🌟The Bright Side: Groundbreaking Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile reveals first images

Washington (AFP) – The Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile published its first images on Monday, revealing distant galaxies and stellar nurseries in the Milky Way with impressive detail. After 20 years in the making, the US-funded telescope gets ready to start repeatedly scanning the sky to create a high-definition time-lapse of the Universe.

Issued on: 23/06/2025 - AFP

By: FRANCE 24

The team behind the long-awaited Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile published their first images on Monday, revealing breathtaking views of star-forming regions as well as distant galaxies.

More than two decades in the making, the giant US-funded telescope sits perched at the summit of Cerro Pachon in central Chile, where dark skies and dry air provide ideal conditions for observing the cosmos.

One of the debut images is a composite of 678 exposures taken over just seven hours, capturing the Trifid Nebula and the Lagoon Nebula -- both several thousand light-years from Earth -- glowing in vivid pinks against orange-red backdrops.

Read more

The image reveals these stellar nurseries within our Milky Way in unprecedented detail, with previously faint or invisible features now clearly visible.

Another image offers a sweeping view of the Virgo Cluster of galaxies.

The team also released a video dubbed the "cosmic treasure chest," which begins with a close-up of two galaxies before zooming out to reveal approximately 10 million more.

"The Rubin Observatory is an investment in our future, which will lay down a cornerstone of knowledge today on which our children will proudly build tomorrow," said Michael Kratsios, director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

Equipped with an advanced 8.4-meter telescope and the largest digital camera ever built, the Rubin Observatory is supported by a powerful data-processing system.

Read more

Later this year, it will begin its flagship project, the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST). Over the next decade, it will scan the night sky nightly, capturing even the subtlest visible changes with unmatched precision.

The observatory is named after pioneering American astronomer Vera C. Rubin, whose research provided the first conclusive evidence for the existence of dark matter -- a mysterious substance that does not emit light but exerts gravitational influence on galaxies.

Dark energy refers to the equally mysterious and immensely powerful force believed to be driving the accelerating expansion of the universe. Together, dark matter and dark energy are thought to make up 95 percent of the cosmos, yet their true nature remains unknown.

The observatory, a joint initiative of the US National Science Foundation and Department of Energy, has also been hailed as one of the most powerful tools ever built for tracking asteroids.

In just 10 hours of observations, the Rubin Observatory discovered 2,104 previously undetected asteroids in our solar system, including seven near-Earth objects -- all of which pose no threat.

For comparison, all other ground- and space-based observatories combined discover about 20,000 new asteroids per year.

Rubin is also set to be the most effective observatory at spotting interstellar objects passing through the solar system.

More images from the observatory are expected to be released later Monday morning.

First celestial image unveiled from revolutionary telescope

Ione Wells

South America correspondent

Georgina Rannard

Science correspondent

The first image revealed by the Vera Rubin telescope shows the Trifid and Lagoon nebulae in stunning detail

A powerful new telescope in Chile has released its first images, showing off its unprecedented ability to peer into the dark depths of the universe.

In one picture, vast colourful gas and dust clouds swirl in a star-forming region 9,000 light years from Earth.

The Vera C Rubin observatory, home to the world's most powerful digital camera, promises to transform our understanding of the universe.

If a ninth planet exists in our solar system, scientists say this telescope would find it in its first year.

Rubin Observatory and the Rubin Auxiliary Telescope in Cerro Pachón in Chile

It should detect killer asteroids in striking distance of Earth and map the Milky Way. It will also answer crucial questions about dark matter, the mysterious substance that makes up most of our universe.

This once-in-a-generation moment for astronomy is the start of a continuous 10-year filming of the southern night sky.

"I personally have been working towards this point for about 25 years. For decades we wanted to build this phenomenal facility and to do this type of survey," says Professor Catherine Heymans, Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

The UK is a key partner in the survey and will host data centres to process the extremely detailed snapshots as the telescope sweeps the skies capturing everything in its path.

Vera Rubin could increase the number of known objects in our solar system tenfold.

Advertisement

A huge cluster of galaxies including spiral galaxies in the vast Virgo cluster, which is about 100 billion times the size of the Milky Way.

