Techno-Capitalist-Feudalism Is Malthusian to the Core!

Introduction

All rigged markets, all rigged financial-mechanisms, and, as well as, all the rigged authoritarian-structures of techno-capitalist-feudalism, indeed, did achieve their maturity in the early 21st century, through rampant surveillance, social conditioning, and data-collection. Which did prompt some political-economists to announce the effective end of capitalism in favor of a new economic system that is closer to medieval feudalism; whereupon, a centralized consortium of economic power is now firmly localized in big-tech firms, namely, those big-tech firms strewn throughout the globe and ideologically-concentrated in Silicon Valley, California.

Notwithstanding, all the way back to the early writings of the political-economists of the late 18th century and early 19th century, we can already discern the rudimentary socio-economic logic, processes, regimes, and relations, that would eventually spawn the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism. That is, the dark age which we are currently living through.

In truth, what if the aberrant mutant-capitalism we see before us right now, in the early 21st century, has always been present, dormant in the structures, processes, and the early logic of capitalism, outlined by those late 18th century political-economists. What if the end of modern capitalism was not the advent of the demise of capitalism, but, its rebirth, under a new format and/or a new feudal regime of organization aptly called, techno-capitalist-feudalism, or T.C.F. for short.

In sum, what if the old gentile, powdered-wig, pastoral-capitalism that enthralled the 18th, 19th, and 20th century political-economists, like Adam Smith and company, has merely given way to a new authoritarian form of capitalism, or more specifically, a ruthless amoral form of capitalism, closer to Thomas Malthus than to Adam Smith. Indeed, techno-capitalist-feudalism is Malthusian. It is a reflection and an expression of the Malthusian phase of capitalism, the last phase of capitalism. Thereby, techno-capitalist-feudalism is merely Malthusian-capitalism under a different name. Whereby, force and influence decide everything, i.e., all values, prices, and/or wages, strewn throughout the world economy.

In fact, from the early beginnings of political-economy and the capitalist-system, all the vital elements which would later metastasize into techno-capitalist-feudalism in the 21st century, were already present in their nascent economic-forms in the 17th and 18th century. And this includes most of the early writings of those first political-economists. Whether, it is colonialism, imperialism, monopoly, oligopoly, slavery, wage-slavery, rent, and/or an overall rigged global marketplace etc., all the ingredients for a return of feudalism, i.e., FEUDALISM 2.0, were already present in rudimentary form at the start of nascent capitalism. These rudimentary forms so prevalent in techno-capitalist-feudalism nowadays, were already exercising their coercive influence and force over the sum of socio-economic existence and the general-population, from the very beginnings of political-economy and the capitalist-system, contra what Adam Smith initially said and wrote, concerning the mechanics of the market logic of capitalism. In short, the new feudalism, i.e., feudalism redux, is a type of technological capitalist feudalism based not on lineage, title, and/or heredity, but, one based first and foremost on profit, power, wealth, rent, and private property, as well as the ruthless logic of capitalism.

Consequently, throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th century, the capitalist-system has progressively shed its gentile and gentlemanly Smithian, powdered-wig characteristics in order to reveal its true essence, a callous undemocratic ruthlessness in the procurement of economic power and wealth, by a select few ruling overlords, whose capitalist logic of operation is best exemplified in the works of Thomas Malthus.

Indeed, Malthusianism is the structure of feeling pervading the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism. And Malthusian-capitalism is the idea that force and influence decide everything, whereby, might is right, all of the time. Moreover, for Malthus, social improvement is the product of population control, the coercive control of all aspects of socio-economic existence and the general-population, including the world economy, so as to augment indefinitely the gross national product, i.e., GDP. In the sense that, according to Malthus, might, along with the profit-imperative, comprise the organizing principle, the organizing regime, and the fundamental economic drivers of the world economy, today. And, it is important to note that this has always been the case from capitalism’s very beginnings. Thus, it is accurate to state that the world economy has always been rigged, that is, a simulation of fairness and equality, without actual fairness and equality, present therein. The world market has always been a cunning simulation of economic freedom, equal market exchanges, and economic fairness, from its very inception in the 17th and 18th century, despite being the exact opposite in practice, throughout the micro-recesses of everyday life. And this fact has always been present and dormant in all markets, pertaining to the general mechanics of capitalism.

