Thomas Hobbes by John Michael Wright

November 26, 2025

By Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic

With his views within the history of political philosophy, the English political theorist Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) became a classic representative of the school of English empiricism. He built a comprehensive political science system based on the basic thesis that in the real world, there are only individual material bodies. With this view, Hobbes began a war against the prejudices of medieval realism, for which concepts were the true reality, while things were merely derived from them. It is important to note that Hobbes believed that there were three types of individual bodies: 1) Natural bodies (i.e. bodies of nature itself that do not depend on man and his activities); 2) Man (both a body of nature and the creator of an artificial, i.e. unnatural, body); and 3) The State (an artificial body as a product of man’s activities).

Hobbes’s most important political science work is Leviathan (1651) [full and original title: Leviathan or the matter, form and authority of government, London] in which he elaborates his philosophical views on the third body, i.e., the state, of course, in the context of the time in which he lived and witnessed. In short, in this work, Hobbes elaborated on the view that the natural state of life of the human race is a war of all against all (bellum omnium contra omnes). According to him, this view is followed by a natural law that leads to the overcoming of such a state and the creation of the state (i.e. political organization) through a social contract between citizens and the government, but also a contract that finally recognizes the indivisible and unlimited power of the sovereign (king) in the polity (state organization) for the protection of citizens and their rights. In other words, citizens voluntarily give up a (large) part of their natural freedom, which they transfer to the state for the purpose of protecting themselves from external and internal enemies. This would be a political form of voluntary and contractual “escape from freedom” that was masterfully deciphered by the German philosopher Erich Fromm (1900–1980) in his eponymous work Escape from Freedom (1941), using the example of German society during the era of National Socialism.

The social and historical foundations of Hobbes’s political thought were the frequent civil wars in England, in which King Charles I Stuart (1625–1649) lost both his crown and his head (which was cut off with an axe), the emergence of two political currents in the Parliament of England, in fact later parties – the Tories (conservatives) and the Whigs (liberals), as well as the proclamation of the Commonwealth (i.e., a republic, or “welfare state”, 1649–1660) but with the dictator Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658), who from 1653 bore the title of “Protector” (“Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland”). At that time, English capitalist and even colonial-imperialist development required protection from an extremely strong and all-powerful state in the form of a monarchy, i.e., royal absolutist power.

Basically, Thomas Hobbes did not criticize the current socio-political system, but rather tried to consolidate it and strengthen it as much as possible so that the entire state with its citizens could function as well as possible and be as efficient as possible, which would be for the benefit of all citizens who first enter into a contract on bilateral relations among themselves and then with the state. Even from a European perspective (civil wars between Protestants and Catholics), given that an atmosphere of fear and personal insecurity prevailed throughout Western Europe, Hobbes desired peace, security, and the protection of private property, so that to this end he became a pronounced statist, i.e., a supporter of the strongest possible state power over individual citizens.

In the late European Renaissance and early modern period, the strengthening of monarchical power through the development of enlightened monarchical absolutism (despotism) was an expression of the need for social and state unity and harmonious functionality in order to avoid medieval political anarchy, polytheism, and powerlessness. When monarchical absolutism is emphasized, it is generally not because of the illusion of the divine rights of the ruler, but because of the practical conviction that strong political unity can only be achieved within the framework of enlightened absolutist monarchism. Thus, when Hobbes supports the centralist absolutism of the king, he does not do so because he believes in the divine rights of kings or in the divine character of the principle of legitimacy, but because he believes that the cohesion of society and national unity can primarily be achieved in this way. Hobbes believes in the natural egoism of the individual, and a natural consequence of this belief was the view that only a strong and unlimited (absolutist/despotic) central authority of a monarch is capable of restraining and overcoming the centripetal forces that lead to the disintegration of the social community and the dissolution of the state.

Leviathan (1651) – political system (state) according to the contractual state

It should be noted that the starting point of Thomas Hobbes’ political philosophy is the same as that of all other representatives of the so-called “natural law and social contract” school. Hobbes, like many others from the same school, reduces the individual man to the order in nature, and the civil state to the state of a contract between citizens and the state, but which is formed by subjects who, by the very contract with the state (monarch), should become citizens, thus freeing themselves from the position and role of medieval lawless subjects (i.e. those who had only obligations to the government but no rights in relation to the same government) at least according to the liberal political philosophy.

