Archaeology

Researchers find that Żagań-Lutnia5 is an Iron Age stronghold

Date:

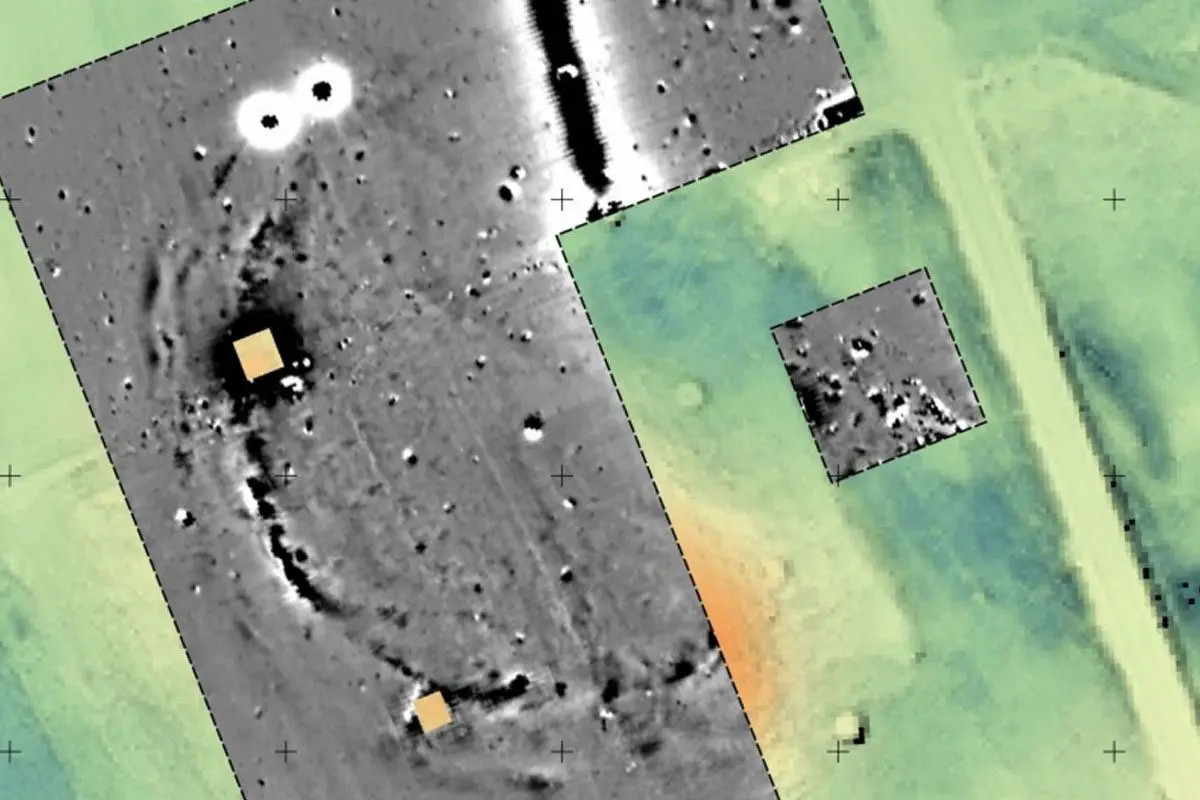

Archaeologists have conducted a ground penetrating radar (GPR) survey of Żagań-Lutnia5, revealing that the monument is an Iron Age stronghold.

Żagań-Lutnia5 was first discovered in the 1960s near the town of Żagań in western Poland, with previous studies suggesting that the monument could be associated with the Białowieża group of the Lusatian urnfield culture.

The Lusatian culture existed in the later Bronze Age and early Iron Age (1300–500 BC) in most of what is now Poland. It formed part of the Urnfield systems found from eastern France, southern Germany and Austria to Hungary, and the Nordic Bronze Age in northwestern Germany and Scandinavia.

A recent study led by Dr. Arkadiusz Michalak on behalf of the Archaeological Museum of the Middle Oder River has revealed two parallel sequences of magnetic anomalies at Żagań-Lutnia5 that represent the remnants of earthen and wooden fortifications.

The course of the fortifications were recorded in the northern, western and southern parts of the study area, however, a study of the eastern section was limited due to a sewage collector built in the 1990’s.

