Now is the time for the democratic left in Canada to develop a workable and comprehensive version of basic income as a key policy instrument, and not a sideline consideration.

Basic income is a paradigm-shifting idea on how to ensure economic security for everyone. It is an idea has been discussed and often debated by social democrats and those on the democratic left for many years. This article is a contribution to this discussion from someone who does research on and writes about basic income, but who has also played an active role in the basic income movement in Canada for fifteen years.

Canadian basic income advocates are part of a movement for basic income that is international in scope. It is a multi-faceted and ecumenical amalgam of national and sub-national advocacy groups, civil society organizations, policy experts, academics, campaigners, and research institutes. Important leadership on the global level have been provided since 1986 by the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN). The basic income movement in Canada was launched with the 2008 founding (as a national chapter of BIEN) of the organization now called the Basic Income Canada Network. Since then, many other basic income advocacy organizations have emerged at national, provincial and local levels, including (at the national level) Coalition Canada: Basic Income, UBI Works, and Revenu du base Québec. These organizations are working for an equitable and feasible version of basic income for Canada and have taken a very deliberate non-partisan approach to their work. They have received support from across the political spectrum,[1] including from the late Senator and prominent Conservative Hugh Segal, in convention resolutions passed by the federal Liberal Party, from current and former NDP Members of Parliament, and from the Green Party of Canada (who have supported basic income for over twenty years).

Canadian advocates of basic income have become increasingly invested in a particular model of basic income that they want to see implemented in this country. This model would target lower income people (rather than a being a demogrant that is paid to everyone). It would complement (but not necessarily replace) elements in the broader income support architecture at the level of the federal government, leaving intact the large social insurance programs of Employment Insurance and the Canada/Quebec Pension Plans. In February 2023 three national advocacy organizations, the Basic Income Canada Network, Coalition Canada: Basic Income, and UBI Works, endorsed a Consensus Statement on a Basic Income Guarantee that outlines the principles and general design for a feasible basic income program for Canada.[2]

This essay first surveys views on basic income found on the democratic left in Canada. Consideration will be given will to how negative and sceptical views about basic income on the left are addressed by the Consensus Statement. Following this survey, elements in the Consensus Statement (as well as some key points drawn from broader basic income sources) will be considered alongside core tenets of social democracy as articulated in the Broadbent Principles for Canadian Social Democracy. Lastly, some suggestions will be made on how the basic income model of universal economic security could reshape our conception of social democracy as we confront the existential threats of economic and social inequality, rising right-wing authoritarianism, and the ecological emergency.

Critical Perspectives of Basic Income on the Left

There has been an array of reactions to the idea of (universal) basic income among social democratic thinkers, activists, and politicians.[3] Outright opponents include those who object to the “universal” aspect of “universal basic income.” They see basic income as an inefficient and wasteful use of public funds in that it is not targeted to those who need income support the most. Another general concern of these critics is that basic income will serve as a neoliberal ‘trojan horse.’ This argument assumes that while low-income people would be provided with a modest unconditional cash benefit. At the same time further cuts to public services would be justified. Further in this telling of a possible basic income world, all of us (including those whose only income is a paltry amount of basic income) will have to fend for ourselves in the profit-seeking marketplace to secure necessities such as health care, education, or affordable and decent housing.

The efficiency and trojan horse objections to basic income have been found both among neoliberals but also on the left in recent years. But there are now social democratic voices expressing more open-minded views on basic income. MacEwan et al. (2020) tentatively and conditionally endorse basic income in their 2020 report Basic Income Guarantee: A Social Democratic Framework from their vantage point at the Broadbent Institute.[4] They do fear that basic income may be seen as a “silver bullet” or a “quick fix solution” to poverty and economic insecurity. But the report’s authors do conclude in a positive vein that “there are concrete steps that we can take to make a basic income more feasible in the future and help to address poverty right now.”

