In Canada they are celebrated in song by Gordon Lightfoot with his Great Canadian Railway Triology.

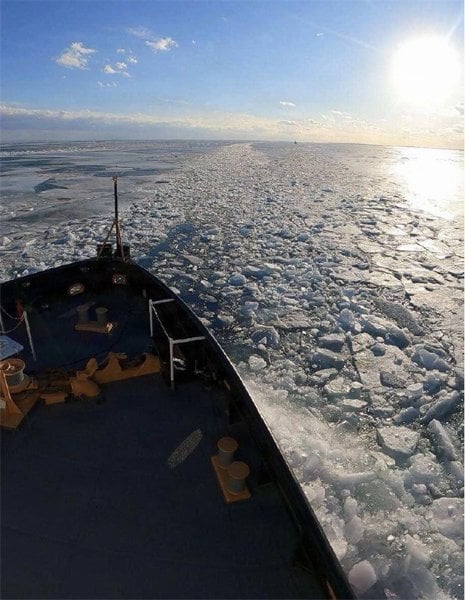

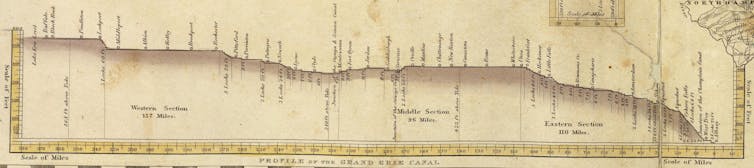

Navvies built canals, railways, dams and then pipe tracks, the big nineteenth century sea-port docks, and the Manchester Ship Canal.

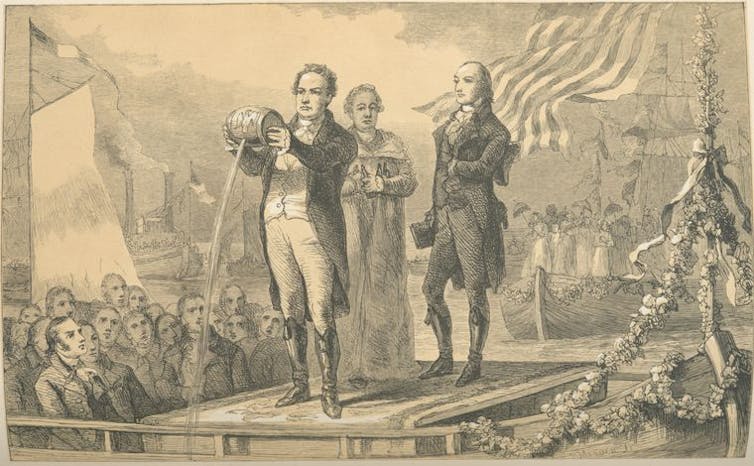

Navvying began suddenly in 1763 in the Bridgewater Canal: it ended around 1943, after a twenty-year fade-out. Along with the rest of Britain there was a kind of kink in the navvy's history in the 1870s when things began changing, generally for the better.

At first they were just skilled earth shifters digging canals at prodigious speed. Later they were skilled in tunnelling, mining, timbering — skilled enough to set up as one-man contractors employing local unskilled labourers to shift their muck. You could set a gang of prime navvies down in an untouched valley, they said of themselves, and they'd build you a dam without aid of an engineer. At times they slotted into the pay scales at twice a common labourer's wages, though they never equalled apprenticed craftsmen like masons.

It is easy for the urbanised and pensionable to romanticise them. They seem free, fearless above the humdrum conventions of shopkeepers, clerks, factory workers, vicars, and the legally wed. Perhaps we glamorise cowboys, blue-water sailors and the hell-bent navvy for the same reasons. In reality, isolation was the biggest thing in a navvy's life. They were perpetual outsiders: a people apart. Sub-working class. Sub-the-bottommost-heap of English working society. Sub-all, almost.

Left: Railway Navvies. Right: Navvies, 1890s

Click on thumbnails for larger images.

The navvy never called a spade a spade, always a bloody shovel. Everything he shovelled he called muck. Earth, blasted rock, clay, all were generically and indiscriminately muck. With the muck he created new landscapes and changed old societies. It was mass transformation by muscle and shovel.

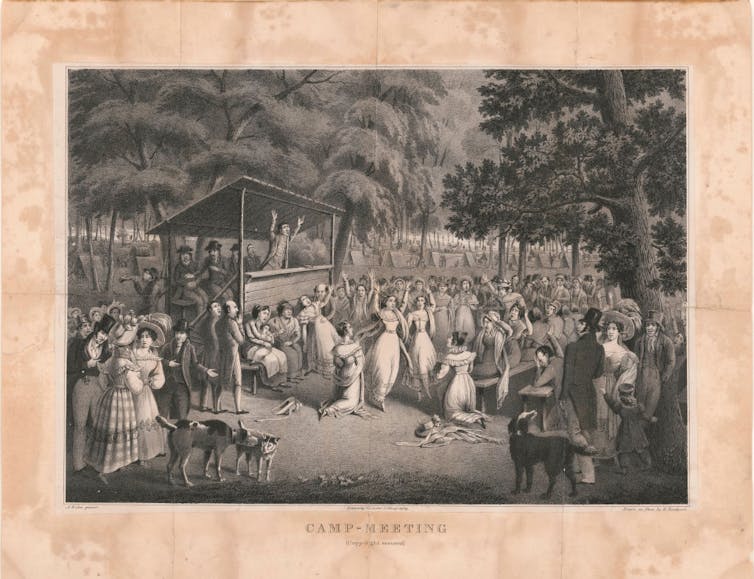

To do so navvies worked in geographical and social isolation; crude, muck-caked men on a helix spiralling down from prejudice [4/5] to more isolation, isolation to more prejudice. Eighty per cent were English, most of their work was in England, yet they lived like aliens in their own country, often outside its laws, usually outside its national sense of community. They were their own country's non-belongers. They belonged to themselves only tenuously. Mostly they lived apart in navvy settlements. New habits of life, thought, dress, speech, and a tightening of the ring against outsiders came out of their isolation. Their own countrymen were terrified of them, and despised them. Heavy drinking was normal, death by alcohol common. Drink was a common cause of riot, along with an unhesitating hatred for their own Irish minority. Their accident and death rates were higher than any other group in Britain, including colliers, including soldiers fighting nineteenth-century wars. Often they were nameless, known to each other only at second-hand by nickname. They were a homeless, wandering itinerant people belonging nowhere except to the island as a whole.

They survived the Great War as a separate community, but not for long. Nawying was killed by a lack of large scale public works (worsened by the Slump), by bureaucracy and by the petrol engine. Probably in that order. By the mid-1950s they were quietly ending as a recognisable separate community. Individuals did live and work on. Their descendants still do (at their height, just before the Great War, there may have been as many as a hundred and seventy thousand of them).

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

navy, navvies, Canada, England, canal, Great-Lakes, CPR, labor, labour, labourers, labor-history, labour-history, working-class,