The Conversation

November 21, 2024

Universe (Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, CC BY)

Physicists have long grappled with the question of why the universe was able to support the evolution of intelligent life. The values of the many forces and particles, represented by some 30 so-called fundamental constants, all seem to line up perfectly to enable it.

Take gravity. If it were much weaker, matter would struggle to clump together to form stars, planets and living beings. And if it were stronger, that would also create problems. Why are we so lucky?

Research that I recently published with my colleagues John Peacock and Lucas Lombriser now suggests that our universe may not be optimally tailored for life. In fact, we may not be inhabiting the most likely of possible universes.

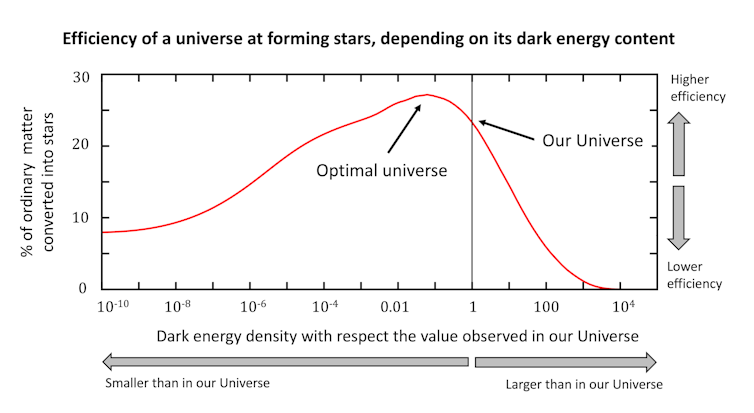

We particularly studied how the emergence of intelligent life is affected by the density of “dark energy” in the universe. This manifests as a mysterious force that speeds up the expansion of the universe, but we do not know what it is.

The good news is that we can still measure it. The bad news is that the observed value is way smaller than what we would expect from theory. This puzzle is one of the biggest open questions in cosmology, and was a primary motivation for our research.

We tested whether “anthropic reasoning” may offer a suitable answer. Anthropic reasoning is the idea that we can infer properties of our universe from the fact that we, humans, exist. In the late 80s, physics Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg discussed a possible anthropic solution for the observed value of the dark energy density.

Weinberg reasoned that a larger dark energy density would speed up the universe’s expansion. This would counteract gravity’s effort to clump matter together and form galaxies. Fewer galaxies means fewer stars in the universe. Stars are essential for the emergence of life as we know it, so too much dark energy would suppress the odds of intelligent life such as humans appearing.

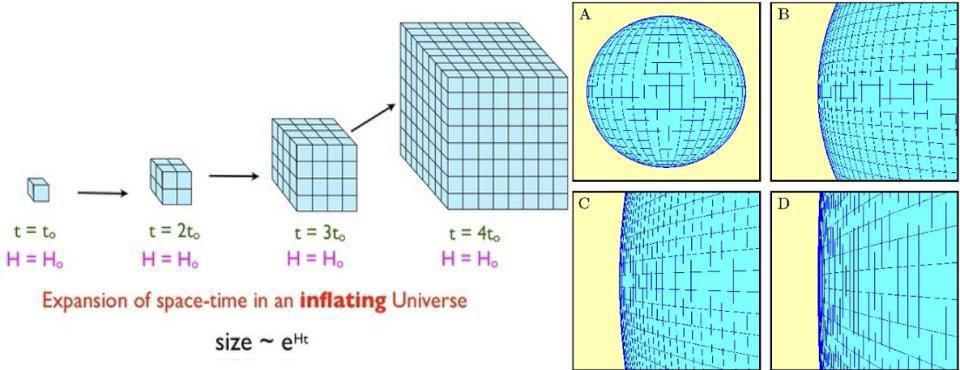

Weinberg then considered a “multiverse” of different possible universes, each with a different dark energy content. Such a scenario follows from some theories of cosmic inflation, a period of accelerated expansion occurring early in the universe’s history.

Weinberg proposed that only a tiny fraction of the universes within the multiverse, whether real or hypothetical, would have a sufficiently small dark energy density to enable galaxies, stars and, ultimately, intelligent life, to appear. This would explain why we observe a small dark energy density – despite our theories suggesting it should be much larger – we simply could not exist otherwise.