On the other hand, MacEwan et al. couch their support for basic income in this way:

A host of labour market policies such as full employment, residency status for migrant workers, employment standards, training supports, and union density interact with income support programs and must be taken into consideration. In Canada, addressing these questions is the responsibility of different levels of government, making any implementation of a basic income even more complicated. Designing a program that meets the expectations of social democrats will not be simple.

This assertion that basic income “complicates” the achievement of other social democratic goals such as lowering unemployment and decent jobs is a questionable framing. The implementation of any new social program–be it basic income or say an expansion of the public healthcare system – “complicates” the overall operation of the welfare state, so it is not clear why basic income is unique in this regard.

Additionally, basic income is not a complicated program in the sense that its goal is simply to ensure that people have sufficient income to live a good life. In fact, Canada already maintains an array of federal income support programs, including the Guaranteed Income Supplement for seniors, the Canada Child Benefit for families with children, and the GST refund for low-income people. A fully implemented basic income could be paid out through the existing tax-and-transfer system that these existing programs already use. In this sense, basic income is less complex than the other aspirational goals identified by MacEwan et al. (2020) such as “full employment” or “training supports.” Implementing basic income does not require social democrats to abandon these other goals, and in fact may help to achieve them. In another recent Canadian study by Dwyer et al. (2023),[5] it was found that simply giving homeless people money could be helpful in addressing their other difficult and complicated social needs, and in facilitating their access to in-kind supports. The potential outcomes out of an administratively simple program are far-reaching.

It may be that social democratic hesitancy or half-hearted support regarding basic income is a case of the perfect becoming an enemy of the good. Some social democrats will not give basic income their unequivocal support unless various other desirable policies are already in place and all the consequences can be foreseen. However, there are instances in Canadian social welfare history when progressive politicians, government officials, and advocates made social policy ‘leaps of faith’ that push forward on equality, even though all of the complications or consequences of a new program were not in view. This was the case when workers’ compensation was implemented in the early twentieth century, when unemployment insurance was launched in 1940, and when public health insurance was extended across the country in the latter part of the 1960s. Progressives pushed forward nonetheless, and people benefited. Perhaps it is time for social democrats to make such a ‘leap of faith’ with basic income. This leap would not be made without any foresight either; there is already substantial research and policy learning on basic income to guide the design and launch of an effective and sustainable program that fits the current context in Canada.

It is still important to consider the critical research to understand where basic income’s limitations can occur. A recent comprehensive and noted critique of basic income from a progressive perspective came from Green, Kesselman and Tedds (2021).[6] This report was commissioned by the provincial NDP government of British Columbia as part of its legislative supply and confidence agreement with the BC Green Party in 2017.[7]

In their final report, Green, et. al., concluded that “the needs of people in this society are too diverse to be effectively answered simply with a cheque from the government.” The authors seemed to assume that a ‘stand-alone’ basic income was what Canadian advocates were calling for. However, prominent national organizations advocating for basic income in Canada have proposed a basic income that becomes a part of the existing social welfare system, meeting the social needs in Canada. The 2023 Consensus Statement of basic income advocates strongly emphasized that basic income needs to be embedded in an array of public services such as health care, social housing, food security measures, child and elder care, and other aspects of Canada’s welfare state.

In particular, basic income could be a transformative alternative to the existing model of provincial social assistance, given that it is inadequate, stigmatizing, and dysfunctional.[8] [9] Basic income advocates also hold the view that such a program would support people not assisted by federal social insurance programs such as Employment Insurance or the Canada Pension Plan. A made-in-Canada and income-tested version of basic income could in fact operate like, and be built out from, existing federal income support programs such as Old Age Security, the Guaranteed Income Supplement for seniors, the Canada Child Benefit for families with young children, and the GST Refund, and the Canada Workers Benefit for low income people.[10] [11] [12]

On a conceptual level, Green, et. al., claim that,

A basic income emphasizes individual autonomy—an important characteristic of a just society. However, in doing so it de-emphasizes other crucial characteristics of justice that must be, in our view, balanced: community, social interactions, reciprocity, and dignity.

