Sikhs’ Sixth Guru Hargobind Ji’s Doctrine Of Miri-Piri: Champion Of Justice And Equality – OpEd

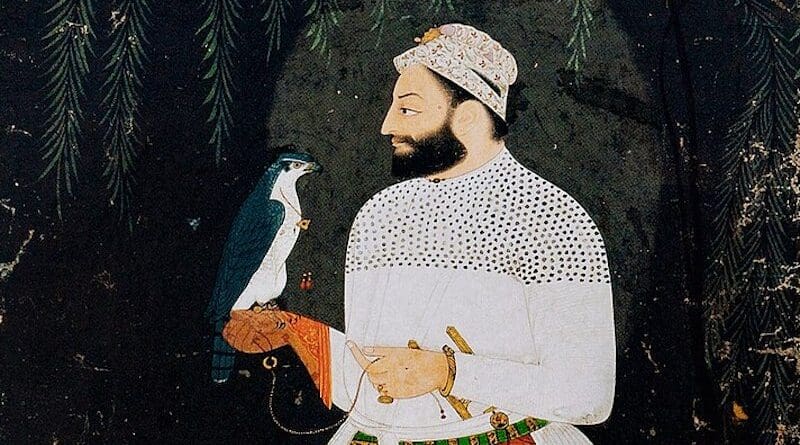

Sikh Guru Hargobind Ji. Credit: Unknown author, Wikipedia Commons

Guru Hargobind Ji, the sixth Guru of the Sikhs, introduced a transformative vision to Sikhism that fortified its foundations in the face of tyranny and injustice.

Being the son of Guru Arjan Dev Ji, the first martyr in Sikh history, Guru Hargobind was profoundly influenced by a pressing imperative to safeguard Sikh community and uphold the fundamental principles of Sikhism, which include compassion, equality and justice. Guru Hargobind Ji established a robust Sikh identity through his principles, policies, and institutions, enabling it to endure oppression while championing dignity and human rights.

Sikhism: Foundational Tenets

Sikhism represents a significant spiritual and philosophical traditions which were originated in Punjab within the Indian subcontinent in the late 15th century. Sikhism, a faith that has arisen in comparatively modern times among the world’s principal religions, is remarkable for having attracted a global following of around 25 to 30 million adherents. The Sikh faith originates from the profound teachings of Guru Nanak (1469–1539), the first of the ten Sikh gurus, whose insights were further developed by his revered successors. Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth guru, declared the Guru Granth Sahib to be the eternal guru, thus bringing an end to the succession of human gurus and establishing the scripture as the supreme religious text for the Sikh community.

Sikhism emerged within a milieu characterized by significant religious persecution, particularly during the Mughal era, a period that saw the martyrdom of like Guru Arjan and Guru Tegh Bahadur. The events previously mentioned acted as a significant impetus for the formation of the Khalsa by Guru Gobind Singh in 1699, a revered congregation of “saint-soldiers” dedicated to the honorable mission of protecting religious liberty and the integrity of faith. The deep and complex tenets and rituals of Sikhism act as a wellspring of motivation and collective harmony for its followers.

The Sikh traditions posit that God is formless yet accessible; defined by fearlessness, free from adversaries, self-originating, and transcending the limitations of birth and time. The esteemed scripture, referred to as Sri Guru Granth Sahib, articulates the intricate essence of the Divine with remarkable profundity. This fundamental conviction in a singular God inherently leads to the essential principle of equality among all people, surpassing differences in race, religion, gender, and social status. Proponents of Sikhism assert that every person holds equal value in the eyes of the God; this sacred doctrine champions the equality of genders, the affluent and the impoverished, and the rights of individuals irrespective of racial distinctions. Thus, it is a fundamental principle of Sikhism that individuals from various faith traditions can achieve a connection with the Divine, as long as they sincerely follow the true path of their own beliefs.