For Hobbes, the basis of human nature is egoism and not altruism, as well as the need for communal life, but not as some kind of drive for communal life (as in wild animals that live in packs), but a need out of purely egoistic interest. In other words, organized political society in the form of a state arises as a result of the fear of some individuals of others, and not as a result of some natural inclination of some individuals towards others. Therefore, the state is an imposed socio-political organization as a product of a rational view of life, i.e., survival, of the human community in order to preserve individual interests, including bare lives. In other words, Hobbes denied happiness and pleasure as elements of the natural state or order. On the contrary, for him, the natural state is dangerous for human existence because it is animalistically cruel and murderous. A state in which everyone wars against everyone. In a natural order that operates according to the (animal) laws of nature (the right of the stronger), the basis of inter-living relations is war based on force and deception.

The next important characteristic of the natural order is the absence of ownership of things and possessions in the sense of the absence of a clear demarcation of what is whose. In other words, everything belongs to everyone, and what is whose depends, at least for a while, on force, robbery, and coercion over others. For Hobbes, all human beings are equal both physically and intellectually, and everyone has a right to everything, striving to preserve this natural right. However, since at the same time they strive to achieve power or at least dominance over others, a war of all against all inevitably occurs, so that human life becomes unbearable. The stronger strive to become even stronger and more influential, and the weaker strive to find protection from the stronger in order to survive. On the one hand, man strives to preserve his natural freedom, but on the other hand, to gain power over others. For Hobbes, this is the dictate of the instinct for self-preservation (freedom + dominance). The human race has the same drive for all things, and therefore, all people want the same things. Therefore, all people are a constant source of danger, insecurity, and fear for others in the brutal drive for survival. Therefore, human existence is reduced to a war of all against all (man is a wolf to man).

For Hobbes, the fundamental natural law is therefore the law of egoism, which directs the human individual to preserve himself with minimal losses and maximum gains at the expense of others. Natural law (ius naturale) is, therefore, the instinct for self-preservation, i.e., the freedom for everyone to use their own strength and skill to preserve their existence. However, the fundamental meaning of the existence of the human individual is the search for security. Therefore, for Hobbes, only interest, and not altruism (the inclination of man to man), is the fundamental natural motive in the search for a way out of the state of nature because it is becoming unbearable. In other words, natural freedom is becoming an increasingly heavy burden on human shoulders that must be endured.

Hobbes opposed the teachings of Aristotle and Grotius that man himself originally has an urge to associate, i.e., a social instinct. Contrary to both of them, Hobbes believes that man is originally a completely egoistic being and possesses only one urge, which is the urge for self-preservation. This urge drives man to realize his needs, to seize as much as possible from what nature itself puts at his disposal and, in accordance with this urge, to expand the sphere of his individual power as much and as far as possible. However, according to the very logic of things, in this intention of his, man encounters resistance from other people who are guided by the same natural (innate) urge, i.e., aspirations, and thus competition, struggle, and war arise between members of the human race, which threaten the physical existence of people. Therefore, if man lives in a state of nature, he is confronted with the reality of the war of all against all, i.e. a war that is naturally caused by the need and strength of the individual and a war in which the eventual lack of physical strength, i.e. superiority, is replaced by cunning and deception according to the principle that the end justifies the means.

The state of nature does not allow human reason to do anything that can in any way physically endanger his own life, as well as to neglect what can best preserve it. Hobbes acknowledges that human nature is such that he is always in conflict with various passions and drives, among which the desire for power is predominant. However, by using reason, man realizes in practice natural laws, among which the basic aspiration for peace is (human personality = conflict of passions and reason). People, following reason and natural laws that strive for man to preserve and ensure peace by all available means, conclude a socially beneficial contract or agreement among themselves. On the basis of such a contract, people within the same living community living in the same living space unite with the aim of forming a stronger community with joint forces on the basis of general harmony, which ultimately turns into a form of statehood that would ensure peace and security for them. Thus, political organization has two basic goals, i.e., functions: the defense of the community from external enemies and the preservation of order, peace, and security within the community itself on the internal level. Thus, a state (Greek polis) is created on the basis of a contract, and politics would be defined as the art of running a state for the purpose of effectively realizing its two basic functions.

