Taking over Greenland, a long-standing US obsession

ANALYSIS

Days after US forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro in Caracas, US President Donald Trump suggested that other regions of the world could be on Washington’s radar, including Greenland. Ever since his first term, the billionaire has repeatedly expressed interest in the mineral-rich Danish autonomous territory in the Arctic – a focus that predates Trump’s presidency.

Issued on: 07/01/2026

By:

Stéphanie TROUILLARD/

Romain HOUEIX/

Sébastian SEIBT

US President Donald Trump is considering "several options" to acquire Greenland, including "using the military", his spokeswoman Karoline Leavitt said on Tuesday, stoking further concern in Europe over the future of the Arctic island.

In a joint statement, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain and the UK voiced support for Denmark against Trump’s claims over the semi-autonomous territory. "Greenland belongs to its people. It is for Denmark and Greenland, and them only, to decide on matters concerning Denmark and Greenland," the European leaders said, stressing that Denmark is a NATO member like the United States and is bound to Washington by a defence agreement.

The statement followed new threats from Trump. Speaking to The Atlantic last week, the US president said it was up to observers to judge what the special forces operation in Venezuela – which led to the ouster of Nicolas Maduro and his wife – might mean for Greenland. “They are going to view it themselves. I really don’t know,” he added.

WATCH MOREHow far will Trump go: Is Greenland next?

“We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security, and Denmark is not going to be able to do it,” Trump insisted, speaking to reporters aboard Air Force One on Sunday evening. “We’ll take care of Greenland in about two months … let’s talk about Greenland in 20 days,” he added.

Trump’s renewed focus on the Arctic has sparked debate in Washington and abroad. Senior US officials, including Secretary of State Marco Rubio, told lawmakers that the administration would prefer to negotiate a purchase with Denmark rather than resort to force, though the option of military involvement has not been ruled out.

02:02

Trump had already expressed a desire to annex Greenland, a vast Arctic island home to some 57,000 people, during his first term. In August 2019, he told reporters he wanted to buy the territory from Denmark, calling it "essentially a real estate deal", following reports by The Wall Street Journal on his interest in the island.

A land long sought after

The Danish province has been coveted for centuries. From the 10th century, Scandinavians began colonising the land, discovered in 982 by the Viking Erik the Red and previously inhabited by Indigenous peoples. Until the early 18th century, Norway and Denmark contested its sovereignty. In 1814, when the two kingdoms separated, Greenland remained under Danish control under the Treaty of Kiel.

Meanwhile, the United States claimed Greenland as part of its sphere of influence. Under President James Monroe’s 1824 doctrine, Washington warned European powers against interfering in the affairs of the "Americas". “From a US perspective, Greenland is North American,” Mikaa Blugeon-Mered, a geopolitics researcher specialising in Arctic regions, told FRANCE 24.

A few decades later, the United States sought to annex Greenland. In 1867, it tried to acquire the island as part of a purchase including Iceland, but Denmark rejected the offer. The US instead acquired Alaska from Russia for $7 million.

From one war to another

During World War I, Copenhagen and Washington resumed talks. In 1917, the United States purchased the Virgin Islands (formerly known as the Danish West Indies) from Denmark for $25 million to secure the Panama Canal, while recognising Danish sovereignty over Greenland.

During Denmark’s occupation by Nazi Germany, the United States invoked the Monroe Doctrine after losing contact with Greenland, which opposed any European expansion in the Americas. In April 1941, Washington signed a defence agreement with Denmark’s ambassador in the US, despite instructions from his government-in-exile. The deal allowed American troops to be stationed on Greenland, effectively turning the island into a US protectorate. Several bases were established, including Thule Air Base, now known as Pituffik.

The scramble for Greenland: Can Danish dependency resist Trump pressure?

After World War II, President Harry Truman proposed buying the island in 1946 for $100 million, but Denmark refused.

During the Cold War, Greenland proved strategically vital once again. The two countries signed a new agreement allowing the United States to strengthen its Thule base, which became a genuine US military enclave. "If there had been an exchange of intercontinental ballistic missiles aimed at the United States, they would have passed over the Arctic. That’s why they created this base, which still exists today. It is their first line of defence," said Blugeon-Mered, author of Les mondes polaires.

Politics, strategy and resources

With this long history in mind, Blugeon-Mered said he was not surprised by the US president’s recent remarks. "Trump's 2019 proposal to buy Greenland attracted a lot of attention. Journalists called me, dismissing it as absurd, though it really isn’t. The issue involves political, strategic and resource stakes," he said.

With climate change and melting ice, Greenland now sits along newly accessible shipping routes that could shorten global trade routes. In January 2025, Trump expressed concern about Chinese and Russian activity in the Arctic region.

“You don’t even need binoculars. You look outside, you have Chinese ships all over the place. You have Russian ships all over the place. We’re not letting that happen,” Trump said.

The territory, covering two million square kilometres and 85 percent ice, also contains vast mineral reserves, including rare earths – essential for smartphones, computers and electric vehicles – as well as untapped oil.

