Why India is becoming a space force to be reckoned with

Rachyl Jones

Thu, August 24, 2023

INDRANIL MUKHERJEE/AFP via Getty Images

India on Wednesday not only completed its first mission to the moon, 54 years after the U.S. first touched down, but it landed on the moon’s south pole—a feat no other country has been able to accomplish.

The mission’s success comes days after a Russian spacecraft crashed into the lunar south pole. The two countries had been racing to put an unmanned spacecraft in that region after scientists discovered traces of water there. The elements of water—hydrogen and oxygen—are essential components to rocket fuel, so harvesting them on the moon could allow spacecrafts to top off their tanks for further exploration, according to the Institute of Physics. The existence of water on the moon could also help sustain astronauts in space for long periods of time, providing a drinking source and supporting the growth of plants for food, it reported. India placed a rover in the region to collect data on the elemental composition of the soil and rocks, according to the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

“This success belongs to all of humanity,” India’s prime minister Narendra Modi said during a webcast of the event.

The feat by the country of 1.4 billion people comes at a time when private, for-profit companies have stolen the spotlight in space exploration. Elon Musk's Space X has a target of sending humans to Mars (though Musk's timeline is in flux), and NASA is currently completely reliant on SpaceX rockets to get its human crews into space.

India is increasingly becoming a major player in the space world, with this mission cementing its place in history. Previously, the U.S., China and the Soviet Union (now Russia) all landed on the moon, though the U.S. is still the only country to touch down with a crew. The prospect of gaining access to water on the moon means these countries and more will be racing for a slice of the action. A new space race has already begun, and India has more up its sleeve.

The mission has been twenty years in the making. Then-Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, announced his ambitions for India to go to the moon during his Independence Day speech in 2003. Its first mission was five years later, when the ISRO successfully placed a ship in the moon’s orbit for 312 days. It then attempted to land and deploy a rover in 2019, but an error in the software caused the landing spacecraft and rover to crash. The organization improved the tech from its second mission for the Chandrayaan-3—the third and most recent trip—including adding stronger legs on the landing machine, removing an engine and lengthening the energy-supplying solar panels, according to the Times of India. The country also became the first to enter Mars’ orbit on the first try in 2014.

The ISRO’s future space plans largely revolve around the moon—literally. It is preparing a joint flight with Japan, where India will supply the landing machine. The two countries first agreed to work together in 2017. Japan will provide the unmanned launch spacecraft and the rover, which will explore the moon’s south pole. There is no set date for launch.

India also wants to send a manned spacecraft to the moon. The ship, which can hold three passengers, was originally planned to launch in 2021, but delays have pushed that date. Jitendra Singh, India’s Union Minister of State for science and technology, wants it to take off in 2024, but he plans to send two unmanned spaceships first to test for safety, the Economic Times reported. A successful landing with passengers would make India second only to the U.S. to complete such an operation.

Even as India sends its tricolor flag to remote extra-terrestrial locations, a thriving private space industry is also taking root within the country. According to a recent New York Times article, there are at least 140 registered space startups in India. And while the ISRO budget was less than $1.5 billion in the past fiscal year, the private space sector is currently worth more than $6 billion, according to the report.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Rachyl Jones

Thu, August 24, 2023

INDRANIL MUKHERJEE/AFP via Getty Images

India on Wednesday not only completed its first mission to the moon, 54 years after the U.S. first touched down, but it landed on the moon’s south pole—a feat no other country has been able to accomplish.

The mission’s success comes days after a Russian spacecraft crashed into the lunar south pole. The two countries had been racing to put an unmanned spacecraft in that region after scientists discovered traces of water there. The elements of water—hydrogen and oxygen—are essential components to rocket fuel, so harvesting them on the moon could allow spacecrafts to top off their tanks for further exploration, according to the Institute of Physics. The existence of water on the moon could also help sustain astronauts in space for long periods of time, providing a drinking source and supporting the growth of plants for food, it reported. India placed a rover in the region to collect data on the elemental composition of the soil and rocks, according to the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

“This success belongs to all of humanity,” India’s prime minister Narendra Modi said during a webcast of the event.

The feat by the country of 1.4 billion people comes at a time when private, for-profit companies have stolen the spotlight in space exploration. Elon Musk's Space X has a target of sending humans to Mars (though Musk's timeline is in flux), and NASA is currently completely reliant on SpaceX rockets to get its human crews into space.