In short, capitalism has always been Malthusian to the core. The logic of predation so prevalent today, i.e., rent-extraction, appropriation by dispossession, hyper-imperialism etc., has always been a part of the logic of capitalism from the very start. That is, the logic of predation has always been a vital element in the arsenal of the logic of capitalism from the very start, as a sure means of capital accumulation. Consequently, the logic of capitalism has always possessed totalitarian aspirations. It has always embodied authoritarian characteristics in its inherent structural make-up. And these authoritarian characteristics and totalitarian processes have only metastasize over the last two centuries to become the dominant characteristics and the enslaving economic processes that are the hallmark of the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism. It is because capitalism has reached maturity and has now descended into full-blown senility that we can now clearly see and understand the Malthusian master logic, oscillating non-stop in the reactor-core of the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice. Specifically, totalitarian economic control, totalitarian behavioral modification, and pervasive social conditioning, are all types of devilish Malthusian processes undergirding the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism, like a seething Orwellian nightmare, of which Malthus would certainly approve and unconditionally celebrate. It is a nightmare, we can no longer wake up from, since, even our dreams and our sleep patterns are now fully-controlled and predetermined by the Malthusian logic, that is, the capitalist mode of production, consumption, and distribution, run-amok.

Ergo, we, the 99 percent, have become post-industrial serfs, serfs in service of all sorts of capitalist super-monopolies. And high on endless injections of Malthus, these gigantic narcotized super-monopolies, omnipotently tower over us, dwarfing us, atomizing us to the level of insignificant insects, scurrying frantically, here and there, in and across the ghoulish subterranean labyrinths of a totally predetermined and fully-supervised, super-size, global ant-colony, devoid of exit and/or any lasting hope.

I

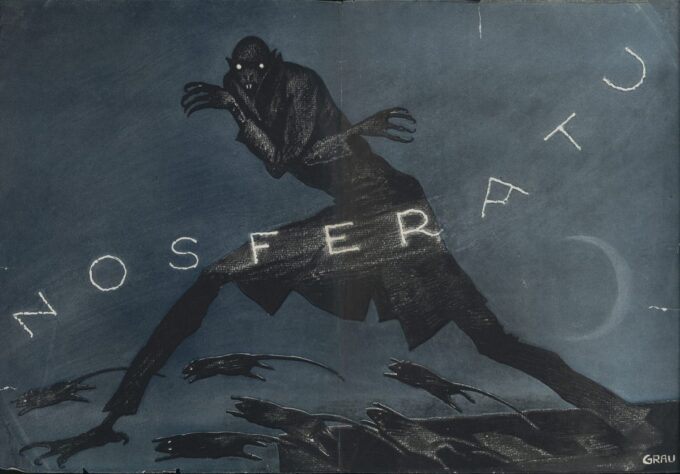

Ultimately, techno-capitalist-feudalism is a socio-economic-formation Malthus would certainly recognize, even if Adam Smith could not. In the sense that techno-capitalist-feudalism runs on Malthusian hatred, Malthusian instrumental callousness, and a deep-seated undemocratic Malthusian authoritarianism, that is full of medieval feudalist overtones, super-charged, through all sorts of fully-automated high-tech. machinery. In short, techno-capitalist-feudalism has enshrined Malthus in the software and fiber-optic cables of its very being. Thereby, the Malthusian logic of capitalism is the very atmosphere and structure of feeling, permeating the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism, infusing all of its aspects and features with an all-suffocating gothic gloom, a foreboding hopeless nihilism, i.e., a hyper-centrist neoliberal-fanaticism, which no-one can throw off and/or escape, once and for all.

