Published April 27, 2020 By Amanda Marcotte, Salon- Commentary

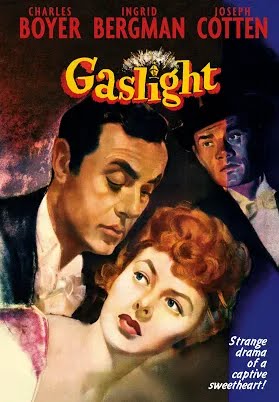

It’s gone mainstream in recent years, but the word “gaslighting” used to be an esoteric term from the world of psychology and domestic abuse counseling. The word refers to the 1944 film “Gaslight,” in which Ingrid Bergman plays a woman whose husband tries to drive her insane by hiding her belongings and otherwise manipulating her environment, and telling her that the changes she perceives are all in her head. Experts in domestic violence developed the term to describe the way that abusers in real life try to manipulate victims. The gaslighter works by denying reality, often when the facts are plain as day, with such conviction and repetition that the victim starts to question themselves and the evidence of their own senses

For instance, this might take the form of the abuser denying that he hit his victim or falsely claiming that she provoked it, and then browbeating her until she accepts the lie and even starts to wonder whether she imagined the whole thing.

Under Donald Trump’s administration, however, the term has ventured into politics. It’s become a way to talk about how Trump and his defenders won’t merely tell lies, but will stand by even the dumbest and most obvious lies, holding their ground until the defenders of reality simply give up fighting. This started from the very beginning of the administration, when Trump and his administration claimed his inauguration crowd was bigger than Barack Obama’s, and insisted on repeating that lie and intimidating government agencies into backing it up. Needless to say, this has continued throughout the coronavirus pandemic, dialed up to an extreme.

One might wonder why we need a term with such a complicated back story, when the word “lying” is right there for the taking. The reason is that Trump lies so frequently and in such varying ways that it’s useful to have a taxonomy of Trump lies to understand the various ways his lies work and how best, perhaps, to resist them.

With garden-variety lying, the liar tends to assume the target doesn’t know the truth and so can be made to accept the lie as if it were truth. Gaslighting differs dramatically in that the target actually knows what’s true. They experienced it, heard it or witnessed what really happened themselves. So what the gaslighter must do is convince the target to reject the evidence of their own eyes and ears.

Gaslighting is a useful term to explain what Trump did throughout this past weekend, in response to what we at Salon are calling “Lysol-gate,” in which our president went on national television and suggested that injecting household cleaners into people’s lungs might be a clever idea to fight the coronavirus that the medical profession clearly hadn’t thought of yet.

The reason doctors haven’t considered this idea is that it will kill the patient — and, I guess, also any virus lurking in his or her lungs. Trump is literally too stupid and lazy to know that fact, which was deeply embarrassing for him and anyone who supports him.

The problem Trump faces here is that he’s right there on video, marveling about “the disinfectant, where it knocks it out in a minute” and speculating about an “injection inside, or almost a cleaning, because, you see, it gets in the lungs,” and pompously instructing the federal officials tasked with managing this crisis to investigate this possible treatment.

In the wake of widespread outrage, mockery and meme-creation, Trump turned to gaslighting. The goal is to deny the evidence of our own eyes and ears with such shamelessness and persistence that people start to question whether they heard what they heard, or at least give up trying to insist on the truth.

Trump’s first gaslighting attempt was to try to pretend he was pranking the press, telling a group of reporters the next day: “I was asking a question sarcastically to reporters like you just to see what would happen.”

This is a classic example of how gaslighting differs from plain old lying. Trump is insisting here that those of us who heard him suggest injecting disinfectants in people’s lungs have broken brains — if we didn’t detect the slightest hint of sarcasm in his tone, it’s because we are defective in some way, not because he wasn’t actually being sarcastic. The point is to force people who heard him perfectly well to defend their own ability to hear and see things, knowing full well that there’s no definitive, objective way for human beings to “prove” that they know the difference between sarcasm and not-sarcasm.

But at the same time Trump was implying that only crazy people with broken brains didn’t detect his supposedly obvious sarcasm, he also suggested that only crazy people with broken brains heard him say the word “lungs.” To repeat, he suggested an “injection inside, or almost a cleaning, because, you see, it gets in the lungs.”

“I do think that disinfectant on the hands could have a very good effect,” Trump told reporters later.

This is more gaslighting. It’s about trying to make people question whether, in their eagerness to criticize Trump, they misheard or misinterpreted him. (Never mind that rubbing bleach or Lysol or other household disinfectants on your hands is also a bad idea, since they will burn your skin.) His two arguments contradict each other — he couldn’t simultaneously have been messing with reporters and making an earnest argument about hand-washing — but in a sense, that’s the point. What the gaslighter wants to do is disorient the target so they begin to question their own sense of reality. Flooding them with a bunch of confusing and logically incoherent claims suits that goal.

All these insignificant points of litigation — was he talking to Dr. Deborah Birx or Homeland Security Undersecretary Bill Bryan when he made his “injection” comment? Was he talking about the virus itself or merely the fear of the virus when he said “hoax”? — are also forms of gaslighting. It’s about seizing on minor but irrelevant details the target may have gotten wrong to imply that the target’s sense of reality is irrevocably damaged and therefore they can’t be trusted to understand anything at all.

An abuser in a marriage, for instance, might use the fact that his wife once forgot that his favorite shirt is purple, not red, to argue that she is too stupid and crazy to be trusted when she says that he hit her or that he won’t let her see her friends. Trump is pulling the same trick, using minor confusion over the details of that specific press conference as “evidence” that people didn’t hear him correctly when they heard him suggest injecting disinfectants into people’s lungs.

Because gaslighting works differently than garden-variety lying, it requires a different response. With garde- variety lying, it’s often just a matter of supplying a fact check. But gaslighters put the person who is being lied to on the defensive, and try to make the debate over whether the target is mentally stable enough to be trusted, not the content of the gaslighter’s lies. Trump wants the debate to be about what’s in our heads, which is ultimately insubstantial and unprovable, not what the entire world heard him saying with his own mouth.

Defeating gaslighting often requires more of a meta-response. Rolling the tape over and over to confirm that we all heard Trump say the words he actually said certainly helps, but it’s not enough. It’s important to resist getting mired in line-by-line debates over whether people who are horrified by Trump’s disinfectant comments got the color of his tie right. Instead, we should call out these kinds of diversionary tactics, which are meant to force us into a debate about whether our minds are broken and whether we can literally perceive anything at all. That’s not the issue. The issue is that our president is a lazy, arrogant moron who went on TV and spewed fatuous bullshit about how maybe doctors should look into shooting up patients with poisonous chemicals because, y’know, it’s worth a shot.