Ancient metal cauldrons give us clues about what people ate in the Bronze Age

Archaeologists have long been drawing conclusions about how ancient tools were used by the people who crafted them based on written records and context clues. But with dietary practices, they have had to make assumptions about what was eaten and how it was prepared.

A new study published in the journal iScience on August 18 analyzed protein residues from ancient cooking cauldrons and found that the people of Caucasus ate deer, sheep, goats, and members of the cow family during the Maykop period (3700–2900 BCE).

"It's really exciting to get an idea of what people were making in these cauldrons so long ago," says Shevan Wilkin of the University of Zurich. "This is the first evidence we have of preserved proteins of a feast—it's a big cauldron. They were obviously making large meals, not just for individual families."

Scientists have known that the fats preserved in ancient pottery and the proteins from dental calculus—the hard mineralized plaque deposits on the teeth—contain traces of the proteins ancient people consumed during their lives.

Now, this study combines protein analysis with archaeology to explore specific details about the meals cooked in these particular vessels. Many metal alloys have antimicrobial properties, which is why the proteins have been preserved so well on the cauldrons. The microbes in dirt that would normally degrade proteins on surfaces such as ceramic and stone are held at bay on metal alloys.

"We have already established that people at the time most likely drank a soupy beer, but we did not know what was included on the main menu," says Viktor Trifonov of the Institute for the History of Material Culture.

The researchers collected eight residue samples from seven cauldrons that were recovered from burial sites in the Caucasus region. This region sits between the Caspian and Black Seas spanning from Southwestern Russia to Turkey and includes the present-day countries Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia.

They successfully retrieved proteins from blood, muscle tissue, and milk. One of these proteins, heat shock protein beta-1, indicates that the cauldrons were used to cook deer or bovine (cows, yaks, or water buffalo) tissues. Milk proteins from either sheep or goats were also recovered, indicating that the cauldrons were used to prepare dairy.

Radiocarbon dating allowed the researchers to specifically pinpoint that the cauldrons could have been used between 3520–3350 BCE. This means that these vessels are more than 3,000 years older than any vessels that have been analyzed before. "It was a tiny sample of soot from the surface of the cauldron," says Trifonov. "Maykop bronze cauldrons of the fourth millennium BC are a rare and expensive item, a hereditary symbol belonging to the social elite."

Although the cauldrons show signs of wear and tear from use, they also show signs of extensive repair. This suggests that they were valuable, requiring great skill to make and acting as important symbols of wealth or social position.

The researchers would like to explore similarities and differences in the residues from a wider range of vessel types. "We would like to get a better idea of what people across this ancient steppe were doing and how food preparation differed from region to region and throughout time," says Wilkin. Since cuisine is such an important part of culture, studies like this one may also help us to understand the cultural connections between different regions.

The methods used in this study have shown that there is great potential for this new approach. "If proteins are preserved on these vessels, there is a good chance they are preserved on a wide range of other prehistoric metal artifacts," says Wilkin. "We still have a lot to learn, but this opens up the field in a really dramatic way."

More information: Curated cauldrons: Preserved proteins from early copper alloy vessels illuminate feasting practices in the Caucasian steppe, iScience (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.107482

Journal information: iScience

Provided by Cell Press

Yak milk consumption among Mongol Empire elites

Sequencing genes of Iron and Bronze Age peoples to better understand early Mediterranean migration patterns

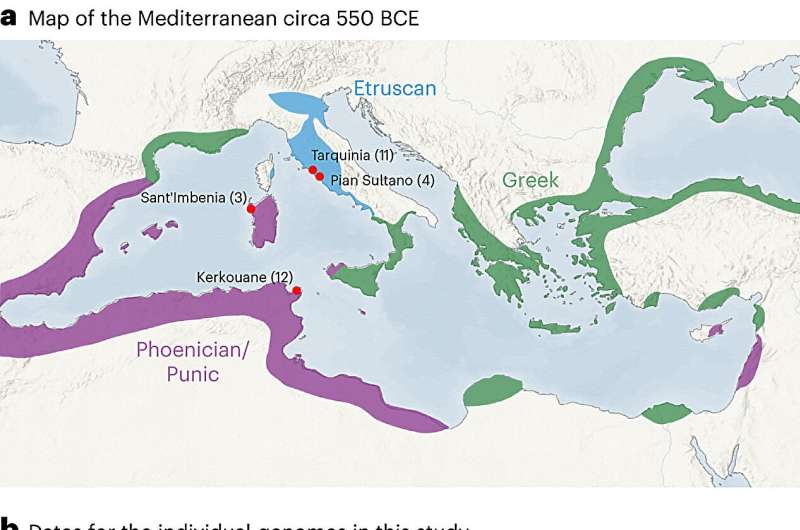

An international team of anthropologists, archaeologists and geneticists has learned more about the migration patterns of people living around the Mediterranean Sea during the Iron and Bronze ages. In their study, reported in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, the group conducted genetic sequencing on the remains of 30 people who lived during the Iron or Bronze Age in Italy, Tunisia and Sardinia.

As the researchers note, most knowledge of people living around the Mediterranean Sea during the Iron and Bronze Ages derives from study of artifacts they left behind. But such evidence, they point out, does not reveal much about the backgrounds of those people or where their ancestors came from. In this new effort, the research team sought to learn more about the backgrounds of such people by following migration patterns using genetic sequencing.

The researchers conducted shotgun sequencing (sequencing conducted in random fashion) on samples collected from unearthed bones of ancient people living in Italy, Tunisia and Sardinia to get a sense of migration patterns for people living in the northern, central and southern parts of the eastern part of the Mediterranean during the Iron and Bronze Ages—a time, the researchers note, when people were traveling greater distances due to advances in boat and shipbuilding. The team then compared their findings to the results of other sequencing efforts conducted on both modern and ancient peoples living in the region.

They found evidence of widespread migration around the Mediterranean, suggesting strong ties between distant people. They also found heterogeneity in Iron Age populations and shifts in ancestry in North Africa and Sardinia during the Bronze Age, suggesting an uptick in migration. More specifically, the research revealed an increase in migration from what is now Morocco and Iran by neolithic farmers to both Sardinia and Tunisia, and somewhat less migration to what is now Italy.

The research team suggests that there was an increase in migration, as expected during both the Iron and Bronze Ages, as people sailed the Mediterranean Sea for a myriad of reasons—and in so doing, shaped the ancestry of those who lived in the region.

More information: Hannah M. Moots et al, A genetic history of continuity and mobility in the Iron Age central Mediterranean, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-023-02143-4. On bioRxiv: www.biorxiv.org/content/10.110 … /2022.03.13.483276v3

No comments:

Post a Comment