India is increasingly becoming a major player in the space world, with this mission cementing its place in history. Previously, the U.S., China and the Soviet Union (now Russia) all landed on the moon, though the U.S. is still the only country to touch down with a crew. The prospect of gaining access to water on the moon means these countries and more will be racing for a slice of the action. A new space race has already begun, and India has more up its sleeve.

The mission has been twenty years in the making. Then-Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, announced his ambitions for India to go to the moon during his Independence Day speech in 2003. Its first mission was five years later, when the ISRO successfully placed a ship in the moon’s orbit for 312 days. It then attempted to land and deploy a rover in 2019, but an error in the software caused the landing spacecraft and rover to crash. The organization improved the tech from its second mission for the Chandrayaan-3—the third and most recent trip—including adding stronger legs on the landing machine, removing an engine and lengthening the energy-supplying solar panels, according to the Times of India. The country also became the first to enter Mars’ orbit on the first try in 2014.

The ISRO’s future space plans largely revolve around the moon—literally. It is preparing a joint flight with Japan, where India will supply the landing machine. The two countries first agreed to work together in 2017. Japan will provide the unmanned launch spacecraft and the rover, which will explore the moon’s south pole. There is no set date for launch.

India also wants to send a manned spacecraft to the moon. The ship, which can hold three passengers, was originally planned to launch in 2021, but delays have pushed that date. Jitendra Singh, India’s Union Minister of State for science and technology, wants it to take off in 2024, but he plans to send two unmanned spaceships first to test for safety, the Economic Times reported. A successful landing with passengers would make India second only to the U.S. to complete such an operation.

Even as India sends its tricolor flag to remote extra-terrestrial locations, a thriving private space industry is also taking root within the country. According to a recent New York Times article, there are at least 140 registered space startups in India. And while the ISRO budget was less than $1.5 billion in the past fiscal year, the private space sector is currently worth more than $6 billion, according to the report.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Opinion

India's moon landing advances science, the global community

Mariel Borowitz, Georgia Institute of Technology

Fri, August 25, 2023

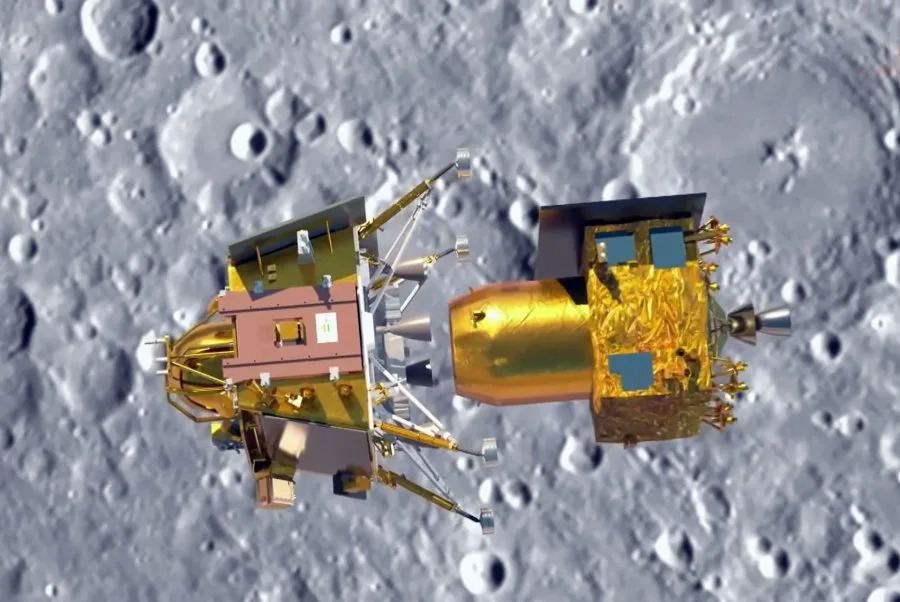

A simulated image is played on screen during live telecast of the landing of Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft on the south pole of the Moon at the ISRO Telemetry Tracking and Command Network (ISTRAC) center in Bengaluru on Wednesday. India became the first nation to land on the south pole region of the moon. Photo courtesy of Indian Space Research Organization

Aug. 25 (UPI) -- India made history as the first country to land near the south pole of the Moon with its Chandrayaan-3 lander on Wednesday. This also makes it the first country to land on the Moon since China in 2020.