Exploratory excavations found four cultural layers with remains of huts and hearths, in addition to a burnt layer from the last phase of occupation that suggests a period of conflict.

According to the researchers, the monument was likely built by the same people who constructed the stronghold in Wicin and a number of verified defensive settlements within the area of the Elbe, Nysa Łużycka and Odra.

As a result of the study, Żagań-Lutnia5 has been added to the catalogue of verified Early Iron Age strongholds located in today’s Lubusz Voivodeship.

Header Image Credit : Provincial Office for the Protection of Monuments

Sources : Provincial Office for the Protection of Monuments – Archaeological research at the site of Żagań-Lutnia5

February 23, 2024

Archaeology

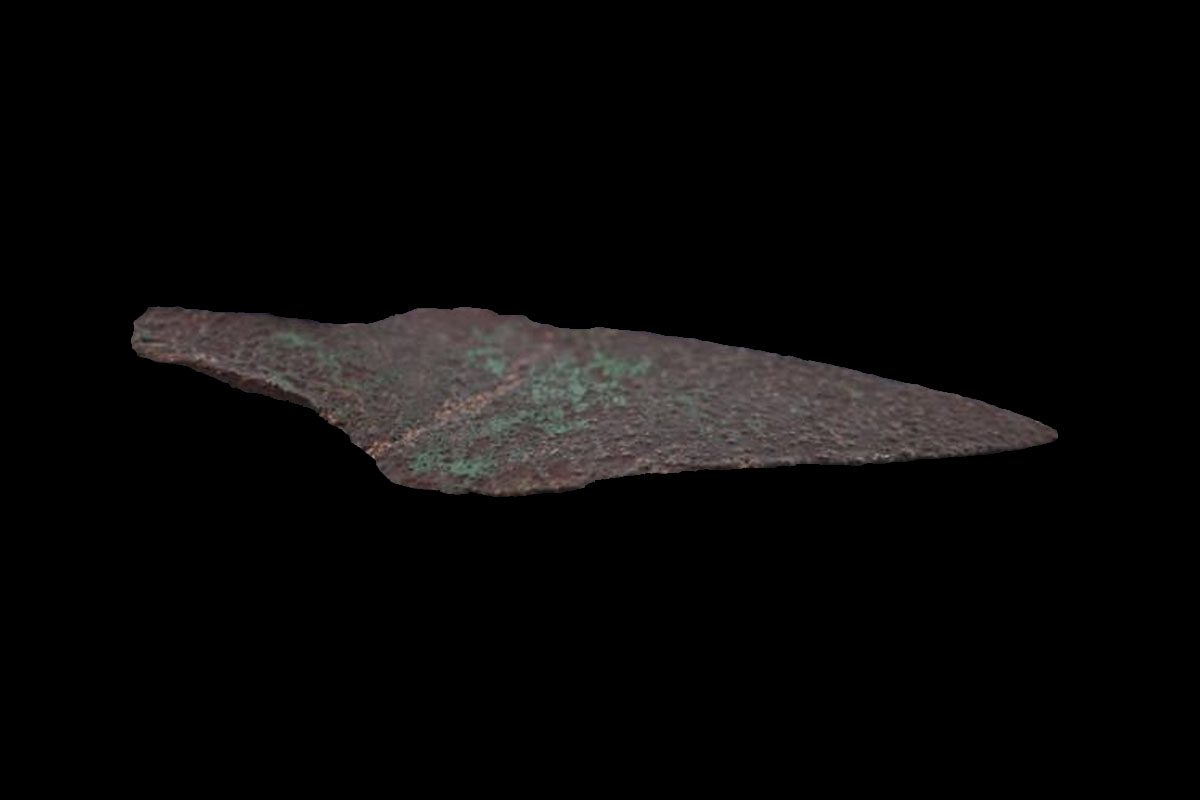

A rare copper dagger from over 4,000-years-ago has been discovered in the forests near Korzenica, southeastern Poland.

Piotr Gorlach from the Historical and Exploration Association Grupa Jarosław made the discovery during a metal detector survey in Jarosław Forest.

Upon realising the significance of the find, Mr Gorlach contacted the Podkarpacie conservator of monuments in Przemyśl and the Orsetti House Museum.

The dagger dates from over 4,000 years ago, a period in which objects made from copper were extremely rare in the Central European Plain.

