Sidney Paget, Arthur Conan Doyle, “Silver Blaze,” Strand Magazine, Dec. 1892, p.646.

The crime

The crime last week — bombing a foreign country and kidnapping its president* – was nothing new. The U.S. did it in Panama in 1989 and Libya 12 years later, though in the latter case, the president (Muammar Gaddafi) was captured, tortured and killed by allied, local forces. The list of countries attacked, invaded or leaders deposed by the U.S. in the last 75 years is familiar to many Counterpunch readers. I present it here as dark poetry:

Guatemala, Grenada, Pakistan,

Somalia, Cuba, and Sudan.

Panama, Libya, Afghanistan,

Cambodia, Korea, and Vietnam.

El Salvador, Iraq, Iran,

Yemen, Nicaragua, and Lebanon,

Laos, Venezuela, and Republic Dominican.

Excluded are countries where the U.S. plotted coups or assassinations – mere bagatelles compared to the rest: The war against Vietnam killed some 2 million, not including 55,000 Americans. Since 9/11, according to the Brown University Costs of War project, U.S. violence has killed – directly or indirectly – about 4.5 million people in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen and Pakistan.

Except when it showcased enemy body counts early in the Vietnam War to demonstrate battlefield progress, U.S. government officials have generally minimized or denied death tolls. Where obfuscation was impossible, they absolved themselves by claiming that war was thrust upon the U.S., and that the invaded nation: a) was the aggressor; b) colluded with communists, Islamic terrorists or drug traffickers; c) threatened its neighbors and global peace; d) possessed weapons of mass destruction; e) endangered global trade and American prosperity; or f) used civilians as human shields. Never have high ranking U.S. officials admitted moral or legal culpability, even decades after the violence. The conduct of the Vietnam war, according to President Barack Obama, winner of the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize, was marked by “mistakes” not crimes. Indeed, he said, the real “disgrace” was the American failure to adequately honor returning vets. No matter how the Venezuela adventure turns out, don’t expect any administration official to backtrack or apologize.

A surprising confession

The attack on Venezuela was premediated and unsurprising except in one, significant respect: U.S. officials, most notably the garrulous president, did not mask their motives, minimize the violence, or prevaricate – well, not much. The U.S. invaded Venezuela and kidnapped its president, Trump said, half-truthfully, to gain control of its oil industry and repay American companies whose property was “stolen” by the former government. In fact, the nationalization law of 1976 was nothing like a theft. It was uncontroversial at the time, except to those who saw it as a surrender to U.S. and corporate interests. The Venezuelan government paid a billion dollars in compensation to the two major oil producers, Creole Petroleum (USA) and Shell Oil (multinational), and otherwise maintained existing service agreements. In 2007, President Hugo Chavez decreed that foreign oil companies receive a smaller share of Venezuela’s oil revenues. Some petroleum giants – notably ExxonMobil and Conoco/Phillip – were unsatisfied and sued for compensation in international court. Venezuela agreed a smaller settlement than the court decreed, and negotiations continue.

But for anyone who remembers the slogan “no blood for oil” chanted at protests against the first Gulf War (1990-91) and U.S. invasion of Iraq (2003), Trump’s admission was stunning. Here are his exact words, published on his Truth Social website:

“I am pleased to announce that the Interim Authorities in Venezuela will be turning over between 30 and 50 MILLION Barrels of High Quality, Sanctioned Oil, to the United States of America.

“This Oil will be sold at its Market Price, and that money will be controlled by me, as President of the United States of America, to ensure it is used to benefit the people of Venezuela and the United States!”

Reporters, columnists and some U.S. politicians pounced on the divulgence to underline that Trump’s intervention in Venezuela had nothing to do with supposed drug shipments, as he previously claimed. (In fact, the country ships no fentanyl and little cocaine to the U.S.) Instead, it was born of greed and corporate payback. U.S. fossil fuel interests contributed nearly $500 million to Trump’s 2024 election campaign, and the president pledged to return that investment with interest.