BBC News visited the Vera Rubin observatory before the release of the images.

It sits on Cerro Pachón, a mountain in the Chilean Andes that hosts several observatories on private land dedicated to space research.

Very high, very dry, and very dark. It is a perfect location to watch the stars.

Maintaining this darkness is sacrosanct. The bus ride up and down the windy road at night must be done cautiously, because full-beam headlights must not be used.

The inside of the observatory is no different.

There is a whole engineering unit dedicated to making sure the dome surrounding the telescope, which opens to the night sky, is dark – turning off rogue LEDs or other stray lights that could interfere with the astronomical light they are capturing from the night sky.

The starlight is "enough" to navigate, commissioning scientist Elana Urbach explains.

One of the observatory's big goals, she adds, is to "understand the history of the Universe" which means being able to see faint galaxies or supernova explosions that happened "billions of years ago".

"So, we really need very sharp images," Elana says.

Each detail of the observatory's design exhibits similar precision.

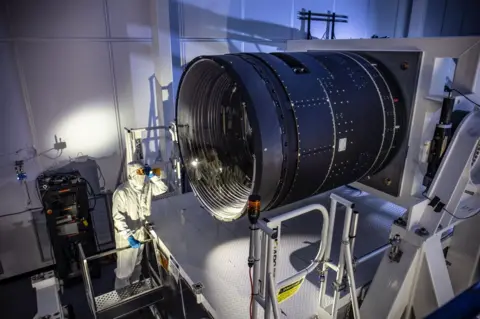

Vera Rubin's is 3,200-megapixel camera was built by the US Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

It achieves this through its unique three-mirror design. Light enters the telescope from the night sky, hits the primary mirror (8.4m diameter), is reflected onto the secondary mirror (3.4m) back onto a third mirror (4.8m) before entering its camera.

The mirrors must be kept in impeccable condition. Even a speck of dust could alter the image quality.

The high reflectivity and speed of this allow the telescope to capture a lot of light which Guillem Megias, an active optics expert at the observatory, says is "really important" to observe things from "really far away which, in astronomy, means they come from earlier times".

The camera inside the telescope will repeatedly capture the night sky for ten years, every three days, for a Legacy Survey of Space and Time.

At 1.65m x 3m, it weighs 2,800kg and provides a wide field of view.

It will capture an image roughly every 40 seconds, for about 8-12 hours a night thanks to rapid repositioning of the moving dome and telescope mount.

It has 3,200 megapixels (67 times more than an iPhone 16 Pro camera), making it so high-resolution that it could capture a golf ball on the Moon and would require 400 Ultra HD TV screens to show a single image.

"When we got the first photo up here, it was a special moment," Mr Megias said.

"When I first started working with this project, I met someone who had been working on it since 1996. I was born in 1997. It makes you realise this is an endeavour of a generation of astronomers."

It will be down to hundreds of scientists around the world to analyse the stream of data alerts, which will peak at around 10 million a night.

The survey will work on four areas: mapping changes in the skies or transient objects, the formation of the Milky Way, mapping the Solar System, and understanding dark matter or how the universe formed.

But its biggest power lies in its constancy. It will survey the same areas over and over again, and every time it detects a change, it will alert scientists.

The Telescope Mount Assembly supports the camera and huge mirrors

"This transient side is the really new unique thing... That has the potential to show us something that we hadn't even thought about before," explains Prof Heymens.

But it could also help protect us by detecting dangerous objects that suddenly stray near Earth, including asteroids like YR4 that scientists briefly worried early this year was on track to smash into our planet.

The camera's very large mirrors will help scientists detect the faintest of light and distortions emitted from these objects and track them as they speed through space.

"It's transformative. It's going be the largest data set we've ever had to look at our galaxy with. It will fuel what we do for many, many years," says Professor Alis Deason at Durham university.

She will receive the images to analyse how far back the stars reach in the Milky Way.

At the moment most data from the stars goes back about 163,000 light years, but Vera Rubin could see back to 1.2 million light-years.

Prof Deason also expects to see into the Milky Way's stellar halo, or its graveyard of stars destroyed over time, as well as small satellite galaxies that are still surviving but are incredibly faint and hard to find.