"According to the US Geological Survey, Greenland could hold hydrocarbon reserves equivalent to around 31 billion barrels of oil, roughly 15 percent of Saudi Arabia’s reserves," Blugeon-Mered said.

06:50

Accessing these resources, however, is expected to be difficult. "All foreign companies that have attempted to locate commercially viable or exploitable deposits have come up empty," the researcher added.

For Blugeon-Mered, "this geo-economic battle is becoming a geopolitical one". He added: “When China takes an interest in Greenland, it is mainly for resources; when Russia does, it is primarily about strategic chokepoints. And when the Americans or Europeans are involved, all of these factors come into play.”

Faced with such ambitions, Greenland has consistently insisted it is not for sale and wants to determine its own future. In January 2025, a poll published in the Danish and Greenlandic press found that 85 percent of Greenlanders opposed annexation by the United States, while only 6 percent were in favour.

This article has been translated from the original in French.

President Donald Trump is exploring ways for the United States to take control of Greenland, with military force “always an option", the White House said on Tuesday, raising tensions with NATO ally Denmark.

Issued on: 07/01/2026

By: FRANCE 24

Video by: Fraser JACKSON

03:02

President Donald Trump is exploring how to take control of Greenland and using the US military is "always an option", the White House said Tuesday, further upping tensions with NATO ally Denmark.

Washington's stark warning came despite Greenland and Denmark both calling for a speedy meeting with the United States to clear up "misunderstandings".

The US military intervention in Venezuela has reignited Trump's designs on the autonomous Danish territory in the Arctic, which has untapped rare earth deposits and could be a vital player as melting polar ice opens up new shipping routes.

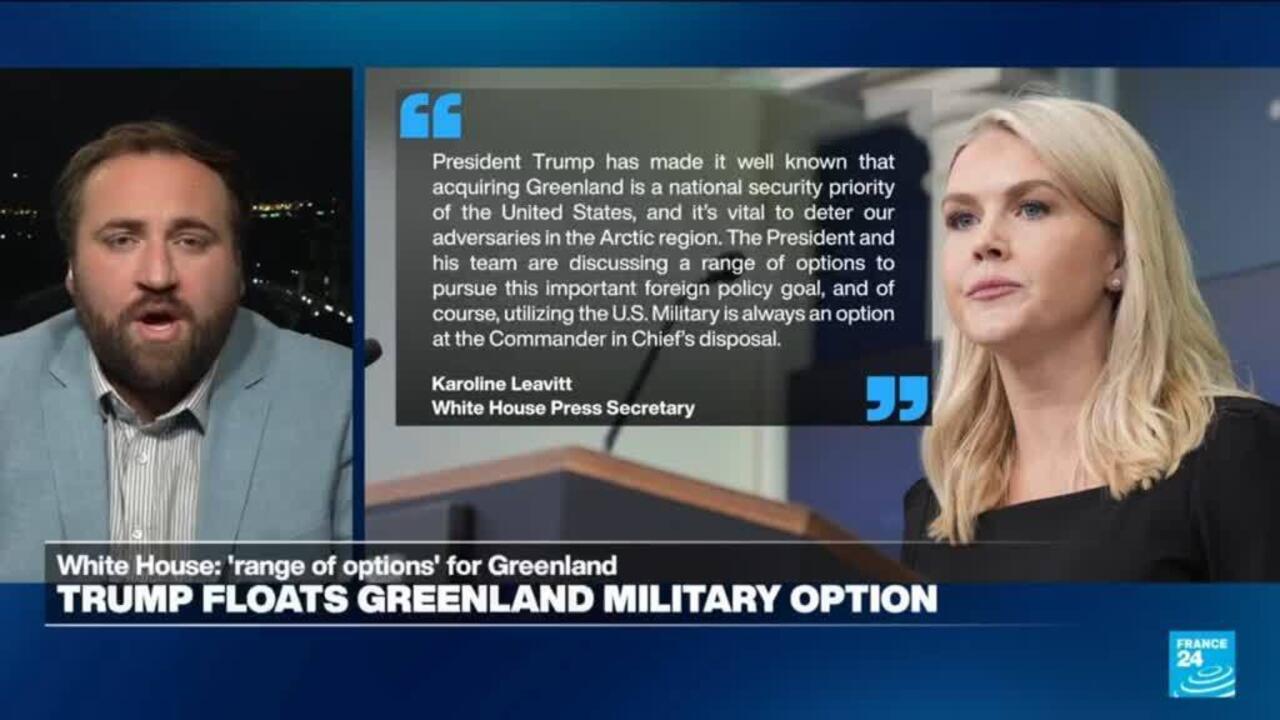

White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said that "acquiring Greenland is a national security priority of the United States", to deter adversaries like Russia and China.

"The president and his team are discussing a range of options to pursue this important foreign policy goal, and of course, utilising the US military is always an option at the commander in chief's disposal," she said in a statement to AFP.

