Author of the article: Hamdi Issawi

Publishing date: Oct 02, 2021

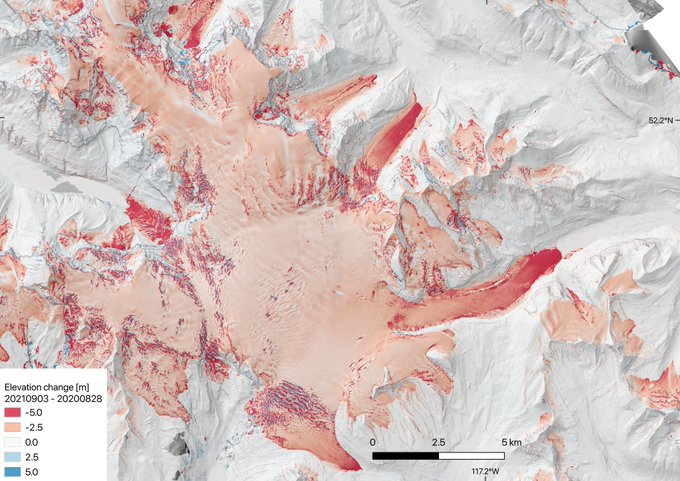

An aerial view of elevation change of the Columbia Icefields revealed by laser altimetry. The deep red grooves on the right indicate the thinning termini of the Athabasca, top, and Saskatchewan, bottom, glaciers

The province is long past the oppressive “heat dome” that caused cities to swelter last summer, but warmer temperatures this year had a lasting effect on the glacier that feeds Edmonton’s water supply.

The Saskatchewan Glacier terminus saw 10 metres of thinning this year, said Brian Menounos, an earth sciences professor at the University of Northern British Columbia and Canada Research Chair in glacier change. It’s also the glacier that feeds the North Saskatchewan River, Edmonton’s sole source of drinking water.

“We’ve known for a number of years that — largely due to greenhouse gas emissions — we have accelerated the melt of the cryosphere,” he said, referring to the part of the planet covered in ice or snow. “It’s a symptom of a larger problem in that it was an exceptionally bad year for the glaciers by and large.”

In a social media post, Menounos shared an image of the Columbia Icefield that shows a change in elevation over the past year measured by laser altimetry. The technology uses an aircraft to bounce laser light off the surface of the ice field about once a year. The time it takes for light to reflect back to the aircraft and trip a sensor allows scientists to measure the change in surface elevation.

The province is long past the oppressive “heat dome” that caused cities to swelter last summer, but warmer temperatures this year had a lasting effect on the glacier that feeds Edmonton’s water supply.

The Saskatchewan Glacier terminus saw 10 metres of thinning this year, said Brian Menounos, an earth sciences professor at the University of Northern British Columbia and Canada Research Chair in glacier change. It’s also the glacier that feeds the North Saskatchewan River, Edmonton’s sole source of drinking water.

“We’ve known for a number of years that — largely due to greenhouse gas emissions — we have accelerated the melt of the cryosphere,” he said, referring to the part of the planet covered in ice or snow. “It’s a symptom of a larger problem in that it was an exceptionally bad year for the glaciers by and large.”

In a social media post, Menounos shared an image of the Columbia Icefield that shows a change in elevation over the past year measured by laser altimetry. The technology uses an aircraft to bounce laser light off the surface of the ice field about once a year. The time it takes for light to reflect back to the aircraft and trip a sensor allows scientists to measure the change in surface elevation.

1/3 Gigaton of mass loss from Columbia Icefield revealed by our 2021 ACO survey. Saskatchewan Glacier (SW) terminus thinned by 10 m! Combined effect of #heatdome, #bcwildfire s and ongoing #ClimateCrisis

Sparse blue spots on the image show areas of increased elevation — where the ice field gained mass — while the overwhelming red area indicates a decrease in elevation due to melting. The greatest decreases can be seen at the termini of the Athabasca and Saskatchewan glaciers, both of which bear the resemblance of deep red tongues lapping out north and east.

