Long before September 2, Pete Hegseth had systematically dismantled the guardrails that prevented him and his subordinates from committing war crimes.

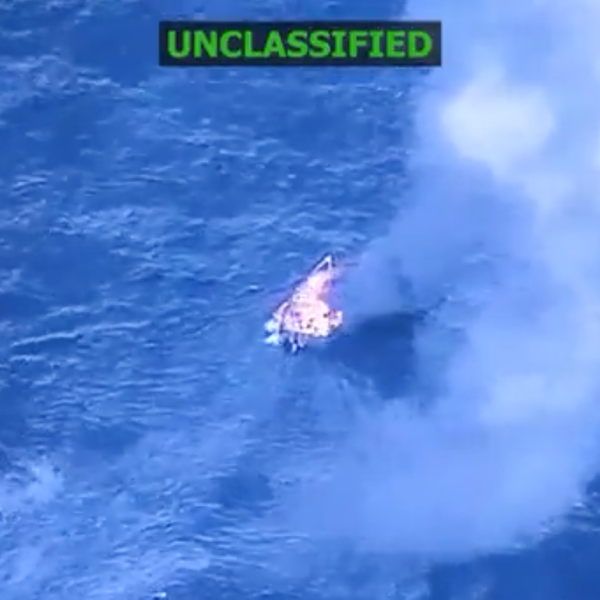

This image was posted on social media by President Donald Trump and shows a boat that was allegedly transporting cocaine off the coast of Venezuela when it was destroyed by US forces on September 2, 2025.

(Photo by President Donald Trump/Truth Social)

Dec 04, 2025

On Friday, November 28, the Washington Post reported that when the US military began attacking small boats in the Caribbean, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth had issued a verbal order that it should “kill everybody.”

When the first attack occurred on September 2, the initial missile strike destroyed the boat but left two survivors clinging to the wreckage. To comply with Hegseth’s order, Admiral Frank M. “Mitch” Bradley authorized a second strike that killed them.

If true, it’s a war crime.

Hegseth called the Post‘s reporting “fabricated, inflammatory, and derogatory,” claiming that the drug-smuggling operations were “lawful under both US and international law.”

Then the doubletalk began.

Story #1: “That Didn’t Happen”

On November 30, President Donald Trump weighed in.

“He did not say that,” Trump said of Hegseth’s reported order, “and I believe him 100%.”

Perhaps sensing a war crime when he sees one, Trump added, “I wouldn’t have wanted that. Not a second strike. The first strike was very lethal. It was fine, and if there were two people around, but Pete said that didn’t happen.”

Hegseth should know. The day after the attack, he told Fox & Friends that he’d watched the operation live.

Story #2: “There Was No Specific Order to Kill Survivors”

On Monday, December 1, White House spokesperson, Karoline Leavitt, admitted that the second strike occurred, but denied that Hegseth said “kill everybody.” She identified Admiral Bradley as the trigger man for the second strike.

That evening, the New York Times reported that five US officials speaking anonymously said that Hegseth “ahead of the September 2 attack, ordered a strike that would kill people on the boat and destroy the vessel and its purported cargo of drugs.” But, the Times continued, “Hegseth’s directive did not specifically address what should happen if a first missile turned out not to fully accomplish all of those things. And, the officials said, his order was not a response to surveillance footage showing that at least two people on the boat survived the first blast.”

Story #3: Hegseth Didn’t See the Second Strike After All

During Trump’s appearance with the cabinet on December 2, Hegseth asserted that he actually hadn’t watched the second strike and wasn’t even in the room when Bradley ordered it. After throwing the distinguished admiral under the bus, Hegseth said that Bradley had adhered to the laws of war.

Story #4: Trump Has a License to Kill

In the end, Trump and Hegseth reverted to their original justification for the entire boat-bombing operation: The drug smugglers are “narco-terrorists” engaged in armed combat with the United States and its allies. According to this unsupported claim, the cartels aren’t smuggling drugs just to make money. They’re in business to finance terrorism aimed at US allies.