The essential principles of Sikhism, as expressed in the revered Guru Granth Sahib, include a deep reverence for the One Creator (Ik Onkar), the intrinsic unity and equality of all people, the dedication to selfless service (Sevā), the steadfast quest for justice (Sarbat Da Bhala—the well-being of all), and a strong adherence to integrity in personal behavior. Sikhism upholds the principle of equality among all individuals, irrespective of their background or social standing. This message was imparted by all Gurus, who championed a society devoid of caste distinctions, where no individual held superiority over another and where the rights of others were to be respected and safeguarded. The Sikh Gurus championed the rights of every individual, irrespective of their religion, caste, gender, or race. They upheld the principle of liberty for everyone to exist unencumbered by excessive interference or limitations.

The relationship between the Sikhs and the Mughals experienced a significant transformation in 1606, marked by the martyrdom of Guru Arjan Dev Ji. The execution of the fifth Guru Arjan Dev, by Emperor Jahangir during his reign (1605-1627), signified the onset of a period characterized by the persecution of Sikhs, whose beliefs posed a challenge to the prevailing religious bigotry of the Empire. Guru Hargobind Ji was deeply influenced by the tragic martyrdom of Guru Arjun Dev Ji, which motivated him to adopt a proactive stance that transformed the community’s view on oppression. A notable shift from the nonviolent approaches of his predecessors, Guru Hargobind emphasized the importance of armed resistance upon recognizing that mere moral courage could not adequately protect the community. This adaptable approach not only safeguarded Sikhism but also positioned the community as a formidable defender of human rights and justice. This tradition was further reinforced by Guru Teg Bahadur, who gave his life to protect the Kashmiri Pundits from the persecution imposed by the Mughal regime.

The Sikh Gurus bequeathed a profound legacy to the followers, urging them to maintain elevated moral standards and to embrace personal sacrifice in the defense and preservation of these noble principles. Guru Arjan Dev, Guru Tegh Bahadur, and Guru Gobind Singh exemplify this principle remarkably who sacrificed for the larger interest of the followers. These sacrifices/martyrdoms exemplified the Sikhs’ capacity to confront oppression and tyranny with steadfast and resolute determination.

Guru Hargobind Sahib: Early Life

Guru Hargobind, born in Gurū kī Waḍālī on June 19, 1595, was the sole offspring of Guru Arjan, the fifth Guru of the Sikhs. Guru Hargobind was instructed in religious teachings by Bhai Gurdas and honed his skills in military swordsmanship and archery under the guidance of Baba Budda. During his formative years, he was deeply immersed in the hymns resonating within the Harmandir Sahib complex in Amritsar. On 25 May 1606, the fifth Guru, Arjan, designated his son Hargobind as his successor, instructing him to establish a military tradition aimed at safeguarding the Sikh religion and its adherents. On the 30 May, 1606, he faced arrest, endured torture, and ultimately met his demise at the hands of Mughal Emperor Jahangir. The succession ceremony of Guru Hargobind took place on 24 June, 1606, during which he donned two swords symbolizing his spiritual and temporal authority.

Relations Between Sikh Gurus and Mughals

The spiritual and socio-political impact of the Sikh religion in Mughal India transformed the dynamics between the Sikh Gurus and the Mughals, shifting it from a state of coexistence to one of conflicted ones. Guru Nanak, the first Sikh Guru, advocated for peace and spirituality while maintaining a stance of non-opposition towards Mughal governance. He stood against injustice, as evidenced by his reaction to Babur’s invasions. Given that Sikhism emerged as a devotional movement, Emperor Akbar exhibited a degree of tolerance towards its followers. The early Sikh Gurus successfully nurtured their community and identity within the framework of Akbar’s pluralistic approach. The circumstances underwent a significant transformation during the reign of Jahangir. Guru Arjan, the fifth Guru, ardently supported Prince Khusrau and steadfastly declined to alter Sikh scripture, a stance that ultimately culminated in his martyrdom. Following his martyrdom, Sikhism adopted a defensive stance in response to Mughal oppression. Guru Hargobind, the successor of Guru Arjan, adeptly intertwined spiritual guidance with a stance of political defiance. He urged Sikhs to take up arms for self-defense, confronting Mughal forces and solidifying the Sikh community as both a religious and political entity.

