Krishnagopal Mallick’s Bengali queer writing | The maze runner

Krishnagopal Mallick’s writing finds a new lease of life in translation

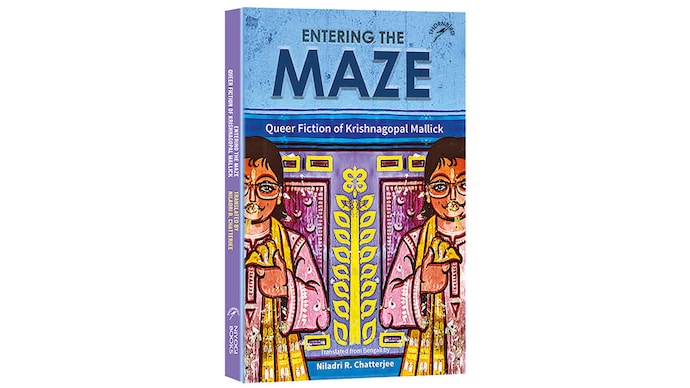

Until now, the world has known little about Krishnagopal Mallick (1936-2003). But a recent collection of his Bengali queer writing, translated by Niladri R. Chatterjee, Entering the Maze: Queer Fiction of Krishnagopal Mallick, excavates Mallick from what Chatterjee calls the “dust of homophobic neglect”.

Mallick’s irreverent text shatters prim notions of bourgeois sexual morality. While it is undoubtedly queer, saturated with Mallick’s homoerotic gaze, it is also much more: spatial ethnography, critique of public policy, bildungsroman, memoir, and love letter to College Square (in Kolkata).

Chatterjee writes admiringly of Mallick’s candour about being a “confirmed homosexual” while leading a traditional family life. Ruth Vanita’s blurb refers to the “charming insouciance” of the writing. But a different reading reveals a certain breathlessness woven into the text. The collection consists of two short stories, The Difficult Path and Senior Citizen, as well as the novella Entering the Maze, a memoir of his teenage years, in which we encounter narrative accounts of Kolkata during pivotal historical moments: World War II bombings, the bloodbath of rioting Hindus and Muslims, the changing cartography of the Indian subcontinent through iterative partitions, and so on. We read descriptions of the geography and milieu he spent his boyhood in: house, neighbourhood, public transportation (trams, double-decker buses, trains).

We also find descriptions of Mallick’s sexual awakening: early experiences of masturbation, sexual encounters with older men that border on sexual assault but are never unambiguously that, and an intense sexual tryst with Manoj, a fellow ninth grader. There is something magical about the intensity of the latter sexual experience, but the reader nevertheless feels that the consummation of the attraction does not fully extinguish the longing Mallick feels for Manoj.

In the two short stories, we note some similar themes, detailed accounts of the cityscape, the nonconsensual groping of younger men’s genitals on crowded public transportation, and so on. But in both of these narratives, desire is imbricated with danger, and rendered more complex by Mallick’s self-awareness of the difference in age between himself and the men/boys he desires (he is an older man in the two texts). This is made particularly harrowing by the fact that the bureaucratic category of the ‘Senior Citizen’ grants those labelled as such certain privileges but also makes them endure specific indignities.

Chatterjee’s translation is very effective, but perhaps most notably so for those who are Bengali-speaking and already familiar with Kolkata. After all, there is only so much a translator can do when the text presumes a certain contextual literacy as it refers to things like the Thanthané Kali temple tram stop, hilsa from Canning, Hajabarala (1921). But Chatterjee’s greatest accomplishment here is that he has dusted off quite a bit of “homophobic neglect” and, consequently, made the world a richer place.

No comments:

Post a Comment