Most legal scholars don’t buy it. Even drug runners are civilians and therefore not appropriate military targets. But Trump claims the right to order the summary executions without providing evidence of their crimes or the pretense of due process. In his view, civilians are “collateral damage” as the nation exercises its right of self-defense. But even under Trump’s strained reasoning, strike survivors would be prisoners of war.

The Real Story

The controversy over who ordered what misses a fundamental point: Hegseth’s incompetence is the real story. The second attack resulted from either his direct order (“kill everybody”) or ambiguity in whatever order he gave.

Hegseth’s prior actions created the environment for disaster. Long before September 2, he had systematically dismantled the guardrails that prevented him and his subordinates from committing war crimes.

Beginning in February 2025: Over the next 10 months, Hegseth purged or sidelined two dozen of the nation’s most experienced generals and admirals.

February 2025: Hegseth fired the top lawyers for the Army, Navy, and Air Force. These senior judge advocates general (“JAGs”) provide independent legal advice to top military officers so that they do not run afoul of US law or the laws of armed conflict. At the time, Hegseth said that he was removing “roadblocks to orders that are given by a commander in chief.”

August 2025: According to NBC News, the senior judge advocate general for the US Southern Command overseeing the strikes on alleged drug-smuggling boats disagreed with Trump’s position that the operations were lawful. A Pentagon spokesperson denied the report.

September 2: The US conducted its first attack.

September 16: Increasingly, legal experts questioned the justification for Trump’s boat attacks. For example, John Yoo, former deputy attorney general under President George W. Bush and author of the legal rationale for enhanced interrogation techniques against suspected al Qaeda terrorists, said, “[T]he administration needs to make a stronger case than it’s been making so far about why the law should consider cartels to be enemies of war.”

October 16: US military forces attacked another small boat in the Caribbean, but this time two survivors were taken into custody and repatriated to their respective countries, Colombia and Ecuador.

The same day and only a year into his three-year appointment as head of the US Southern Command overseeing all operations in Central and South America, Admiral Alvin Holsey stepped down from his position. Holsey reportedly expressed concerns about the escalating boat attacks.

Trump Undermined His Own Rationale

While seeking to justify lethal attacks on small boats in the Caribbean as a war on narco-terrorists, on December 1, Trump pardoned one of the most prominent narcotics smugglers in the world—former Honduras President Juan Orlando Hernández. He had been serving a 45-year sentence for drug trafficking and weapons charges. According to court documents, from at least in or about 2004, up to and including in or about 2022, Hernández was at the center of one of the largest and most violent drug-trafficking conspiracies in the world.

Trump claimed that Hernández was the victim of political persecution. If so, Trump’s first administration was among the persecutors. In 2013, the Justice Department began an investigation into Hernández that continued during Trump’s entire first term. One of the prosecutors was Emil Bove III, who went on to become Trump’s Justice Department hatchet man in the second Trump administration before his lifetime appointment as a federal appellate judge.

Hernández was engaged in the very activities that Trump now uses to justify killing suspected drug smugglers. But Hernández got due process, a trial, and a sentence that would have put him in prison for the rest of his life—until Trump pardoned him.

Trump in a Nutshell

Contrast Hernández freedom with the fate of Any Lucía López Belloza, a 19-year-old Babson College student. Twelve years ago, her family fled the violence, crime, and economic stagnation of Honduras under Hernández’s rule. On November 20, 2025, while preparing to board a plane in Boston to go home for Thanksgiving, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arrested her.

Belloza’s lawyer said that on November 21, a federal judge ordered that she could not be deported while her case was pending. But after spending the night in a Texas detention center, on November 22 agents shackled her wrist, waist, and ankles and put her on a flight to Honduras.

She doesn’t know if or when she will return to the United States.

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

Steven Harper

Steven J. Harper is an attorney, adjunct professor at Northwestern University Law School, and author of several books, including Crossing Hoffa -- A Teamster's Story and The Lawyer Bubble -- A Profession in Crisis. He has been a regular columnist for Moyers on Democracy, Dan Rather's News and Guts, and The American Lawyer. Follow him at https://thelawyerbubble.com.