According to Raymond Williams, a structure of feeling is the atmospheric mood of an era. Whereby, without articulating it, whole segments of the general-population feel and socially experience the same dreadful emotional sensations in relation to the institutions, apparatuses, processes, hierarchies, policies, and the overall economic organization of a historically specific society, without having to articulate these shared emotive-sensations among themselves. Unlike hegemony, which is predominantly and collectively ideological, a structure of feeling is “where [individual] experience[s] [and their] immediate feeling[s]…are generalized [for all]”, without needing any linguistic articulation for their emotional understanding.1 For Williams, “structures of feeling can be defined as social experiences”.2 As Williams states, a structure of feeling “is a kind of feeling and thinking [tied to a particular set of social experiences, specific to a particular era] of history”.3 Thus, according to Williams, “structures of feeling [are]… actively lived and felt. Structures of feeling [are]…structures of experience, [where] thought [is] felt and feeling [is] thought”.4 And, moreover, these structures of feeling are “the undeniable [collective] experience[s] of the present, [whereby] we may indeed discern and acknowledge [that the dominant societal] institutions, formations, positions [of an era, express a similar unconscious]…feeling”, and/or an overall collective mood, pertaining to the social experiences of the general public, i.e., the 99 percent.5 Finally, according to Williams, “differentiated structures of feeling [coincide with] different [castes]”.6 As a result, all eras of human history have their structures of feeling, i.e., those unconscious sensations felt by all, pertaining to the overall economic organization of the society. And the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism is no exception. All told, the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism is the reflection and expression of a rabid form of ruthless Malthusianism, a Malthusianism encoded into an endless set of algorithms.

Subsequently, the structure of feeling that best encapsulates the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism today is the overwhelming sense of Malthusian dread, i.e., a degenerate instrumental callousness and/or hatred towards certain types of others, that pervades and circulates throughout all these Malthusian capitalist institutions, apparatuses, and processes, as well as all the everyday lived-experiences of the general-population stationed throughout the global economy. In the sense that the general-population is more or less seen as cattle, as expendable fodder, and as raw material to be used and abused at will, by the powers-that-be, in service of greater economic power and greater levels of super-profit. In sum, the atmospheric mood that saturates the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism is best expressed by Malthus himself, in the underlying sentiment undergirding his shocking but accurate statement, that argues in favor of increased mortality rates among the working poor:

All the children born, beyond what would be required to keep up the population to this level, must necessarily perish, unless room be made for them by the deaths of grown persons. To act consistently therefore, we should facilitate, instead of foolishly and vainly endeavoring to impede, the operations of nature in producing this mortality; and if we dread the too frequent visitation of the horrid form of famine, we should sedulously encourage the other forms of destruction, which we compel nature to use. Instead of recommending cleanliness to the poor, we should encourage contrary habits. In our towns we should make the streets narrower, crowd more people into the houses, and court the return of the plague. In the country, we should build our villages near stagnant pools, and particularly encourage settlements in all marshy and unwholesome situations. But above all, we should reprobate specific remedies for ravaging diseases [so]…the annual mortality [rate could be]…increased.7

Consequently, this complete devaluation of human life, pertaining strictly to the poor, including persistent calls for increasing mortality rates among those who are poor, reflects and expresses the predominant structure of feeling of the 1 percent in the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism, namely, their total disregard for those in need, in poverty, and for those lowly workers, who have nothing to sell but their labor-power. And, according to the Malthusian logic of capitalism, everything and everyone must be conscripted by any means necessary, one way or another, into the draconian mechanical processes of uncontrolled capitalist accumulation, regardless of individual circumstances, due to the fact that the gross domestic product, i.e., GDP, requires it. Therefore, nothing must be exempt from sacrifice upon the blood alter of national GDP, a rising GDP. And, according to Malthus, the life-blood of the laboring poor, i.e., the 99 percent, must always be the first offering to appease the floundering heathen God of GDP. In the end, it is in this regard that the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism is Malthusian, in the sense that, according to Malthus, “no possible sacrifices or exertions of the rich,…could, for any time, place the lower classes of the community in a [better] situation”.8 As a result, according to Malthus, the rich are better to invest their money and their capital in profitable economic ventures that increase national wealth, i.e., GDP, than in trying to ameliorate the lives of the working poor; since, by their inherent weaknesses and inferior biological nature, the working poor are doomed to destitution and endless poverty, namely, misery and vice, regardless of their socio-economic conditions. Thus, for Malthus, it is always better to sacrifice the lives of the poor so that national GDP may live, grow, and prosper.