Earlier, Greenland and Denmark said they had asked to meet US Secretary of State Marco Rubio quickly to discuss the issue.

"It has so far not been possible," Greenland's Foreign Minister Vivian Motzfeldt wrote on social media, "despite the fact that the Greenlandic and Danish governments have requested a meeting at the ministerial level throughout 2025."

Denmark's Foreign Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen said meeting Rubio should resolve "certain misunderstandings".

Greenland Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen again insisted that the island was not for sale and only Greenlanders should decide its future.

His comments came after Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Spain joined Denmark in saying that they would defend the "universal principles" of "sovereignty, territorial integrity and the inviolability of borders".

"For this support, I wish to express my deepest gratitude," Nielsen wrote on social media.

Washington already has a military base in Greenland, which is home to some 57,000 people.

Trump hinted on Sunday that a decision on Greenland may come "in about two months", once the situation in Venezuela, where US forces seized President Nicolas Maduro on Saturday, has stabilised.

'Broken record'

The European leaders' joint statement called Arctic security "critical" for international and transatlantic security.

Denmark, including Greenland, was part of NATO, it added, urging a collective approach to security in the polar region.

The statement was signed by British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen, French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk and Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez.

"Greenland belongs to its people. It is for Denmark and Greenland, and them only, to decide on matters concerning Denmark and Greenland," the statement said.

But Macron and Starmer both sought to play down the issue as they attended Ukraine peace talks in Paris alongside Trump's special envoy Steve Witkoff and son-in-law Jared Kushner.

"I cannot imagine a scenario in which the United States of America would be placed in a position to violate Danish sovereignty," Macron said.

Starmer said he had made his position "clear" in the joint statement – although he did not restate that position in front of the cameras.

Trump has been floating the idea of annexing Greenland since his first term.

"It's like a broken record," Marc Jacobsen, a specialist in security, politics and diplomacy in the Arctic at the Royal Danish Defence College, told AFP.

Trump has claimed that Denmark cannot ensure the security of Greenland, saying it had bought just one dog sled recently.

But Copenhagen has invested heavily in security, allocating some 90 billion kroner ($14 billion) in the last year.

(FRANCE 24 with AFP)

France is working with partners on a plan over how to respond should the United States act on its threat to take over Greenland, as Europe seeks to address US President Donald Trump's ambitions in the region. Denmark and Greenland say they are seeking a meeting with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

Issued on: 07/01/2026 - RFI

The White House said on Tuesday that Trump was discussing options for acquiring Greenland, including potential use of the US military, in a revival of his ambition to control the strategic island, despite European objections.

Foreign Minister Jean-Noel Barrot said the subject would be raised at a meeting with the foreign ministers of Germany and Poland later on Wednesday.

"We want to take action, but we want to do so together with our European partners," he said on France Inter radio on Wednesday morning.

Danish Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen and his Greenlandic counterpart, Vivian Motzfeldt, have requested the meeting with Rubio in the near future, according to a statement posted Tuesday to Greenland's government website. Previous requests for a sit-down were not successful, the statement said.

However, Barrot suggested a US military operation had been ruled out by a top US official.

"I myself was on the phone yesterday with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio (...) who confirmed that this was not the approach taken ... he ruled out the possibility of an invasion (of Greenland)," he said.

Trump renews Greenland ambitions

Trump has in recent days repeated that he wants to gain control of Greenland – an idea first voiced in 2019 during his first presidency. He has argued it is key for the US military and that Denmark has not done enough to protect it.

A US military seizure of Greenland from a longtime ally, Denmark, would send shock waves through the Nato alliance and deepen the divide between Trump and European leaders.

Leaders from major European powers and Canada have rallied behind Greenland, saying the Arctic island belongs to its people.

A US military operation over the weekend that seized the leader of Venezuela had already rekindled concerns that Greenland might face a similar scenario. It has repeatedly said it does not want to be part of the United States.

'That's enough': Greenland PM reacts to Trump threats

The world's largest island but with a population of just 57,000 people, Greenland is not an independent member of NATO but is covered by Denmark's membership of the Western alliance.

Mette Frederiksen, the Danish prime minister, warned on Monday that any US attack on a NATO ally would be the end of both the military alliance and "post-second world war security“.

Strategically located between Europe and North America, the US has an early warning air base in northwestern Greenland.

The island's mineral wealth also aligns with Washington's ambition to reduce reliance on China.

(with newswires)

Washington (United States) (AFP) – US President Donald Trump is considering making an offer to buy Greenland, the White House said Wednesday, despite the island's people and controlling power Denmark making clear they are not interested.

Issued on: 07/01/2026 - FRANCE24

Trump has repeatedly refused to rule out force to seize the strategic Arctic island, prompting shock and anger from Denmark and other longstanding European allies of the United States.

After a request from Copenhagen, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio said he would soon hold discussions with Danish representatives.

"I'll be meeting with them next week. We'll have those conversations with them then," Rubio told reporters.