Such a (state-forming) contract prevents wars within the same (socio-political) community if the contract is fulfilled, which is in accordance with natural law. The contract imposes on each individual of the community a large number of obligations and duties in addition to rights, the fulfillment of which is necessary for the preservation of peace, order, and security. Thus, an individual, a member of a socio-political community, necessarily loses an important part of his freedom, which he transfers to the state for the sake of his own security and preservation of existence. Here, it should be noted that the law or effect of the development of civilization and the progress of the human race in the historical context is that with the development of civilization, man increasingly loses his natural freedoms and vice versa.

Thomas Hobbes believed that natural laws are, in fact, moral laws. One of the basic moral principles for the efficient and just functioning of the socio-political system, i.e., contracts, is that one should not do to others what one does not want to be done to oneself by others. Moral laws are eternal and therefore unchangeable and therefore universal for all members of a community, so all individuals strive to harmonize their behavior towards others in accordance with such moral laws. However, in the state of nature, these moral laws are powerless since they do not oblige people to behave in accordance with them, but only until real opportunities are created for all other people to be governed by them. Finally, such conditions and opportunities are created by a contract that leads to the creation and functional organization of the state.

Transition from the state of nature to the contractual state of statehood

According to Hobbes, law appears by leaving the state of nature and moving to the contractual state of statehood. Statehood is the institution that enables the creation or definition of private property between members of the community according to the principle of “mine”/“yours”. The state, as an institution, therefore, is obliged to respect the property of others. Unlike the contractual state (civilization), in the state of nature (savagery), there was no reciprocal security or guarantor of that security. By creating the state/statehood as an institution, man renounced those rights that he/she enjoyed in the state of nature. In the state of statehood, man adheres to contracts because this is the only way to ensure peace and, therefore, personal security. Thus, man shifts to fulfilling moral obligations because they contribute to the preservation of personal security.

However, as Hobbes argues, the mere contract/agreement between the members of a community is not sufficient for a state to exist and function. This requires, in addition to the contract, complete internal unity. In other words, in order to form a unified will of people, they must cease to live as independent and separate individuals, i.e., in some way they must “drown” into the general currents of the state community and thus renounce an essential part of their independence, individualism, and natural freedom. Now Hobbes moves on to the main point of his political philosophy, which has its own specific historical background, namely the time in which Hobbes lived, arguing that individuals should retain neither will nor right for themselves because all power should pass to the state as a general and superior institution. Hobbes essentially demands that individuals in a state community be subjects of the state and not citizens of it. Therefore, subjects must obey the commandments/laws of the state because only then can they distinguish good from evil. This transfer of all individual rights and powers to state bodies leads to the formation of (state) sovereignty (suma potestas/sumum imperium).

In this way, according to Hobbes, individuals are connected by a double contract/agreement:

1) A contract according to which individuals associate with each other; and

2) A contract by which, as a social collective (associated individuals), they connect themselves with a state authority to which they surrender all power with an absolute and unconditional obligation and practice of submission to it (in Hobbes’s specific historical time, this specifically meant absolutist royal authority).

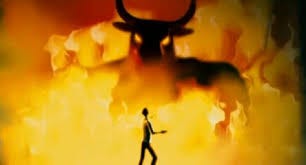

The main direct consequence of this double contract is that a single entity is formed from the plurality of individuals under the auspices of state authority. This state authority, or royal absolutist authority over subjects that has support in the church, Hobbes called Leviathan. It is a biblical monster or mortal God who, in Hobbes’s illustration, holds a bishop’s crosier in one hand and a sword in the other, i.e., attributes of spiritual and worldly power. For Hobbes, the state is neither a divine nor a supernatural creation. Man is the rational and most sublime work of nature, and the state-Leviathan is the most powerful human creation. The state itself is an artificial body compared to man, who is a natural body. The soul of the state is the supreme authority, its joints are the judicial and executive organs, the nerves are rewards and punishments, memory is the counselors, the mind is justice and laws, health is civil peace, illness is rebellion, and death is civil war.