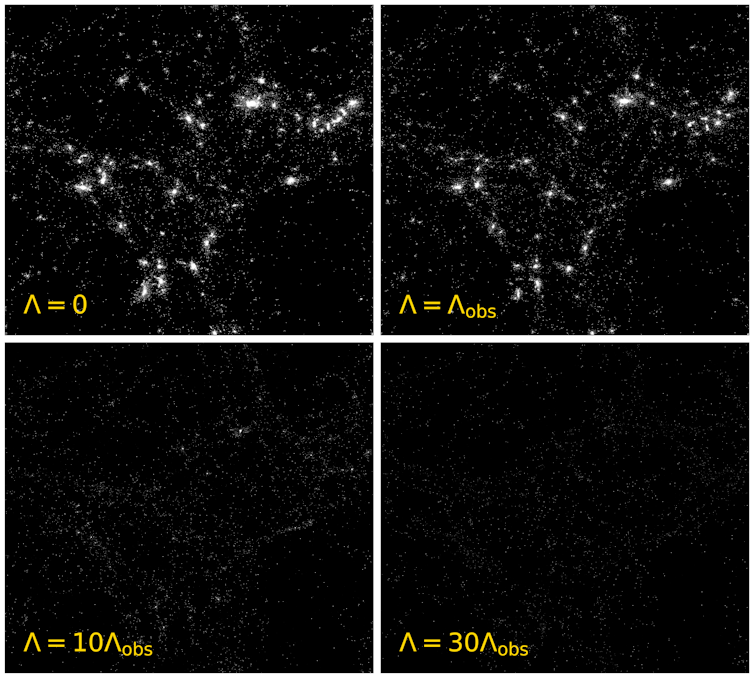

Number of stars (white) produced in universes with different dark energy densities. Clockwise from the upper-left panel: no dark energy, same dark energy density as in our universe, 30 and 10 times the dark energy density in our universe. Credit: Courtesy of Oscar Veenema, former undergraduate student at Durham University, now PhD student at Oxford University, CC BY-SA

A potential pitfall in Weinberg’s reasoning is the assumption that the fraction of matter in the universe that ends up in galaxies is proportional to the number of stars formed. Some 35 years later, we know that it is not that simple. Our research then aimed at testing Weinberg’s anthropic argument with a more realistic star formation model.