White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said that Trump and his national security team have "actively discussed" the option of buying Greenland.

"His team is currently talking about what a potential purchase would look like," she told reporters.

Leavitt reiterated that Trump believed it was in the US interest to acquire sparsely populated Greenland, whose size is around that of the largest US state of Alaska.

"He views it in the best interest of the United States to deter Russian and Chinese aggression in the Arctic region. And so that's why his team is currently talking about what a potential purchase would look like," Leavitt said.

Neither Leavitt nor Rubio ruled out the use of force. But Leavitt said, "The president's first option, always, has been diplomacy."

House Speaker Mike Johnson, speaking as Rubio and Pentagon chief Pete Hegseth briefed lawmakers, also downplayed the potential for a US attack.

"I don't think anybody's talking about using military force in Greenland. They're looking at diplomatic channels," Johnson said.

Johnson, however, has acknowledged he had no prior notice when Trump on Saturday ordered a deadly attack on Venezuela, in which US forces removed the president, Nicolas Maduro.

The at least tactical success of the operation has appeared to embolden Trump, who has since mused publicly about US intervention in Greenland, Cuba, Iran, Mexico and Colombia.

'Stay focused on real threats'

Senator Thom Tillis, a Republican who is retiring, criticized Trump's threats in a joint statement with Democrat Jeanne Shaheen, the top Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

"When Denmark and Greenland make it clear that Greenland is not for sale, the United States must honor its treaty obligations and respect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Kingdom of Denmark," they said in a joint statement.

"We must stay focused on the real threats before us and work with our allies, not against them, to advance our shared security."

Greenland Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen has repeatedly insisted that the island is not for sale and that only its 57,000 people should decide its future.

Denmark holds sovereignty over Greenland, which has semi-autonomous status.

Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen warned Monday: "If the United States decides to military attack another NATO country, then everything would stop -- that includes NATO and therefore post-World War II security."

Denmark is a founding member of NATO and has been a steadfast US ally, including controversially sending troops to support the 2003 US invasion of Iraq.

Trump, in sharp contrast to previous US presidents, has criticized NATO, seeing it not as an instrument of US power but as smaller countries freeloading off US security.

"We will always be there for NATO, even if they won't be there for us," Trump wrote Wednesday on his Truth Social platform.

German Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul put a brave face on Trump's language on NATO and Greenland.

"I have no doubt whatsoever that we will remain closely united and that this alliance will remain exactly what it has always been -- the most effective defense alliance," he said.

© 2026 AFP

Denmark and Greenland seek talks with Rubio over US interest in taking the island

Denmark and Greenland are seeking a meeting with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio after the Trump administration doubled down on its intention to take over the strategic Arctic island.

Tensions escalated after the White House said on Tuesday that the "US military is always an option."

President Donald Trump has argued that the US needs to control the world's largest island to ensure its own security in the face of rising threats from China and Russia in the Arctic.

Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen warned earlier this week that a US takeover of Greenland would amount to the end of NATO.

"The Nordics do not lightly make statements like this," Maria Martisiute, a defence analyst at the European Policy Centre think tank, said on Wednesday.

"But it is Trump, whose very bombastic language bordering on direct threats and intimidation, is threatening the fact to another ally by saying 'I will control or annex the territory.'"

The leaders of France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain and the United Kingdom joined Frederiksen in a statement on Tuesday reaffirming that the mineral-rich island "belongs to its people."

Their statement defended the sovereignty of Greenland, which is a self-governing territory of Denmark and part of NATO.

The US military operation in Venezuela last weekend has heightened fears across Europe and Trump and his advisers in recent days have reiterated a desire to take over the island, which guards the Arctic and North Atlantic approaches to North America.

"It's so strategic right now," Trump told reporters on Sunday.

Danish Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen and his Greenland counterpart, Vivian Motzfeldt, have requested a meeting with Rubio in the near future, according to a statement posted Tuesday to Greenland's government website on Wednesday.

Previous requests for a sit-down were not successful, the statement said.

'This is America now'

Thomas Crosbie, an associate professor of military operations at the Royal Danish Defence College, said an American takeover would not improve upon Washington's current security strategy.

"The United States will gain no advantage if its flag is flying in Nuuk versus the Greenlandic flag," he said.

"There's no benefits to them because they already enjoy all of the advantages they want. If there's any specific security access that they want to improve American security, they'll be given it as a matter of course, as a trusted ally. So this has nothing to do with improving national security for the United States."

Denmark's parliament approved a bill last June to allow US military bases on Danish soil. It widened a previous military agreement, made in 2023 with the Biden administration, where US troops had broad access to Danish airbases.

Rasmussen, in a response to lawmakers’ questions, wrote over the summer that Denmark would be able to terminate the agreement if the US tries to annex all or part of Greenland.

But in the event of a military action, the US Department of Defence currently operates the remote Pituffik Space Base, in northwestern Greenland, and the troops there could be mobilised.