In fact, research on and advocacy for basic income have presented multiple rationales for basic income that are grounded in the goals of economic justice, social solidarity, freedom from domination, and environmental sustainability.[13] [14] [15] To be sure, there are certainly tensions and sometimes contradictions among these various rationales, but to portray basic income as being primarily about “individual autonomy” as Green, et. al., portend distorts Canadian and international debates about basic income that have been ongoing for many decades.

Advocacy for Basic Income on the Left

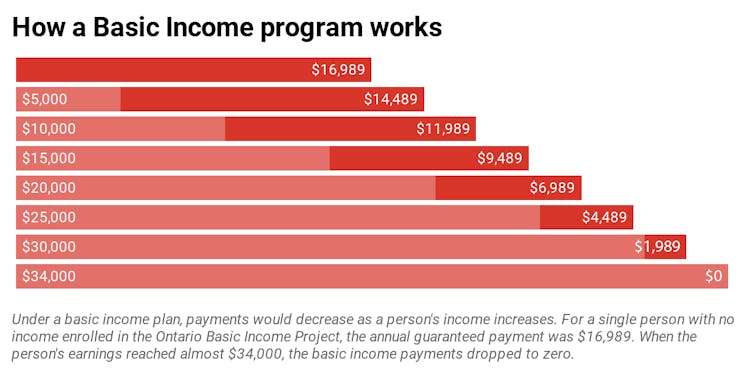

The Consensus Statement calls for a version of basic income in Canada that is income-tested where “benefit amounts will be determined based on taxable income with provisions to rapidly accommodate significant changes in income and family composition,” and where “benefits will be reduced gradually as other taxable income increases.” This targeted model of basic income would cost much less than a universal demogrant. The income-tested model of basic income would also avoid having to tax back the benefit from high income earners (presuming that such a demogrant would in fact be taxed). Such a clawback process would result in a great deal of ‘churn’ and in the tax-and-transfer system, and in higher tax rates for high income earners that would likely provide ammunition for parties on the right that campaign against taxation in general.

On the argument that basic income would lead to additional cuts to in-kind programs of the welfare state, neoliberals who are intent on shrinking social welfare provision have not had to wait for basic income to make their cuts. They have been eroding welfare programs for several decades now, and basic income has only received serious discussion and consideration in Canada for the last ten years or so. To make cuts to social programs, neoliberals have not had to rely on the promise of a basic income to justify austerity.

That said, it is also true that basic income advocates must be wary about basic income becoming a new rationale for cutting social programs. The Consensus Statement addresses this question directly by opposing the “either/or” framing of having to choose between basic income or basic services. These points are contained in the Statement:The basic income guarantee should be an essential component of broad publicly funded universal supports and services.

The basic income guarantee will not replace any publicly delivered social, health or educational services.

The basic income guarantee will not restrict access to any current or future benefits meant to meet special, exceptional, or other distinct needs and goals beyond basic needs.

Given the need for clarity and debate, advocates for basic income on the left have also engaged in critical discourse from a social democratic perspective. An important policy voice on the left in Canada is the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA). One of CCPA’s early considerations of basic income was structured as an inventory of pros and cons.[16]

The CCPA has continued to publish constructive analysis on basic income that incorporates the views of critics and supporters of basic income, and a collection edited by Himelfarb and Hennesey (2016) is particularly notable in this regard.[17] Himelfarb and Hennessey expressed a degree of openness to basic income, and in their introductory remarks, the co-editors questioned the modest incrementalist approach that has characterised Canadian progressive policy to address poverty reduction and economic precarity in recent years. Himmelfarb and Hennesey see basic income as, “the kind of jolt that breaks the mould. Maybe this is a step in a new direction — and new directions are in great need right now.”