“We find pretty much wholesale thinning throughout all elevation bands on the ice field, and that is something that we’ve not seen to date,” he added, noting that while scientists have been monitoring the glaciers for years, they only started using laser altimetry in the ice field since 2017.

Glaciers are an important source of fresh water, particularly in Western Canada. A paper co-authored by Menounos found that the world’s glaciers are now losing 267 billion tonnes of ice every year (one billion tonnes of ice is equal in mass to 10,000 fully loaded aircraft carriers). It also cited research suggesting that more than one billion people worldwide could face water shortages by 2050.

“Anytime you’re talking about a freshwater resource that Canadians rely on — snow and ice collectively — it is a cause for concern,” Menounos said.

Matthew Chernos, a Calgary-based hydrologist and consultant, said the high alpine glaciers feeding Alberta’s river systems act as natural reservoirs. While the North Saskatchewan River is mostly made up of rainwater and snow melt by the time it reaches Edmonton, he said, glacier melt is a big part of the river flow in July and August, when the glacier’s winter snow pack has melted away.

And as Alberta gets warmer, Chernos added, more of that snow pack will melt earlier, increasing the length of the low flow season and the amount of melting glacier ice, a non-renewable resource.

“The only way to offset that would be more rainfall, and that’s also not something that’s predicted to happen in the future,” he said. “In fact, most of Alberta is expected to be even drier in the summers.”

The scientists were quick to note that fading glaciers also threaten sensitive aquatic ecosystems that rely on cooler water to stay healthy, and the irrigation demands of the agriculture industry.

Menounos isn’t optimistic about better weather conditions correcting the problem either.

“Over the last 30 to 50 years of monitoring these glaciers, the odd-ball positive year, where the snow was plenty, is not compensating for the continued melt that we’re getting each year,” he said.

“It’s kind of a losing battle.”

– With files from The Canadian Press

“We find pretty much wholesale thinning throughout all elevation bands on the ice field, and that is something that we’ve not seen to date,” he added, noting that while scientists have been monitoring the glaciers for years, they only started using laser altimetry in the ice field since 2017.

Glaciers are an important source of fresh water, particularly in Western Canada. A paper co-authored by Menounos found that the world’s glaciers are now losing 267 billion tonnes of ice every year (one billion tonnes of ice is equal in mass to 10,000 fully loaded aircraft carriers). It also cited research suggesting that more than one billion people worldwide could face water shortages by 2050.

“Anytime you’re talking about a freshwater resource that Canadians rely on — snow and ice collectively — it is a cause for concern,” Menounos said.

Matthew Chernos, a Calgary-based hydrologist and consultant, said the high alpine glaciers feeding Alberta’s river systems act as natural reservoirs. While the North Saskatchewan River is mostly made up of rainwater and snow melt by the time it reaches Edmonton, he said, glacier melt is a big part of the river flow in July and August, when the glacier’s winter snow pack has melted away.

And as Alberta gets warmer, Chernos added, more of that snow pack will melt earlier, increasing the length of the low flow season and the amount of melting glacier ice, a non-renewable resource.

“The only way to offset that would be more rainfall, and that’s also not something that’s predicted to happen in the future,” he said. “In fact, most of Alberta is expected to be even drier in the summers.”

The scientists were quick to note that fading glaciers also threaten sensitive aquatic ecosystems that rely on cooler water to stay healthy, and the irrigation demands of the agriculture industry.

Menounos isn’t optimistic about better weather conditions correcting the problem either.

“Over the last 30 to 50 years of monitoring these glaciers, the odd-ball positive year, where the snow was plenty, is not compensating for the continued melt that we’re getting each year,” he said.

“It’s kind of a losing battle.”

– With files from The Canadian Press

No comments:

Post a Comment