Amid COVID-19 pandemic, deadly disease strikes rabbit populations

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

image:

Dr. Leif Andersson, professor at Uppsala University and another senior author of the study.

Credit: Mikael Wallerstedt

view moreCredit: Mikael Wallerstedt

How do rabbits go from fluffy pets to marauding invaders? Rabbits have colonized countries worldwide, often with dire economic and ecological consequences, but their secret has until now been a mystery. In a new study published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, an international consortium led by scientists from BIOPOLIS-CIBIO (Portugal) and Uppsala University (Sweden) sequenced the genomes of nearly 300 rabbits from across three continents to unveil the key genetic changes that make these animals master colonizers.

Throughout history, people have taken animals under their care. Your dear pet - furry kitten, loyal dog, or colorful goldfish - is just part of an amazing variety of domestic forms. “Some changed so much from their wild ancestors, it is difficult to imagine they are related, like chihuahuas that descend from wolves” explains Dr Pedro Andrade, a researcher at BIOPOLIS-CIBIO and first author of the study. “Changes are often so drastic, that if you put your pet back in the wilderness, it will be very challenging for it to survive”.

But sometimes, they do rise to the challenge. When they do, we call them ferals, populations of a once domestic species that successfully readapted to the wild. Rabbits are a classic example. Through frequent and independent releases, rabbits have colonized locations worldwide. But despite years of research, a central question has eluded scientists: how can a domestic animal, optimized for thousands of years to live in captivity, not only survive but thrive when returned to the wild?

“In a previous study by our team, which looked at the colonization of Australia by rabbits, we found that multiple releases of domestic rabbits had taken place for several decades before a single introduction of 24 rabbits with wild ancestry in 1859, by Englishman Thomas Austin, triggered the explosive population growth of rabbits which caused one of the largest environmental disasters in history” says Dr. Joel Alves, a researcher at BIOPOLIS-CIBIO and the University of Oxford.

Could this be the key to explaining why rabbits so frequently establish these feral populations? To answer this, the international team of researchers sequenced the genomes of nearly 300 rabbits, including six feral populations from three continents – Europe, South America, and Oceania – as well as domestic and wild rabbits from the native range in Southwest Europe. Armed with this treasure trove of information, the largest genetic dataset of rabbits ever produced, researchers could now understand what makes these introduced rabbits unique.

“Domestic rabbits are so common, that our initial expectation was that these feral populations would be composed of domestic rabbits that somehow managed to re-adapt to the wild, but our findings point to a more complex scenario” explains Dr. Miguel Carneiro, one of the senior authors of the study. According to him, “despite looking at six largely independent colonizations, all these feral rabbits share a mixed domestic and wild origin.”

The team found that during re-adaptation to the wild, genetic variants linked to domestication are often eliminated because they are often deleterious in the wild making animals more vulnerable to predation a pattern that is more striking depending on how extreme the trait had become during domestication. “In these feral populations, you will typically not see an albino, or a fully black rabbit, even if these fancy coat colors are very common in domestic rabbits. However, you may very well encounter rabbits that carry the mutation for diluted coat color, a domestic variant that has minimal effect on camouflage.” adds Dr. Leif Andersson, professor at Uppsala University and another senior author of the study, who continues “This is a concrete example of natural selection in action”.

This purging of domestic traits didn’t just target fancy coat colors. The team found evidence for strong natural selection operating on genes linked to behavior and the development of the nervous system. “Tameness is crucial for domestic animals to live close to humans, but it will not help a rabbit that finds itself back in the wild survive, so natural selection removes the genetic variants linked to tameness” explains Dr Andrade.

The study has implications for understanding evolution and will be closely followed by lawmakers and practitioners on the frontlines of conservation. Feral rabbits often turn into invasive pests causing hundreds of millions of dollars in damages, and other domestic-turned-wild animals cause similar problems, like feral pigs or feral cats. “The best strategy to mitigate the impacts of invasive species is to prevent them from being introduced in the first place, so we hope our study provides important evidence to help evaluate and identify future invasion risks” concludes Dr. Carneiro.