Trump’s admission was in effect retrospective as well as prospective. If the current invasion of a major, oil producing nation was a war for oil, so must earlier Mideast, petrostate interventions. Whatever rhetorical justifications deployed by Bush I in 1991 (the sanctity of Kuwait’s borders) and Bush II in 2003 (weapons of mass destruction) they are now admitted to be prevarications. In fact, the entire edifice of U.S. foreign policy, Trump’s confession suggests, has been a tissue of lies: “containment,” “missile gap”, “Islamic terrorism,” “Soviet expansionism,” “pivot to Asia,” “rules-based order” and so on. The only thing exceptional about U.S. foreign policy is its fraudulence and the size of the military budget that underlies it, exceeding every other country in the world combined.

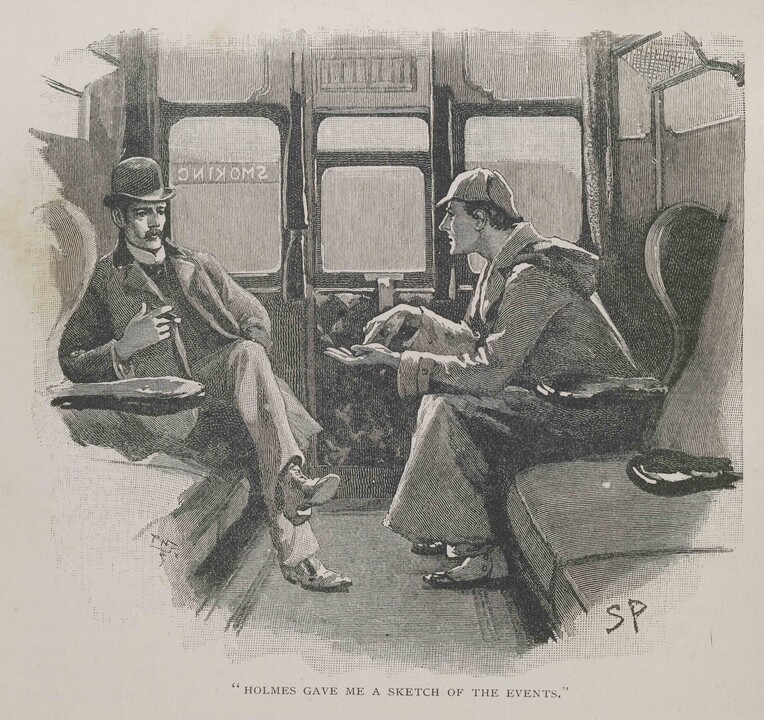

“The curious incident of the dog in the night-time”

In Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story, “The Story of Silver Blaze,” (1892), the mystery of a stolen horse and murdered trainer is solved by “the curious incident of the dog in the night-time” –Sherlock Holmes’ discovery that the dog guarding the horse barn didn’t bark, meaning the criminal was someone known to the canine. The sleuth of Baker Street might make a similar observation today. The most remarkable thing about Trump’s Venezuela confession is that the dog didn’t bark — there has been no mass, public outcry, no demands for investigations, and no cries for impeachment. Opinion polls indicate that slightly more Americans support the president’s actions in Venezuela (43%) than his overall performance (41%). Did Americans already know the truth Trump confessed?

Generations of presidents have been at pains to mask imperial plans out of concern that voters would reject them and punish their authors. But Trump openly acknowledged that the goal of his foreign policy is to bully the weak and increase corporate profits. His mini-me, Assistant Chief-of-Staff Stephen Miller, justified the seizure of Maduro and Venezuelan oil in Nietzschean terms: “We live in a world… the real world, that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power.” The Defense Secretary, Secretary of State, and U.N. ambassador have been equally blunt. How do we explain the sudden emergence of what T.J. Clark recently called “a politics where nothing is hidden?” And what accounts for Americans’ collective shrug?

