America’s most wholesome comic wanted to remake the comics world in its image.

A new exhibit at Olin Library, “Domesticated Pulp: Archie Publications and the Comics Code,” which runs through December 17, includes ephemera from the Archie offices, including editorial policy, printer’s proofs and original artwork.

By Rosalind Early

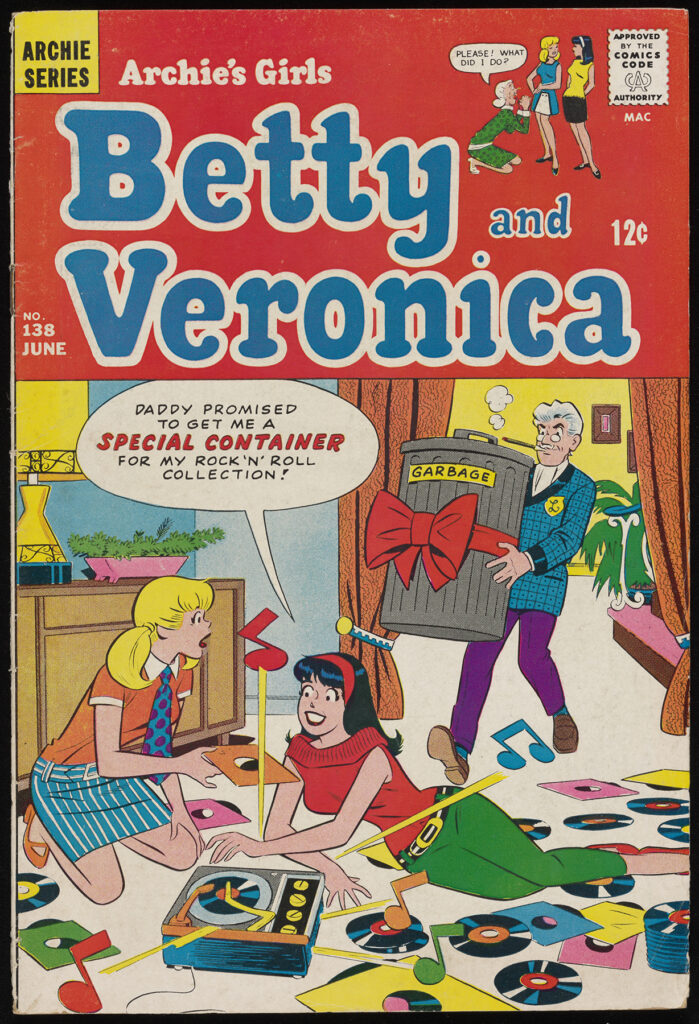

Fans of Riverdale, the CW TV show based on the Archie Comics series, might be surprised to learn that in the comic books Archie Andrews never went to juvie and Veronica Lodge never ordered a hit on her father. Archie and the gang were actually a byword for wholesome, an idealized portrait of small-town American youth where the teens faced problems like making a mess when tie-dying clothes, getting up early to run charity races and making fun of Archie’s old jalopy.

“You get a vision of teenage life that has wacky hijinks but none of the angst and loathing actual teenagers experience,” says D.B. Dowd, a nationally known illustrator and professor of art in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts.

Introduced in 1941, Archie was as popular as it was long-lasting, but Archie’s impact on comics goes further than its popularity.

Archie publisher John Goldwater led a self-censorship organization — the Comics Code Authority (CCA), which set the decency standards for pulp publications — that would homogenize comics for decades. Without the CCA’s seal of approval, comic book publishers were essentially cut off from wholesale distribution.

Goldwater and Archie’s impact is the subject of a new exhibit in the Newman Tower of Collections and Exploration at Olin Library, “Domesticated Pulp: Archie Publications and the Comics Code.” The exhibit, which runs through December 17, includes ephemera from the Archie offices, including editorial policy, printer’s proofs, original artwork from illustrators Bob Montana and Don DeCarlo, and more.