Counting stars

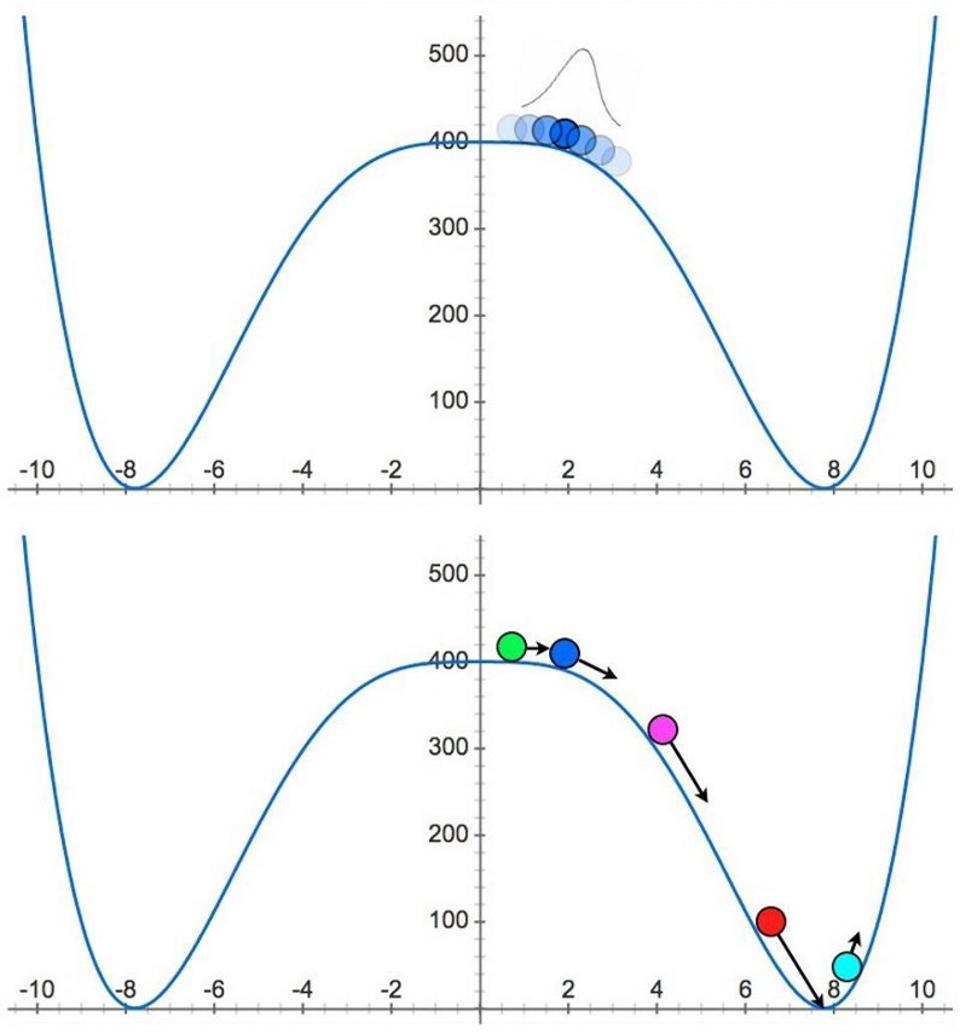

Our goal was to determine the number of stars formed over the entire history of a universe with a given dark energy density. This boils down to a counting exercise.

First, we picked a dark energy density between zero and 100,000 times the observed value. Depending on the amount, gravity can hold matter together more or less easily, determining how galaxies can form.

Next, we estimated the yearly amount of stars formed within galaxies over time. This followed from the balance between the amount of cool gas that can fuel star formation, and the opposing action of galactic outflows that heat up and push gas outside galaxies.

We then determined the fraction of ordinary matter that was converted into stars over the entire lifetime (past and future) of a certain universe model. This number expressed the efficiency of that universe at producing stars.

Credit: Image readapted from D. Sorini, J. A. Peacock, L. Lombriser, in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 535, Issue 2, Pages 1449–1474. Source: https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stae2236, CC BY-SA

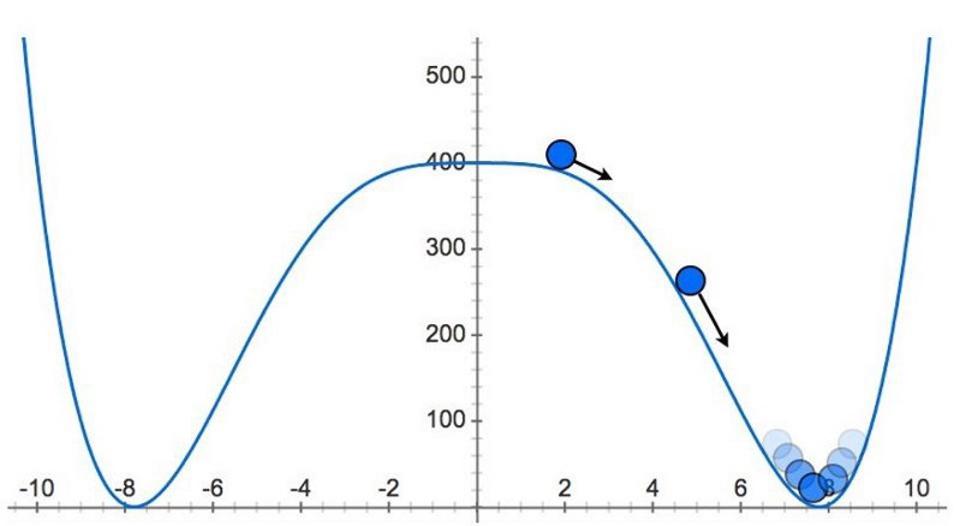

We then assumed that the likelihood of generating intelligent life in a universe is proportional to its star formation efficiency. As the figure above shows, this suggests that the most hospitable universe contains about one-tenth of the dark energy density observed in our universe.