India is one of several countries -- including the U.S. with its Artemis program -- endeavoring to land on the Moon. The south pole of the Moon is of particular interest, as its surface, marked by craters, trenches and pockets of ancient ice, hasn't been visited until now.

The Conversation U.S. asked international affairs expert Mariel Borowitz about this moon landing's implications for both science and the global community.

Why are countries like India looking to go to the Moon?

Countries are interested in going to the Moon because it can inspire people, test the limits of human technical capabilities and allow us to discover more about our solar system.

The Moon has a historical and cultural significance that really seems to resonate with people -- anyone in the world can look up at the night sky, see the Moon and understand how amazing it is that a spacecraft built by humans is roaming around the surface.

The Moon also presents a unique opportunity to engage in both international cooperation and competition in a peaceful, but highly visible, way.

The fact that so many nations - the United States, Russia, China, India, Israel - and even commercial entities are interested in landing on the Moon means that there are many opportunities to forge new partnerships.

These partnerships can allow nations to do more in space by pooling resources, and they encourage more peaceful cooperation here on Earth by connecting individual researchers and organizations.

There are some people who also believe that exploration of the Moon can provide economic benefits. In the near term, this might include the emergence of startup companies working on space technology and contributing to these missions. India has seen a surge in space startups recently.

Eventually, the Moon may provide economic benefits based on the natural resources that can be found there, such as water, helium-3 and rare Earth elements.

Are we seeing new global interest in space?

Over the last few decades, we've seen a significant increase in the number of nations involved in space activity. This is very apparent when it comes to satellites that collect imagery or data about the Earth, for example. More than 60 nations have been involved in these types of satellite missions. Now we're seeing this trend expand to space exploration, and particularly the Moon.

In some ways, the interest in the Moon is driven by similar goals as in the first space race in the 1960s -- demonstrating technological capabilities and inspiring young people and the general public. However, this time it's not just two superpowers competing in a race. Now we have many participants, and while there is still a competitive element, there is also an opportunity for cooperation and forging new international partnerships to explore space.

Also, with all these new actors and the technical advances of the last 60 years, there is the potential to engage in more sustainable exploration. This could include building Moon bases, developing ways to use lunar resources and eventually engaging in economic activities on the Moon based on natural resources or tourism.

How does India's mission compare with Moon missions in other countries?

India's accomplishment is the first of its kind and very exciting, but it's worth noting that it's one of seven missions currently operating on and around the Moon.

In addition to India's Chandrayaan-3 rover near the south pole, there is also South Korea's Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter, which is studying the Moon's surface to identify future landing sites; the NASA-funded CAPSTONE spacecraft, which was developed by a space startup company; and NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. The CAPSTONE craft is studying the stability of a unique orbit around the Moon, and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter is collecting data about the Moon and mapping sites for future missions.

Also, while India's Chandrayaan-2 rover crashed, the accompanying orbiter is still operational. China's Chang'e-4 and Chang'e-5 landers are still operating on the Moon as well.

Other nations and commercial entities are working to join in. Russia's Luna-25 mission crashed into the Moon three days before the Chandrayaan-3 landed, but the fact that Russia developed the rover and got so close is still a significant achievement.

The same could be said for the lunar lander built by the private Japanese space company ispace. The lander crashed into the Moon in April 2023.

Why choose to explore the south pole of the Moon?

The south pole of the Moon is the area where nations are focused for future exploration. All of NASA's 13 candidate landing locations for the Artemis program are located near the south pole.

This area offers the greatest potential to find water ice, which could be used to support astronauts and to make rocket fuel. It also has peaks that are in constant or near-constant sunlight, which creates excellent opportunities for generating power to support lunar activities.

