Irina Ivanova

Wed, January 3, 2024

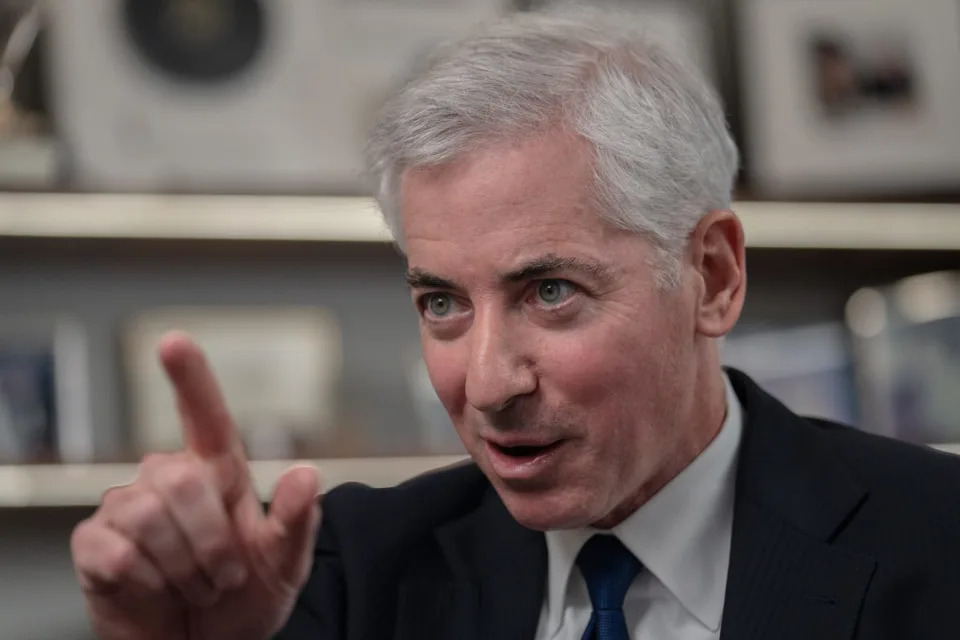

Jeenah Moon/Bloomberg

Bill Ackman scored a victory in his campaign against Harvard when the university’s president, Claudia Gay, stepped down on Monday following allegations she failed to properly respond to antisemitism on campus. Not one to rest, Ackman is now broadening his scope to take aim at Harvard’s overall approach, accusing the institution of falling prey to what he calls “a political advocacy movement” and “ideology” known as DEI that is anti-meritocratic to the core.

According to the billionaire hedge fund manager, the anti-semitism that he had previously accused Harvard of “was not the core of the problem” but merely “a troubling warning sign” of the real issue—an obsession with DEI, or diversity, equity and inclusion, that has grown into something entirely different from the three concepts embedded within the acronym, he said on X on Tuesday.

In the 4,000-word post, Ackman painted DEI as a “movement” that is antithetical to any merit-based program, including capitalism itself. Ackman’s missive appears to be the first mainstream criticism of DEI as “anti-capitalist,” and it widens the scope of a yearslong debate over DEI initiatives that has roiled the business community. Now, instead of DEI being part of a new way of looking at “stakeholder capitalism,” Ackman is accusing it of being an “ideology” harmful to the functioning of a capitalist economy.

“Under DEI’s ideology,” he wrote, “any policy, program, educational system, economic system, grading system, admission policy, (and even climate change due its disparate impact on geographies and the people that live there), etc. that leads to unequal outcomes among people of different skin colors is deemed racist.” By this standard, he continued, “Capitalism is racist, Advanced Placement exams are racist, IQ tests are racist, corporations are racist …” Zooming out in his analysis, he said the use of the lens of “oppression” means that any merit-based program, system, or organization “which has or generates outcomes for different races that are at variance with the proportion these different races represent in the population at large is by definition racist under DEI’s ideology.”

Ackman then accused diversity proponents of censoring dissenting views, akin to the Red Scare of the 1920s and 1950s, which culminated in Congressional hearings to root out suspected communist sympathizers in American industry. Except in Ackman’s telling, DEI proponents are in charge of the institutions and hold the power, while those who disagree with DEI principles “may find [themselves] unemployed, shunned by colleagues, cancelled, and/or [they] will otherwise put [their] career and acceptance in society at risk.”

“The techniques that DEI has used to squelch the opposition are found in the Red Scares and McCarthyism of decades past,” Ackman wrote. A few lines later he called DEI efforts a step “on the path to socialism” that is “inherently inconsistent with basic American values.”

