The administration’s pre-emptive assault on history is a desperate attempt to stop new social movements from starting.

By Nicholas Powers ,

The Slavery and Freedom exhibit at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in D.C. is a soul-shaking experience. Going from the bottom level to the higher exhibits, visitors take the journey from slavery to freedom. I went years ago, and decided to go again with family and friends. During the government shutdown, the closed museum doors were symbolic of a larger right-wing attack. Donald Trump and the MAGA movement have censored Black history, pulled Black books, removed Black Lives Matters icons, and led to a mass firing of Black federal employees.

The right wing suppresses Black history because it ignites social movements. Black history transforms rage into activism by putting racist events into a larger story of struggle against oppression. It shines a light on a hidden past. It exposes the hypocrisy of MAGA.

The right-wing attack on Black history is stupid, cruel, and futile. The logical end of censoring Black history is national suicide. Black history is a legacy with lessons that can heal the divides in the U.S. and repair our relationship to the world. Black history can free us from the right-wing image of the U.S. as a white Christian nationalist utopia, which never existed, and lead us to a clear-eyed radical realism. Black history bears a truth that makes it possible, finally, to create a future we can live in as liberated beings.

Trump’s War on Black America

Related Story

Interview |

Black History Testifies to the Impossible Creative Power of Black Resistance

Literary scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin discusses how Black yearning keeps surviving in the face of racist violence. By George Yancy , Truthout February 23, 2025

Trump and MAGA are waging war on Black America. They have attacked it on three fronts; Black culture, Black economics, and voting rights. The attack on history is the most dangerous, because history gives birth to new protests.

Black history bears a truth that makes it possible, finally, to create a future we can live in as liberated beings.

In March, federal workers aimed jackhammers at the Black Lives Matter mural — blocks from the White House — and destroyed it. Less than a mile away, the African American Museum of D.C. was closed during the shutdown and has only recently reopened.

Trump came out the gate of his second presidency with a barrage of executive orders. One executive order titled “Ending Racial Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling” led to Black-authored books being yanked from school libraries run by the Department of Defense. Trump shut down diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs. He terrified business leaders with possible DEI investigations. Black history month celebrations were cancelled at federal agencies.

In a perverse kind of trickle-down racism, Trump’s attack on Black Lives Matter became a permission structure for increased on-the-ground bigotry. White influencers proudly wore blackface for Halloween. Politico exposed a Young Republicans’ chat where they gleefully traded racist comments. Black comedian W. Kamau Bell has painted a portrait of a right-wing shift in standup performances in which anti-trans jokes and anti-Black slurs have become commonplace. This is not a series of isolated events: FBI statistics on anti-Black hate crime, consistently the most common form of hate crime, spiked during Trump’s two terms.

Side by side with the cultural attack is an economic one. Remember Elon Musk proudly waving a chainsaw at CPAC? Well, it worked. Black women’s unemployment leapt from 5.9 percent in February to 7.5 percent in September. Trump’s cuts to the federal workforce and attacks on “DEI” forced 300,000 Black women out of their jobs. Put that number next to the 2003 statistic that 64 percent of Black families are led by a single parent, most of whom are single mothers, and the effects are devastating. Women are now trying to hold families together without work or health care.

When seen in that light, a closed history museum may seem to be at the bottom of the list of things to worry about. Yet a living relationship to history has the power to create a political consciousness for resistance. The ripping up of Black Lives Matter’s art, the censoring of Black books, the effort to whitewash Black history — all are part of a desperate attempt to stop a new social movement before it starts.

The Past Transforms Us

Emmett Till’s casket was right there, and no one could speak. I stood with visitors to the African American Museum in D.C., and the “Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom” exhibit that highlights the Civil Rights Era weighed on us. To be in the presence of history, to be inches away from the casket that Emmett Till lay in, was dizzying.

The ripping up of Black Lives Matter’s art, the censoring of Black books, the effort to whitewash Black history — all are part of a desperate attempt to stop a new social movement before it starts.

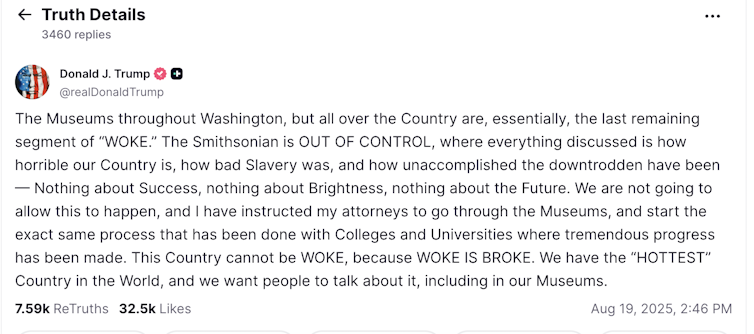

Trump actually visited the museum in 2017 and in a somber tone, said, “This museum is a beautiful tribute to so many American heroes, heroes like Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass.” Eight years later, in August 2025, Trump posted on Truth Social, “The Smithsonian is OUT OF CONTROL, where everything discussed is how horrible our Country is, how bad Slavery was…” Well, that’s a 180-degree turn.

Why the change? Two events upset Trump’s first term: COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter. Protests against police brutality have been ocean tides in the Black Freedom Struggle, of which BLM is the most recent wave.

Black protests against police brutality go far back. We see it in Abolitionists fighting the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and we see resistance in the Red Summer of 1919. Racist brutality sparked the Harlem riots of 1935 and 1943. In 1991, the police beating of Rodney King led to the L.A. riots. In 1999 the police murder of Amadou Diallo and the 2006 killing of Sean Bell launched marches. Wave after wave reached higher and higher. In 2020, BLM became a tsunami of protest, the largest in U.S. history — and it was also strong enough to carry voters to the polls and throw Trump out of office.