Full Bio >

Framing “Operation Southern Spear” as a battle against “narco-terrorists” is a desperate attempt to commit new violence using old excuses, one which ignores the security state’s history of creating its own enemies.

US Secretary of War Pete Hegseth (C) speaks during a Cabinet meeting alongside (L-R) US President Donald Trump, US Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick, and US Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy in the Cabinet Room of the White House on December 2, 2025 in Washington, DC.

(Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Brett Heinz

Dec 04, 2025

Between the War on Drugs and the War on Terror, the US government has a long history of waging bloody and unsuccessful wars against broad concepts that can not be meaningfully defeated. What makes the government’s latest “armed conflict” unique is not just its combination of these two failures, but also that its target—“narco-terrorism”—is largely a myth.

Under the title “Operation Southern Spear,” the Trump administration has launched a campaign intended to target the drug cartels that it designated as terrorist organizations earlier this year. So far, this has involved at least 21 airstrikes, killing upwards of 83 people on small boats in the Caribbean and the Pacific; a military buildup involving 15,000 troops; and covert operations by the CIA in Venezuela. Though President Donald Trump lacks the legal authority for these activities, the Senate’s latest attempt to restrain military action failed in a narrow vote of 49-51.

Trump Killing Spree Continues as Murder Count Rises to At Least 70 People

Key to the White House’s case is the idea of “narco-terrorism,” a label they have applied to both the airstrike victims and Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro. The US claims that Maduro is closely connected to the Tren de Aragua cartel (despite a National Intelligence Council analysis suggesting otherwise) and that he is the leader of the supposed “Cartel of the Suns” (which, despite its terrorist designation, does not exist as an organization). The specter of “narco-terrorism” has also been invoked to bash the progressive governments of Colombia and Honduras.

To say that “narco-terrorism” is a myth is not to deny the obvious violence associated with the black market drug trade, but to acknowledge that the term does more to confuse than to clarify. The idea does not accurately explain the complex dynamics of the global drug trade; instead, it radically oversimplifies the problem. By portraying military intervention as a response to drug trafficking, the “narco-terrorism” myth allows politicians to ignore all of the ways in which military intervention is a cause of drug trafficking.

Strange Origins

“Narco-terrorism” has its origins in the early 1980s, when US Ambassador to Colombia Lewis Tambs began referring to leftist rebel groups like FARC and ELN as “narco-guerillas.” Some of his specific claims were fabricated: After Colombian police completed what was then the largest drug bust in history, Tambs falsely claimed that communist rebels were involved in the operation, prompting another State Department official to admit that “Tambs got ahead of the evidence.” Regardless, the idea quickly gained acceptance as a justification for military intervention in Latin America, suggesting that the only way to reduce drug abuse at home was to wage war against foreign suppliers. By 1985, the Reagan administration was alleging an “emerging alliance between drug smugglers and arms dealers in support of terrorists and guerrillas.”

Ironically, Tambs himself later played a role in the Iran-Contra scandal, helping to traffic drugs and guns for the violent anti-communist Contras in Nicaragua. The full scope of the CIA’s involvement in bringing the Contra’s drugs into the US remains unclear, but at the very least it is obvious that officials like Tambs helped support the group. Thus, the idea of “narco-terrorism” was created by someone who participated in it.

The “narco-terrorism” label has always been controversial. Drug traffickers are motivated solely by profit, while “terrorists” and “guerillas” are motivated by goals like ideology and territory. Though some armed groups in Latin America engaged directly in the drug trade, many others either had no involvement or were involved only by “taxing” traffickers for revenue. “Narco-terrorism” misrepresents this extortion racket between two opposed groups as an alliance of like-minded organizations. By “combining two threats that have traditionally been treated separately,” critics argue that the term can “complicate rather than facilitate discussions on the two concepts…”

Many of the largest foreign interventions in US history created new pathways for drugs to reach the country while also generating new demand among traumatized veterans.