If capitalism is racist, is DEI anti-capitalist?

Ackman’s screed is far from the first attack on DEI in recent years. Diversity initiatives have come under increasing fire from conservatives who claim that such efforts are racist toward white Americans, sometimes lumping them in with other liberal-sounding corporate programs, such as the emphasis on ESG (environmental, social and governance) investing. These programs are rebranded as “anti-white racism” or, in the case of ESG, as discrimination against fossil fuels.

That effort, which culminated in the Supreme Court’s ban on affirmative action in college admissions last year, has been brewing for years. Former President Donald Trump famously banned diversity and sensitivity training in a 2020 executive order, calling it a “malign ideology” akin to stereotyping. States including Florida and Texas have passed laws curtailing discussions of diversity in higher education. Last summer, Republican attorneys general put all Fortune 100 companies on notice about their corporate diversity programs, which observers believe are the next target of the conservative high court.

Versions of corporate diversity efforts have existed since the 1970s, when the federal government formally outlawed workplace discrimination based on sex, race, or national origin. But DEI as branding has truly flourished over the past decade, gaining steam after the 2020 murder of George Floyd and the social outcry for racial equity that it fueled. The late-2010s shift to a more holistic, gentler capitalism held that corporations should consider all of their stakeholders—employees, communities, and customers—in their actions.

“Each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to deliver value to all of them, for the future success of our companies, our communities and our country,” the influential Business Roundtable wrote in 2019, in a statement detailing its members’ commitment to pay fair wages, embrace diversity, do business sustainably, and deal ethically with suppliers. It was a prominent rejection of the shareholder-primacy dogma of the previous four decades which held that a corporation’s only responsibility was to deliver profits to shareholders, a view that critics said verged on psychopathic.

The latest legal and cultural assault from the right, however, puts those goals in jeopardy. And companies are responding to the backlash: Six major corporations, including American Airlines, BlackRock, JPMorgan Chase, and Lowe’s, watered down statements committing to diversity policies, Reuters reported last month.

Ironically, for as much criticism as DEI initiatives are seeing from the conservative camp, they have also been criticized by liberals and leftists for being ineffective in closing racial gaps, perpetuating stereotypes, or even allowing companies a form of reputation laundering. In an extreme example of the latter, The Intercept reported on CoreCivic, the private prison company, touting its support for “principles of diversity, equity and inclusion.” Often, employees themselves are skeptical of these efforts, data shows: 75% of respondents to a Catalyst survey last year in Australia, Canada, the U.K. and U.S. said they believed their company’s racial equity policies were insincere.

Throughout all this, the fundamental problem DEI was ostensibly supposed to solve has remained stubbornly persistent. About one in six Americans is Black, but Black people make up only 4% of leadership at large companies, while the difference between what white and Black workers earn has, by some metrics, remained unchanged since the 1950s.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Column: Angry over antisemitism, billionaires are seeking to cancel free speech on campus Michael Hiltzik Wed, October 18, 2023

Who is Bill Ackman, the hedge-fund billionaire who used corporate-raider tactics to push out Harvard’s president?

Lukas I. Alpert

MarketWatch

Fri, January 5, 2024

Bill Ackman has spent much of his career investing in undervalued companies, demanding change and pursuing very public pressure campaigns — often moving to oust the management or the board. - Matthew Eisman/Getty Images

Bill Ackman’s calls for the removal of Harvard University President Claudine Gay were ripped straight out of a corporate raider’s playbook.

It was a natural approach for the billionaire hedge-fund manager who made his name as an aggressive activist investor. For decades, he amassed his fortune by investing in undervalued companies, demanding change and pursuing very public pressure campaigns — often moving to oust a company’s management or board of directors.

But in the case of Harvard, Ackman used posts on X, the social-media platform formerly known as Twitter, rather than filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, to make his case.

Ackman’s bare-knuckles boardroom tactics in the Gay matter have attracted criticism. The NAACP accused him of racism for going after the first Black president of Americas’ oldest university. Others have charged that he rode an ideologically driven push from the political right against diversity, equity and inclusion measures in academia to get what he wanted.

On Thursday, the Rev. Al Sharpton led a protest outside the offices of Ackman’s fund, Pershing Square Capital Management.

Ackman has denied being driven by racism in his campaign against Gay, countering that efforts to bring more people of color into positions of power, part of the framework known as DEI, are themselves racist because, in his view, they discriminate against white people. Proponents of DEI initiatives say they boost underrepresented groups’ presence in the workplace, create a fairer playing field and foster greater belonging, in addition to being a smart business move.