Man created the state based on the voice of reason. According to Hobbes, the state is an artificial product of a rational move of the human race and not a natural fact, as many philosophers before him believed, such as, for instance, Aristotle. According to Hobbes, the state exercises absolute sovereignty in such a way that individuals, i.e., subjects, are alienated in the state itself, that is, they renounce their natural right and condition. In other words, by the very fact that individuals have concluded an agreement to submit to the absolute state power they have chosen, they renounce their rights, which they alienate by transferring them to the sovereign. The relationship of the individual to the state is in the form of political alienation of man in the sovereign, instead of the medieval alienation in God.

Government and its forms

Hobbes believed that his theoretical system of government could be applied in practice to all forms of state power. Specifically, for him, there were three forms of state power in their pure form: Monarchy (which he preferred); Aristocracy; and Democracy. He also allowed the establishment of parliament, but under the condition of a strong and unlimited monarch’s power. The function of such a monarch’s power is to abolish the “natural state” of the human race, i.e., the general war of all against all, with its comprehensive authority and total power, and thus ensure peace and individual security for all members of the socio-political community, i.e., the state. Freedom as the basic form of democracy leads to rebellion, anarchy, and disorder. Hobbes further believes that the monarch’s supreme power must be primarily of a sovereign character, which for him specifically meant that it should not be subordinated to any external authority (domination), subject to any law outside the law of the monarchy, whether natural or ecclesiastical.

However, in the final analysis, monarchical power, at least theoretically, was not totally unlimited, since the right to exist was for him the only right that allowed for a limitation of supreme power, i.e., obligatory submission to the sovereign. This is because the foundation of state power in any form was laid on the basis of existential survival and self-preservation. This form can in principle be monarchical, aristocratic, or democratic, but in no way mixed, i.e., the division of power between individual organs. In any case, power must be exclusively in the hands of the organ to which it is handed over. In this case, Hobbes denies the basic principle of modern democratic power, which is the division of power into legislative (parliament), executive (government), and judicial (judicial organs).

It should be noted that Thomas Hobbes was a bitter opponent of the revolution, believing that crafts and trade, and therefore, in his socio-political conditions, the rising capitalist production, would flourish under the conditions of an all-powerful state administration in which all disagreements and political struggles would be eliminated. He believed that everything that contributes to the common life of people is good and that everything that helps to maintain a strong state organization should be supported. Outside the state, passion, war, fear, and brutality reign (i.e., the state of nature), while reason, peace, beauty, and sociability reign in the state organization (i.e., civilization).

The object of the care of the state administration (absolute monarchy) must be the wealth of the citizens (i.e., subjects) created by the products of the land and water (sea), as well as work and thrift. The duty of the state is to ensure the well-being of the people. Hypothetically, the interests of the monarch should be identified with the interests of his subjects for the state to function optimally.

Synthetic remarks

Thomas Hobbes’s doctrine of the omnipotent power of the enlightened absolutist monarch is a product of a time when there was a strong need to organize a centralized and absolutist state (centripetal) organization that could, above all, successfully resist papal universalism but also serve the development of capitalism and the limitation of feudal (centrifugal) elements. From a purely economic point of view, the absolutist monarchy at that time and in the following century corresponded to the interests of the capitalist bourgeoisie and its efforts to create a large internal economic market without regional-feudal taxes and sales taxes. In this way, on the other hand, national unity would automatically be created as a guarantor of the functioning of the economy within the national framework (a single state).