The Archie Comic Collection, which includes more than 100 pieces of original works of art, was amassed by notable cartoonist, author and collector Craig Yoe and acquired by the University Libraries in 2020. The collection is just one of many housed in the Dowd Illustration Research Archive, which aims to preserve the history of illustration and visual culture.

“It was a trove of stuff,” says Dowd, who curated the exhibit along with Andrea Degener, interim curator of the Dowd Illustration Research Archive. But the exhibit is more than just Archie, it tells the history of pulp publishing in the United States and how the Comics Code Authority re-shaped the industry.

“The Archie Comic Collection provides a unique study of how Goldwater leveraged the code to promote the long-term success of the Riverdale universe,” Degener says. “Before the advent of Archie, Goldwater published titles like Close-Up and Dash, which were essentially pin-up magazines categorized in the men’s humor genre. But he seemed to sense an opportunity with the popularity of Archie and began branding Archie Comics as wholesome and appropriate for readers of all ages well before the code was even established.”

Pulp publishing, the rise of an industry

The 1930s saw the rise of “what we think of as ‘pulp’ publishing,” although cheap printing for the working class dates to the 19th century. Printed on inexpensive paper were humor comics like in the newspaper, but also detective comics, crime and horror comics, girlie magazines with pin-ups and, later, superheroes.

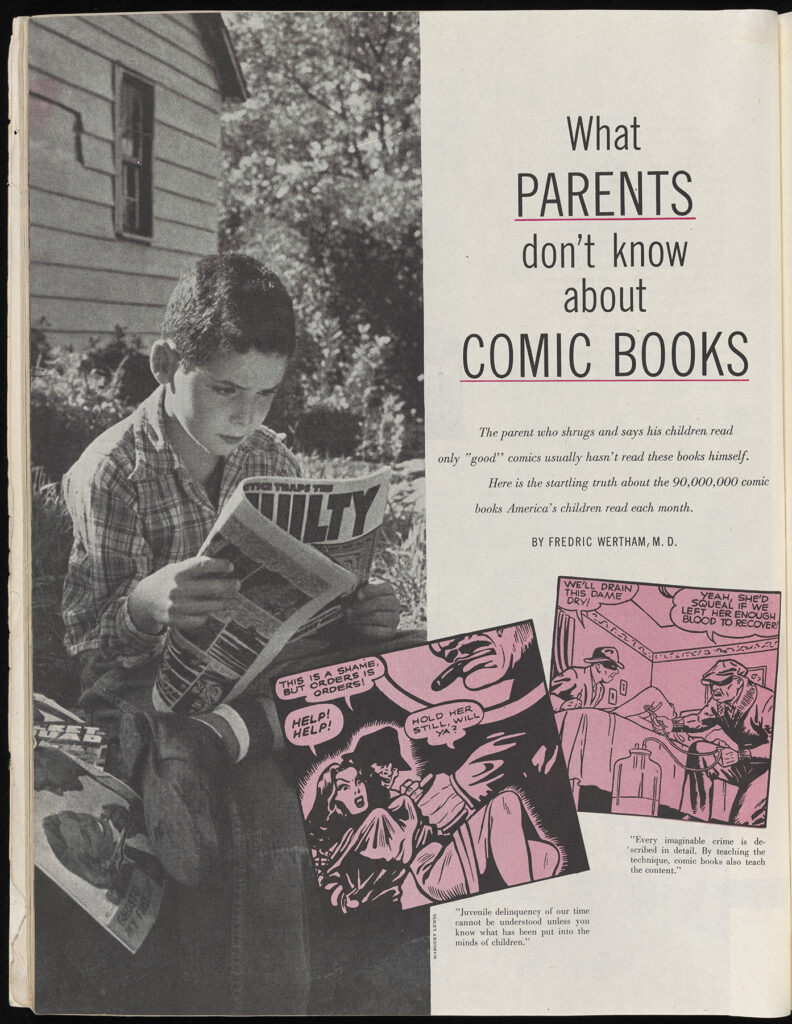

“There’s lots of experimentation,” Dowd says. The work was “aimed at a working-class audience, and a lot of immigrants read pulp magazines.” But kids liked pulp a lot, too, and some of the content was alarming to experts, most prominently Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist, who wrote Seduction of the Innocent that claimed comics caused juvenile delinquency.