To quote Malthus, any “increasing wealth of the nation has…no tendency to better the conditions of the laboring poor,…or to increase [their] happiness”.9 Due to the fact that, for Malthus, “the laboring poor…seem always to live from hand to mouth [and] seldom think of the future. [Consequently,] all that is beyond their present necessities goes, generally speaking, to the ale-house; [as a result, it is necessary to avoid giving the poor higher wages, as] high wages [always] ruin…[them as] workmen” and/or work-women.10 In short, for Malthus, it is better for the rich to suppress the laboring poor, i.e., the 99 percent, since, by their inherent weaknesses and frailties, the poor invariably squander national GDP in fruitless excesses and pointless endeavors.

Subsequently, the crux of Malthus’ political-economy eloquently captures the underlying sentiment of the 1 percent, i.e., the structure of feeling, pervading and circulating throughout all the ghoulish subterranean labyrinths of the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice. That is, the vile hatred, the instrumental callousness, the anti-social tendencies, and the deep-seated undemocratic authoritarianism, which is encoded and pervades all aspects and features of the current draconian neo-feudal system, forever directed at and against the 99 percent. For Malthus, whatever the type of society, it will always be “divided into a class of proprietors, and a class of laborers, with self-love [as] the mainspring of the great machine”.11 And there is nothing that anyone can do about it, since, as Malthus argues, this is the fundamental fact of capitalist socio-economic existence. As he states, “the lower [castes] of people…shall [never] be able to provide…for [themselves or a]…family”, regardless of better circumstances.12 Thus, there will always be a small caste of proprietors managing a great majority of laborers, who themselves are trapped in perpetual misery and vice, by their own choices and devices; whereby, they will always have nothing to sell except their labor-power. But, more importantly, according to Malthus, these “great inequalit[ies] of [wealth and] property [are fundamentally] necessary and useful to society”.13 Because, they keep the poor populations and the means of subsistence in equilibrium, through vice, misery, and death. To quote Malthus,

we cannot hope for success [in improving the conditions of the poor], we shall…only exhaust our strength [and our national wealth] in [such] fruitless exertions, and remain at as great a distance as ever from the summit of our [benevolent] wishes; [and instead], we shall be perpetually crushed by the recoil of this rock of Sisyphus.14

Therefore, according to Malthus, the lives of the working poor can never be improved, as the poor are poor due to their inferior biological make-up and because a giant caste of laboring poor people is fundamentally necessary. In effect, from the Malthusian perspective, the laboring poor continually fall prey to their uncontrollable biological urges to procreate, which keeps them perpetually poor and always in need. While, in contrast, the rich are rich because of their superior biological make-up and because a small caste of rulers is fundamentally necessary; whereupon, through their superior reasoning skills, IQs, biological parsimony, and sexual temperance, they are able to amass vast amounts of wealth and capital for themselves and for the glory of the nation. In short, they are superior beings in contrast to the laboring poor.

Thereby, all great societal inequalities in-between the rich and the poor, simply permit the rich to accumulate vast amount of wealth for the glory of the nation, by allowing them to preserve wealth, rather than squander it, as the poor inevitably do. Thus, for Malthus, the necessity and usefulness of the rich is that they preserve wealth and ameliorate the productive capacities of the nation, by preventing the erosion of a nation’s wealth or GDP in frivolous activities, like philanthropy and/or benevolent poor laws, that do not work and only exacerbate misery and vice among the lower-stratums of society.

In the end, according to Malthus, the poor will always be poor and the rich will always be rich, because, it is a real “improbability that the lower [castes]…in any country, should ever be sufficiently free from want and labor, to obtain any high degree of [intelligence or] intellectual improvement”, pertaining to the procurement and preservation of national wealth.15 As a result, the political economy of Thomas Malthus supports and favors any activity, process, apparatus, organization, institution, hierarchy etc., that empowers the rich and disempowers the poor. And this Malthusian verity, concerning the superiority of the rich and the inferiority of the poor, is the central assumption undergirding the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism, informing every aspect of its totalitarian and technological development, ultimately to the benefit of the 1 percent, and, in contrast, to the detriment of the 99 percent. As Malthus states, it is simply an inescapable fact of life that the “inferior…support the superior”.16 In the sense that, according to Malthus, “some human beings must suffer,[because]… these…unhappy persons, in the great lottery of life, have [simply] drawn a blank”.17 And having drawn a blank in the great lottery of life, it is only natural that these poor souls be eternally relegated to the great caste “of people, which [solely] maintains itself entirely by [slavish] industry. [Because such a subservient caste] is [fundamentally] necessary to every [type of] state”, as its indispensable mindless workforce, capable of propping-up a small caste of superior rulers, who are the real benefit to the nation and are not a detriment to it, like the 99 percent.18