Crosbie said he believes the US would not seek to hurt the local population or engage with Danish troops.

"They don't need to bring any firepower. They don't to bring anybody," Crosbie said on Wednesday.

"They could just direct the military personnel currently there to drive to the centre of Nuuk and just say, 'This is America now,' right? And that would lead to the same response as if they flew in 500 or 1,000 people."

'Greenland is not for sale'

French Foreign Minister Jean-Noël Barrot said he spoke by phone with Rubio on Tuesday, who dismissed the idea of a Venezuela-style operation in Greenland.

"In the United States, there is massive support for the country belonging to NATO – a membership that, from one day to the next, would be compromised by…any form of aggressiveness toward another member of NATO," Barrot told France Inter radio on Wednesday.

Asked if he has a plan in case Trump does claim Greenland, Barrot said he would not engage in "fiction diplomacy."

Rubio to meet Danish officials next week over US interest in Greenland

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio said on Wednesday he will meet with Danish officials next week amid rising fears that Washington plans to seize the world's largest island by force.

Issued on: 07/01/2026

By: FRANCE 24

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio said he plans to meet with Danish officials next week after the Trump administration doubled down on its intention to take over Greenland, the strategic Arctic island that is a self-governing territory of Denmark.

President Donald Trump has argued that the US needs to control the world’s largest island to ensure its own security in the face of rising threats from China and Russia in the Arctic, and the White House has refused to rule out using military force to acquire the territory.

Rubio told a select group of lawmakers that it was the administration’s intention to eventually purchase Greenland, as opposed to using military force.

The remarks, first reported by the Wall Street Journal, were made in a classified briefing Monday evening on Capitol Hill, according to a person with knowledge of his comments who was granted anonymity because it was a private discussion.

On Wednesday, Rubio told reporters that Trump has been talking about acquiring Greenland since his first term.

“That’s always been the president’s intent from the very beginning,” Rubio said. “He’s not the first US president that has examined or looked at how we could acquire Greenland.”

READ MORETaking over Greenland, a long-standing US obsession

Tensions with NATO members escalated after the White House said Tuesday that the “US military is always an option”.

Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen warned earlier this week that a US takeover would amount to the end of NATO.

Rubio did not directly answer a question about whether the Trump administration is willing to risk the NATO alliance by potentially moving ahead with a military option regarding Greenland.

“I’m not here to talk about Denmark or military intervention, I’ll be meeting with them next week, we’ll have those conversations with them then, but I don’t have anything further to add to that," Rubio said, telling reporters that every president retains the option to address national security threats to the United States through military means.

01:46

Danish Foreign Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen and his Greenland counterpart, Vivian Motzfeldt, have requested a meeting with Rubio in the near future, according to a statement posted Tuesday to Greenland's government website. Previous requests for a sit-down were not successful, the statement said.

The leaders of France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain and the United Kingdom joined Frederiksen in a statement Tuesday reaffirming that the mineral-rich island, which guards the Arctic and North Atlantic approaches to North America, “belongs to its people”.

Denmark’s parliament approved a bill last June to allow US military bases on Danish soil. It widened a previous military agreement, made in 2023 with the Biden administration, where US troops had broad access to Danish airbases in the Scandinavian country.

Rasmussen, in a response to lawmakers’ questions, wrote over the summer that Denmark would be able to terminate the agreement if the US tries to annex all or part of Greenland.

But in the event of a military action, the US Department of Defense currently operates the remote Pituffik Space Base, in northwestern Greenland, and the troops there could be mobilised.

French Foreign Minister Jean-Noël Barrot said he spoke by phone Tuesday with Rubio, who dismissed the idea of a Venezuela-style operation in Greenland.

“In the United States, there is massive support for the country belonging to NATO – a membership that, from one day to the next, would be compromised by … any form of aggressiveness toward another member of NATO,” Barrot told France Inter radio on Wednesday.

Asked if he has a plan in case Trump does claim Greenland, Barrot said he would not engage in “fiction diplomacy”.

How Ukraine is shaping the European response to Trump's threats against Greenland

As Europeans seek to defend Greenland against Donald Trump's annexation threats, the fear of losing US support for ending Russia's war on Ukraine makes for a delicate balancing act.

For the past year, staying in Donald Trump's good graces has become a top priority for European leaders, who have gone the extra mile to appease the mercurial US president, rein in his most radical impulses and keep him firmly engaged in what is their be-all and end-all: Russia's war on Ukraine.

Though Europe is by far the largest donor to Kyiv, nobody on the continent is under the illusion that the invasion can be resisted without US-made weapons and come to an eventual end without Washington at the negotiating table.

In practice, the strategic calculus has translated into painful sacrifices, most notably the punitive tariffs that Trump forced Europeans to endure.

"It's not only about the trade. It's about security. It is about Ukraine. It is about current geopolitical volatility," Maroš Šefčovič, the European Commissioner for Trade, said in June as he defended the trade deal that imposed a sweeping 15% tariff on EU goods.