Wertham’s outcry led to Senate hearings in 1954. William Gaines, the publisher of Entertaining Comics (EC), was advised against taking the stand. His company had titles like The Haunt of Fear, Tales from the Crypt and Vault of Horror. The covers often featured scantily clad women in danger — the exact comic books Wertham was critiquing. One of EC’s covers, “Crime SuspenStories Vol 1 No. 22,” featured a man holding a bloody hatchet in one hand and the implicitly decapitated head of a blonde woman in the other. Her body is on the floor at his feet. Gaines was asked if he thought this was appropriate.

“Yes sir, I do, for the cover of a horror comic,” Gaines replied. “A cover in bad taste, for example, might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it.”

“For the most part, the Comics Code just eliminated a whole bunch of comics. A variation of the code — one that would have rated the comics for various age groups — would have been preferable.”Rebecca Wanzo

The public was scandalized. By the fall of 1954, publishers formed the Comics Magazine Association of America and the Comics Code Authority to burnish their industry’s reputation and keep the government from censoring them. As a result, comics had to adhere to certain decency standards: no sex before marriage, no pin-ups, no comics with “horror,” “terror” or “weird” in the title, etc. This meant EC had to end most of its lines.

“For the most part, the Comics Code just eliminated a whole bunch of comics,” says Rebecca Wanzo, chair and professor of women, gender and sexuality studies in Arts & Sciences and author of The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging. “A variation of the code — one that would have rated the comics for various age groups — would have been preferable.”

The rise of the Comics Code Authority

Behind the censorship was Goldwater, who served as president of the Comics Magazine Association of America for 25 years. He had the market cornered on wholesome: Archie had proved so popular after being introduced in a Pep comic that the company, formerly MLJ Comics, renamed itself Archie Comics. And the editorial policy was clear, as a memo in the exhibit from the company explains: “Archie Andrews is a positive force; he provides wholesome, non-violent entertainment in the role of the clean-cut, ‘typical American teenager’ we wish all teenagers were.” (Emphasis theirs.)

“Archie is very much Americana. It was an answer to quiet the adult critiques that comics were the cause of rebellious youth culture,” Degener says. “For several decades, Archie Comics was the only publication with a teenage cast that could speak to both a younger and slightly older demographic. The problems faced by the cast were very cyclical and simple; the predicament was always resolved by the end of the comic and in a way that satisfied both adult and youth readership.”