“DEI is racist because reverse racism is racism, even if it is against white people,” Ackman wrote in a lengthy X post following Gay’s resignation earlier this week. “Racism against white people has become considered acceptable by many not to be racism, or alternatively, it is deemed acceptable racism.”

A spokesman for Ackman said his comments on X speak for themselves.

The Elvis of investing

Ackman made his name through an aggressive approach to investments, building his firm into one of the highest-profile hedge funds in the country, with $18 billion in assets under management. His personal fortune is estimated to be around $4 billion, according to Forbes.

His model has been to focus on a small handful of stock investments, take counterintuitive bets and then make a lot of noise, often putting himself at the center of attention. Among the investor class, he has developed a kind of cult of personality. His research on corporate situations can often be sharp and exhaustive, but sometimes his activist campaigns to shake up corporate boardrooms turn into circuses. He has been called the Elvis of investing .

In some years, Ackman’s fund has outperformed, by huge numbers, many of its rivals and the stock market broadly — for example, making more than $2 billion in profit by shorting the market ahead of the pandemic. His investment in the real-estate investment trust General Growth Properties, in the wake of the 2008 economic crisis, turned into a $3.7 billion profit for his fund. His Pershing Square Holdings returned 26.7% net of fees in 2023, edging out the U.S. stock market, as gauged by the S&P 500 SPX.

Hedge-fund managers like Ackman make money by collecting performance fees, usually 20% of the annual profits generated by investments made in the market. They often also have a significant amount of their own net worth invested in their funds.

Ackman’s brash approach has rubbed many people the wrong way. A decade ago, he lost a fight over a high-profile $1 billion short position he took against the nutrition company Herbalife HLF, which he accused of operating as a pyramid scheme, bringing him head-to-head with famed corporate raider Carl Icahn. Ackman lost big money on Herbalife and disastrous activist positions in J.C. Penney and Valeant Pharmaceuticals .

His hedge fund may have averted disaster by raising $2.7 billion of permanent investing capital in an initial public offering of Pershing Square Holdings NL:PSH PSHZF that Ackman conducted on the Euronext Amsterdam Stock Exchange. When investors in Ackman’s hedge fund started pulling their money out amid the Herbalife, Valeant and J.C. Penney losses, Ackman knew the money he had raised in Amsterdam in 2014 was secure.

It wasn’t the first time Ackman had to deal with a serious threat to his business. He shut his first hedge fund, Gotham Partners, in 2002, after making some bad bets on golf courses. He launched Pershing Square Capital Management two years later.

Following the bruising Herbalife period, Ackman said he was taking a new, lower-key approach to investing, after which Pershing Square had some of its strongest years. His current portfolio includes shares in the likes of Google GOOG GOOGL, Chipotle Mexican Grill CMG and Lowe’s Cos. LOW. Ackman is not publicly demanding anything from the people running these companies.

But old habits die hard.

Harvard ouster

A graduate of both Harvard and its graduate business school, Ackman has long been a substantial donor to the school. He has said over the years that he has frequently offered advice on how the university should be run and how to handle its enormous endowment, but that he has often been ignored.

On X, Ackman said he initially supported Gay’s appointment to Harvard’s presidency in late 2022. But after pro-Palestinian protests on Harvard’s campus following the Oct. 7 attacks by Hamas in Israel that left more than 1,200 Israelis dead, Ackman said, he felt Gay didn’t do enough to make Jewish students feel safe.

After a highly criticized appearance before Congress, in which Gay answered questions about whether calling for genocide against Jews was a violation of Harvard’s policies by saying it depended on the context, Ackman more vocally called for her ouster. (Gay said in a New York Times op-ed Wednesday that she had fallen into “a well-laid trap” at the congressional hearing.)

Gay ultimately stepped down on Tuesday, following investigations by conservative groups and media outlets into her academic work that turned up alleged instances of plagiarism .

Now, in keeping with the corporate-raider playbook, Ackman says Harvard’s board of trustees should also step down, and its DEI office should be disbanded.

He is also turning his attention to Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sally Kornbluth, the only university president who testified in the congressional antisemitism hearing who has retained her job.

Meanwhile, Business Insider has published a report accusing Ackman’s wife, former MIT professor Neri Oxman, of plagiarism. Oxman acknowledged on X that, in her 330-page Ph.D. dissertation, she did not properly place language in four paragraphs in quotation marks and did not properly provide a citation in another sentence, saying she regretted the errors

No comments:

Post a Comment