The same thinking is now being replicated in the saga over Greenland's future.

As the White House ramps up its threats to seize the vast semi-autonomous island, including, if necessary, by military force, Europeans are walking an impossibly thin line between their moral imperative to defend Denmark's territorial integrity and their deep-rooted fear of risking Trump's wrath.

The precarity of the situation was laid bare at this week's meeting of the "Coalition of the Willing" in Paris, which French President Emmanuel Macron convened to advance the work on security guarantees for Ukraine.

The high-profile gathering was notable because of the first-ever in-person participation of Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner, the chief negotiators appointed by Trump.

At the end of the meeting, Macron hailed the "operational convergence" achieved between Europe and the US regarding peace in Ukraine. By his side, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer was equally sanguine, speaking of "excellent progress".

But it did not take long for the elephant in the room to make an appearance.

Hard pivot

The first journalist who took the floor asked Macron whether Europe could "still trust" America in light of the threats against Greenland. In response, the French president quickly highlighted the US's participation in the security guarantees.

"I have no reason to doubt the sincerity of that commitment," Macron said. "As a signatory of the UN charter and a member of NATO, the United States is here as an ally of Europe, and it is, as such, that it has worked alongside us in recent weeks."

Starmer was also put on the spot when a reporter asked him about the value of drafting security guarantees for a country at war "on the very day" that Washington was openly talking about seizing land from a political ally.

Like Macron, Starmer chose to look at the bright side of things.

"The relationship between the UK and the US is one of our closest relationships, particularly on issues of defence, security and intelligence," the British premier said. "And we work with the US 24/7 on those issues."

Starmer briefly referred to a statement published earlier on Tuesday by the leaders of France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, the UK and Denmark in defence of Greenland.

The statement obliquely reminded the US to uphold "the principles of sovereignty, territorial integrity and the inviolability of borders" enshrined in the UN Charter – precisely the same tenets that Moscow is violating at large in Ukraine.

The text did not contain any explicit condemnation of the goal to forcefully annex Greenland and did not spell out any potential European retaliation.

"Greenland belongs to its people. It is for Denmark and Greenland, and them only, to decide on matters concerning Denmark and Greenland," its closing paragraph read.

Conspicuous silence

The lack of censure was reminiscent of the European response to the US operation that just a few days earlier removed Nicolás Maduro from power in Venezuela.

Besides Spain, which broke ranks to denounce the intervention as a blatant breach of international law, Europeans were conspicuously silent on legal matters. Rather than condemn, they focused on Venezuela's democratic transition.

Privately, officials and diplomats concede that picking up a fight with Trump over Maduro's removal, a hostile dictator, would have been counterproductive and irresponsible in the midst of the work to advance security guarantees for Ukraine.

The walking-on-eggs approach, however, is doomed to fail when it comes to Greenland, a territory that belongs to a member of both the EU and NATO.

Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has warned that the entire security architecture forged at the end of World War II, which allies have repeatedly invoked to stand up to the Kremlin's neo-imperialism, would collapse overnight in the event of an annexation. The worry is that trying to stay in Trump's good graces at all costs might come at an unthinkable price.

"Europeans are clearly in a 'double-bind': Since they are in desperate need of US support in Ukraine, their responses to US actions – whether on Venezuela or Trump threatening Denmark to annex Greenland – are weak or even muted," said Markus Ziener, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund.

"Europeans are afraid that criticising Trump could provide a pretext for the US president to conclude a peace deal at Ukraine's and Europe's expense. Is this creating a credibility gap on the part of the EU? Of course. But confronted with a purely transactional US president, there seems to be no other way."

Trump aide Miller says no one would fight US over future of Greenland

European leaders defend Greenland's sovereignty after US presidential aide Stephen Miller ramps up Trump threat to annex autonomous Danish territory.

One of US President Donald Trump's senior aides has ramped up Washington's threat to take over Greenland, stating on Monday that no one would militarily challenge the United States over the future of the autonomous Danish territory.

In an interview with CNN, Trump's deputy chief of staff for policy Stephen Miller said it was Washington's "formal position ... that Greenland should be part of the US".

His comments followed the US president's renewed call for the strategic, mineral-rich Arctic island to come under Washington's control in the aftermath of the weekend military operation in Venezuela that resulted in the capture of Nicolás Maduro.

Miller questioned Denmark's right to "control" Greenland, which is a part of its kingdom.

"The real question is what right does Denmark have to assert control over Greenland? What is the basis of their territorial claim? What is their basis of having Greenland as a colony of Denmark?" Miller said during the interview with CNN on Monday afternoon.

The top Trump aide also said the US "is the power of NATO. For the US to secure the Arctic region, to protect and defend NATO and NATO interests, obviously Greenland should be part of the US."

When asked if the US would rule out the use of force to annex Greenland, Miller said there was "no need to even think or talk about" a military operation in the Arctic island.

"Nobody is going to fight the US militarily over the future of Greenland," he said.