The Conversation

Mariel Borowitz is an associate professor of international affairs at Georgia Institute of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. The views and opinions expressed

Robert Lea

SPACE.COM

Fri, August 25, 2023

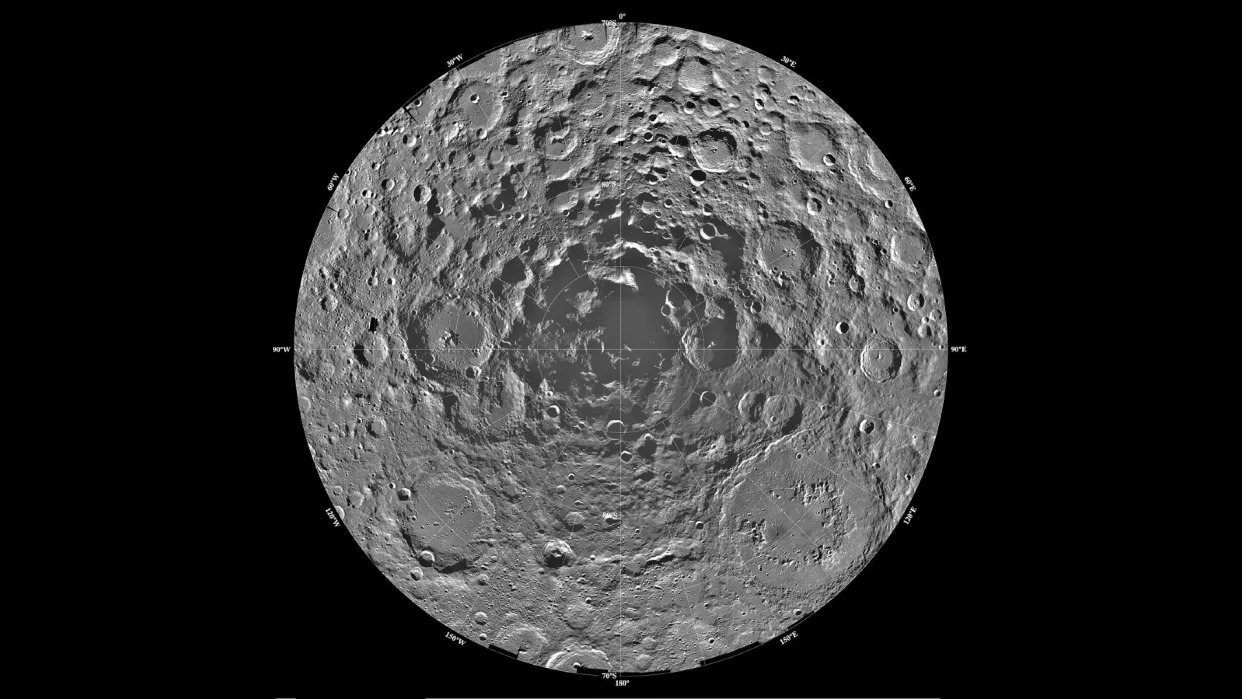

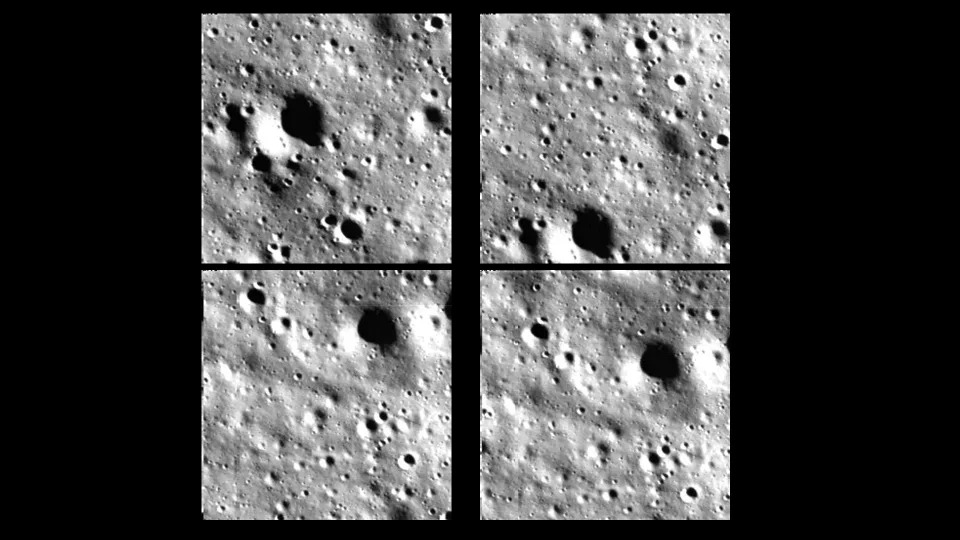

This view of the Moon's cratered South Pole was seen by NASA's Clementine spacecraft in 1996.