Guy Caron, a former NDP Member of Parliament from Quebec who ran unsuccessfully for the federal NDP leadership in 2017, has also been advocate for basic income among Canadian social democrats. During his leadership campaign Caron made basic income a central plank in his platform, and since leaving federal politics, in 2020 Caron produced a brief Broadbent Institute explainer to articulate on a “guaranteed minimum income.”[18] In this explainer, he argued that such an income-tested benefit could be implemented by the federal government based upon its experience with the COVID-19 Pandemic policy measures implementing the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). In Caron’s view, Ottawa should take the initiative with this program, and then seek to engage provincial governments to coordinate their programs with guaranteed minimum income. In the social democratic spirit, Caron presents his basic income proposal as complementary to job creation, progressive labour market policies, and improvement in public services; not as a substitute for such measures.

Labour movement leaders and progressive economists have also expressed their supportive views for basic income in Canada. Canadian economist Jim Stanford for instance sees basic income as a program that will strengthen workers, including unionized ones.[19] Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic income support programs such as CERB, Stanford (2022) views that:

The core principles that no-one should live in poverty, that we can afford a decent living standard for everyone, that protecting the poor strengthens the well-being of us all, are more within our reach than for many decades. … [T]hinking big about universal income security is appropriate and inspiring. And done right, it can both strengthen and unify the struggles of trade unionists and anti-poverty advocates.

In a similar vein, researchers associated with the Labour Studies Department at McMaster University have focused on basic income as a measure to address labour market precarity and economic insecurity of working people.[20] [21] Building on a multi-year research project on Poverty and Employment Precarity in Southern Ontario, they also studied the Ontario Basic Income Pilot Project, implemented in select Ontario communities in 2018, and subsequently cancelled by the then incoming Progressive Conservative provincial government. From this brief but substantial study, Ferdosi et al. (2020) concluded that, “the stability basic income provides can help recipients move to better paying employment and to play a fuller role as citizens in society,” and that basic income “has the potential to improve the physical and mental health of participants and reduce their demands on public health resources.”[22]

Canadian Political Developments on a Social Democratic Basic Income

As outlined above, basic income has received a substantial defence on the Canadian left among the ranks of labour, politics, and academia. An overarching question, however, is whether or not Canada’s social democratic party—The New Democratic Party of Canada and its provincial wings—will make basic income a policy priority and a central plank in their election campaign platforms. In the 2021 federal election, the federal NDP platform made the policy commitment to enact:

“A livable income when you need it […]

With the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, we have seen what’s possible when governments mobilize to make a livable income a priority.

… we’ll get to work right away building towards a guaranteed livable income for all Canadians.

In time, New Democrats will work to expand all income security programs to ensure everyone in Canada has access to a guaranteed livable basic income.”

In this framing, the federal NDP appeared to offer only vague, rhetorical support for basic income. Following the 2021 election, the NDP caucus forged a Parliamentary supply and confidence agreement in March 2022 to prop up the minority Liberal government in exchange for NDP legislative priorities. In this agreement public programs for dental care and prescription drugs were at the top of the priority list; however, improved income security programs were not part of the agreement.

There are, still, federal NDP caucus members that have pushed the basic income agenda forward. In December 2021, NDP MP Leah Gazan introduced a private member’s Bill (C-223 – An Act to develop a national framework for a guaranteed livable basic income) in the House of Commons. This bill directs the Minister of Finance to take one year to “develop a national framework for the implementation of a guaranteed livable basic income program throughout Canada for any person over the age of 17, including temporary workers, permanent residents and refugee claimants.” An identical Bill (S-233) was introduced in the Upper Chamber by Senator Kim Pate, where it received second reading and was sent to Committee for further study in April 2023.

Over the last several years social democrats in Canada have warmed to the idea of basic income as a new approach to ensuring economic security for all, despite the continued hesitancy of centering such a program as a foundational plank of a progressive policy platform.

Canadian social democrats can move beyond basic income as just an ‘add on’ policy to their many existing political objectives and build on principles of unconditional economic security for all to reshape our model of social democracy. To build a Canada that is just and equitable, outlined as the central objective of the Broadbent Principles for Canadian Social Democracy, basic income holds the potential to addressing the gaps in economic and social rights.

