The Most Overlooked Energy Source On Earth

About a month ago, a report by clean energy watchdog Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) confirmed that the renewable energy sector has remained the most resilient to the ravages of Covid-19, with global energy transition investments in 2020 clocking in at a record $501.3 billion, good for 9% Y/Y growth. As expected, solar, wind power, and EVs commanded the lion’s share of clean energy investments, while investments in hydrogen tech and carbon capture and storage (CCS) managed to reach a combined $4.5B.

Unfortunately, one renewable energy source has continued to be conspicuous by its absence: Tidal and wave power.

But make no mistake about it: BNEF has warned that the world could be unable to reach its climate goals in the stipulated time to avoid catastrophic climate change if it continues to ignore fringe technologies such as CCS and hydrogen. You can add ocean power to that list.

IRENA has estimated the wave energy potential at around 29,500 TWh per year, meaning ocean power alone could theoretically meet the energy needs of the entire globe.

However, this could be the tipping point when tidal and wave power finally go mainstream and even begins to rival conventional renewables such as solar and wind.

Blue energy explosion

The EU has acknowledged that blue energy is destined to play a much bigger role in our energy mix as the world transitions to clean energy.

While still focusing chiefly on wind power, the commission’s upcoming offshore energy strategy will seek to boost other ocean energy sources, including wave and tidal, according to a draft policy document. The objective is for offshore wind to reach installed capacities of 60 gigawatts (GW) by 2030 and 1-3 GW for ocean energy by a similar date. That will pave the way for a much bigger buildout of 300 and 60 GW, for offshore wind and ocean power, respectively, by 2050.

Just how ambitious is that goal?

Well, the commission points out that aiming for 60 GW of ocean energy by 2050 will mean a massive ramp-up of the technology at a speed that has no equivalent in any other energy technologies in the past.

Related Video: Four of the Coolest Fictional Power Sources

Currently, there are 13 MW of ocean power facilities being tested in EU waters, with tidal considered closest to commercialization while wave energy technologies are mostly still at the R&D stage.

And a lot more money will have to flow into the sector for that ambitious goal to be met. Wave and tidal technologies in Europe have only managed to attract a total of €3.84 billion in research funds between 2007 and 2019, with the majority (€2.74 billion) coming from private sources.

Riding the Tidal Wave

The EU is in good company.

The Ocean Energy Systems (OES), an offshoot of the International Energy Agency, has been working round the clock to pool all the research it can in a bid to achieve large-scale ocean power deployment in the near future.

The 24-member OES, including the United States, China, most E.U. nations, and India, believes ocean power has the potential to become the Holy Grail of renewable energy due to its sheer potential.

The OES has identified several challenges centered around affordability, reliability, operability, installability, standardization, funding availability, and capacity building that will require to be solved before ocean power can become a mainstream renewable energy source.

The organization, in particular, emphasizes the need for significant cost reductions required for ocean energy technologies to compete successfully with other low-carbon technologies. The European target is to get tidal stream energy down to €0.10 per kilowatt-hour and wave power down to €0.15 by 2030, which would also make them competitive with fossil fuels if these traditional sources were obliged to pay for capture and storage of the carbon dioxide they generate

Ocean power benefits

Ocean power comes with some distinct advantages.

First off, it’s clean and compact, featuring higher energy density than either solar and wind projects. For instance, Sihwa Lake Tidal Power Station in South Korea, the world’s largest tidal project with an installed capacity of 254MW, was easily added to a 12.5km-long seawall that was built in 1994 to protect the coast against flooding. Compare that to the 781.5MW Roscoe wind farm in Texas, which takes up 400km2 of farmland, or the 150MW-Fowler Ridge wind project in Indiana that sits on a 202.3km2 parcel of land.Related: Iran’s Geopolitical Powerplay Continues With Iraqi Oil Deals

Even solar farms are usually bigger, such as the Bhadla Industrial Solar Park in Rajasthan, India, that is spread across 45km2 of land or the Tengger Desert Solar Park in China that covers 43km2. This means that even smaller countries with long enough stretches of coastline can use tidal power to compete with bigger, land-rich countries such as the United States, China, and India that can afford to dedicate large tracts of land for solar and wind projects.

Unfortunately, only Scotland currently generates any meaningful amounts of ocean power.

Scotland has enormous natural potential thanks to its impressive archipelago of islands with heavy tidal currents that can be easily tapped. Located in the Northern territory of the U.K., the nation now boasts the largest tidal array of underwater turbines in the world. Scotland’s tidal turbines have even exceeded expectations, with the MeyGen company now planning to vastly increase the number of installations.

Other leading countries developing ocean power technologies are Canada and the United Kingdom, both endowed with some of the highest tides anywhere in the world. Canada has a number of tidal energy schemes along its Atlantic coast, primarily in Nova Scotia, where scores of competing companies are testing various prototypes. The U.K. has more than 20 of these projects in the pipeline, some still in the research and development stage, but many in the process of being scaled up for deployment.

Meanwhile, China encourages tidal stream energy by offering a generous feed-in tariff 3x the price of fossil fuels. That’s similar to the rate deployed by countries that are trying to launch solar and wind power. The incentive is high enough that one Chinese company is already feeding ocean power into the main grid profitably.

As for the United States, the EIA says that the country lacks an abundance of suitable sites to harness ocean power and will have to be content with other low-carbon technologies such as solar, wind, and biofuels, where it has better competitive advantage.