A preliminary study indicates that the dagger may originate from the Carpathian Basin or Ukrainian steppe, and predates the development of bronze metallurgy for the region.

This transition is traditionally known as the Copper Age and marked a gradual incorporation of copper while stone remained the primary resource utilised.

Dr. Elżbieta Sieradzka-Burghardt from the museum in Jarosław, said: “This is a period of enormous change in the main raw materials for the production of tools. Instead of flint tools commonly used in the Stone Age, more and more metal products appear heralding the transition to the next period – the Bronze Age.”

Daggers during this era were a universal attribute of warriors, however, being made from copper suggests that the owner held a high social status. This is further supported by its size measuring 10.5 cm in length, which for this period is actually very large when compared to other metal objects from the same era.

The dagger has already been added to the collection of the Orsetti House Museum in Jarosław.

Header Image Credit : Łukasz Śliwiński

Sources : PAP – A dagger from over 4,000 years ago found in the forest.

Bronze Age Settlement Found in Switzerland

Friday, February 23, 2024

Possible Royal Ring Discovered in Denmark

Friday, February 23, 2024

Friday, February 23, 2024

Neanderthals crafted sophisticated adhesives from ochre and bitumen.

Neanderthals, our closest extinct cousins who roamed Europe for hundreds of thousands of years before modern humans entered the picture, were more intelligent and resourceful than meets the eye. According to new findings, Neanderthals, crafted stone tools using a multifaceted adhesive that is surprisingly effective and clever.

The researchers analyzed ancient tools excavated from Le Moustier, a renowned archaeological site in France. These tools, dating back to the Middle Palaeolithic period, reveal that Neanderthals were not only skilled craftsmen but also possessed a nuanced understanding of materials.

The ancient adhesive is a mixture of ochre and bitumen on the tools — ingredients that require careful selection and preparation.

This finding challenges the long-standing narrative of Neanderthals as mere brute survivors. Instead, they were quite thoughtful innovators, not all that different from our species and their Stone Age technology. The adhesives discovered suggest a level of planning, experimentation, and environmental knowledge that aligns Neanderthals more closely with early modern humans than previously recognized.

“These astonishingly well-preserved tools showcase a technical solution broadly similar to examples of tools made by early modern humans in Africa, but the exact recipe reflects a Neanderthal ‘spin,’ which is the production of grips for handheld tools,” said Radu Iovita, an associate professor at New York University’s Center for the Study of Human Origins

A recipe from the ancient past

The research, a collaborative effort involving experts from New York University, the University of Tübingen, and the National Museums in Berlin, re-examines artifacts that had been largely overlooked since their discovery in the early 20th century. Some of the stone tools are as ancient as 120,000 years old. The tools, once unwrapped from their decades-long slumber, revealed traces of a concoction that is both simple and sophisticated.

By combining ochre, a natural pigment, with bitumen, a type of natural asphalt, Neanderthals created an adhesive that was effective yet elegant. The mixture was adept at binding stone tools to handles without sticking to the hands, a balance that even modern adhesives may struggle to achieve. This composition facilitates the crafting of durable tools while showing a deeper understanding of material properties on the part of the glue’s craftsmen.

While bitumen alone can act as glue, the addition of ochre in just the right amounts (over 50% in some cases) made the ‘product’ a lot better. The researchers recreated the recipe and performed stress tests, proving the effectiveness of the Neanderthal glue.

“It was different when we used liquid bitumen, which is not really suitable for gluing. If 55 percent ochre is added, a malleable mass is formed,” said lead researcher Patrick Schmidt from the University of Tübingen.

Microscopic analyses further confirmed the use of these adhesives, showing wear patterns indicative of applied grips, not merely accidental smudges. Such evidence points to a deliberate design, pushing back the timeline for complex adhesive use in Europe by thousands of years.

A reflection on human evolution

The implications of this study extend beyond the adhesive itself. The effort to gather materials from distant locations, the precision in mixing, and the application of the adhesive all suggest a level of cognitive sophistication that demands a re-evaluation of Neanderthal society.

Although Neanderthals and Homo sapiens split from a common ancestor roughly half a million years ago, their technological achievements converge into a common thread, suggesting parallel paths of thought and invention.

Previously, researchers uncovered a pendant made from ancient eagle talons and cave paintings in Spain made by Neanderthal artists.

The new study appeared in the journal Science Advances.

No comments:

Post a Comment