There are various (but often generally similar) definitions of “social democracy.” One that is helpful for this discussion is offered by Ben Jackson (2013) is that of:

An ideology which prescribes the use of democratic political action to extend the principles of freedom and equality valued be democrats in the political sphere to the organization of the economy and society, chiefly by opposing the inequality and oppression created by laissez-faire capitalism.[23]

Basic income advocates in Canada take a rigorously non-partisan approach that embraces no political ideology, be it social democracy, liberalism, conservatism, or whatever. Nonetheless, a case can be made that the current preferred model of Canadian basic income advocates, as articulated the 2023 Consensus Statement, is one that aligns closely with social democratic principles and as a complement to its strong systems of social welfare.

Given this convergence with basic income advocates, there is an opportunity for Canadian social democrats, including the New Democratic Party, labour unions, and social movements of the broad democratic left, to focus on a made-in-Canada model of a basic income guarantee in their social advocacy and political campaigning.

Basic Income and the Reformulation of Social Democracy

There are certainly opportunities for basic income and its convergence with social democratic principles, and so Canadian social democrats must go beyond supporting it as a worthwhile policy idea and make basic income implementation a key plank in election platforms.

Fundamentally, social democrats should embrace the basic income model of economic security as one aspect of a broader project of rethinking the tenets of social democracy. Engaging in such a radical re-think gives social democrats an opportunity to develop effective responses to existential and global crises faced by society such as economic inequality and precarity, the rise of right-wing authoritarian populism, and the ecological emergency.

This is no small task, to be sure, but there are several pivotal issues around which we can begin to construct a new model of social democracy that incorporates, and complements, a basic income.

i) Basic Income and Social Reproduction

Some feminist theorists are concerned that basic income could trap women in unwaged reproductive labour roles,[24] but others take a more positive position. Kathi Weeks (2020) discusses how basic income can address the failure of heteropatriarchal family in late capitalism to properly count economic contributions, especially the unpaid reproductive labour of women, and to distribute income in a more fair and efficient way.[25] In a similar vein, Nancy Fraser (2016) links the struggle for a basic income with other progressive causes, including campaigns for a shorter work week, public childcare, housing, rights of migrant domestic workers, and environmental protection, and sees the programmatic change sought by social movements as a “new way of organizing social reproduction.”[26] Nedelsky and Malleson (2023) argue that basic income merits consideration as part of a suite of policy measures that could enable a transition to a society in which all of us work part-time so that we can fully engage in care work within the family and community.[27]

Social reproduction and care work are matters on which social democrats have had much to say. Social democrats have fought for, and frequently achieved, programs that provide public, accessible childcare, as well as financial and practical support for family caregivers. Building on this historic struggle, a social democratic version of basic income could better support family care work regardless of gendered roles. Such a program could also help lower the number of hours in the standard work week; could enable easier transitions between unpaid and paid work; and could ensure better access to good jobs for women and other groups who have been historically disadvantaged in the labour market.

For the purposes of election campaigning, social democrats could present clear and comprehensive family policies grounded in basic income principles that would address the crisis in social reproduction. Such a package of policies could conceivably gain broad public support. Most people in Canada can relate directly and powerfully with the challenges of family care, economic survival in a precarious labour market, and the time poverty that results from the demands of both paid labour and unpaid care work. Social democrats should develop flexible and nuanced responses to these challenges using the basic income approach.

ii) Basic Income and Political Participation

Canadian social democratic political parties campaign in elections to win seats and form governments, but they also connect with Canadians to form durable social alliances that achieve progressive political goals and go beyond election campaigns. Social democrats themselves are found in the ranks of unions, women’s organizations, coalitions fighting racism and trans- and queerphobia, and many other civil society groups.

Unfortunately, it is not apparent that these coalitions and alliances have formed a resilient and sustained political movement for reshaping Canada along social democratic and left-progressive lines. On the other hand, in recent years we have seen in Canada the remarkable growth of authoritarian, right-wing populism that has been aided immensely by echo chambers of social media on the internet. Right-wing populism gained significant momentum during the COVID-19 pandemic, with its opposition to public health measures such as vaccination mandates. How can the democratic left build a populism of its own to counter the rise of these right-wing forces that are racist, xenophobic, antipathetic towards democratically elected political leaders, contemptuous of scientific research, and sometimes neo-fascistic?