Far from being allies, rebels and drug traffickers often fought one another. Most rebels were communist outsiders, while many traffickers hoped to build ties with Colombia’s elite. The rebels sometimes imposed wage and price controls in coca-growing communities in hopes of building popular support, rules which ate into the traffickers’ profits. These tensions eventually escalated into violent conflict, and it was later revealed that dozens of officers from the US-backed Colombian military had collaborated with the traffickers in a campaign to crush the rebels. The rebels and traffickers were “staunchly opposed social forces” in the words of journalist Collet Merrill, meaning that “narco-guerilla” was “less an analytical model than a political slogan.”

The Trump administration’s definition of “narco-terrorism” seems even less useful than its original meaning. Speaking to the United Nations, a US delegate commented on the recent terrorist designations of cartels to say: “When you flood American streets with drugs, you are terrorizing America...” Similarly, the White House claims that drug imports “constitute an armed attack” all by themselves. In other words, traffickers no longer need to have any “terrorist” connections to be considered “narco-terrorists,” because all drug trafficking is now considered “terrorism.”

The language used in our debates about drug trafficking is poisoned by this type of imprecision. Even the concept of a “cartel” is suspect, as it often portrays loose networks of organized criminals cooperating with state authorities as well-coordinated paramilitaries that lack government connections. This sort of terminology survives because of its usefulness to government officials in search of ready-made explanations, officials who did not want to draw attention to their own role in the global drug trade.

Stop Hitting Yourself

Many of the largest foreign interventions in US history created new pathways for drugs to reach the country while also generating new demand among traumatized veterans, leading some scholars to conclude that “every major foreign war of the past century produced a domestic drug crisis.” At times, the US government has even purposefully supported drug traffickers to advance its short-term objectives.

During the Vietnam War, the CIA allegedly facilitated drug trafficking in Southeast Asia to help fund anti-communist organizations, helping to turn the region into the source of the majority of the world’s heroin by the early 1970s. Much of this heroin made its way to US soldiers stationed overseas and, through the trafficking efforts of troops like Army Master Sergeant Ike Atkinson, to the United States itself. The subsequent rise in drug addiction helped inspire the original “War on Drugs,” a war which the US fought on both sides of.

The pressures of the Drug War helped bring Mexican “cartels” into existence. One of the first such organizations—the “Guadalajara Cartel”—emerged as an organized effort to survive the joint US-Mexican attempts at destroying the then-disorganized drug trade. Later efforts to support foreign security forces backfired when some of the Mexican soldiers who received special forces training in the US defected to form their own cartel: “Los Zetas,” which carried out a wave of extreme violence in Mexico in the 2000s-2010s.

With our focus exclusively on military efforts to disrupt the supply of drugs, little time is spent on the real solution: reducing demand.

Similarly to Vietnam, the War in Afghanistan created new channels for heroin trafficking. After the Taliban lost control of the country, a US government report noted that Afghanistan saw “increased poppy cultivation and drug production as farmers and traffickers took advantage of the power vacuum…” The growing opium trade corrupted the highest levels of US-backed leadership in Afghanistan. As a result, US-occupied Afghanistan was “producing nine times more heroin than the rest of the world combined,” according to journalist Seth Harp.

Sensing a profitable opportunity to connect this supply of heroin with the demand at home, a group of current and former US troops began smuggling the opium into the world’s largest military base, Fort Bragg. These smugglers then moved the drugs around the country by plugging into the distribution network of the Los Zetas cartel (whose founders had coincidentally received training at Fort Bragg decades earlier). US military interventions thus produced all of the necessary ingredients to inflame the opioid crisis: a flood of new heroin production abroad, flights to smuggle it into the US, and a cartel with the skills to distribute it.