Our universe is thus not too far from the most favourable possible for life. But it also isn’t the most ideal.

But to validate Weinberg’s anthropic reasoning, we should imagine picking a random intelligent life form in the multiverse, and ask them what dark energy density they observe.

We found that 99.5% of them would experience a larger dark energy density than observed in our universe. In other words, it looks like we inhabit a rare and unusual universe within the multiverse.

This does not contradict the fact that universes with more dark energy would suppress star formation, hence reducing the chances of forming intelligent life.

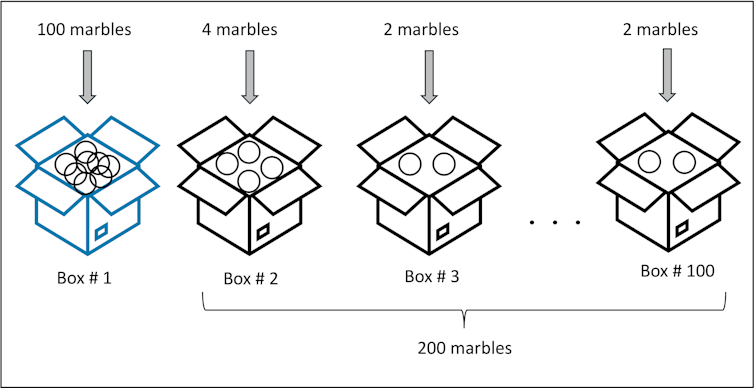

Marbles in boxes. CC BY-SA

By analogy, suppose we want to sort 300 marbles into 100 boxes. Each box represents a universe, and each marble an intelligent observer. Let us put 100 marbles in box number one, four in box number two and then two marbles in all other boxes. Clearly, the first box contains the single largest number of marbles. But if we pick one marble at random from all boxes, it is more likely to come from a box other than number one.

Likewise, universes with little dark energy are individually more hospitable for life. But life, although more unlikely, can still spawn in the many possible universes with abundant dark energy too – there will still be a few stars in them. Our calculation finds that most observers among all universes will experience a higher dark energy density than is measured in our universe.

Also, we found that the most typical observer would measure a value about 500 times larger than in our universe.

Where does that leave us?

In conclusion, our results challenge the anthropic argument that our existence explains why we have such a low value of dark energy. We could have more easily found ourselves in a universe with a larger dark energy density.

Anthropic reasoning may still be salvaged if we adopt more complex multiverse models. For example, we could allow for the amount of both dark energy and ordinary matter to vary across different universes. Perhaps, the reduced spawning of intelligent life due to a higher dark energy density might be compensated by a higher density of ordinary matter.

In any case, our findings warn us against a simplistic application of anthropic arguments. This makes the dark energy problem even harder to grapple with.

What should we cosmologists do now? Roll up our sleeves and think harder. Only time will tell how we solve the puzzle. However we will do it, I am sure it will be incredibly exciting.

Daniele Sorini, Post Doctoral Research Associate in Cosmology, Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

By AFP

November 21, 2024

The image of the massive star, which is encircled by a mysterious "egg-shaped cocoon" - Copyright AFP Andrej ISAKOVIC

Scientists said Thursday they have taken the first ever close-up image of a star outside of the Milky Way, capturing a blurry shot of a dying behemoth 2,000 times bigger than the Sun.

Roughly 160,000 light years from Earth, the star WOH G64 sits in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of our home Milky Way.

It is a red supergiant, which is the largest type of star in the universe because they expand into space as they near their explosive deaths.

The image was captured by a team of researchers using a new instrument of the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile.

Keiichi Ohnaka, an astrophysicist at Chile’s Andres Bello National University, said that “for the first time, we have succeeded in taking a zoomed-in image of a dying star”.

The image shows the bright if blurry yellow star enclosed inside an oval outline.

“We discovered an egg-shaped cocoon closely surrounding the star,” Ohnaka said in a statement.

