Scientists Have Discovered an Entirely New Way Snakes Can Move, And It's So Weird

(Cell Press/YouTube)

NATURE

PETER DOCKRILL

11 JANUARY 2021

Scientists have identified an entirely new mode of snake locomotion. The newly documented climbing behaviour is difficult, but allows snakes to impressively shimmy up large, smooth cylinders.

Researchers have dubbed it 'lasso locomotion', because the snake climbs poles by lassoing its body around the cylindrical structures, gripping them tightly in a looped noose from torso to tail.

The phenomenon, which expands the known climbing repertoire of snakes, seems to let the brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis) ascend much larger smooth cylinders than any previously known climbing behaviour – and may constitute the first entirely new form of snake movement identified in recent history.

"For nearly 100 years, all snake locomotion has been traditionally categorised into four modes: rectilinear, lateral undulation, sidewinding, and concertina," a research team led by conservation biologist Julie Savidge from Colorado State University explains in the new paper.

Another kind of snake movement, slide-pushing, is also recognised by some in the scientific community as a distinct form of locomotion, and occurs on flat surfaces. At the same time, some have suggested existing categorisations should be more diverse than previously acknowledged.

In any case, lasso locomotion is quite different to all of the recognised forms of snake motion, and was a chance discovery made during a conservation project in Guam, where the brown tree snake – an invasive species accidentally introduced into the US island territory in the mid 20th century – has devastated local bird populations (and more besides).

While reviewing video footage of experimental metal baffle structures – designed to protect birds by preventing snakes from reaching sheltered bird boxes – the team noticed something unique.

"We had watched about four hours of video and then all of a sudden, we saw this snake form what looked like a lasso around the cylinder and wiggle its body up," wilderness medicine researcher Thomas Seibert explains.

"We watched that part of the video about 15 times. It was a shocker. Nothing I'd ever seen compares to it."

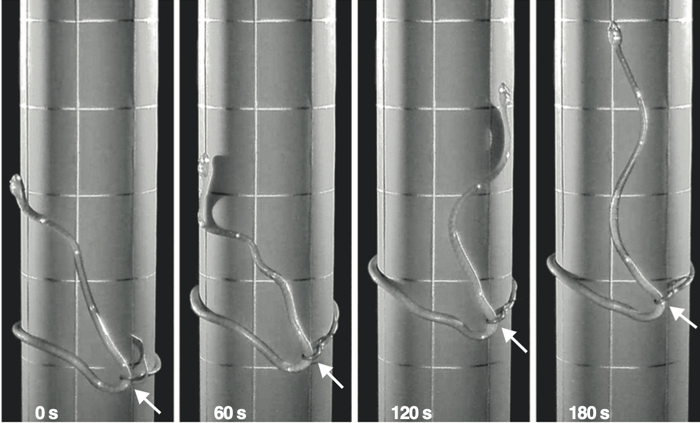

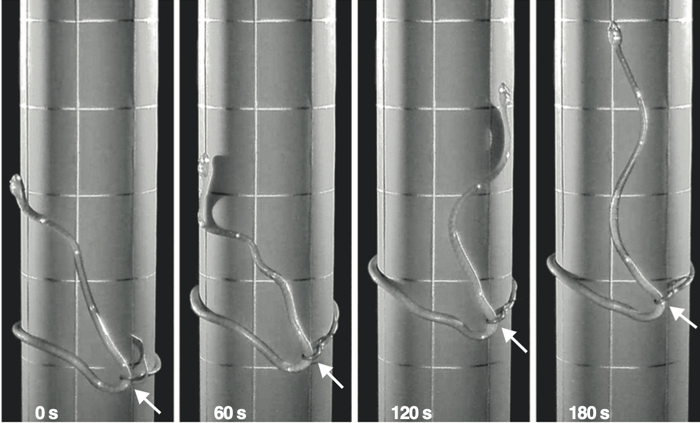

In the observed movement, the snakes climbed smooth, vertical cylinders using the distinct lasso-like body posture, with the head and neck oriented above the posterior body loop that encircles and grips the cylinder.

While the technique enables the brown tree snake to climb cylinders with twice the diameter of other methods, such as concertina movement – which also involves friction gripping, and is used to ascend trees and structures – it's not easy to pull off.