Tantalisingly, Vera Rubin is thought to be powerful enough to finally solve a long-standing mystery about the existence of our solar system's Planet Nine.

That object could be as far away as 700 times the distance between the Earth and the Sun, far beyond the reach of other ground telescopes.

"It's gonna take us a long time to really understand how this new beautiful observatory works. But I am so ready for it," says Professor Heymans.

In the trace lies the truth: Halogens and the fate of the lunar crust

How halogens uncover the hidden history of lunar crust formation and the striking lunar surface dichotomy.

Ehime University

image:

Around 4.5 billion years ago, the Moon was covered by a global magma ocean. The solidification of the Moon is expected to produce a plagioclase-rich crust. This only appears in the farside of the Moon, whereas the nearside Moon is largely covered by dark erupted basalts.

view moreCredit: Jiejun Jing

On a clear night, the Moon you gaze upon looks the same as it looked for the first humans that walked the Earth --- the same black-and-white side of our nearest neighbor by large dark ‘seas’ and white ‘highlands’ has been facing us for billions of years. The Moon is thought to have been born in a giant impact between our Earth and a Mars-sized other planet, Theia, ca. 4.5 billion years ago. The energy associated with this impact is expected to have led to an ocean of magma covering both the Earth and the young Moon. Cooling of this magma is expected to result in a nearly homogeneous solid Moon, covered with the same crust everywhere. This is not always the case. The hemisphere always facing us, called the lunar nearside, has a totally different appearance than its opposite half, the farside, which is dominated by bright, highland-dominated landscapes, with virtually no ‘seas’ (Fig.1).

The dark lunar ‘seas’ or maria in Latin, are composed of widespread basaltic magmas, mostly erupted ca. 3.5 billion years ago on the nearside, with very few eruption on the far side. This marks a distinct evolution history for these two hemispheres. Why and how did this happened? The secret that shaped the Moon into two worlds may well be buried within minute amounts of halogens (e.g., fluorine and chlorine), found in lunar samples.

Halogen abundances in lunar minerals provide unique insight into the Moon’s evolution, but incomplete knowledge of halogen incorporation in minerals and melts has limited their application. Researchers at the Geodynamics Research Center, Ehime University collaborating with colleagues from Universität Münster (Germany) and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (the Netherlands), carried out high-pressure, high-temperature experiments and successfully derived unique new data on how chlorine (Cl) distributes itself between lunar minerals and co-existing magma. They coupled models of the evolution of the lunar interior to measured halogen abundances in lunar crust samples and found that most lunar nearside samples turn out to be anomalously rich in Cl. In contrast, crustal materials from the lunar farside do not show this Cl enrichment. The researchers provide evidence to link this enrichment to the incorporation of gaseous Cl-compounds by lunar nearside rocks.

This finding indicates that the existence of widespread chloride vapor (with Cl likely present as metal chlorides) was possibly limited to the lunar nearside, suggesting the metal chloride vapor appears to be tied to lunar dichotomy. Considering Cl is highly incompatible and volatile, this vapor-phase metasomatism may be related to (impact-induced/eruption) degassing from extensive lunar mare basalts in the nearside Procellarum KREEP Terrane. Crustal rocks in the lunar farside, without Cl enrichment, are shown to be products from magma derived from lunar interior ca. 4.3 billion years ago. Based on F/Cl modeling, the researchers found that a particular type of lunar crustal rock called the Mg-suite likely originate from a deep mantle which preserves remnants of the initial lunar magma ocean that was present 4.5 billion years ago.

Chlorine-rich vapors released during eruptions (or impact-induced evaporation) played a key role in transforming the Moon’s nearside that human can see. Meanwhile, the farside crust, invisible to us all, escaped from these vapor-associated volcanic activities and thus preserved more pristine information about the Moon including about the lunar magma ocean that formed right after the Moon was born. This finding illustrates the scientific value of recent lunar space missions that focused specifically on studying the lunar far side.