A possible explanation for the first is that spectacular violence has become the end, not the means of government policy. The surge of U.S. sponsored mayhem – in Gaza, on the high seas, in Iran, Venezuela and at home in ICE targeted communities – may prove to be the terminal expostulation of American, democratic capitalism. Morbid symptoms have been apparent for some time: political parties wholly subservient to corporate interests; voters chosen by their representatives not vice versa (gerrymandering); representatives powerless to tax billionaires and regulate corporations out of fear they will relocate or replace workers with AI. Lacking real power, Trump and his coterie deploy the spectacle of violence and war, “the realm,” Clark writes, “where the state still calls the shots.” Clausewitz famously said: “War is the continuation of policy by other means”. Increasingly, under Trump, policy is the continuation of war by other means. Legislation concerning drugs and immigration takes a back seat to the performance of blowing up supposed drug boats, bombing Caracas, and the horror of masked and armed ICE agents corralling or shooting immigrants (and non-immigrants) in Democratic-led cities.

Two explanations for public indifference to Trump’s confession that he targeted Venezuela to pay back “our oil companies,” present themselves. First, as suggested earlier, that the thrall cast by ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Valero Energy, Marathon Petroleum etc., on U.S. politics is old news. You don’t need to have read Adam Smith to recognize monopoly pricing in the oil industry. Dueling corner stations with the exact same price for gas (to the tenth of a penny) offer drivers a daily lesson in price fixing. If Americans have continued to vote for politicians beholden to oil companies, it’s because they understand, correctly, that the deference afforded the latter by the former differs little whether Republicans or Democrats are in charge.

The second reason for the collective shrug is that whatever its rationale, people are waiting to see if they gain or lose from the attack on Venezuela. If prices fall for gas, food, rent, healthcare, education and entertainment, they will support it; if they don’t, they won’t. When domestic circumstances are dire, foreign policy is just background noise.

Prospects for resistance

Nevertheless, it should not just be taken as a given that the mass of Americans will forevermore remain indifferent to the spectacle of violence abroad and at home. It took years, and mounting American dead, for the tide of public opinion to turn against the Vietnam war, but when it did, the U.S. abandoned the field of battle. Reagan’s saber rattling and Star Wars initiative persuaded millions of Americans that their survival depended upon sustained, anti-nuclear protest. The result was a series of nuclear arms reduction treaties with the Soviet Union, partly undone by Republican presidents, including the current one.

Already, signs of mobilization against Trumpian fascism (debate over that term is now over) are apparent. Government support for Israel’s genocide against Palestinians in Gaza prompted mass, student protests last year. The garrisoning of ICE agents – veritable storm troopers – in Democratic led cities, has prompted thousands to join citizen patrols to warn immigrants of impending raids, and harass government forces, mostly with taunts and video recordings. The latter it seems, are especially galling to agents recruited with the promise of becoming action heroes like ones they see on TV.

Though the fascist right has until recently monopolized social media, that has started to change. For every Tucker Carlson, Nick Fuentes, Laura Loomer, and Steve Bannon on X, YouTube, Instagram, Tik Toc and Truth Social, there’s now a Hasan Piker, David Parkman, Ana Kasparian (“The Young Turks”), and Mehdi Hasan on the same sites or with their own channels and podcasts. While the right still commands more eyeballs than the left, the gap is narrowing.

What radicals and progressives in the U.S. need as much or more than social media stars, however, is actual, on the ground activists and organizers. While the best influencers may affect day to day public opinion, and perhaps even cyclical voting habits, they don’t appear to have the kind of long-term impact that leads to structural change. For that, what’s needed is people on the ground, talking to citizens about their anxieties, sense of powerlessness, hopes and desires. Talented organizers – the U.S. has many and I’ve known a few – can establish relationships with community members far more profound and lasting than between influencers and their unseen audience. They can help people understand the path their life has followed, the obstacles they have overcome, and how to achieve more in the future. Those conversations inevitably lead to strategies to join forces with others to intervene into the domain of power.

Only when groups or parties on the left begin to educate and organize — in living rooms, coffee shops, church basements, community centers, school auditoria and in the streets — will they begin to shift politics away from spectacular displays of domination toward the satisfaction of genuine human needs. That’s when aggression like we have seen in Venezuela and on the streets of American cities will raise alarms that cannot be ignored and prompt demands that cannot be refused.

*Whether or not the January 2025 election that returned Maduro to the presidency was free and fair is no more America’s business than the election of Donald Trump in 2016 – when he received 3 million less votes than Hilary Clinton — is Venezuela’s.