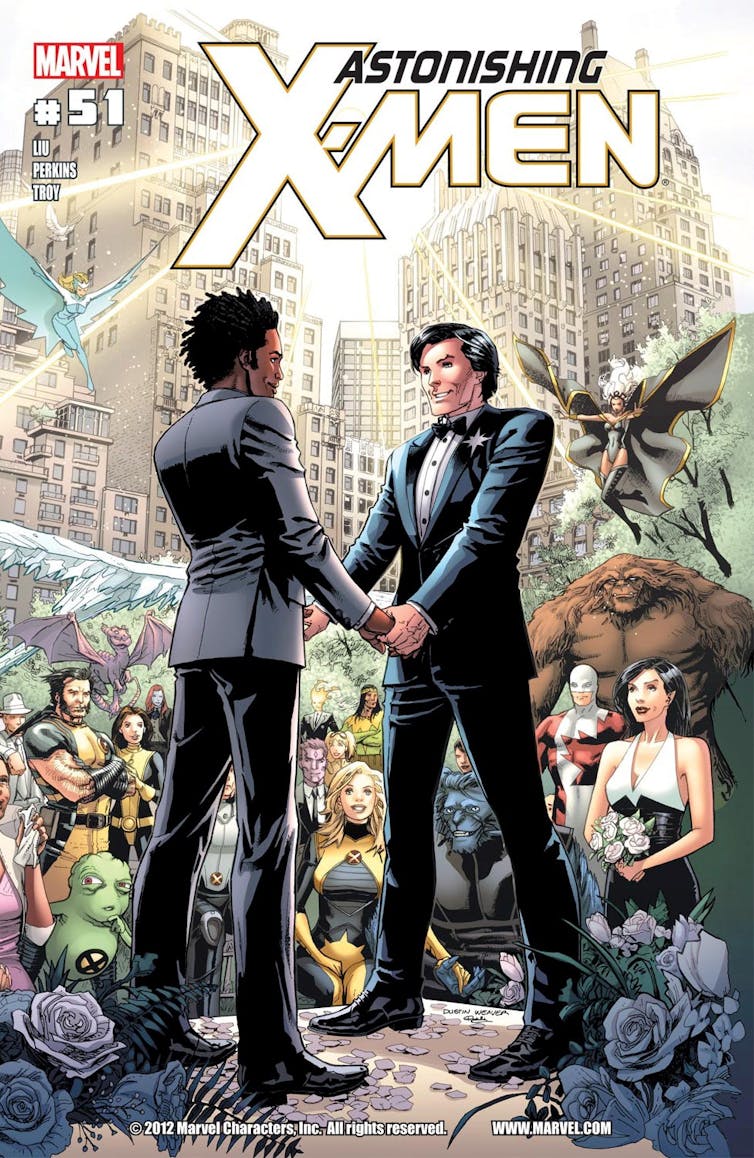

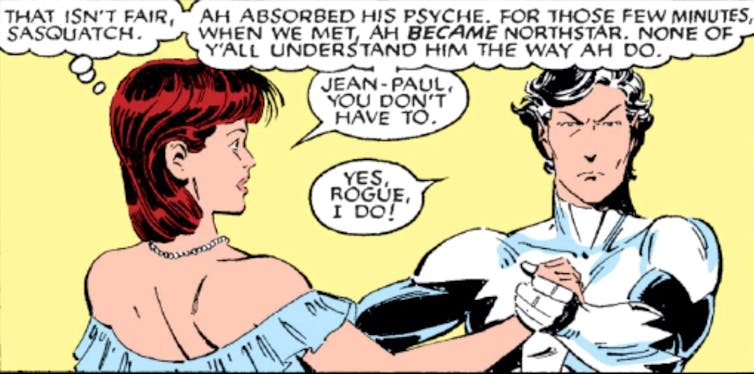

Goldwater exported his attitude about “typical” Americans to the rest of the industry. “The fixation on the typical was highly normative and majoritarian: Racial minorities were invisible, heterosexuality unquestioned, and gender roles strictly enforced,” a placard in the exhibit points out. “Critics were already speaking out against the ‘conformism’ of the 1950s, and John Goldwater is poorly remembered by the insurgents who created alternative comix in the 1960s.”