By Alex Kimani for Oilprice.com

Nova Scotia's first in-stream tidal turbine starts producing power

Left: An illustration of Cape Sharp Tidal's in-stream tidal turbine, which was deployed in the Bay of Fundy on Nov. 7 and was connected to the grid today. Right: Map showing location of the Fundy Ocean Research Centre (FORCE). (Illustration: Tyana Awada/Canadian Geographic; Map: ©2016 Google)

By Michela Rosano

November 22, 2016

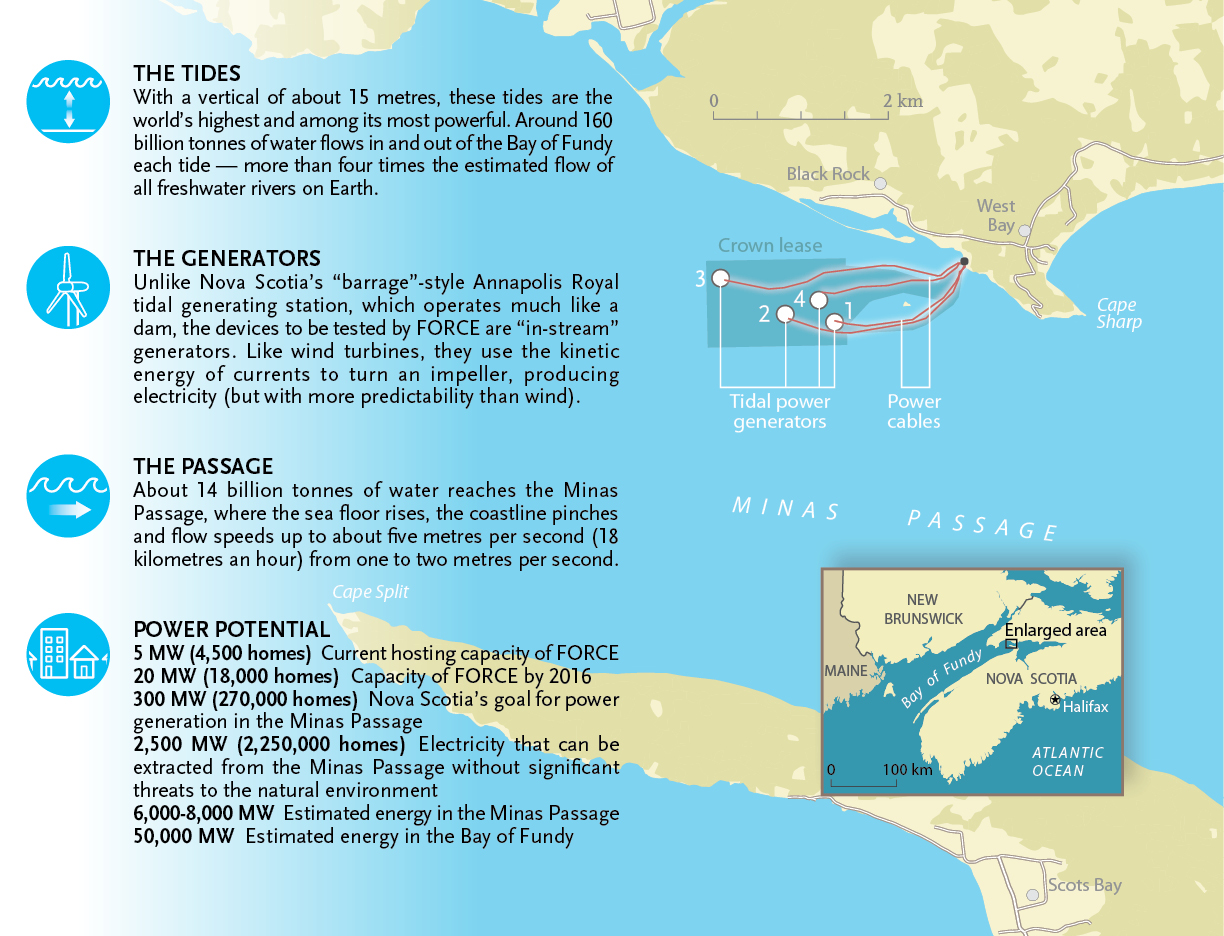

Nova Scotians are about to receive a flicker of power from North America's first in-stream tidal turbine. On Nov. 7 Cape Sharp Tidal, a partnership between Emera and OpenHydro/DCNS, deployed the first of two 1,000-tonne two-megawatt turbines at the Fundy Ocean Research Centre (FORCE) in the Bay of Fundy’s Minas Passage and today, it was connected to Nova Scotia Power’s transmission system. The turbine will help power 500 homes.

A second 16-metre turbine will be lowered into the surging tides in 2017 and complete the first phase of a commercial-scale tidal energy project at FORCE, which aims to produce up to 300MW of power in the 2020s.

FORCE is a non-profit organization that provides a testing site for tidal technology in four underwater, 200-metre-wide berths (the only sea floor in Fundy with a Crown lease for energy development), and doubles as a research institute with an environmental watchdog mandate.

These infographics, adapted from a larger piece that appeared in Canadian Geographic’s July/August 2015 issue, depict the four tidal-power prototypes (including the Cape Sharp Tidal turbine) that had been signed up for testing at FORCE at the time of the magazine's publication, and where they were set to be deployed.

(Illustrations: Tyana Awada/Canadian Geographic; Maps: Chris Brackley/Canadian Geographic)

No comments:

Post a Comment