Miller is widely seen as the architect of several of Trump's policies, steering the president on his hardline immigration stance and domestic agenda.

EU leaders defend Greenland

Meanwhile, leaders of six European nations — Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain and the UK — issued a joint statement on Tuesday defending Greenland's sovereignty.

"Greenland belongs to its people," said the statement, which was later backed by Dutch Prime Minister Dick Schoof.

"It is for Denmark and Greenland, and them only, to decide on matters concerning Denmark and Greenland."

On Sunday, Trump doubled down on his claim that Greenland should become part of the US, despite calls by the Danish and Greenlandic leaders to stop "threatening" the territory.

"Greenland is covered with Russian and Chinese ships all over the place," Trump said while aboard Air Force One en route to Washington. "We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security, and Denmark is not going to be able to do it."

In response to those comments, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said that a US takeover of Greenland would amount to the end of the NATO military alliance.

Greenland's Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen also issued a statement in which he urged Trump to abandon his "fantasies about annexation" and accused Washington of "completely and utterly unacceptable" rhetoric. "Enough is enough," he said.

Greenland has been under Danish control since the early 18th century but gained home rule in 1979, although Copenhagen continues to oversee its foreign and security poli

The island holds vast mineral wealth, including rare earths, crucial for advanced technologies.

US Envoy Says Trump Supports Independent Greenland, Downplays Fears Of Annexation

By Magnus Lund Nielsen

(EurActiv) — An independent Greenland with close economic ties to the United States would serve Washington’s interests and need not be coordinated with European allies, the newly appointed US envoy to Greenland Jeff Landry said on Tuesday.

The remarks come as US President Donald Trump steps up rhetoric on Greenland, arguing the US “needs Greenland for defence”. On Monday, Trump’s deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller questioned Denmark’s sovereignty over the island, an autonomous territory within the Danish realm.

However, Landry – who is also governor of Louisiana – sought to dial down concerns about annexation, saying he wanted to engage directly with Greenlanders.

“The president supports an independent Greenland with economic ties and trade opportunities for the United States,” he told CNBC on Tuesday.

US officials are widely reported to be considering a Compact of Free Association with Greenland – an arrangement Washington has with Pacific island states such as Palau and Micronesia – The Economist reported this week.

Asked on Tuesday whether the US would take Greenland by force, an idea Trump has previously floated, Landry urged caution.

“No, I don’t think so,” he said. “I can’t wait to have discussions with Greenlanders.”

Landry – who has yet to visit Greenland in his new capacity – also framed the issue as an opportunity for the US, praising Trump’s revival of the Monroe Doctrine. While Greenland is part of the Danish realm, it is geographically part of North America and closer to New York than Copenhagen.

Europe pushes back

Landry’s remarks came on the same day as eight European leaders, including French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, have urged Washington to respect the territorial integrity of Greenland and Denmark.

“I would like to express my deepest gratitude for this support,” Greenland’s home-rule leader Jens-Frederik Nielsen wrote on Facebook.

Asked whether US engagement with Greenland should involve European NATO allies, Landry deflected. “I think we should ask the Greenlanders,” he said.

“I think we should ask the Greenlanders,” Landry insisted.

He also rejected suggestions that the US overtures resemble Russia’s rhetoric on Ukraine.

“When has the United States engaged in imperialism? Never,” he said.

The US envoy argued that it is rather Europe that has done so in the past, which is how Denmark gained its foothold in Greenland in the first place.

Greenland gained expanded self-rule in 2009, transferring more powers from Copenhagen to Nuuk, though foreign policy remains largely under Danish control. Both Denmark and Greenland have since embraced the principle of “nothing about Greenland without Greenland”. Direct US–Greenland cooperation that sidelines Copenhagen could therefore clash with Danish law.

Greenland By Force: How A US Takeover Would Shatter NATO And Ignite Arctic Conflict – OpEd

January 7, 2026

By Simon Hutagalung

The United States faces a significant military and strategic crisis due to its proposed acquisition of Greenland by force. The acquisition would create instability within NATO while making the Arctic region more militarised, and it would push American military resources to their limits, which could lead to a major conflict between great powers, thus damaging the U.S. ability to maintain its position as a worldwide security authority. The research evaluates military consequences which would result from this action by placing the analysis within the context of alliance relations and operational difficulties and worldwide security systems, and upholding the legal framework of the United Nations Charter and the North Atlantic Treaty.

A coercive acquisition would trigger an immediate conflict with Denmark, along with its sovereign territory of Greenland, and all NATO member states. The action would break Article 2(4) of the UN Charter because it bans any form of military force which threatens or attacks the sovereign territory of any nation. The United States would be considered a violator of international rules because it has traditionally protected the rules-based international order. The reversal would lead to worldwide disapproval, which would damage Washington’s reputation as a moral leader and might result in military clashes in the North Atlantic region.