This is a complex question that cannot be fully addressed here, but it plausible to suggest that one driver of right-wing extremism is a deep and abiding economic anxiety about the future. This anxiety is an outgrowth of precarious employment, rising costs for necessities such as groceries and housing, and attenuated access to public goods such as health care. There are other sinister forces at play, for sure, such as white supremacist groups spreading their propaganda, and libertarian politicians undermining the very legitimacy of governments and public policy. Still, economic insecurity and uncertainty surely plays a role in fuelling right-wing populism.

Senator Kim Pate and MP Leah Gazan have argued that this economic insecurity and anxiety could be addressed in part by setting in place a basic income guarantee for all.[28] This would not be a panacea—in fact, basic income is derided and opposed by right-wing populists who are deeply suspicious of public policy measures that redistribute wealth. Nonetheless, basic income, along with other policy innovations and moral clarion calls from the left, may help to restore the faith of Canadians in collective and perhaps universal measures to look after one another through public programs, and the various levers of government power under democratic control.

iii) Basic Income and Social-Ecological Transition

An increasingly prominent understanding of today’s ecological imperative points towards a steady-state economy and a post-growth society in which basic income plays a central role, when the limits of growth encroach on the present environmental emergency. Social democrats must consider social welfare beyond its dependence on economic growth in the current capitalist mode of production—a different political economy in which scarcity is overcome through radical redistribution within and between countries, to avoid the worst consequences of the environmental emergency.

Basic income ought to be a necessary policy choice in this scenario, in place of the notion of “full employment” construed as all working-age adults being continually employed in full-time paid work. Social democrats must search for policies that support full social engagement in socially necessary and useful (paid and unpaid) work, bearing in mind the need for gender justice as discussed in the section on social reproduction immediately above.

Basic income, once again, would be part of a mix of policies in a social-ecological transition guided by social democratic principles. Such a transition would lead us to more modest and local ways of life, but also to greater economic security and personal fulfillment in a political-economic order that is equitable, just, inclusive, and sustainable.

Basic Income for Canadian Social Democracy

Even during the ‘Golden Age’ of the western social democratic welfare program, thoughtful and influential social democrats have endorsed basic income. In September 1968, Ed Broadbent gave his inaugural speech as a newly elected Member of Parliament, where he identified “the absence of a guaranteed annual income” as one of the “serious deficiencies that still remain” in the “structural components of the modern welfare state.”[29]

Now is the time for the democratic left in Canada to develop a workable and comprehensive version of basic income as a key policy instrument, and not a sideline consideration. Canadian social democrats should incorporate the principle of guaranteed, unconditional and universal economic security as a fundamental program for its vision a better society. Such a commitment could reshape and renew our understanding of social democracy and move us forward in our continuing quest to build a better Canada.

FURTHER READING

Bank of Canada Independence Vs. Accountability

ISSUE NO. 1 – SPRING 2024 | JOURNAL

April 2, 2024

Dave McGrane

The origin of the concept of central bank independence is a critique of social democratic ideas prevalent during the middle part of Friedman’s career.

Trad-Wives and Hustle-Bros: Contemporary Rejections of Late-Stage Capitalism

ANALYSIS

March 6, 2024

Alexandra Ages

The “trad-wife” and “hustle-bro” subcultures are a phenomena of the social media age, and a symptom of late-stage capitalism.

A Common Platform for a Green Industrial Transformation

OPINION

February 6, 2024

Clay Duncalfe, Clement Nocos, Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood

Across Canada, public investments totalling $188 billion over five years in these key priorities are urgently needed to drive a prosperous green transformation.

Perspectives is a Canadian Journal of Political Economy and Social Democracy by the Broadbent Institute.

SUPPORT OUR WORK

© 2023 Broadbent Institute. All rights reserved.