Nature

Observational study

Animals

Selection against domestication alleles in introduced rabbit populations

Edmonton's syphilitic cemetery bunnies killed off by different rare rabbit disease

A fluffle of feral cemetery rabbits at a northwest Edmonton cemetery, plagued by a syphilis outbreak in 2020, has been wiped out by a different and rare illness.

Rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) was discovered in three bunnies living in the colony at and around Holy Cross Cemetery in September, according to a memo from the Alberta government. By the end of September about 50 had died or disappeared

Very few, if any, are still alive.

“It was a very hot virus that rapidly ran through the colony and killed essentially all the feral domestic rabbits,” Margo Pybus, University of Alberta professor and wildlife disease expert, said in an email.

This disease is highly infectious with a rapid onset, and is almost always fatal in European rabbits, of which pet rabbits are descendants. It causes organ damage and internal bleeding. In some places it has spread to wildlife.

Before it was decimated, the libidinous fluffle of feral domestic rabbits lived at the cemetery and surrounding areas for about 30 years.

Klack’s group began capturing bunnies with syphilis symptoms — including fur loss, and crusting or sores on the eyes, mouth and genitals — in the summer of 2020 with the cemetery’s permission. But many rabbits were much sicker than expected, so rescuers were allowed to take any they could find.

Of about 200 rescued Klack said only 130 survived.

“Every rabbit we caught ended up being just overloaded with normally two to three different types of worms and parasites along with the syphilis,” they said in a recent interview.

Many were malnourished and had reproductive cancers, they said.

“A lot of volunteers got really burnt out because the rabbits they were rescuing were dying three days later. There was literally nothing we could do even with the best vet care,” they said. “I kept joking that my backyard is just one giant graveyard.”

The rabbits, and volunteers, also had to deal with hungry predators: “I had a volunteer chased out by coyotes. They were just feasting on those rabbits.”

With rescue efforts the colony began shrinking but numbers climbed again earlier this year, said Klack.

As they was preparing to resume rescues, a single case of RHD was confirmed in southern Alberta. Volunteers instead focused on getting rabbits already in care vaccinated.

While Klack had always hoped one day the colony would disappear — as domestic rabbits aren’t fit to live in the wild — they hoped it would be because the bunnies found new homes.

“I’m sad that I couldn’t rescue more, but knowing that there isn’t a giant colony out there that’s sick with syphilis and worms and all sorts of nasties, and that coyotes won’t be as big of a problem, that makes me happy,” they said. “It’s very much a multifaceted feeling.

“There’s not going to be more generations upon generations of rabbits just being born to suffer and die.”

Alberta’s first case of RHD was detected in Taber in March. The onset is quick and early symptoms can go undetected. Rabbits often die suddenly .

While the disease is new to Alberta, there were outbreaks in feral domestic rabbits in B.C. in 2018 and 2019.

Wild rabbits and hares have typically been immune to RHA, but a new strain killed some wildlife in the western United States and northern Mexico last year, according to an Alberta government handout. Alberta’s mountain cottontails, white-tailed jackrabbits, snowshoe hares and pikas may be at risk.

So far there isn’t evidence the disease spread to local wildlife.

But according to the BCSPCA, genetic sequencing of the case found in southern Alberta closely resembles the strain in the U.S. which has killed and infected wild animals.

“This has significant implications for wild rabbit welfare as well as ecosystem health, and also means that if the virus spreads to B.C., it could be virtually impossible to eliminate,” reads a release on the organization’s website this summer.

There is no treatment or cure for RHD. Vaccines aren’t approved in Canada but the B.C. government procured some using an emergency provision. Some Alberta veterinarians also ordered shipments from the B.C. government, but this program was recently discontinued.

Sorelle Saidman, president of Rabbitats Rescue Society in B.C., who helped co-ordinate efforts for some Alberta veterinarians to get vaccines said Alberta needs to make vaccines available. But, she said, many don’t care about rabbits.

