipeline

The Dark Money Krause claims blockades AB oil is reversed: untraceable American dark money was almost $200 Million in favor of Keystone.

Koch Brothers, Tea Party Billionaires, Donated To Right-Wing Fraser Institute, Reports Show

Krause also glosses over the fact that dark money flows into Canada in favor of pipelines. The toxic Koch brothers donate to the Fraser Institute & that’s proof that “foreign involvement in Canada’s environmental policy is a two-way street.”

Majority of Western Canada’s crude oil exports to US not exposed to record high discount between WCS and WTI

Krause also glosses over the fact the Majors in AB’s oilsands are mysteriously not blocked & get their product out of Alberta without problem. Majority of Western Canada’s crude oil exports to US not exposed to record high discount between WCS and WTI

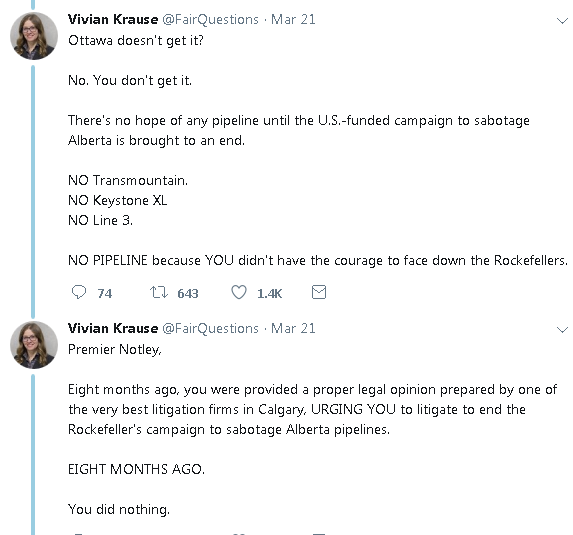

Canada’s Kellyanne Krause, a BC resident, trolls Premier Notley

HTML: FAIR QUESTIONS to Krause’s trolling of Premier Notley

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/uploads/2019/07/03/cpt504548325-0.jpg)

6 comments:

Herbal treatment is 100% guarantee for PENIS ENLARGEMENT , the reason why most people are finding it difficult to get a bigger and Erect Penis is because they believe on medical report, drugs and medical treatment, which is not helpful to Enlarge or Erect Penis . Natural roots/herbs are the best remedy which can easily Enlarge Penis and help you Last Longer on Bed. I am a living Testimony to this process Dr Aziba helped me with his Herbal Product which started to manifest within 7 days of use so i am writing his Contact for anyone who needs his Help in Enlarging of Penis and better Erection and also Weight Loss, Contact Dr via Email: Priestazibasolutioncenter@gmail.com and also via WhatsApp : +2348100368288

I got married 2 years ago and it just seemed that there was no excitement in my sex life. My dysfunction to perform to the best of my abilities in bed made it harder for my wife and me to have a good time during sex. And i was having the feelings that she may decide to get a divorce one day. I knew something had to be done in order to improve my sex life and to save my marriage because my marriage was already falling apart, so when i was on my Facebook page i came across a story of how Dr JOHN helped him enlarged his penis to 7ins better.so i Immediately copied the Email address of the Dr and explained to him my problem,he gave me some simply instruction which i must follow and i did easily and my friends Today, i am the happiest man on Earth, All Thanks to Dr JOHN for saving my marriage and making me a real man today.You can as well reach the Dr below for help on your problem, for he has the solution to all...

Email: DRJOHNTEMPLE@GMAIL.COM WHATSAPP NUMBER +2347064927420

I got married 2 years ago and it just seemed that there was no excitement in my sex life. My dysfunction to perform to the best of my abilities in bed made it harder for my wife and me to have a good time during sex. And i was having the feelings that she may decide to get a divorce one day. I knew something had to be done in order to improve my sex life and to save my marriage because my marriage was already falling apart, so when i was on my Facebook page i came across a story of how Dr JOHN helped him enlarged his penis to 7ins better.so i Immediately copied the Email address of the Dr and explained to him my problem,he gave me some simply instruction which i must follow and i did easily and my friends Today, i am the happiest man on Earth, All Thanks to Dr JOHN for saving my marriage and making me a real man today.You can as well reach the Dr below for help on your problem, for he has the solution to all...

Email: DRJOHNTEMPLE@GMAIL.COM WHATSAPP NUMBER +2347064927420

I got married 2 years ago and it just seemed that there was no excitement in my sex life. My dysfunction to perform to the best of my abilities in bed made it harder for my wife and me to have a good time during sex. And i was having the feelings that she may decide to get a divorce one day. I knew something had to be done in order to improve my sex life and to save my marriage because my marriage was already falling apart, so when i was on my Facebook page i came across a story of how Dr JOHN helped him enlarged his penis to 7ins better.so i Immediately copied the Email address of the Dr and explained to him my problem,he gave me some simply instruction which i must follow and i did easily and my friends Today, i am the happiest man on Earth, All Thanks to Dr JOHN for saving my marriage and making me a real man today.You can as well reach the Dr below for help on your problem, for he has the solution to all...

Email: DRJOHNTEMPLE@GMAIL.COM WHATSAPP NUMBER +2347064927420