Fossils and modern experiments are telling us what a shark's nose knows.

JEANNE TIMMONS - 7/6/2023

Enlarge / Artist's reconstruction of the shark as it once lived.

Klug et. al.24WITH

Sharks are largely cartilaginous, a body structure that often doesn’t survive fossilization. But in a paper published in the Swiss Journal of Paleontology, scientists describe an entirely new species of primitive shark from the Late Devonian period, a time when they were just beginning to proliferate in ancient oceans.

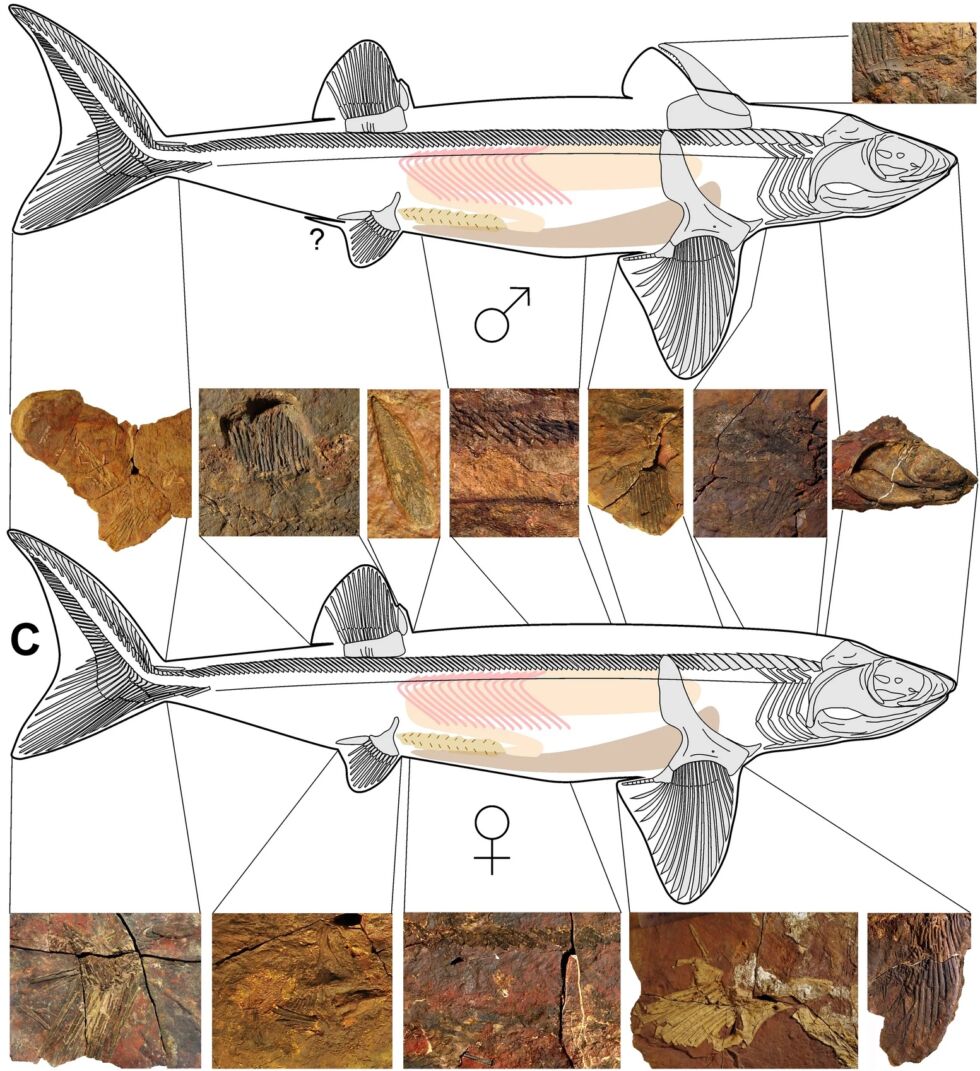

The team found several exceptionally well-preserved fossils that include soft tissues such as scales, musculature, digestive tract, liver, and blood vessel imprints. Also preserved: the species’ most distinct feature, widely separated nasal organs, somewhat akin to those on today’s hammerhead sharks. The find suggests that sharks’ finely tuned sense of smell, the subject of urban legends, was already being selected for just as these predators were becoming established.