Consequently, it is in this regard that Thomas Malthus would certainly recognize the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism, even if Adam Smith did not, since, the underlying infrastructure, software, and the central-operating-code of the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice is Malthusian to the core. From alpha to omega, a Malthusian structure of feeling pervades the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice, infecting all the functions and operations of all the machine-technologies, state-apparatuses, mechanisms, organizations, and hierarchies, designed to exploit, indoctrinate, and dominate, the general-population and the natural environment in service of maximum power, wealth, and profit.

In short, the military-industrial-complex of techno-capitalist-feudalism is the embodiment of Malthusian ruthlessness. That is, techno-capitalist-feudalism is capitalism unfettered, vile and amoral. It is the Malthusian form of capitalism, run-amok, butchering itself and all global collectivities, mutual-aid communities, upon the blood altar of corporate super-monopoly, runaway fees, endless debt, debt penalties, and rent. All of which is designed to enshrine unpaid servitude as a badge of honor and a test of faith in the ultimate supremacy of totalitarian-capitalism, i.e., Malthusianism unchecked, unbound, and viscerally inhuman, ad vitam aeternam.

II

Indeed, the dark of age of TCF is dystopian and insidiously authoritarian, by means of total surveillance and pervasive data-collecting algorithms. It is an economic-system that Thomas Malthus would recognize, and, as well, encourage with joyful enthusiasm, even if Adam Smith was at a lost to do so. In the sense that, the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice is Smithian in form, but, wholeheartedly, Malthusian in content. Meaning, the overall global system is Smithian in rhetoric, but, wholeheartedly, Malthusian in praxis and ethics. Which offers an explanation, why so many people readily exclaim the end of capitalism, since, they have been cunningly massaged to believe that capitalism is Smithian; when in reality, it has always been Malthusian in practice, upon the ground floors of everyday life. Thus, having drank the intoxicating cool-aid of Smith’s invisible hand and his gentlemanly version of mom and pop, powdered-wig capitalism, it is understandable that some people would bemoan the death of Smithian powdered-wig capitalism as the death of capitalism itself, when they finally realize that the logic of capitalism does not truly follow any line of economic reasoning laid out by Smith. Genuinely disappointed that capitalism is Smithian in rhetoric only, but not in its actual practices, some individuals have started to bellow that capitalism is dead, having failed once again to notice the Malthusian snake coiling itself around the logic of capitalism, magnifying the ruthlessness of the logic of capitalism, now running wild and roughshod in and across the micro-stratums of our everyday lives.

In fact, Malthusian principles and Malthusian ruthlessness is the software and central-operating-code that pervades the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice, informing all economic mechanisms and business ventures. Of course, everywhere we see and hear Adam Smith trumpeted. Everywhere, we are told that “the best way of advancing a people towards wealth and prosperity is not to interfere with them”, especially in economic matters.19 And everywhere, we are told, by the powers-that-be, to trust in the autonomous regulating mechanism of the market, i.e., Smith’s invisible hand of the market, which directs any and all industries onwards towards the most efficient and maximizing manners of production, exchange, profit-making, and capital accumulation. Whereby, according to Adam Smith, all humans in the end are finally cared for and ultimately “led . . . by [an economic] invisible hand [to always] promote ends which where not part of [their] original intention[s]”.20 But, this is pure economic fairytale and a lullaby. And ultimately, it is sham, which is continually lulling the workforce/population to sleep and into apathy, by cunningly manipulating them to cede the sum of their political sovereignty and their decision-making-authority to the State and/or to the large-scale ruling power-blocs, which possess huge levels of economic power, capable of shackling any type of invisible hand to any type of degenerate highly-partisan directives.