Guru Tegh Bahadur and his contemporaries opposed Mughal authority, particularly in response to Aurangzeb’s coercive conversion efforts. The execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur stands as a poignant testament to the Sikh commitment to religious freedom and the resistance against tyranny, particularly in his defense of Hindu rights. His martyrdom fortified the Sikhs’ determination to withstand persecution and uphold their autonomy.

The 10th Guru Gobind Singh established the Khalsa, a brotherhood of warriors committed to upholding justice and faith, thereby militarizing the Sikhs. The Khalsa valiantly resisted Mughal oppression through direct confrontations. The rebellion led by Banda Singh Bahadur established Sikh governance in Punjab, thereby laying the foundation for the Sikh Empire. The resilience of Guru Gobind Singh served as a profound source of inspiration. The interactions between Sikhs and Mughals significantly influenced Sikhism, establishing it as a movement characterized by justice, bravery, and self-determination, while simultaneously crafting the Sikh identity through spiritual practices and a steadfast opposition to injustice.

Guru Hargobind Sahib’s -Doctrine of Miri-Piri

Guru Hargobind Ji’s introduction of the concept of two swords (Miri-Piri) concept established the foundation of his leadership, providing a dual mandate that balanced temporal power with spiritual responsibilities. By wearing two swords, one representing Miri (temporal power) and the other Piri (spiritual authority), Guru Hargobind sent a clear message to both Sikhs and the ruling Mughals: spiritual principles alone were insufficient in a world that ignored moral persuasion and allowed oppression to thrive. Instead, a full and just life necessitated both spiritual discipline and a willingness to defend oneself and others. Guru Hargobind Ji instilled in Sikhs a sense of moral duty through Miri-Piri, teaching them that self-defense and protecting others were sacred responsibilities rather than acts of aggression. This vision inspired Sikhs to become Saint-Soldiers, people who combined spiritual knowledge and martial discipline. This dual role strengthened the Sikh community’s resistance to tyranny and provided an alternative social model in which spiritual progress coincided with active participation in worldly affairs.

In 1606, Guru Hargobind Ji founded the Akal Takht, or the “Throne of the Timeless One,” opposite the Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar. The Akal Takht emerged as the inaugural seat of sovereign, independent temporal authority in Sikhism, enabling the Guru to resolve temporal matters and issue hukamnamas (directives) for the Sikh followers. The Akal Takht, by creating an institution free from Mughal influence, emerged as a center for Sikh autonomy, representing a distinctive fusion of spiritual leadership and secular authority.

The Akal Takht exemplified Guru Hargobind Ji’s profound dedication to justice, liberty, and equality. He convened councils, rendered legal judgments, and guided Sikhs in social and military affairs. By aligning Sikh leadership with principles of justice and moral authority, the Akal Takht emerged as a symbol of resistance against oppression. The enduring significance of the Akal Takht in Sikhism highlights the persistent legacy of Guru Hargobind’s principles, positioning it as a bastion for the advocacy of the oppressed and marginalized.

The legacy of Guru Hargobind Ji as a champion of human rights and dignity is evident in his unwavering resistance to Mughal despotism. Throughout his tenure as Guru, he faced numerous Mughal assaults and invasions. Instead of yielding to oppression, Guru Hargobind organized and trained a military contingent, enabling the community to protect itself. This decision established a precedent for resistance against oppression, positioning the Sikh community as a potent symbol of resilience for other marginalized groups under Mughal rule.

Guru Hargobind conveyed that the struggle for justice and dignity is universal. He directed his adherents to perceive self-defense as an obligation rather than an individual entitlement. By fostering an ethos of seva (selfless service) within the Sikh community, he guaranteed that armed defense was utilized solely to protect the vulnerable and uphold justice, rather than for personal advantage. His actions reverberated among other marginalized groups throughout India, galvanizing a unified opposition to the Mughal Empire’s religious intolerance and political despotism.