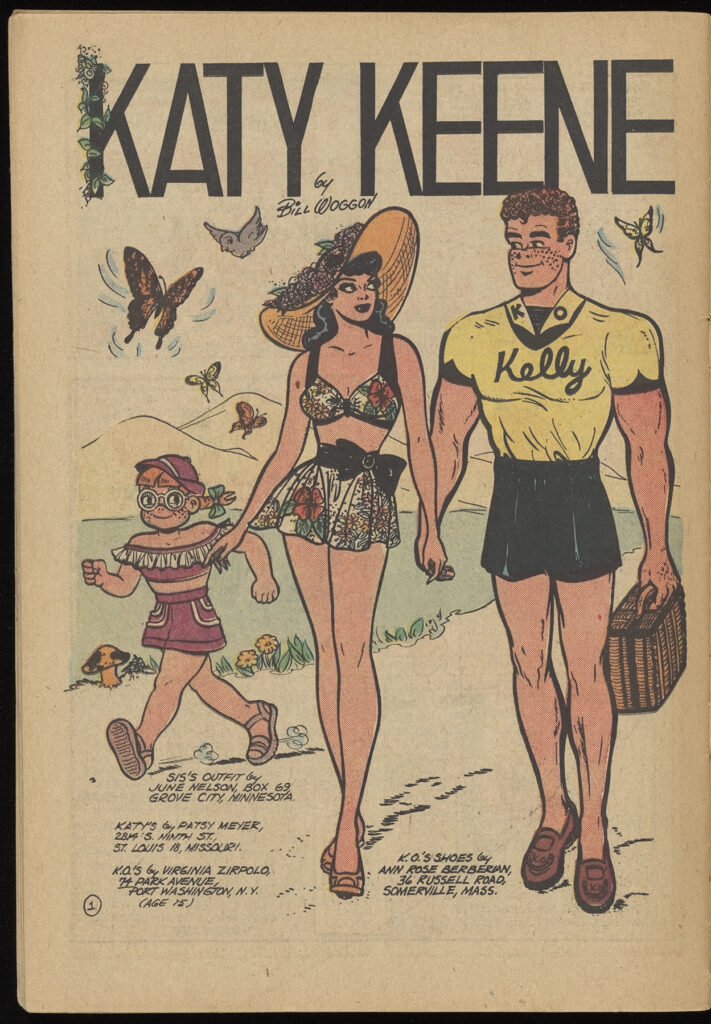

Plus, Dowd argues, Goldwater skirted his own rules, particularly with regard to pin-ups. Betty and Veronica both regularly modeled fashions in pin-up-like poses. Katy Keene, a spinoff in the Archie Comics world, was the worst offender, always striking a pin-up pose as she pulled on her stockings or powdered her nose. The excuse for all this leg? Keene was supposed to be modeling fashions that had been suggested by readers.

“Katy Keene is an interesting study because her character sets the precedent for Betty and Veronica’s famous fashion specials and one-on-one dialogue with readers,” Degener says. “Katy Keene was glamorous, and she was always followed around by her younger sister, Sis, who aspired to be like Katy. Katy even had her own fan club.”

“The term pin-up refers to a whole woman shown in an illustration in a cheese-cakey way,” Dowd says. “Betty, Veronica and Katy Keene are like pulp vixens. There’s never any sexual content, but there’s certainly a sense of buried sexuality that’s in this wholesome package. That’s why we called the exhibition ‘domesticated pulp,’ because that’s what Archie did.”

Censorship, then and today

Today, school and public libraries face scrutiny about the books they carry. Across the country, Republicans have introduced laws or regulations to prevent kids from accessing “illicit material” that is not that illicit, such as Fun Home, a graphic memoir about author Alison Bechdel’s family and struggles with her sexuality.

But Wertham was not a conservative. “Wertham was a pretty progressive psychiatrist,” Wanzo says. “He was interested in the problems of racism being represented in comics and things like that.” (This problem may have been exacerbated by the CCA, which once took issue with a Black man being depicted as an astronaut, for instance, despite that not being against the Comics Code.)

Still, the excuse for the censorship, protecting the youth, is a common refrain. “Young people are going to find ways to access things they want to access,” Wanzo says. “But there’s a tension between what the state should do in terms of regulating content and what providers should do.” She points out that parents should be able to regulate what their child sees, but not be able to eliminate legal content that others may want to see.

“The desire to control what young people encounter in the world — and the danger that they will think thoughts that aren’t ours — is deeply unattractive.”D.B. Dowd

“There are ways to talk about content,” she says.

Most publishers stopped using the Comics Code Authority by 2001, and they’d been pushing against the CCA for decades with comics like Watchmen.

One of the earliest publishers to push against the CCA was Gaines. He eventually left the pulp industry and started MAD magazine to circumvent the CCA, and for decades, the groundbreaking publication didn’t even have ads so it could be fully independent. (Learn more about MAD at another comics-focused exhibit: “MADness Unleashed: The World of MAD Magazine” in Olin Library on Level 1 of the Kagan Grand Staircase. The exhibit runs through January 28.)

Despite essentially fostering MAD magazine, very little redeems the CCA in the eyes of most comics and illustration fans. “The desire to control what young people encounter in the world — and the danger that they will think thoughts that aren’t ours — is deeply unattractive,” Dowd says.