India's Chandrayaan-3 mission successfully landed near the moon's south pole on Wednesday (Aug. 23). The Indian Space Research Organization (IRSO) mission not only made history because it saw the nation become the fourth to successfully land on the moon — after the Soviet Union, the U.S. and China — but also because it named India the first to land at the southern lunar pole.

The lander's arrival was marked on the ISRO Twitter account with words from Chandrayaan-3 on the lunar surface: "I reached my destination, and you too!'

But IRSO's mission, which has since deployed a robotic rover to begin exploring the lunar south pole, isn't exactly alone in its goals.

Around 2025, as part of its Artemis 3 mission, NASA plans to have humans step foot on the moon for the first time in 50 years. That journey is also set to include the first woman and person of color to make the trip. But even before that, the U.S. space agency's Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) is expected to explore the southern pole in 2024 during a 100-day-long mission.

And China, with its burgeoning space industry, isn't going to be left out of this lunar south pole action. The country's space agency plans to send the Chang'e 7 mission there in 2026 along with a new moon rover.

So why is all this interest in the lunar south pole heating up? Well, ironically, it's primarily due to something very cool.

Related: See 1st photos of the moon's south pole by India's Chandrayaan-3 lunar lander

The lunar south pole's most precious commodity

Interest in the lunar south pole as a landing site is mainly driven by the fact that scientists know the region hosts water in the form of ice. Water is, of course, essential for life as we know it — but it also has other uses. For instance, it can act as a coolant for equipment and even provide rocket fuel. The latter could be especially useful for a staging mission to Mars launched from the moon someday.

What this means is, as space agencies start thinking about sustainability in space as well as the next era of crewed space missions, the ability to harvest water in-situ on the moon for drinking, cooling machinery, or even breaking down into hydrogen and oxygen to provide breathable air or fuel is of immense value.

Additionally, water on the moon is of pure scientific value. It can be used as a record of geological activity on the moon, such as lunar volcanoes, and even act as an asteroid strike tracker.

While water has been detected across the surface of the moon, the majority of water ice signals come from the poles.

Fri, August 25, 2023

This view of the Moon's cratered South Pole was seen by NASA's Clementine spacecraft in 1996.

India's Chandrayaan-3 mission successfully landed near the moon's south pole on Wednesday (Aug. 23). The Indian Space Research Organization (IRSO) mission not only made history because it saw the nation become the fourth to successfully land on the moon — after the Soviet Union, the U.S. and China — but also because it named India the first to land at the southern lunar pole.

The lander's arrival was marked on the ISRO Twitter account with words from Chandrayaan-3 on the lunar surface: "I reached my destination, and you too!'

But IRSO's mission, which has since deployed a robotic rover to begin exploring the lunar south pole, isn't exactly alone in its goals.

Around 2025, as part of its Artemis 3 mission, NASA plans to have humans step foot on the moon for the first time in 50 years. That journey is also set to include the first woman and person of color to make the trip. But even before that, the U.S. space agency's Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) is expected to explore the southern pole in 2024 during a 100-day-long mission.

And China, with its burgeoning space industry, isn't going to be left out of this lunar south pole action. The country's space agency plans to send the Chang'e 7 mission there in 2026 along with a new moon rover.

So why is all this interest in the lunar south pole heating up? Well, ironically, it's primarily due to something very cool.

Related: See 1st photos of the moon's south pole by India's Chandrayaan-3 lunar lander

The lunar south pole's most precious commodity

Interest in the lunar south pole as a landing site is mainly driven by the fact that scientists know the region hosts water in the form of ice. Water is, of course, essential for life as we know it — but it also has other uses. For instance, it can act as a coolant for equipment and even provide rocket fuel. The latter could be especially useful for a staging mission to Mars launched from the moon someday.

What this means is, as space agencies start thinking about sustainability in space as well as the next era of crewed space missions, the ability to harvest water in-situ on the moon for drinking, cooling machinery, or even breaking down into hydrogen and oxygen to provide breathable air or fuel is of immense value.

Additionally, water on the moon is of pure scientific value. It can be used as a record of geological activity on the moon, such as lunar volcanoes, and even act as an asteroid strike tracker.

While water has been detected across the surface of the moon, the majority of water ice signals come from the poles.