Furthermore, the set of mystical properties embodied in this occult regulating mechanism, or more specifically, the invisible hand of the market, simply reflects and expresses the vast Malthusian network of ruling power-relations and/or ideologies, undergirding the overall system. Thus if, as Malthus surmises, “our present great commercial prosperity is temporary, and [the result of the]…worst feature of [the capitalist] commercial system, [namely, that its]…rising [wealth and profits only augment] by [means of] the depression of others”; then, it should come as no surprise to anyone, that the rising economic inequality nowadays in-between the 1 percent and the 99 percent is a direct result of the rise of Malthusian capitalist super-monopolies, i.e., those giant monopolies inspired by Malthusian principles and Malthusian ruthlessness.21

In sum, techno-capitalist-feudalism functions and operates by means of Malthusian principles and a Malthusian economic ruthlessness. That is, it functions and operates by means of a series of Malthusian zero-sum-games; whereby, the same economic winners of the game of capitalism must be continually off-set by the same economic losers, over and over again. In short, thousands must be rendered destitute or homeless in order to manufacture a single billionaire. And such a gruesome economic-system can only be Malthusian to the core. So forget Adam Smith, because to defeat capitalism, capitalism as it really is, i.e., Malthusian, it is necessary to defeat and demolish Thomas Malthus, the father of the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice, namely, the first systems’ engineer of the dark age of techno-capitalist-feudalism. As Malthus states, “all monopolies yield high profits”.22 Thereby, all business ventures, whatever they may be, must strive for monopoly power or oligarchic power, whereupon, the maximization of capitalist profit, wealth, and power, by any means necessary, at the lowest financial cost, as soon as possible, is ultimately assured and guaranteed, ad infinitum. In the sense that monopoly power, or oligarchic power, guarantees that any capitalist enterprise, which possesses monopoly power or oligarchic power, will always be privy to massive revenues and super-profits, due to the advantageous circumstances of them having huge levels of force and influence over the world market, commodity prices, and the general-population. And, in contrast, large segments of the general-population must inevitably fall into pauperism so as to accommodate the pressing needs of these super-monopolies and/or oligopolies, attempting to amass super-profits, as well as, greater levels of economic power for themselves. In short, super-monopolies add to the general wealth of the nation, i.e., its GDP, while, the general-population does not and only subtracts from it.

Therefore, according to Malthus, the masses are constantly “being placed in a situation in which the growing prosperity of [super-monopolies is a]…signal of [their] own approaching ruin”, and this is done by design and not by random accident, as all zero-sum-games are fundamentally Malthusian in the end. That is, they are the consciously planned product of the Malthusian logic of capitalism, rigged in favor of the 1 percent.23 Ergo, all rising wealth and/or super-profits require the pauperization of the masses, without exception. And this is a fundamental rule and/or an axiom of Malthusian-capitalism, i.e., techno-capitalist-feudalism, namely, that we must have the pauperization of the masses, alongside the constant enrichment of the ruling oligarchy or aristocracy, so as to effectively augment national GDP. In the sense that a superfluous segment of the workforce/population is needed in order to keep wages artificially low. And ultimately, this underlying economic principle of techno-capitalist-feudalism is directly derived from Malthus, and not from Adam Smith. Thereby, to quote Malthus, this central economic principle of techno-capitalist-feudalism, i.e., that the pauperization of the masses is necessary, “is the [fundamental] reason why so many noble efforts in the cause of freedom have failed, [when it comes to the laboring poor], and why almost every [socialist] revolution, after long and painful sacrifices, has [always] terminated in military despotism”; because, regardless of the type of revolution, it is inevitable that a small caste of rulers will govern over and against a large caste of commoners and/or serfs, regardless of the type of revolution and/or socio-economic circumstances.24

As a result of this ruthless principle, according to Malthus, it is best that societies put their trust and financial resources to good use through a small caste of ruling capitalists, rather than to throw their financial lot with the laboring poor; since, “indolence and improvidence…prevail among …[ these laboring poor] people. [In the sense that these poor] peasant[s]…[have] not been [groomed to have any type of lasting]…industrious habits”.25 Ultimately, according to Malthus, the laboring poor are lazy and shun industrious work, every chance they get. Thus, any precious resources directed at benevolence and alleviating poverty among the laboring poor will be squandered away in all sorts of fruitless endeavors, initially designed to help these poor people. In short, for Malthus, the poor have too much money and power, while the rich have too little money and power. Therefore, it is imperative to create and implement a series of state-policies and Malthusian traps that continually reverse this uneven polarity of wealth and power in-between the 1 percent and the 99 percent, in favor of the 1 percent. Due to the fact that, it is only the 1 percent that augments the power of the nation and national GDP. While, in contrast, the poor only erode the power of the nation and national GDP, through their irresponsible and lazy habits.