“We are excited because this may be related to the drastic ejection of material from the dying star before a supernova explosion,” added the lead author of a study published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

– ‘Witness a star’s life in real time’ –

Ohnaka’s team has been watching the star for some time.

In 2005 and 2007 they used the Very Large Telescope’s interferometer, which combined the light from two telescopes, to learn more about the star.

But capturing an image remained out of reach until a new instrument called GRAVITY — which combines the light of four telescopes — recently came online.

When they compared all their observations, the astronomers were surprised to find that the star had dimmed over the last decade.

“The star has been experiencing a significant change in the last 10 years, providing us with a rare opportunity to witness a star’s life in real time,” said study co-author Gerd Weigelt of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy.

Red supergiants — such as Betelgeuse in the Orion constellation — are “one of the most extreme of its kind, and any drastic change may bring it closer to an explosive end,” added study co-author Jacco van Loon of Keele University in the UK.

In their final stages of life, before they go supernova, red supergiants shed their outer layers of gas and dust in a process that can last thousands of years.

It could be this expelled material that is making the star appear dimmer, the scientists said.

This could also explain the strange shape of the dust cocoon that surrounds the star.

Another explanation for the egg-shaped cocoon could be that there is another star hidden somewhere inside that has not yet been discovered.

"He said to me 'I hope a rocket comes and I can go to the Moon'. He didn't realise that the rocket would come and tear him up into pieces," says mother of Abdul Aziz, 7, who was killed by Israel along with his brother Hamza, 5 and sister Laila, 3.

AA

Relatives of the Palestinians who were killed in an attack on Al Mawasi area of Khan Younis mourn as dead bodies were taken from the Nasser Hospital for burial in Khan Yunis, Gaza on November 21, 2024. / Photo: AA

As Areej al-Qadi tearfully kissed the bodies of her three young children killed by Israel in an air strike in Gaza, another mourner lashed out at the United States and Arab leaders for not ending the genocide.

Palestinians in Gaza attending one funeral after another after more than a year of Israeli genocide feel abandoned and angry that their pleas for help have gone largely unanswered.

Qadi said her son Abdul Aziz, 7, killed by Israel along with his brother Hamza, 5 and sister Laila, 3, while they played outside in the southern Gaza city of Khan Younis, had wanted to be an astronaut.

"He said to me 'I hope a rocket comes and I can go to the Moon'. He didn't realise that the rocket would come and tear him up into pieces," she said.

"What right does America have, talking about democracy, justice and equality? said displaced mourner Ra'fat al-Shaer. "Also a message to the Arab world, to the heads of the Arab nations. How long will this continue?"

Arab countries have not backed their own calls for an end to the suffering of fellow-Muslims with any threats to end diplomatic agreements with Israel despite the killings of tens of thousands of civilians.

Reuters

Mourners gather next to the bodies of Palestinian children killed by Israel in a strike, during a funeral in Khan Younis in southern Gaza, on November 21, 2024.

'They were all martyred'

Israel has killed more than 44,000 people, wounded more than 104,000 and turned Gaza, one of the world's most densely populated places, into a wasteland of crushed cement and twisted metal.

Most of Gaza's population of 2.4 million people has been displaced and the enclave is at risk of famine, more than a year into Israel's genocide.

Many analysts say the reported death toll is a conservative estimate.

A letter to US President Joe Biden from a group of almost 100 American doctors who served in Gaza estimated a death toll of more than 118,000 in October 2024. And according to the UK medical journal The Lancet, the death toll could be more than 180,000.

People like Mahmoud Bin Hassan al-Thalatha, the father of the three children he said were killed along with other innocent people by Israel on a bustling street, say their only recourse is prayer.

"My children were martyred, the people walking were martyred, and the stall vendor was martyred while he was sitting down, they were all martyred. May God have mercy on them."

SOURCE: Reuters TRT World

By Abigail Gamble

November 21, 2024

Katanya Kuntz is a a quantum physicist and CEO and Co-founder of Qubo Consulting Corp. — Photo by Jennifer Friesen, Digital Journal

“Imagine a rat’s maze,” says Katanya Kuntz, a quantum physicist, CEO and co-founder of Qubo Consulting Corp.