“They’re not barking for attention, they’re not purring when they’re getting their pets … (but) they’re very affectionate, very sentient. They just need extra protection because they seem so unassuming.”

Request for information from the Alberta government about how the disease arrived, how many and which kinds of animals have been killed, and whether it is working to acquire RHD vaccines were not answered by deadline.

Rabbit virus has evolved to become more deadly, new research finds

AND AS THEY HAVE FOUND IN CALGARY

by Pennsylvania State University

A common misconception is that viruses become milder over time as they become endemic within a population. Yet new research, led by Penn State and the University of Sydney, reveals that a virus—called myxoma—that affects rabbits has become more deadly over time. The findings highlight the need for rigorous monitoring of human viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, monkeypox and polio, for increased virulence.

"During the COVID-19 pandemic, many people have incorrectly assumed that as the SARS-CoV-2 virus becomes endemic, it will also become milder," said Read.

"However, we know that the delta variant was more contagious and caused more severe illness than the original strain of the virus, and omicron is even more transmissible than delta. Our new research shows that a rabbit virus has evolved to become more deadly, and there is no reason why this couldn't happen with SARS-CoV-2 or other viruses that affect humans."

According to Read, myxoma was introduced to Australia in the early 1950s to quell an out-of-control non-native rabbit population. Known as "myxomytosis," the disease it caused resulted in puffy, fluid-filled skin lesions, swollen heads and eyelids, drooping ears and blocked airways, among other symptoms. The virus was so deadly that it killed an estimated 99.8 percent of the rabbits it infected within two weeks.

Over time, however, the virus became milder, killing only 60% of the rabbits it infected and taking longer to do so.

"Scientists at the time believed this outcome was inevitable," said Read. "What they called the 'law of declining virulence' suggested that viruses naturally become milder over time to ensure that they do not kill their hosts before they've had a chance to be transmitted to other individuals."

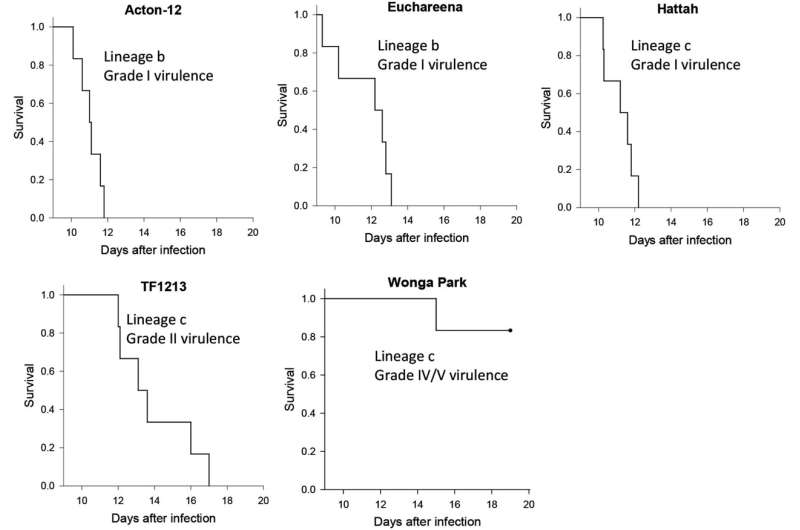

Yet, when Read and his team began to study the myxoma virus in rabbits in 2014, they found that the virus had regained the upper hand and was once again killing rabbits at a higher rate. In their most recent study, which published on Oct. 5 in the Journal of Virology, they examined several myxoma virus variants collected between 2012-2015 in the laboratory to determine their virulence. The team determined that the viruses fell into three lineages: a, b and c.

Interestingly, Read said, the rabbits in their study exhibited different symptoms than those induced by viruses collected in the first decades after the release.

"Instead of developing puffy, fluid-filled lesions, these rabbits developed flat lesions, suggesting a lack a reduced immune response," said Read.