Journal

Nature Communications

DOI

Unlocking faster multiplexing for 6G low-earth orbit satellites

Through key innovations in receiver design, researchers achieve faster data rates with less power and circuit area

Institute of Science Tokyo

image:

These images depict the receiver developed in the study, which was implemented in a small integrated circuit and mounted on a printed circuit board for testing purposes.

view moreCredit: The 2025 Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits

A novel time-division MIMO technology enables phased-array receivers to operate faster with exceptional area efficiency and low power, as reported by researchers from Institute of Science Tokyo. The proposed system significantly reduces circuit complexity for 5G and 6G networks, including non-terrestrial nodes, by reusing signal paths through fast switching. It demonstrated a record-setting 38.4 Gbps data rate across eight streams in a 65 nm CMOS integrated circuit.

The next generation of wireless communications technology, 6G, promises ultra-high data rates and wide coverage that will transform how we connect globally. Central to this vision are non-terrestrial networks using low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites, which will enable seamless integration between terrestrial and satellite networks. To realize this ambitious goal, advanced phased-array antennas capable of multi-beam operation are essential, as they allow the simultaneous transmission and reception of multiple radio beams across various directions and ranges.

Multiple-Input Multiple-Output (MIMO) technology is also crucial for addressing the increasing data throughput demands of future 6G networks. MIMO increases a network’s capacity through multiplexing, which involves sharing the same radio channel for multiple signal streams. However, conventional MIMO systems face a significant challenge: circuit complexity grows proportionally to the product of the number of antennas and MIMO streams, making the integration of large-scale MIMO systems extremely difficult. This issue becomes even more pressing in satellites, where weight, size, and power consumption constraints are paramount, limiting the practical deployment of traditional MIMO architectures.

To address these limitations, a research team led by Professor Kenichi Okada from the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo), Japan, has developed a groundbreaking solution. Their work, presented at the 2025 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits held from June 8–12, 2025, introduces a novel time-division MIMO technology that enables phased-array receivers to operate much faster than conventional systems while maintaining exceptional area efficiency and low power consumption.

The key innovation lies in the team’s proprietary non-uniform time-hopping approach, which achieves high-speed beam switching within the phased-array antenna module without the need to scale the circuit according to the number of MIMO streams. Unlike traditional systems that rely on spatial multiplexing, this design reuses the signal paths for different streams through fast, random switching, significantly reducing chip area requirements.

The researchers implemented a receiver in an integrated circuit using a 65 nm silicon CMOS process, incorporating high-speed switching phase shifters to enhance the device’s resistance to interference. The system integrates eight signal paths with synchronized switches and operates at an impressive clock frequency of 3.2 GHz. Through over-the-air measurements, the team demonstrated remarkable performance capabilities. The receiver successfully achieved 4×4 MIMO signal reception for both horizontal and vertical polarizations, delivering a maximum data rate of 38.4 Gbps across eight streams. “Among recently reported millimeter-wave phased-array MIMO receivers, this device demonstrates the highest bit rate with the best area efficiency achieved to date,” explains Okada.

Overall, this technology represents a crucial advancement for 6G. By enabling multi-beam capability in LEO satellites while maintaining compact circuit size and low power consumption, the innovations presented in this study pave the way for practical large-scale MIMO systems that can support the demands of next-generation wireless networks. “The developed receiver can be integrated into the Internet of Things and mobile devices for both 5G and 6G, as well as LEO satellites. It is a major step forward toward the commercialization and application of new communication services that leverage high bit rates, including non-terrestrial networks,” remarks Okada.

Further efforts in this field will hopefully help us realize the vision of a fully connected Earth, leveraging terrestrial and satellite networks in ways thought impossible only a few years ago.

This work is partially supported by the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT) in Japan (JPJ012368C00801).

Developing an ultra-compact phased-array transceiver for 6G applications | Science Tokyo News

https://www.isct.ac.jp/en/news/iig8wa1xp0ny

Okada Laboratory

https://www.ssc.p.isct.ac.jp/en/

About Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo)

Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo) was established on October 1, 2024, following the merger between Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) and Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech), with the mission of “Advancing science and human wellbeing to create value for and with society.”

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

A Ka-Band 8-Stream Phased-Array Receiver with Time-Hopping Blocker Rejection for 6G Applications

No comments:

Post a Comment