"Slow speeds, slipping, frequent pausing, and heavy breathing during pauses all suggest lasso locomotion is demanding," the researchers write.

"Even though they can climb using this mode, it is pushing them to the limits," says biologist Bruce Jayne from the University of Cincinnati. "The snakes pause for prolonged periods to rest."

(Cell Press/YouTube)

NATURE

PETER DOCKRILL

11 JANUARY 2021

Scientists have identified an entirely new mode of snake locomotion. The newly documented climbing behaviour is difficult, but allows snakes to impressively shimmy up large, smooth cylinders.

Researchers have dubbed it 'lasso locomotion', because the snake climbs poles by lassoing its body around the cylindrical structures, gripping them tightly in a looped noose from torso to tail.

The phenomenon, which expands the known climbing repertoire of snakes, seems to let the brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis) ascend much larger smooth cylinders than any previously known climbing behaviour – and may constitute the first entirely new form of snake movement identified in recent history.

"For nearly 100 years, all snake locomotion has been traditionally categorised into four modes: rectilinear, lateral undulation, sidewinding, and concertina," a research team led by conservation biologist Julie Savidge from Colorado State University explains in the new paper.

(Savidge et al., Current Biology, 2020)

Another kind of snake movement, slide-pushing, is also recognised by some in the scientific community as a distinct form of locomotion, and occurs on flat surfaces. At the same time, some have suggested existing categorisations should be more diverse than previously acknowledged.

In any case, lasso locomotion is quite different to all of the recognised forms of snake motion, and was a chance discovery made during a conservation project in Guam, where the brown tree snake – an invasive species accidentally introduced into the US island territory in the mid 20th century – has devastated local bird populations (and more besides).

While reviewing video footage of experimental metal baffle structures – designed to protect birds by preventing snakes from reaching sheltered bird boxes – the team noticed something unique.

"We had watched about four hours of video and then all of a sudden, we saw this snake form what looked like a lasso around the cylinder and wiggle its body up," wilderness medicine researcher Thomas Seibert explains.

"We watched that part of the video about 15 times. It was a shocker. Nothing I'd ever seen compares to it."

In the observed movement, the snakes climbed smooth, vertical cylinders using the distinct lasso-like body posture, with the head and neck oriented above the posterior body loop that encircles and grips the cylinder.

While the technique enables the brown tree snake to climb cylinders with twice the diameter of other methods, such as concertina movement – which also involves friction gripping, and is used to ascend trees and structures – it's not easy to pull off.

"Slow speeds, slipping, frequent pausing, and heavy breathing during pauses all suggest lasso locomotion is demanding," the researchers write.

"Even though they can climb using this mode, it is pushing them to the limits," says biologist Bruce Jayne from the University of Cincinnati. "The snakes pause for prolonged periods to rest."

(Thomas Seibert)

Now that we know about lasso locomotion, though, the researchers are hoping to make the effort even more challenging for the snakes, with new kinds of barriers and obstructions specifically designed to counter this unexpected form of vertical movement.

That might sound unkind, but it's all to give Guam's declining bird populations - along with other members of the ecosystem that rely on them - a hope of survival in the face of a deadly threat that can slither in ways we never even knew about.

"Most of the native forest birds are gone on Guam," says Savidge.

"Hopefully what we found will help to restore starlings and other endangered birds, since we can now potentially design baffles that the snakes can't defeat. It's still a pretty complex problem."

The findings are reported in Current Biology.

Now that we know about lasso locomotion, though, the researchers are hoping to make the effort even more challenging for the snakes, with new kinds of barriers and obstructions specifically designed to counter this unexpected form of vertical movement.

That might sound unkind, but it's all to give Guam's declining bird populations - along with other members of the ecosystem that rely on them - a hope of survival in the face of a deadly threat that can slither in ways we never even knew about.

"Most of the native forest birds are gone on Guam," says Savidge.

"Hopefully what we found will help to restore starlings and other endangered birds, since we can now potentially design baffles that the snakes can't defeat. It's still a pretty complex problem."

The findings are reported in Current Biology.

No comments:

Post a Comment