These are just a few of the moments throughout history when the US government facilitated drug trafficking all over the world. More recently, the US provided extensive support to Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández despite widespread allegations that he was connected to cocaine trafficking. Only after he left office did the US government bother to indict him for “protect[ing] some of the largest drug traffickers in the world,” helping to bring more than 400 tons of cocaine into the country. In an absurd act of hypocrisy, President Trump recently pardoned Hernández on the grounds that the convicted drug trafficker was “treated very harshly and unfairly.”

Believe it or not, this was not even the first time that something like this had happened. In the 1980s, the Reagan administration tolerated the obvious drug trafficking of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega because of his cooperation with their geopolitical priorities. As with Hernández, the government even provided cover for Noriega by claiming that he helped fight against drug trafficking. But when US officials finally lost patience with him near the end of the decade, a Panamanian official predicted that “suppressing drug trafficking might be the Reagan administration’s excuse for an invasion.”

Though George H.W. Bush claimed that the 1989 invasion of Panama was intended in part “to combat drug trafficking,” others were skeptical. The Academy Award-winning documentary The Panama Deception argued that the true purpose of the invasion was to reinforce US dominance over the Panama Canal (a topic which is now an obsession of President Trump’s). Though this regime change operation against a former ally serves as a classic example of how military interventionism creates its own villains, it is now often remembered as a success, even earning praise from Republicans arguing in favor of Trump’s airstrikes. Panamanian diplomat Carlos Ruiz-Hernández recently criticized this comparison as a “fundamentally flawed” analogy which “persists because it’s emotionally satisfying for US hawks.”

Get Real

By misunderstanding and overemphasizing a select few of the groups involved in the drug trade, the “narco-terrorism” myth redirects our attention away from more significant causes of drug trafficking. First, the focus on supply distracts us from the far more important question of demand—so long as drug addiction remains a major problem in this country, the drugs will always find a way in. Additionally, the exclusive focus on non-state actors distracts us from the role that our own government plays in facilitating the global drug trade.

Framing “Operation Southern Spear” as a battle against “narco-terrorists” is a desperate attempt to commit new violence using old excuses, one which ignores the security state’s history of creating its own enemies. In truth, this is a domestic problem as much as a foreign one. Of those convicted of drug trafficking in the US, 80% are citizens. MS-13, now designated as a foreign terrorist organization, was founded in Los Angeles and spread abroad by the US government’s deportation practices. More than two-thirds of the Mexican cartels’ guns come from the US, and US military weaponry regularly shows up in the hands of cartel members.

With our focus exclusively on military efforts to disrupt the supply of drugs, little time is spent on the real solution: reducing demand. In fact, the Trump administration has undermined real public health solutions by repeatedly firing employees at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, discouraging lifesaving harm reduction efforts, and proposing massive cuts to drug abuse services. No amount of immoral and illegal airstrikes will ever save even a fraction of the lives lost by these decisions.

Perhaps the greatest flaw of “narco-terrorism” is that it encourages us to believe that complex human problems have simple military solutions. Sociologist C. Wright Mills once astutely criticized US elites for accepting a “military definition of reality,” a distorted perspective which prevents them from imagining policy solutions that do not involve military intervention. So long as the government insists upon seeing non-military problems through a military lens, they will never be solved.

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

Brett Heinz

Brett Heinz is a political researcher and writer currently based in Washington, D.C., with a focus on economic justice, political inequality, and U.S. foreign policy. He currently works as a National Security/Foreign Influence intern at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, and previously analyzed U.S. relations with Latin America at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Brett was born and raised in North Carolina, holds a Bachelor's degree from UNC Chapel Hill, and is now working on his MPP at American University.

Full Bio >

“US military attacks on alleged drug traffickers at sea,” said two human rights experts, “are grave violations of the right to life and the international law of the sea.”

A small boat is seen near the USS Sampson, a US Navy missile destroyer, off the coast of Panama City, Panama, on September 2, 2025.

