World's oldest python fossil unearthed

The python fossils indicate these snakes

evolved in Europe.

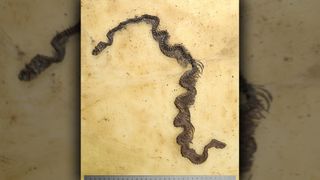

The 48 million-year-old fossil python discovered in Germany.

(Image: © Copyright Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung)

Scientists have discovered fossils of the oldest python on record, a slithery beast that lived 48 million years ago in what is now Germany.

Found near an ancient lake, the snake remains are helping researchers learn where pythons originated. Previously, it wasn't clear whether pythons came from continents in the Southern Hemisphere, where they live today, or the Northern Hemisphere, where their closest living relatives (the sunbeam snakes of Southeast Asia and the Mexican burrowing python) are found. But this newfound species — dubbed Messelopython freyi — suggests that pythons evolved in Europe.

"So far, there have been no early fossils that would help decide between a Northern and Southern Hemisphere origin," study co-researcher Krister Smith, vertebrate paleontologist at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Frankfurt, Germany, told Live Science in an email. "Our new fossils are by far the oldest records of pythons, and (being in Europe) they support an origin in the Northern Hemisphere."

Related: Image gallery: Snakes of the world

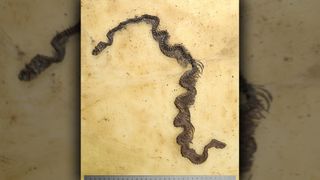

The 48 million-year-old fossil python discovered in Germany.

(Image: © Copyright Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung)

Scientists have discovered fossils of the oldest python on record, a slithery beast that lived 48 million years ago in what is now Germany.

Found near an ancient lake, the snake remains are helping researchers learn where pythons originated. Previously, it wasn't clear whether pythons came from continents in the Southern Hemisphere, where they live today, or the Northern Hemisphere, where their closest living relatives (the sunbeam snakes of Southeast Asia and the Mexican burrowing python) are found. But this newfound species — dubbed Messelopython freyi — suggests that pythons evolved in Europe.

"So far, there have been no early fossils that would help decide between a Northern and Southern Hemisphere origin," study co-researcher Krister Smith, vertebrate paleontologist at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Frankfurt, Germany, told Live Science in an email. "Our new fossils are by far the oldest records of pythons, and (being in Europe) they support an origin in the Northern Hemisphere."

Related: Image gallery: Snakes of the world

VIDEO https://www.livescience.com/oldest-python-snakes-on-record.html?jwsource=cl

The M. freyi fossils were found at Messel Fossil Pit, near Frankfurt, Germany. Formerly an oil shale mine, this site almost became a garbage dump in the 1970s. ("A big hole in the ground is a valuable commodity," Smith said.) But by then, the site was already known for its remarkable fossils dating to the Eocene epoch (between 57 million and 36 million years ago). So, in 1995 it became a UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) site. Fossils unearthed there include a pregnant mare, mating turtles and shimmering beetles.

Image 1 of 2

The first discovered fossil belonging to the newfound species Messelopython freyi. (Image credit: Copyright Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung)

A sketch (left) and photo of a skull (right) of one of the newly analyzed python fossils. (Image credit: Copyright Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung)

M. freyi would have been about the same size as today's small pythons, reaching nearly 3.2 feet (1 meter) in length and sporting about 275 vertebrae, the researchers said. The ancient python also sheds light on its relationship with boa constrictors.

In effect, the discovery shows that this early European python lived alongside boa constrictors, a startling find given that boas don't live anywhere near modern-day pythons. In general, boas live in South and Central America, Madagascar and northern Oceania, whereas pythons inhabit Africa, Southeast Asia and Australia. "This is one of the most exciting and intriguing aspects of the discovery of Messelopython," said study co-researcher Hussam Zaher, professor and curator of vertebrates at the Museum of Zoology at the University of São Paulo, in Brazil.

Researchers already knew that boas lived in Europe during the early Paleogene period, which lasted from 66 million to 23 million years ago. Now that it's clear pythons lived there too, it raises questions about how these "direct ecological competitors," which both squeeze prey to death, coexisted, Zaher told Live Science in an email.

RELATED CONTENT

—In photos: A tarantula-eat-snake world

—In photos: How snake embryos grow a phallus

—Photos: How to identify a western diamondback rattlesnake

This question may be answered by finding more early python and boa fossils, especially those with preserved stomach contents, he said. In addition, researchers can look to southern Florida, where python (Python molurus bivittatus and P. sebae) and boa (Boa constrictor) species coexist as invasive species. It's not yet clear whether the P. molurus bivittatus and B. constrictor living in the Sunshine State "are competing over resources or may be using slightly different microhabitat and preys," Zaher said. "A similar situation may have happened in Europe during the Eocene."

The study was published online Wednesday (Dec. 16) in the journal Biology Letters.

Originally published on Live Science.

PYTHON WORSHIP WAS THE FIRST RELIGION

The M. freyi fossils were found at Messel Fossil Pit, near Frankfurt, Germany. Formerly an oil shale mine, this site almost became a garbage dump in the 1970s. ("A big hole in the ground is a valuable commodity," Smith said.) But by then, the site was already known for its remarkable fossils dating to the Eocene epoch (between 57 million and 36 million years ago). So, in 1995 it became a UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) site. Fossils unearthed there include a pregnant mare, mating turtles and shimmering beetles.

Image 1 of 2

The first discovered fossil belonging to the newfound species Messelopython freyi. (Image credit: Copyright Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung)

A sketch (left) and photo of a skull (right) of one of the newly analyzed python fossils. (Image credit: Copyright Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung)

M. freyi would have been about the same size as today's small pythons, reaching nearly 3.2 feet (1 meter) in length and sporting about 275 vertebrae, the researchers said. The ancient python also sheds light on its relationship with boa constrictors.

In effect, the discovery shows that this early European python lived alongside boa constrictors, a startling find given that boas don't live anywhere near modern-day pythons. In general, boas live in South and Central America, Madagascar and northern Oceania, whereas pythons inhabit Africa, Southeast Asia and Australia. "This is one of the most exciting and intriguing aspects of the discovery of Messelopython," said study co-researcher Hussam Zaher, professor and curator of vertebrates at the Museum of Zoology at the University of São Paulo, in Brazil.

Researchers already knew that boas lived in Europe during the early Paleogene period, which lasted from 66 million to 23 million years ago. Now that it's clear pythons lived there too, it raises questions about how these "direct ecological competitors," which both squeeze prey to death, coexisted, Zaher told Live Science in an email.

RELATED CONTENT

—In photos: A tarantula-eat-snake world

—In photos: How snake embryos grow a phallus

—Photos: How to identify a western diamondback rattlesnake

This question may be answered by finding more early python and boa fossils, especially those with preserved stomach contents, he said. In addition, researchers can look to southern Florida, where python (Python molurus bivittatus and P. sebae) and boa (Boa constrictor) species coexist as invasive species. It's not yet clear whether the P. molurus bivittatus and B. constrictor living in the Sunshine State "are competing over resources or may be using slightly different microhabitat and preys," Zaher said. "A similar situation may have happened in Europe during the Eocene."

The study was published online Wednesday (Dec. 16) in the journal Biology Letters.

Originally published on Live Science.

No comments:

Post a Comment