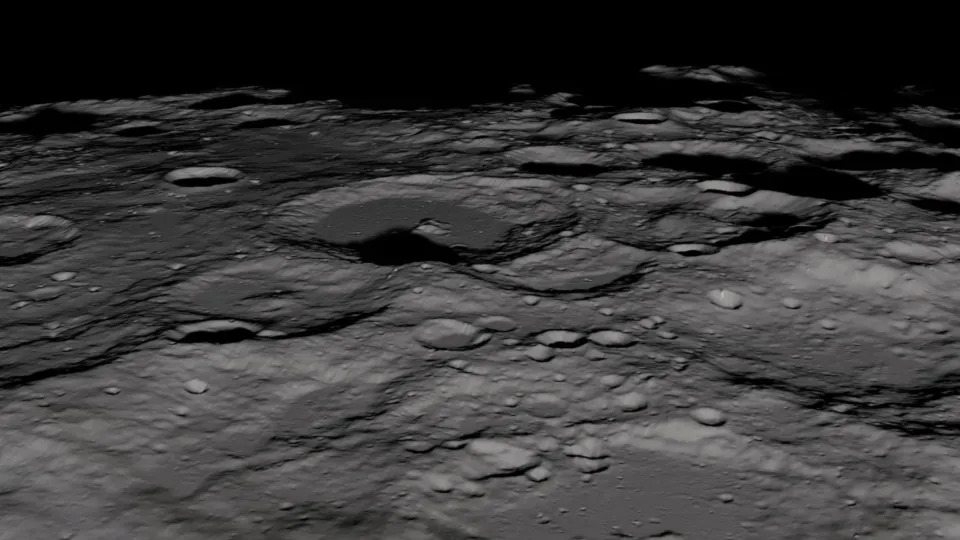

A view of the moon's surface at the lunar south pole obtained by the LRO (Image credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/Scientific Visualization Studio)

At the lunar south pole, only elevated peaks are lit by the sun. This is because the sun is always positioned around the horizon due to the moon's tilt. More low-lying areas are permanently shrouded in shadow, and are quite literally referred to as permanently shadowed regions (PSRs).

Temperatures in PSRs can drop to as low as -418 degrees Fahrenheit (-250 degrees Celsius), which is so frigid its colder than Pluto — but this means it's also an ideal spot to maintain water ice.

Any water molecules that enter a PSR region are immediately frozen. They're also trapped because it is simply too cold for them to evaporate. This water content then falls to the surface, where it gets mixed with lunar soil. That process results in the growth of large "pockets" of water and soil at the moon's south pole.

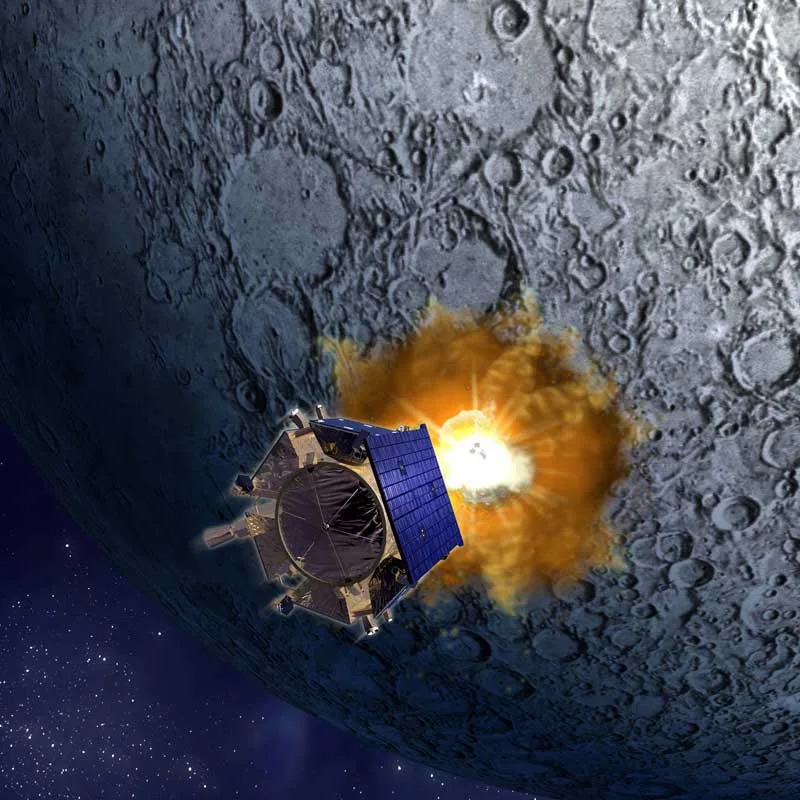

An artist's illustration of NASA's LCROSS mission to crash two probes into the moon and kick up moon dirt on Oct. 9, 2009.