She’s explaining how quantum technology works, during an interview with Digital Journal at Calgary Innovation Week.

You’ve got a rat at one end of the maze, and cheese at the other end. A classic computer is going to test out one path at a time, to figure out which path will get them to the cheese.

“But a quantum computer can try all possibilities simultaneously at once, and then find the path,” she said.

Which means, it figures out the best path much more quickly. And that’s thanks to quantum physics.

Here’s how quantum physics and technology work:

“We’ve had quantum physics for more than 100 years,” Kuntz explains. It’s the study of the microscopic building blocks of pretty much everything in the universe — like atoms. And they have different, rather wacky rules that we’re not used to experiencing in everyday life.

Some of what we understand about these building blocks or particles (their principles or rules) has been applied to what were called Quantum 1.0 technologies for a while, says Kuntz.

Essentially, everyday tools like lasers, LED lights, electronics, MRI and x-ray machines are created by applying the foundational principles of quantum physics to a technological process.

To return to the rat maze analogy…

In quantum physics, one of the “basic” rules is that a particle can exist in multiple places, simultaneously.

A particle doesn’t have a fixed location until we look at it. This happens because particles behave like waves of probability rather than fixed objects. Until we observe or measure a particle, it’s in a state of uncertainty, where all possible outcomes coexist.

So a quantum computer can explore every different maze path that’s possible, all at the same time.

Cool, huh?

It gets cooler though, because these days, scientists are working on technologies that use the more complicated quantum principle of entanglement to create “quantum networks” or a “quantum Internet” that will enable next-level data encryption. It’s Quantum 2.0.

How Quantum 2.0 is going to protect our data so it’s unhackable

An exciting example of Quantum 2.0 technology is Canada’s first quantum communication satellite that’s set to launch in 2025 or 2026, which will help secure our data in a whole new way, says Kuntz.

In addition to her role at Qubo, Kuntz is the science team coordinator for this mission, which is called the Quantum EncrYption and Science Satellite (QEYSSat), and is owned by the Canadian Space Agency.

What’s the satellite going to do exactly?