Hobbes believed that the terrible natural state of war of all against all could be overcome because, in addition to passions, there is also reason in man, which teaches people to seek better and safer means for their biological, material, economic, and general life than those that lead to war of all against all. In other words, in order to ensure social peace and individual security, each individual in society must renounce the unconditional right that he/she possesses in the state of nature. Ultimately, man does this because his/her instinct for self-preservation dictates it. By this renunciation, man renounces and partakes of his natural freedom, i.e., the freedom given by natural law, because the entire social community submits to the general contract to live in a political community-state. Although all individuals accept such a contract/agreement, they do so in principle for purely egoistic reasons, but reason dictates that they do so and therefore obey certain basic virtues without which the survival of the state would be impossible (fidelity, gratitude, kindness, indulgence, etc.). Outside the state contract, i.e., the state, there are affects, war, fear, poverty, filth, loneliness, barbarism, etc. Unlike the state of nature (i.e., the state of the jungle, uncivilization and barbarism, but also total freedom in the banal sense), statehood is characterized by reason, peace, security, wealth, luxury, science, art, etc., but with the condition of drastic restriction and even abolition of natural freedoms.

Only with the formation of a state organization does the distinction between right and wrong, virtue and vice, good and evil arise. For Hobbes, the conclusion of a state-forming contract among members of a social community can be tacit, that is, informal. In any case, the conclusion of a state contract for Hobbes is of historical importance because it separates pre-history from history itself. In other words, as for many other researchers of the history of mankind, the transition from the state of the jungle (anti-civilization) to the state of statehood is also the transition to civilizational development and history in general. On the one hand, Hobbes quite correctly understood the nature of the original state of nature, but he could not explain the emergence of the state outside the framework of the social contract.

What is important to note about Hobbes’s theory of contract is that he believed that by concluding a social-state contract, the individuals who concluded it automatically transfer all their power and their rights to the state administration, i.e., the absolutist monarch. The state becomes omnipotent, despotic, and absolutist, and therefore, resembles the mythical biblical monster Leviathan. The contractual transfer of power from the individual to the state must be unconditional, and therefore, the state power itself must be unconditional. To be such, power must be in the hands of only one man, and that is the absolutist monarch who is both the sole administrator and the supreme judge. Thus, Hobbes derived from his contract theory the necessity of absolute monarchy as the only form of state administration that fully corresponds to the intentions of the social contract itself. Absolute monarchy also has other advantages over other forms of political organization that make it the best form of government. Thus, for example, in an absolute monarchy, power can be abused by only one person, in an aristocracy by several families, and in a democracy by many (here Hobbes does not distinguish between the possible depths of abuse and corruption). Furthermore, in an absolute monarchy, party struggles are more easily neutralized, and in the ideal case of total despotism, party and political struggles do not exist because there is a complete unity of society, state, and politics under the rule of one person. State secrets are also easier to keep in absolute monarchies.

An absolute monarch must also have absolute power, i.e., absolute right in all political-legal and moral relations in the state (“The state, that is me”!). The monarch (in Hobbes’ case, the king) is the one who has both the first and the last word in all ecclesiastical, religious, and moral matters. Thus, the monarch determines how God is to be worshipped; otherwise, what would be worshipable to one person would be blasphemous to another, and vice versa. Thus, society within the same state would be divided into hostile parties and would wage a struggle between these parties on religious issues (like, for instance, the Holy Roman Empire during the religious wars in the 16th and 17th centuries). In other words, Thomas Hobbes was a great opponent of any religious tolerance within the same political organization. For him, it is an unacceptable revolutionary act for someone to oppose the valid and only permitted religion based on their private religious convictions, because in this way, the very survival of the state as well as its normal functioning is called into question. Therefore, what is generally good and what is bad for society and the state is decided only by the monarch. Moral conscience consists in obedience to the monarch.

Thomas Hobbes, nevertheless, later allowed for limitations on royal absolutism, and believed that every power was just if it served the people, and that this could ultimately be even a republic (Commonwealth), but headed by an in fact absolutist figure (e.g., Oliver Cromwell). Hobbes’s theory of statehood turned from the medieval theological to the anthropological interpretation of the origin and foundations of the state. Hobbes’s teaching on the emergence of state organization based on contracts and the understanding that life would be better and safer in the state was contrary to medieval theological interpretations and understandings of the state, which identified the goals of the feudal class of large landowners with divine goals. Many philosophers have seen Hobbes’ theory of the state as the doctrine of the modern totalitarian state. However, Hobbes’s political philosophy is essentially individualistic and rationalistic.

Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic is an ex-university professor and a Research Fellow at the Center for Geostrategic Studies in Belgrade, Serbia.