A key time and a rare find

Christian Klug is the lead author and curator of the Paleontological Institute and Museum at Zurich University. He explained the significance of the Devonian period in the oceans’ history, when life was flourishing and an evolutionary arms race was in full swing. “With increasing competition among predators inhabiting the water column, the entire organism was selected for more efficiency,” he explained. “This affected swimming abilities, feeding apparatus, but also the sensory systems, which are essential to detect prey, to orient themselves in space, and to escape from even larger predators such as the huge placoderm Dunkleosteus and the equally large shark Ctenacanthus.”

That placoderm was arguably one of the most terrifying fish of the Devonian, as Dunkleosteus was an armor-plated tank with razor-sharp fangs and a deadly bite force.

Enlarge / Dunkleosteus. When you're sharing the oceans with these beasts, you can bet there's a lot of evolutionary competition.

Wikimedia Commons

The new fossils come from the Maïder and Tafilalt regions of the eastern Anti-Atlas of Morocco, a country with incredibly rich fossil deposits. Wahiba Bel Haouz is a co-author and geologist at the Faculty of Sciences, University of Hassan II Casablanca. She described a number of Moroccan locations “famous among fossil collectors,” including “the fossiliferous Devonian to Lower Carboniferous strata. Ammonoids, trilobites, brachiopods, fishes, corals, and trace fossils are locally so abundant that specific fossil beds have been mined over many kilometers, leaving marker trenches in the desert. Cephalopods are so abundant at many levels, even after decades of heavy commercial exploitation, that it is justified to call the region a ‘cephalopod paradise.’”Advertisement

The new shark fossils were found in deposits filled with fossil mollusks, crustaceans, armored fish (placoderms), cartilaginous fish (acanthodian stem-chondrichthyans), and bony fish (actinopterygians and sarcopterygians). Unlike other fish found at this time and from most other localities, the fossils at this site weren’t flattened by millions of years of geologic pressure.

The team named this new shark species Maghriboselache mohamezanei, a nod to the country where it was found and one of the people responsible for finding it. (The phrase “al Maghrib” is Arabic meaning “Morocco”; “selachos” is Greek for “cartilaginous fish”; and “mohamezanei” is in honor of Moha Mezane, a self-taught geologist who not only found a number of the specimens described in this paper, but other important fossil discoveries as well.)

The exceptional preservation, combined with a CT scanner, provided an exceedingly rare three-dimensional skull that offered scientists a view into the neurocranium of a fish that lived approximately 350 to 383 million years ago. They were surprised to discover that it had widely spaced nasal capsules (the nostrils and the internal tube connected to it).

The smell of the ocean

These nasal capsules are “really surprising and exciting,” said Abdelouahed Lagnaoui, the co-author of this paper and professor of stratigraphy and paleontology at the Ecole Supérieur de l’Education et de la Formation, Université Hassan Premier de Berrechid. This, he said, “is an unknown feature in other contemporary or subsequent Palaeozoic sharks and might even be the earliest instance in all jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes).”

Most sharks, even today, have nasal capsules spaced closely together. One significant exception is the hammerhead, whose cephalofoil—the flattened, hammer-shaped head—contains a nasal capsule on either side.

We are still learning about olfactory capabilities in extant sharks, but one hypothesis proposes that having nasal capsules spaced widely apart enables a shark to pinpoint odors with more precision. The spacing is thought to enable it to determine which side a smell is stronger on, allowing the fish to turn toward it. This is otherwise known as the ability to smell in stereo, a capability, the team suggests, that Maghriboselache may have had, even if the nasal capsules were not as far apart as today’s hammerheads.

Finding a fossil such as Maghriboselache “helps us get to the question of form and function,” Aubrey Clark, a sensory biologist and PhD student at Florida Atlantic University, said. “Because in a fossil, you see form, but you may not necessarily know the function.”