The Black Freedom Movement has more power than any president or any system. Trump knows this. MAGA knows this. This is why they erase Black history. The past transforms us, it fires up dormant desires. It realigns us with our ancestors. Black artists and intellectuals always documented the dramatic effect of learning about Black history.

Assata Shakur wrote in her 1988 autobiography, Assata, “I didn’t know what a fool they made of me until I grew up and started reading real history.”

Malcolm X wrote in his 1965 classic, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, “History had been ‘whitened’ in the white man’s history books and the black man had been brainwashed for hundreds of years.”

From Frederick Douglass to Dead Prez, Ida B. Wells to Alicia Garza, knowing one’s history has always been the key ingredient to activating Black consciousness.

The Black thinker who systemized this transformation is Dr. William E. Cross in his 1971 essay, “The Negro-to-Black Conversion Experience.” Cross had a front-row seat to the 1968 climax of rebellion. He repeatedly saw apolitical brothers and sisters sparked by the revolution; they shed old lives, old fashions, and old ideas, and re-emerged in the street, wearing afros and bright pan-African colors. They went through stages like a butterfly molting in a cocoon, flying out, free as themselves.

Black history is the cocoon; it is the stories and imagery, the feeling of ancestors, it is the site of transformation. When millions upon millions undergo that change, like during the George Floyd protests, it becomes a historical force. A meteorologist, trying to show how interconnected all things are, once said that a flap of a butterfly’s wings can set off a tornado. It’s true. Why? The more that racists try to repress our history, the more we use it to explain what is happening, and how to fight back. The next social movement is already beginning, like a tornado.

As Pressure Builds, More Will Find Our History

When I finished my tour of the African American Museum, I was at the top floor. Sunlight came through the windows. The building is designed to recreate the journey from slavery to freedom. Standing at the top, I felt deeply moved.

Black history is the cocoon; it is the stories and imagery, the feeling of ancestors, it is the site of transformation.

The power of history, especially at a museum, is that right there under glass is evidence of our past. Flesh fades to dust. Bones crumble. Yet here are real things touched by real people. This is why the African American Museum in D.C. is the crown jewel of a large network of Pan-African historical sites. In New York, there’s the African Burial Ground. In Boston, there’s the Black Heritage Trail. In Tennessee, there’s the National Civil Rights Museum. In Ghana, there are slave castles and the heart-wrenching Door of No Return. The interconnected network of sites creates multiple transformation zones, where people enter and come out changed. When we leave, we take this history with us.

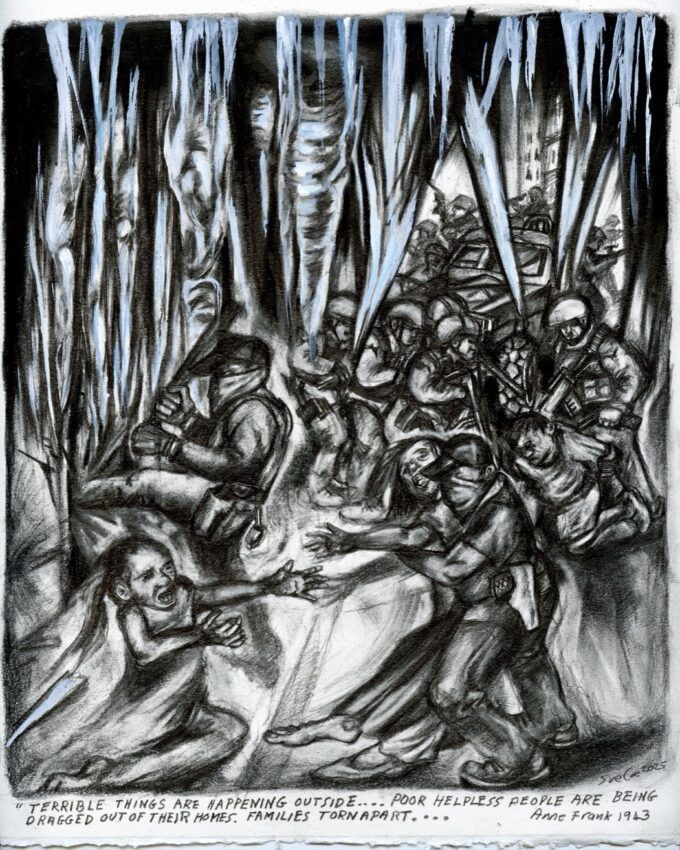

The tragedy of this moment is that Trump and MAGA have succumbed to a juvenile, cartoon version of history. If they turn back time, they believe, the joy of unlimited power will be at their fingertips. The harder they push for total control, the more pressure they place on masses of people. The government shutdown worsened hunger. People in the U.S. are facing even more unpayable health insurance. Rage at ICE builds in neighborhoods as masked agents separate families.

Under this pressure, many are forced to ask questions. When they do, they will find answers waiting for them. They will find our history.

Expect more tornados to come.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

Nicholas Powers

Nicholas Powers is the author of Thirst, a political vampire novel; The Ground Below Zero: 9/11 to Burning Man, New Orleans to Darfur, Haiti to Occupy Wall Street; and most recently, Black Psychedelic Revolution. He has been writing for Truthout since 2011. His article, “Killing the Future: The Theft of Black Life” in the Truthout anthology Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? coalesces his years of reporting on police brutality.