Related Stories:

— What's next for India's Chandrayaan-3 mission on the moon?

— India's historic Chandrayaan-3 moon landing celebrated by ISS astronauts

— India's Chandrayaan-3 moon rover Pragyan rolls onto the lunar surface for 1st time

ISRO was integral in first detecting such lunar water to begin with when, in 2008, its Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft carried a NASA-provided science instrument called the Moon Mineralogical Mapper (M3) to lunar orbit. This determined the existence of water ice inside craters at the moon's south pole.

The following year, in 2009, NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) purposefully slammed a dark crater at the lunar south pole with the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS). This created a plume of debris that LCROSS jetted through, enabling it to detect water ice that had been hidden in darkness.

There was a small concern, however, that the molecule hydroxyl (OH) was confused to be the water molecule (H2O). This fear was allayed in 2020 when it was revealed that data from NASA's Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) telescope confirmed the first unambiguous detection of water at the lunar south pole.

Based upon SOFIA data, scientists estimated there could be as much as 12 ounces of water for every one cubic meter (just over 35 cubic feet) of lunar soil at the southern pole of the moon.

According to the Planetary Society, when considering Chandrayaan-1 and LRO data, the two lunar poles harbor over 600 million tons of water ice. That's enough to fill around 240,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

And this, experts say, is a low-end estimate.

Thus, with such an incredibly valuable resource located around the lunar south pole, it is a wonder space agencies haven't already swarmed to get some space probes there well before ISRO's Chandrayaan-3 mission soft-landed this week.

As it turns out, there is a very good reason for this.

Why haven't we landed at the lunar pole before?

Landing near the lunar south pole is not easy, and part of the reason for this is tied to what makes landing there so desirable in the first place. The shadowy nature of the lunar south pole that helps preserve water ice means a soft landing there is tricky.

Most lunar descent vehicles rely on cameras to guide their final approach to the lunar surface, ensuring to avoid obstacles and hazards such as boulders or craters.

Landing is risky even on well-lit regions of the moon. Just one chance encounter between a boulder big enough to tip a spacecraft and a lander would end in disaster for the mission.

Therefore, the risk increases substantially in the shadowy lunar south pole.

Such risk, in fact, is also magnified by the fact that the lunar south pole lacks large expanses of flat terrain as are found at the moon's equator, for instance. Terrain at both lunar poles is known to be heavily cratered as well as more likely to be sloped and rocky.

A sequence of image of the moon's surface taken by India's Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft during its descent to the lunar south pole.

Moreover, the south pole of the moon can't even be seen from Earth.

This means scientists' knowledge of it comes entirely from spacecraft orbiting the moon like the LRO, which has collected precise information about the region and its terrain.

Any lunar craft that seeks to land at the south pole must also be able to withstand the incredibly cold temperatures found there. Further, the lack of sunlight creating those temperatures delivers another issue, too: A lunar rover that strays into one of the many PSRs at the south pole of the moon will be out of contact with the sun, meaning it can't rely on solar power to operate and must instead have a nuclear power source.

As if all of that wasn't enough, PSRs are also out of the line of sight of Earth, meaning relaying messages to and from mission control in the shadowy regions is challenging to say the least.

Future missions like will take the mapping of the terrain of the lunar south pole to a whole new level, with the VIPER mission in particular hunting for resources that could be mined and exploited by the crew of the Artemis program.

Additionally, orbiters around the moon are scoping out the orb's perilous polar regions for suitable landing zones to limit, if not eliminate altogether, the risks of setting down without threatening mission failure.

And, to paint a picture of these risks, there is at least one space-faring nation that has recently become all too aware of the turmoil that may happen at the lunar south pole.

Just days before the landing of Chandrayaan-3, Russia had planned to make its glorious return to the moon's surface after 47 years with Luna-25, which launched on Aug. 10. But on Aug. 19, Roscosmos announced via its Telegram feed that it had lost contact with the mission.

Luna-25 spacecraft had crashed into the moon's surface during landing preparations.