For instance, to quote Malthus, in any type of advanced capitalist society the most important people are to be found in financial speculation; that is, it is “the man [or woman] who is [prone to constant]…speculation [that] is a positive and decided benefactor to the [nation] state”.26 In sum, it is these titans of finance, through their many speculative ventures, that drive economic progress forward and permit individual nations to augment their productive capacities and Gross Domestic Product, through their many speculative investments. While, according to Malthus, the laboring poor only subtract from the nation and national GDP, due to their insatiable, ravenous, and unchecked needs, including their overall general laziness.

Consequently, in the dark age of TCF, Malthusian principles and Malthusian ruthlessness rule. Meaning, all economic intentions in the dark age of TCF are Malthusian, despite paying homage to Smith’s Wealth of Nations, verbally and rhetorically. That is, the general framework of techno-capitalist-feudalism is roughly configured according to the political-economic framework of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, but, the intentions, practices, mechanisms, and ethics, behind the political-economic framework of techno-capitalist-feudalism are Malthusian to the core. In fact, all sorts of shady Malthusian elements and economic traps inform the mechanisms and features of the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice, whereby, they are all fundamentally designed and re-designed to empower to the 1 percent and disempower the 99 percent, just as Malthus prescribed in the early days of capitalism at the beginning of the 19th century. To quote Malthus, “a [rich] person who contemplates the state of the lower [castes] of people…would [be advised]…to retain them forever in that [lowly depraved] state, by preventing the introduction of [affordable] manufactured [goods] and luxuries [for them]”.27 In this manner, he or she would keep the lower castes of laborers stationary, subservient, and forever in bondage, as an industrial army of cheap laborers, willing and ever-ready to lend a helping hand to their capitalist social betters, stationed higher-up upon the social Darwinian wealth-pyramid.

Ergo, for Malthus, such economic ruthlessness towards the lower castes of society is fundamentally necessary. It is a necessary evil, in the sense that “evil exists in the world, not to create despair, but [industrious] activity”, especially among the laboring poor.28 In other words, according to Malthus, the laboring poor lack industriousness; they are “ inert, sluggish, and averse [to] labor, unless compelled by necessity”.29 Hence, it is the task of all rich capitalists to spur them onwards, towards ever-increasing productivity, so that the glory of the nation and national GDP may be magnified annually, progressively, and unconditionally.

In the end, techno-capitalist-feudalism may have evolved beyond Adam Smith in various ways, but it has not evolved beyond Thomas Malthus, who being the first to theorize about the ruthless logic of zero-sum capitalism, namely, unfettered inhuman neoliberal-capitalism, out of control. Thereby, the dark age of TCF, is Malthusian to the core. And, in fact, techno-capitalist-feudalism marches on towards ever-higher forms of hyper-Malthusianism, as the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice descends deeper and deeper into the deathly morass of evermore powerful, evermore authoritarian, and evermore refined forms of capitalist-totalitarianism. That is, an authoritarian form of capitalism, a Malthusian-capitalism, a totalitarian-capitalism that is directed squarely above and against the laboring poor, i.e., the 99 percent, ad infinitum.

Conclusion

In sum, techno-capitalist-feudalism has barbaric tendencies. It is Malthusianism, run-amok. And, as an all-encompassing totalitarian-system, techno-capitalist-feudalism readily destroys the land of resources and fleeces the people of their personal information and labor, without remuneration and/or any type of equivalent exchange. In the sense that the growth of the productive forces and national GDP require it and are only speedily improved by such draconian Malthusian methods. Bottom-line, techno-capitalist-feudalism is Malthusian predation to the maximum and beyond, without any regards for the well-being of the 99 percent. Whether this is imperialism, colonialism, barbarism, creative-destruction, runaway debt-peonage, rent, war etc., Malthusianism pervades the software of the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice. And Malthusianism always commands the total curtailment and immobility of the laboring masses forever upon the lower-stratums of the system, via rampant authoritarian forms of population control. In the sense that through stringent population control, exercised at the micro-levels of everyday life, the techno-capitalist-feudal-edifice may achieve an ever-increasing annual GDP and national glory, as well as its own continuous systemic betterment throughout.