Guru Hargobind Ji’s notable act of liberation involved the release of 52 Hindu kings from Gwalior Fort, an event now observed as Bandi Chhor Divas. Guru Hargobind’s spiritual influence was further intensified when he conditioned his release with the liberation of 52 kings who had been unjustly imprisoned by Emperor Jahangir with him. Bandi Chhor Divas is a lasting testament to Guru Hargobind’s commitment for the protection of justice and human rights. His actions went beyond personal liberation, emphasizing his dedication to liberation of others from the shackles of oppression. The Sikh tenets of universal brotherhood and the Guru’s doctrine of equality and justice were exemplified by this demonstration of moral fortitude and compassion. Bandi Chhor Divas is now observed not only as a Sikh festival, but also as a symbol of the triumph of truth over oppression, justice, and resistance.

Vision of an Egalitarian Society

In addition to his political and military endeavors, Guru Hargobind Ji pursued the traditions of establishment of langars community kitchens), where individuals from all castes and social standings shared meals. His focus on selfless service underscored the significance of altruism in enhancing societal welfare and guaranteeing equitable resource distribution. The egalitarian principles espoused by Guru Hargobind Ji stood in sharp opposition to the social hierarchies upheld by the ruling elite. Through the cultivation of a society that granted respect and dignity to every individual, he confronted the dominant conventions of his era and established the groundwork for a community rooted in equality, compassion, and solidarity. This embrace of diversity is fundamental to Sikh identity, emphasizing the belief that spirituality is deeply connected to social responsibility and the protection of human rights.

The life and leadership of Guru Hargobind Ji catalyzed a transformation within Sikhism, evolving it from a spiritual community into a vigorous advocate for justice. The introduction of Miri-Piri transformed the Sikh identity, inspiring Sikhs to seek both spiritual enlightenment and active participation in worldly matters. This dual function fortified the community’s determination, empowering it to withstand oppression and safeguard the marginalized. The Guru’s focus on self-defense as a revered obligation, coupled with his founding of the Akal Takht, equipped Sikhs with the necessary institutional and ideological structures to uphold their resistance against oppression. The policies he implemented had a significant impact on later Sikh Gurus, especially Guru Gobind Singh Ji, who codified the Sikh martial tradition through the creation of the Khalsa. The principles imparted by Guru Hargobind to his disciples remain relevant, inspiring Sikhs across the globe to exemplify compassion, bravery, and fortitude.

Conclusion

The profound leadership of Guru Hargobind Ji remains a guiding force in the Sikh tradition, fostering a deep dedication to justice, equality, and the protection of human rights. Through the promotion of a harmonious existence characterized by Miri-Piri, the defense of human dignity, and the advancement of egalitarian principles, he established the groundwork for a robust Sikh community ready to face oppression in its various manifestations. His teachings serve as a reminder that spirituality is an active endeavor, intricately linked to the principles of justice and compassion in our engagement with the world. The legacy of Guru Hargobind as a champion of freedom, advocate for social change, and protector of rights surpasses his era, providing an enduring framework for addressing injustice and promoting a society that embraces inclusivity. In a society that persistently confronts challenges of injustice and disparity, the life and teachings of Guru Hargobind serve as a profound reminder of the lasting significance of bravery, empathy, and an unwavering dedication to the dignity of all individuals.

Dr. Bawa Singh

Prof. (Dr.) Bawa Singh has been teaching at the Department of South and Central Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Central University of Punjab. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from Panjab University. He has extensive teaching and research experiences and has held various academic roles. Prof. Singh has held key administrative positions, including Head of the Department and Dean of the School of International Studies. His research interests include the geopolitics of South and Central Asia, Indian foreign policy, regional cooperation, and global health diplomacy. He has led significant research projects, including an ICSSR-funded study on SAARC's geostrategic and geo-economic role. Singh has published 61 papers, 15 book chapters, 100 commentaries, and two books published by Routledge and Springer Nature.