The scent of the modern

To understand what the features of Maghriboselache might be telling us, we need to get at function, which means we have to look to today’s sharks. Lauren Simonitis is a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Biology at Florida Atlantic University and University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Labs. Her research focuses on shark nose structure, how that impacts water flow through the nose, and how that water flow might affect their olfactory sensitivity. “There are so many different types of sharks,” Simonitis explained, noting that there is a diversity of shark body shapes, nose structures, and habitats.

Enlarge / Large portions of what appear to be both male and female sharks were preserved.

Klug, et. al.

Clark pointed to work done by one of their advisors, Dr. Tricia Meredith, the research director for Florida Atlantic University’s lab, A.D. Henderson University School, and FAU High School. Clark said that Meredith showed that, while sharks’ olfactory organs come in various sizes, “there’s no real difference in sensitivity between big or small organs, so we’re trying to further investigate reasons for that variation and [water] flow. We’re thinking that flow is a big component of why there are variations and how that is affecting odor detection.”

Simonitis and Clark referenced research by Stephen Kajiura, who noted “the difference between these hammerheads with these really widely spaced nares versus our more typical pointed-headed sharks, where their nares are nice and close to each other.” His work shows “there’s not really a difference in sensitivity that we can measure, but what we can say [is that there is] a difference is their ability to localize those smells. That may be improved because they’re so far apart that you can resolve that odor gradient a little bit more.”

Overcoming myths

As scientists grapple with shark olfactory function from the past and the present, Clark noted that they consistently run into a number of misconceptions perpetuated by films. Painting sharks as voracious “monsters” with a preference for human flesh might make exciting movie plots, she said, but these fish are neither.Advertisement

Oddly, one of the biggest misconceptions is about the sharks’ sense of smell. It’s often claimed that sharks are “super-smellers”—they can detect any amount of blood from any distance. But research by Meredith and others indicates that shark “[odor] sensitivity is similar to [that of] other bony fish. So they’re not really super-smellers. They’re good at smelling, but it’s nothing like popular media likes to say that they are,” Clark stated.

Another misconception, Simonitis added, is the idea that the smell of blood is an instant draw to all sharks at all times and will send them into a feeding frenzy. It may be a draw to some sharks, but not all. In other words, sharks are not mindless eating machines purely motivated by the scent of blood in the water.

She illustrated this by noting if we’re hungry and we smell food from a restaurant, we might be more inclined to stop and get something to eat. If we’re not hungry, we’ll simply drive past. The same holds true for sharks. And whether sharks are interested in a potential meal also depends upon whether a shark has “less access to a consistent food supply,” as well as whether they live in an area with increased competition from other sharks. “There’s a lot of outside factors that go into making that decision to eat,” Simonitis explained, “or making that decision to follow your nose.”

A piece of Morocco

Fossils can help us develop a less-fictional picture of what sharks are capable of. Sharks are “one of our more ancient lineages,” Simonitis noted. That’s “why this paper is so awesome,” as it offers more insight into how and when specializations like olfactory-driven behavior may have evolved.

Simonitis and Clark were enthusiastic about this exquisitely preserved 3D fossil, a rarity from a fish whose morphology doesn’t lend itself to surviving through deep time. Its presence in the rich bed of fossils like those found in Morocco can help us understand the ecological factors that drove that evolution.

Klug emphasized that most of these fossils will remain in their country of origin, saying that Maghriboselache’s “holotype and some of the best skeletons are already back in Morocco.” In a country rich with remarkable fossils, Bel Haouz not only hopes local museums will “exhibit some of [Morocco’s] famous fossils” but also that people in Morocco will learn “more about the important palaeontological richness of this area.”

JEANNE TIMMONS

A renewed interest in paleontology later in life propelled Jeanne to start freelance writing. Her Bachelor's degree from Drew University was not in science, so she’s spent over ten years taking online classes and reading paleontological books and scientific papers. She has also attended annual meetings of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology and the International Conference on Mammoths and Their Relatives, and was a participant in the Valley of the Mastodons conference at California’s Western Science Center. Scientists from all over the globe have been interviewed for her blog (mostlymammoths.wordpress.com). Her work appears in Ars, Gizmodo, and the New York Times. You can find her on Twitter @mostlymammoths.

No comments:

Post a Comment