Consequently, techno-capitalist-feudalism concerns itself, first and foremost, with maintaining the overall supremacy of a set of Malthusian multi-national super-monopolies over and against the global citizenry, which itself, is scattered, atomized, disillusioned, and increasingly impoverished in and across the globe. At its most basic, techno-capitalist-feudalism functions and operates to maintain, safeguard, and expand, super-monopolies in and across the global economy, insuring their dominance over the workforce/population by keeping the workforce/population, i.e., the 99 percent, forever in financial bondage and in poverty, due to the fact that, according to Malthus, every type of society requires huge masses of the laboring poor in order to effectively function and operate, smoothly; since, the laboring castes are “the foundation on which the whole [social] fabric rests” and is woven together, as one terrifying mental and physical draconian ensemble.30

Thereby, the laboring poor must remain forever upon the lower stratums of the system, without opportunity or chance of ascendancy, so that the maximization of national wealth, i.e., national GDP, may continue to augment and progress, unabated. Ultimately, the truth of the matter is, according to Malthus, that the laboring poor can never escape from misery, vice, and/or death, regardless of philanthropy and/or human benevolence, as “death [and] pain [among the laboring poor] is absolutely necessary”, for any type of socio-economic improvement to occur and/or for any type of civil society to exist.31 As a result, from the Malthusian perspective, it is an inescapable fact of life in the dark age of TCF, that huge bulbous masses of laboring poor must exist and be continually manufactured, by the titans of super-monopoly, so as to keep our global capitalist society afloat and moving onwards, towards ever-heightened levels of technological development and GDP.

So, indeed, techno-capitalist-feudalism has shed the gentlemanly, powdered-wig, pastoral-capitalism of Adam Smith and revealed itself to be pure economic ruthlessness, namely, Malthusianism unfettered, the callous inhuman horror of totalitarian-capitalism, rabid and foaming at the mouth. In short, techno-capitalist-feudalism is the first economic system in history that has fully-shed its Smithian exoskeleton so as to reveal its true economic essence, its true economic nature, stretched-out and fully-bloomed, i.e., a dark totalitarian-Malthusianism, an all-consuming wickedness, avarice, a pathological economic madness, gone berserk. That is, a terrifying multiplying hydra, ghoulish and gory, without flesh and without legs, slithering the four corners of the earth, ravenous and un-dead, monstrous and insect, a buzzing litany of devilish heads protruding, gigantic, out of its giant mammoth neck, devouring our best, and leaving grim death to claim the rest, all those fleshy meaty leftovers, diced and sliced, and piled-on high, atop of the medieval capitalist gut-wagon.

ENDNOTES:

1. Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature, New York: Oxford University Press, 1977, p. 129.

2. Raymond Williams, p. 133.

3. Raymond Williams, p. 131.

4. Raymond Williams, p. 132.

5. Raymond Williams, p. 128.

6. Raymond Williams, p. 134.

7. Thomas Malthus, An Essay On The Principle Of Population, London, U.K.: Reeves and Turner, 1878, p. 411-412.

8. Thomas Malthus, An Essay On The Principle Of Population And Other Writings, UK: Penguin Books, 2015, p. 118-119.

9. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 135.

10. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 44-45.

11. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 90.

12. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 119

13. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 123.

14. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 145.

15. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 95.

16. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 157.

17. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 89.

18. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 68.

19. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 254.

20. Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations: (Book I–III), London: Penguin Books, 1999, p. 24.

21. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 206.

22. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 205.

23. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 208.

24. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 193.

25. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 276-279.

26. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 181.

27. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 144.

28. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 163.

29. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 151.

30. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. xxv.

31. Thomas Malthus, 2015, p. 162.