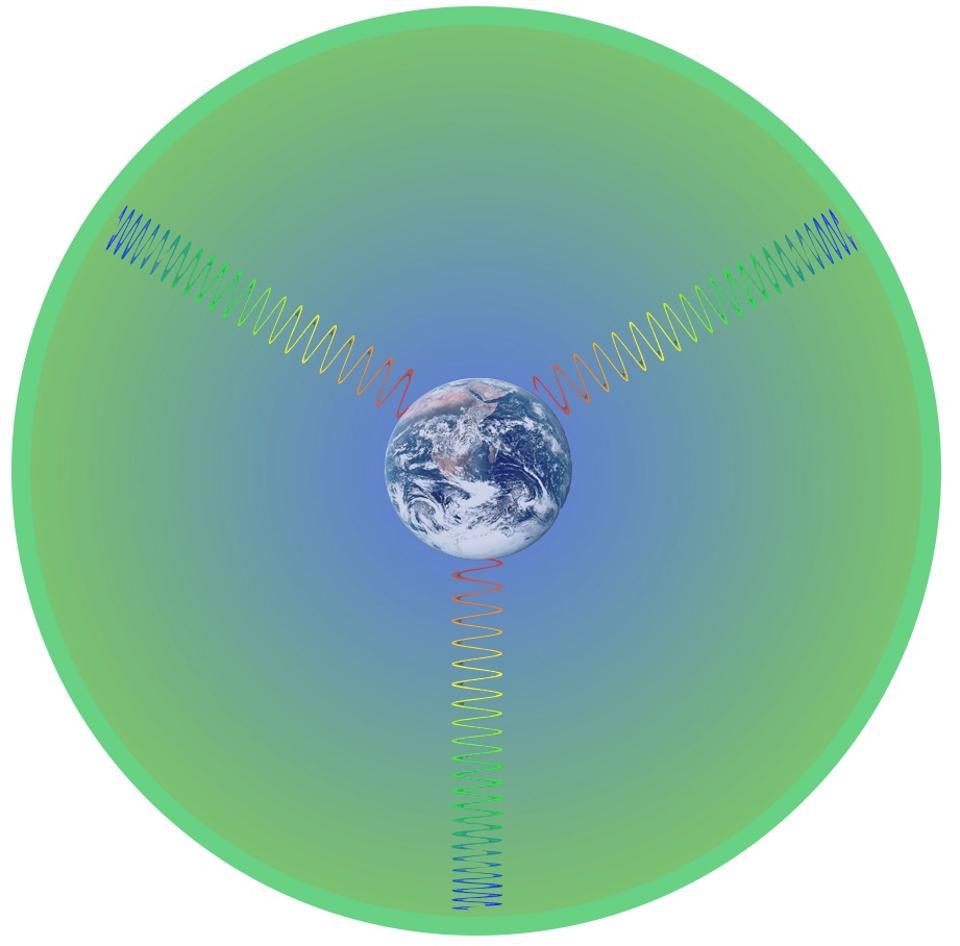

The QEYSSat science team is going to beam a laser up from the Earth to communicate with it.

“So there’s a ground station in Waterloo, Ontario,” Kuntz explains, “It’s literally a telescope … we’re going to shoot a laser up.” And this will be a “quantum uplink” sending particles of light — called photons — up from the ground to space.

Quantum communication systems are sent to space because satellites allow secure communication over long distances, something that’s hard to achieve on Earth due to interference and the limited range of ground-based fibre systems.

These photon signals can be used to encode and encrypt everything from online banking to sensitive transaction records to private government data, and are much, much more secure than any of the other encryption technologies we use today.

“With quantum, you can actually encrypt the information securely. So it’s theoretically 100% secure,” explains Kuntz.

And this level of encryption is increasingly necessary as hacking and ransomware threats become a bigger concern, she says.

“Calgary’s Public Library system got hacked about a month ago and was held hostage, and they still don’t have internet, computers, printers, anything electronic. There’s literally a sign when you walk into the public libraries here that says, ‘no technology.’ And you can take out books, but you can’t return books because they can’t check anything.”

How and why we need quantum satellite encryption:

When you encode information on the individual photons, if a hacker is trying to access your data, it will affect the light stream, and you’ll know because you’re monitoring that channel, says Kuntz.

“This is to everyone’s benefit,” she says and is part of the Canadian government’s quantum strategy, prepping for the day when the first quantum computers come online. This could happen in the next five to 15 years, says Kuntz.

“There’s around 20 countries already that have quantum satellite missions, so we’re not the first,” she says. But the value of having our own in Canada is to establish our own secure quantum network.

“So it’s our national sovereignty to have our own quantum Internet. It protects our own public information.”

Everyone else needs to prepare for our quantum future too

It’s not just governments who need to prepare for the quantum future, says Kuntz. Businesses and organizations can (and probably should) start looking now for quantum solutions to their problems.

And by problems, she means almost any challenge that includes a lot of complex variables.

For instance: “There are cities that are using quantum optimization algorithms, like Tokyo, to improve their transportation and waste management,” Kuntz says.

Some of the complex challenges quantum can help navigate include:

“If there’s events in the city, how is that going to affect the waste management? If there’s [extra] traffic flow, if there’s [unexpected] weather events, if there’s suddenly a snow dump, that’s going to really affect your routes, and maybe your garbage trucks won’t get to all their stops.”

Quantum tools can help provide solutions in situations like these, that are faster (like our rat to cheese scenario) and ensure the data involved is more secure (with next-level encryptions).

The speed and security of quantum can be used to improve the efficiency of every sector from finance, to aviation to agriculture and manufacturing, Kuntz says. “It’s not just one industry. This is touching every single industry in the world.”

She also notes that companies and organizations alike need to be prepared for when quantum computers come online, because they’ll be able to hack anything that isn’t quantum encrypted.

“Elect somebody in your company to be your technology evangelist, and have a small budget for their training.” Once they understand quantum a little better, Kuntz recommends sending them off to find people and tools who can help do a “cryptographic inventory” of your assets.

“Engage with a quantum company and start exploring,” she says.

Written By Abigail Gamble

Abigail is a writer, editor, journalist and content strategist based in Toronto and El Salvador.