(Photo by Daniel Gonzalez/Anadolu via Getty Images)

Julia Conley

Dec 04, 2025

COMMON DREAMS

Two United Nations rights experts warned that in numerous ways in recent weeks, the Trump administration’s escalation toward Venezuela has violated international law—most recently when President Donald Trump said he had ordered the South American country’s airspace closed following a military buildup in the Caribbean Sea.

But the two officials, independent expert on democratic and international order George Katrougalos and Ben Saul, the UN special rapporteur on protecting human rights while countering terrorism, reserved their strongest condemnation and warning to the US for the administration’s repeated bombings of boats in the Caribbean and the Pacific, which have targeted at least 22 boats and killed 83 people since September as the White House has claimed without evidence it is combating drug traffickers.

The strikes, said Katrougalos and Saul, “are grave violations of the right to life and the international law of the sea. Those involved in ordering and carrying out these extrajudicial killings must be investigated and prosecuted for homicide.”

Human rights advocates have warned for months that the strikes are extrajudicial killings. Trump has claimed the US is in an “armed conflict” with drug cartels in Venezuela—even though the country is not significantly involved in drug trafficking—but Congress has not authorized any military action in the Caribbean.

Typically, the US has approached drug trafficking in the region as a criminal issue, with the Coast Guard and other agencies intercepting boats suspected of carrying illegal substances, arresting those on board, and ensuring they receive due process in accordance with the Constitution.

The Trump administration instead has bombed the boats, with the first operation on September 2 recently the subject of particular concern due to reports that Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth issued an order for military officers to “kill everybody” on board a vessel, leading a commander to direct a second “double-tap” strike to kill two survivors of the initial blast.

Hegseth and Trump have sought to shift responsibility for the second strike onto Adm. Frank “Mitch” Bradley, the commander who oversaw the attack under Hegseth’s orders. Bradley was scheduled to brief lawmakers Thursday on the incident.

The White House has maintained Bradley had the authority to kill the survivors of the strike and to carry out all the other bombings of boats, even as reporting on the identities of the victims has shown the US has killed civilians including an out-of-work bus driver and a fisherman, and the family of one Colombian man killed in a strike filed a formal complaint accusing Hegseth himself of murder.

The UN experts suggested that everyone involved in ordering the nearly two dozen boat strikes, from Trump and Hegseth to any of the service members who have helped carry out the operations, should be investigated for alleged murder.

After Hegseth defended the September 2 strike earlier this week, Saul emphasized in a social media post that contrary to the defense secretary’s rhetoric about how the boat attacks are “protecting” Americans, he is carrying out “state murder of civilians in peacetime, like executing alleged drug traffickers on the streets of New York or DC.”

As Common Dreams reported last month, a top military lawyer advised the White House against beginning the boat bombings weeks before the September 2 attack, saying they could expose service members involved in the strikes to legal challenges.

Katrougalos and Saul urged the administration to “refrain from actions that could further aggravate the situation and ensure that any measures taken fully comply with the UN Charter, the Chicago Convention, and relevant rules of customary international law.”

They also emphasized that Trump had no authority to declare that Venezuela’s airspace was closed last week—an action that many experts feared could portend imminent US strikes in the South American country.

“International law is clear: States have complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above their territory. Any measures that seek to regulate, restrict, or ‘close’ another state’s airspace are in blatant violation of the Chicago Convention,” said the experts. “Unilateral measures that interfere with a state’s territorial domain, including its airspace, risk fully undermining the stability of the region and are seriously undermining Venezuela’s economy.”

Saul and Katrougalos further called on the White House not to repeat “the long history of external interventions in Latin America.”

“Respect for sovereignty, nonintervention, and the peaceful settlement of disputes,” they said, “are essential to preserving international stability and preventing further deterioration of the situation.”

“Two individuals in clear distress, without any means of locomotion, with a destroyed vessel, were killed by the United States.”

US Rep. Jim Himes (D-Conn.) speaks to members of the press after a briefing at the US Capitol on February 14, 2024 in Washington, DC.

(Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Brad Reed

Dec 04, 2025

COMMON DREAMS

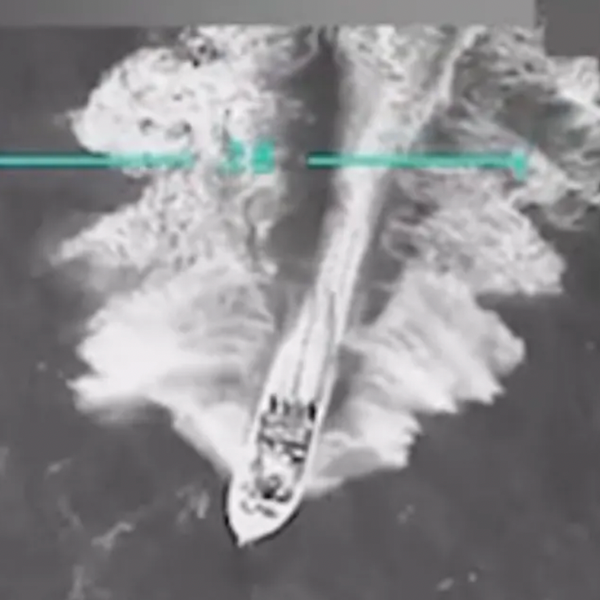

US Rep. Jim Himes, the ranking member of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, expressed horror on Thursday after watching a video of the September 2 double-tap strike on a suspected drug trafficking vessel off the coast of Trinidad and Tobago.

Speaking to reporters after a briefing on the strike delivered by Adm. Frank Bradley, Himes (D-Conn.) called the video he saw of the attack “one of the most troubling things I’ve seen in my time in public service.”

Demands to Release Full Video of Deadly US Boat Strike Grow After Congressional Briefing

Himes proceeded to describe the video, which showed the US military firing missiles at two men who had survived an initial attack on their vessel and who were floating in the water while clinging to debris.

“You have two individuals in clear distress, without any means of locomotion, with a destroyed vessel, [who] were killed by the United States,” he said.

Himes then started to walk away before a reporter asked him to describe more of what he saw in the video. The Connecticut Democrat then said the video showed a clear “impermissible action,” according to the laws of armed conflict.

“Any American who sees the video that I saw will see its military attacking shipwrecked sailors,” he said. “Now, there’s a whole set of contextual items that the admiral explained. Yes, they were carrying drugs. They were not in position to continue their mission in any way... People will someday see this video and they will see that that video shows, if you don’t have the broader context, an attack on shipwrecked sailors.”

Himes finished his talk with reporters by saying that Bradley told lawmakers there had not been a “kill them all” or “no quarter” order given to him by higher-ups. Asked by a reporter if he thought the full video should be released to the public, Himes said, “I do.”

Himes’ reaction to the video stood in stark contrast to the reaction of Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.), the chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, who praised the military for its actions.

According to HuffPost reporter Jen Bendery, Cotton described the strikes on the two survivors as “righteous strikes” that were “entirely lawful.”

Cotton also claimed that the video showed “two survivors trying to flip a boat, loaded with drugs, bound for the United States, back over, so they could stay in the fight.”

Reports from the US government and the United Nations have not identified Venezuela as a significant source of drugs that enter the United States, and the country plays virtually no role in the trafficking of fentanyl, the primary cause of drug overdoses in the US.

Additionally, many legal scholars have said that a strike on the two men who survived the initial attack on the boat is very likely either an act of murder or a war crime, regardless of whether they were intending to traffic illegal drugs in the US.

Venezuela’s opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro, and the United States President Donald Trump IMAGE/

Venezuela’s opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro, and the United States President Donald Trump IMAGE/ Venezuela’s opposition leader Maria Corina Machado and Donald Trump Jr. IMAGE/

Venezuela’s opposition leader Maria Corina Machado and Donald Trump Jr. IMAGE/ United Nations’ Francesca Albanese defiant amid Israeli pressure and Gaza catastrophe IMAGE/

United Nations’ Francesca Albanese defiant amid Israeli pressure and Gaza catastrophe IMAGE/