If it had been successful, Luna-25 would have hunted through the soil of the lunar south pole looking for water ice. “It’s hugely disappointing,” Open University planetary scientist Simeon Barber told Nature.

“It highlights that landing on the moon is not easy.”

India’s robotic lander touches down on the moon, lifting spirits at home and abroad

Alan Boyle

Wed, August 23, 2023

Indian mission controllers cheer the successful touchdown of the Vikram lunar lander. (ISRO via YouTube)

A robotic Indian lander set down safely on the moon today, setting off a wave of pride that reached from Mission Control in Bengaluru to Seattle’s tech community.

“India is now on the moon,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi said over a video link moments after the landing at 6:03 p.m. Indian Standard Time (5:33 a.m. PT). He went on to say that “this success belongs to all humanity.”

A roomful of mission controllers in Bengaluru cheered when the landing was confirmed at the end of a six-week-long space odyssey. “This will remain the most memorable and happiest moment for all of us,” said Kalpana Kalahasti, associate project director for the Chandrayaan-3 mission at the Indian Space Research Organization.

Today’s touchdown added India to an exclusive club of moon-landing nations that also includes the U.S., Russia and China. India’s Vikram lander is the first robotic probe to visit the moon’s south polar region, which is thought to be prime territory for human exploration and settlement.

Soon after the landing, Vikram sent back an image showing its surroundings — including one of the lander’s legs and its shadow:

The lander also returned imagery showing the deployment of its Pragyan rover, which sparked a fresh round of cheers at Mission Control:

Chandrayaan-3 is designed to study the composition of lunar soil as well as the thermal and seismic environment at the landing site, using instruments aboard the Vikram lander as well as the Pragyan rover. Scientists hope the data will shed light on the availability of water ice near the lunar south pole.

But today, the scientific angle was overshadowed by the boost to India’s national prestige. The elation that Indians felt was particularly high — coming four years after the Chandrayaan-2 mission’s lander crashed into the lunar surface, and four days after Russia’s Luna-25 lander met a similarly ignominious fate.

One of Chandrayaan-3’s fans is Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, who was born in Hyderabad, India, and came to the United States more than 30 years ago.

“What an exciting moment for India — and the future of space exploration,” Nadella said in a congratulatory post on X / Twitter.

S. Somasegar, a managing director at Seattle-based Madrona Group, passed along his congratulations as well.

“This is proud moment and another huge step forward as far as advances in science and space go. I am sure every Indian, and for that matter, everybody in the world is genuinely excited when we make significant progress and do something which hasn’t happened before,” Soma, who traces his roots to the Indian coastal city of Puducherry, told GeekWire in an email. “ISRO has had a fantastic track record of making space-related scientific breakthroughs in a cost-effective way, and this is another example of that.”

Samir Bodas, CEO and co-founder of Bellevue, Wash.-based Icertis, told GeekWire in an email that India’s success in space resonated deeply with him.

“As an entrepreneur, I’m always inspired by great achievements like the Chandrayaan-3 moon landing,” said Bodas, who grew up in Pune and still has family there. “As someone with deep ties to India, I’m thrilled and overjoyed to experience this moment of great pride and celebration for all Indians.”

This year is a big one for robotic moon missions: In addition to the failed Russian landing and the successful Indian landing, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency is due to launch its Smart Lander for Investigating Moon, or SLIM, as early as this weekend.

Meanwhile, two commercial U.S. probes are being readied for launch with NASA’s backing. Houston-based Intuitive Machines says its IM-1 lunar lander could begin its mission as early as Nov. 15 with a launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. And Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic says its Peregrine lander is ready to head for the moon with a boost from United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket, currently set for its first liftoff late this year.

Both of those missions will target the lunar south polar region, where reserves of water ice in permanently shadowed craters could theoretically provide drinkable water, breathable oxygen and burnable hydrogen fuel for future explorers and settlers. NASA is planning to send astronauts to the region for the Artemis 3 mission in the mid-2020s.

There’s more to come from India as well: ISRO is getting ready to launch a sun-observing mission called Aditya-L1 next month. It’s also ramping up its Gaganyaan human spaceflight program — and talking with Japan’s space agency about LUPEX, an international robotic mission to the lunar south polar region.

“I am confident that all countries in the world, including those from the global south, are capable of achieving such feats,” Modi said. “We can all aspire for the moon, and beyond.”

More from GeekWire:

No comments:

Post a Comment