The past demonstrates how dangerous it becomes when people perform such actions. The 2014 Russian seizure of Crimea established a precedent which showed that state violations of sovereignty would generate security problems which would lead to extended conflicts. The alliance took economic measures and enhanced its Eastern border protection while Russia built permanent military facilities throughout the Black Sea area. The 1982 Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands led to an expensive military conflict with the United Kingdom, which forced Argentina to maintain a permanent military presence on the islands while spending heavily on defence costs. The two situations show that forced land grabs create permanent military and political, and economic effects which surpass any expected strategic advantages.

The forced takeover of Greenland would harm NATO’s ability to preserve trust between its member nations. The North Atlantic Treaty contains Article 5, which requires member states to defend each other, but this provision would become ineffective when the United States faces an attack. The NATO allies would need to decide between taking action against Washington or giving up their commitment to collective defence. The alliance would experience a complete breakdown in both cases. The United States would lose international trust, which would result in reduced cooperation between nations for intelligence exchange and military training, and strategic development. The current security alliances between nations could transform because multiple countries which lose faith in U.S. actions will consider joining new defence partnerships with either the European Union or Russia, or China, which would create an unfavourable power dynamic for Washington.

The strategic location of Greenland serves as a crucial hub for all Arctic political operations. A coercive acquisition would trigger fast military expansion, which would expand across multiple surrounding countries. Russia would boost its Arctic military operations because it continues to expand its Arctic territory, while China would work to establish itself as a power that operates near the Arctic region. The United States could answer by building up its radar and missile defence capabilities throughout Greenland, but this action would create more diplomatic conflict and military competition. The Arctic region will face increasing competition for its newly accessible shipping routes because climate change has opened up these areas to navigation. The naval battles to control sea lanes would make strategic errors more likely, which would lead to an escalation of the conflict. The United States would start an unstable competition which would threaten the stability of a critical international area.

The military would face major operational and logistical challenges if it occupied Greenland. The process of securing the territory would require major military force deployments together with base construction and supply network development through the difficult Arctic environment. The extreme environmental conditions of extreme cold and ice and restricted infrastructure would create complex supply chain operations which need customised equipment and personnel training. The established requirements would redirect military resources away from different operational areas, which would lead to excessive strain on U.S. military units that currently operate across multiple international locations. The extended stay in Greenland would create an unaffordable situation, which would make it impossible to maintain military readiness in essential areas, including the Indo-Pacific region and the Middle East.

A coercive acquisition would create major security challenges which affect the entire world. The United States would experience a decline in its ability to deter because Washington would break its promise to support sovereignty and international law through its actions. International courts, together with sanctions programs, would impose legal penalties on the United States because they seek to hold U.S. military personnel and military operations accountable. The situation becomes dangerous because opposing nations could use this crisis to their advantage by having Russia and China establish themselves as protectors of international standards. The risk of great-power conflict would increase because the Arctic region would become a strategic area, which could lead nations to engage in military combat. The acquisition of Greenland would create more global instability than it would provide any security benefits to the United States.

The domestic effects of this situation would spread across all regions of the United States. The military faces potential civil-military conflicts because it needs to decide if it should follow orders which violate both military rules and ethical standards. The military will face two major challenges because service members will avoid participating in what they see as an unauthorised operation, which will harm both recruitment efforts and team morale. The congressional disagreement about this matter would create an obstacle which would block military budget approval and monitoring processes. The domestic strain would cause U.S. defence organisations to experience institutional failures, which would result in more national security risks.

The upcoming obstacles consist of various complex issues. The United States would become completely isolated because its foreign alliances would disappear, while security needs require multiple nations to work together. The Arctic region would become a new military competition area, which would require additional resources and personnel that the United States might not have enough to support. The operational challenges of military control during an occupation would exhaust all available military resources, which would reduce their capacity to defend other vital strategic locations. The domestic reaction against the United States would harm its internal power base because of political and military resistance from within the country. The problems demonstrate that the United States’ forced takeover of Greenland creates a major security risk which threatens both military capabilities and national defence strategies.

The forced takeover of Greenland would create instability within NATO while making the Arctic region more militarised, and it would push U.S. military resources to their limits and increase the chances of major power conflicts. The action would harm our national defence capabilities, while other nations would condemn us, and our military would become unable to operate as a unified force. The Constitution needs bipartisan leadership to protect its authority while preventing any actions which could result in permanent harm to national and international security.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own.

ReferencesMessmer, M. (2026, January 6). US intentions towards Greenland threaten NATO’s future. But European countries are not helpless. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2026/01/us-intentions-towards-greenland-threaten-natos-future-european-countries-are-not-helpless Chatham House

U.S. Naval Institute. (2026, January). War in the Arctic? Proceedings – U.S. Naval Institute. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2026/january/war-arctic U.S. Naval Institute

Gronholt-Pedersen, J. (2026, January 6).

Simon Hutagalung

Simon Hutagalung is a retired diplomat from the Indonesian Foreign Ministry and received his master's degree in political science and comparative politics from the City University of New York. The opinions expressed in his articles are his own.