"In addition, these rabbits had significantly more bacteria distributed throughout multiple tissues, which is also consistent with immunosuppression. We interpreted this 'amyxomatous' phenotype as an adaptation by the virus to overcome evolving resistance in the wild rabbit population."

Lineage c, however, produced a slightly different response in rabbits. Rabbits infected with lineage c had significantly more swelling at the base of the ears and around the eyelids, where mosquitoes typically bite. These areas also contained extremely high amounts of virus.

"Insect transmissibility is dependent on high amounts of virus being present in sites accessible to the vector," said Read. "We hypothesize that lineage c viruses are capable of enhanced dissemination to sites around the head where mosquitoes are more likely to feed and that they are able to suppress inflammatory responses at these sites, allowing persistent virus replication to high amounts."

Read said that the team's findings demonstrate that viruses do not always evolve to become milder.

"By definition an evolutionary arms race occurs when organisms develop adaptations and counter-adaptations against each other," said Read.

"With myxoma, the virus has developed new tricks, which are resulting in greater rabbit mortality. However, over time the rabbits will likely evolve resistance to these tricks. An analogous arms race may be occurring with SARS-CoV-2 and other human viruses as humans become more immune. This is why it's so important for vaccine manufacturers to keep up with the latest variants and for the public to stay up to date on their vaccines. Better still would be to develop a universal vaccine that would work against all variants and be effective for a longer period of time."

The research was published in Journal of Virology.

image:

When domesticated rabbit breeds return to the wild and feralise, they do not simply revert to their wild form – they experience distinct, novel anatomical changes.

view moreCredit: Michael SY Lee.

Originally bred for meat and fur, the European rabbit has become a successful invader worldwide. When domesticated breeds return to the wild and feralise, the rabbits do not simply revert to their wild form – they experience distinct, novel anatomical changes.

Associate Professor Emma Sherratt, from the University of Adelaide’s School of Biological Sciences, led a team of international experts to assess the body sizes and skull shapes of 912 wild, feral and domesticated rabbits to determine how feralisation affects the animal.

“Feralisation is the process by which domestic animals become established in an environment without purposeful assistance from humans,” says Associate Professor Sherratt, whose study was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society.

“While you might expect that a feral animal would revert to body types seen in wild populations, we found that feral rabbits’ body-size and skull-shape range is somewhere between wild and domestic rabbits, but also overlaps with them in large parts.

“Because the range is so variable and sometimes like neither wild nor domestic, feralisation in rabbits is not morphologically predictable if extrapolated from the wild or the domestic stock.”

Associate Professor Sherratt, who performed this study as part of her ARC Future Fellowship, says the greater diversity seen in the skull shape of feral rabbit populations could be related to changes in evolutionary pressures.

“Exposure to different environments and predators in introduced ranges may drive rabbit populations to evolve different traits that help them survive in novel environments, as has been shown in other species.

“Alternatively, rabbits may be able to express more trait plasticity in environments with fewer evolutionary pressures.

“In particular, relaxed functional demands in habitats that are free of large predators, such as Australia and New Zealand, might drive body size variation, which we know drives cranial shape variation in introduced rabbits.” she says.

Associate Professor Sherratt plans to follow up this research by looking into what environmental factors drive the observed variation in body size and skull shape of Australia’s feral rabbits.

“We found Australian feral rabbits are quite a lot larger than European rabbits. We intend to find out why,” she says.

“And we focus on skull shape because it tells us how animals interact with their environment, from feeding, sensing and even how they move.

“Understanding how animals change when they become feral and invade new habitats helps us to predict what effect other invasive animals will have on our environment, and how we may mitigate their success.”

The University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia are joining forces to become Australia’s new major university – Adelaide University. Building on the strengths, legacies and resources of two leading universities, Adelaide University will deliver globally relevant research at scale, innovative, industry-informed teaching and an outstanding student experience. Adelaide University will open its doors in January 2026. Find out more on the Adelaide University website.