We distinguish the announcements of the soul, its manifestations of its own nature, by the term Revelation. These are always attended by the emotion of the sublime. For this communication is an influx of the Divine mind into our mind…In these communications the power to see is not separated from the will to do, and the obedience proceeds from a joyful perception.

– Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Oversoul

We live in a very low state of the world, and pay unwilling tribute to governments founded on force. There is not…. a sufficient belief in the unity of things to persuade [men] society can be maintained without artificial constraints. Strange too, there never was in any man sufficient faith in the power of rectititude to inspire him [to renovate] the State on the principle of right and love…on the simple ground of his own moral nature.

– Emerson, Politics

I’m looking at the different ways people use to deal with rising levels of anxiety, even terror, in the current context of rampant insecurity affecting everyone except maybe the billionnaires. They- the billionnares – can limit their worry to the next Luigi Mangione or, more lawfully, to the rise of a smart social democrat like Zohran Mamdani, and it would be pleasant to imagine they do. But looking at this, and the fact it’s fully reasonable people would seek after some sort of relief, it’s not surprising there’s such an array of industries organized to meet the need for narcotization.

I’m being neither sarcastic not provocative for its own sake in suggesting we perhaps need to re-evaluate that once popular narcotic that has fallen so far out of favor – not, I hasten to add, to interest people in taking up smoking, but to appreciate more fully the underlying terror, coming before threat of nuclear war, before threat of mass extinctions, before mass shootings and rising fascism, way before Donald Trump, that, unaddressed and unaccounted for leaves people with no way to think other than along the same old channels; in other words, that leaves the liberal world with no way out of conformity. I’m speaking of existential terror, in the soul, which is mainly unaddressed and untreated; practically, it leaves a vacuum in which menacing forces can grow stronger unopposed. That is, without a “counterforce” of identity pinned to a higher or wholer vision, threats from outside – particularly for those of us contained in reassuring liberal reality – while we worry about them plenty, at the same time they never are real: “not in my lifetime, not in my neighborhood, not in my world,” etc.

I bring up, for evidence, the signs that proliferate on well-tended lawns in the nearby college town of Clinton, proclaiming“Hate Has No Home Here,” expressive of a certainty that could exist, I feel, only in imaginations that have not allowed too-close horror to be included. Likewise, statements such as “I can’t believe this is happening in my country,” or, “this is not my country,” betray a delusional distance from evil which comes not just from ignorance of history, but from lulled or “canceled” imaginations, the lack of capaciousness of mind that allows for evil to be known – in one’s own consciousness – as real.

The real existence of evil is in the very denial of it. There could not be such certitude about hate’s “home” being elsewhere unless something were being denied. I argue that something is terror left in the soul by trauma, no longer limited to extraordinary cases of abuse or wartime (which of course were not extraordinary for the majority of people in history). It arises out of modern, strictly rationally-based thinking and the capitalism-syntonic, me-first, isolating lifestyle that no longer can imagine being (only doing). Thus, crucially, people fail to imagine the radical, uncompromisable need of infants for safety not just from accidents but in their beings that require, animal-like, constant, excessive reassurance of warmth from human contact. Such constant reassurance, conventional, logical “wisdom” tells us, is plain impossible given the economic reality in which we make our lives. Perhaps so, given all the exceptions to constancy of direct physical, non-conflicted care that now are normalized, from violence and wartime conditions mainly affecting underclasses, to abusive or neglectful parenting, to even well-informed by-the-book liberal parenting. Nevertheless, the consequence is trauma, as inescapable an aspect of human biological life now as dioxins in mothers’ milk and an effective means of normalizing the illusion of innocence.

Repressed, as trauma must be, it transforms into that “closed door” in the mind that, in fairytales, the hero is forbidden to open. A society reading fairytales in order to keep itself awake to the real, mythic forces at work, might offer some clue as to what’s to be done! But in a society in which imagination is not real, trauma denied, the shadow area becomes disproportionately terrifying. This terror makes monsters out of some, deluded liberals of others, the “center cannot not hold.”.

For conformity is universal, and it’s socially acceptable. And, with religion out of fashion, gone is the possibility given in belief – that nonconformity on behalf of a larger good is also universal, given in the soul (in imagination). As Emerson’s teaching is evidence for, or Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, or Gandhi’s, the soul’s orientation is up “high” toward goodness, truth, beauty; hence the popularity of the means for numbing it – the substances, activities, distractions – are incredibly effective for suppressing dissent, preventing honest disruption to the status quo. Some of such means are less obviously destructive than others. But in the soul, all have the same effect and must be judged accordingly; no matter to what “good uses” we may put them nor how completely normalized they’ve become, nor how much we need them to keep the economy going they inhibit the priceless experience of unmediated joy that is “the influx of the Divine mind into my mind.”

To be less the creatures of our habits of numbing and narcotizing, judgment will have to be widened to include our way of life, for that is what we numb against! Only the sovereign soul is capable of making such a radical judgment, and it only is capable of the “perception of joy” that makes obedience to it – rather than to the overwhelming power of conformity – as natural as following heart’s desire.

+++

Every once in awhile, a situation arises in which I have to confess to somebody – such as a bank official, or some customer service representative trying to help me change a password – I do not have a mobile phone. I make no assertive announcement of it; I am all too aware of how my choices have severely limited my life in ways I still struggle to accept. But as well, the severe limitation, like being mute or deaf, gives me an unusual perspective from which I may as well speak, as if my lifestyle choice were at very least, my right, and, possibly, my duty to the soul’s truth! Not invariably, but it still happens sometimes that the person I’m speaking with responds, almost automatically, as happened recently, “Good for you.” But they never say more, and today I’m realizing I really really want to know: Do they truly think there is something admirable in holding out against having one of these devices when every person under the sun, across the globe, 15 years of age and over, rich and poor, has one? When practically every agency, business and customer service one has to deal with in life expects you to have one, to be able to use QR codes, and to tell friends who don’t have a doorbell you’ve arrived at their door? After President Obama, realizing they were now as basic a need as food, water, or electricity, made them available for people who otherwise couldn’t afford them?

Why, given all this reality, do they say those words a part of me longs to hear: “Good for you!” Do the words come from their soul, I wonder? For, surely, their soul has her reservations! Have they accepted a resignation about it as we must do about so many practices we know are not good for either social or biological environment or both? In some people the resignation is real – they manage their phone use like a social drinker manages her drinking – gotta participate, but in moderation. But in many others, there is no moderation. To return to the comparison with smoking: we no longer have to worry about Joe Camel, but should we not worry that the same motivations that drove the tobacco industry also drive the social media industry, and thus the same unconscionable tactics, preying upon peoples’ weaknesses, will be used? And would we allow this to happen if we feared loss of soul as we do weight gain or end of life?

+++

When Emerson preached against conformity in preference for “self reliance,” or self-trust, he knew that failure to escape from conformity meant men could never be inspired to deny “the authority of the laws” on “the principle of…love.” My interest is not to rant against social media, or the new internet-based consumer world, though as I said, I’m in a unique position to critique it because I’ve abstained, maybe from warped principle, or maybe because the phone use that has invaded my social environment enhances my feelings of discardability. Unlike smoking behavior, which still allows for eye contact and words exchanged, screen-watching feels to a non-participant almost passive aggressive, my presence unwanted. Even so, I do not make futile war on screens. My “war” is against social conformity, from which to my mind there is no effective weapon except a sovereign demand for peace attainable for those whose first devotion – by means of creativity – is to the radically extreme, “sublime emotion” of joy.

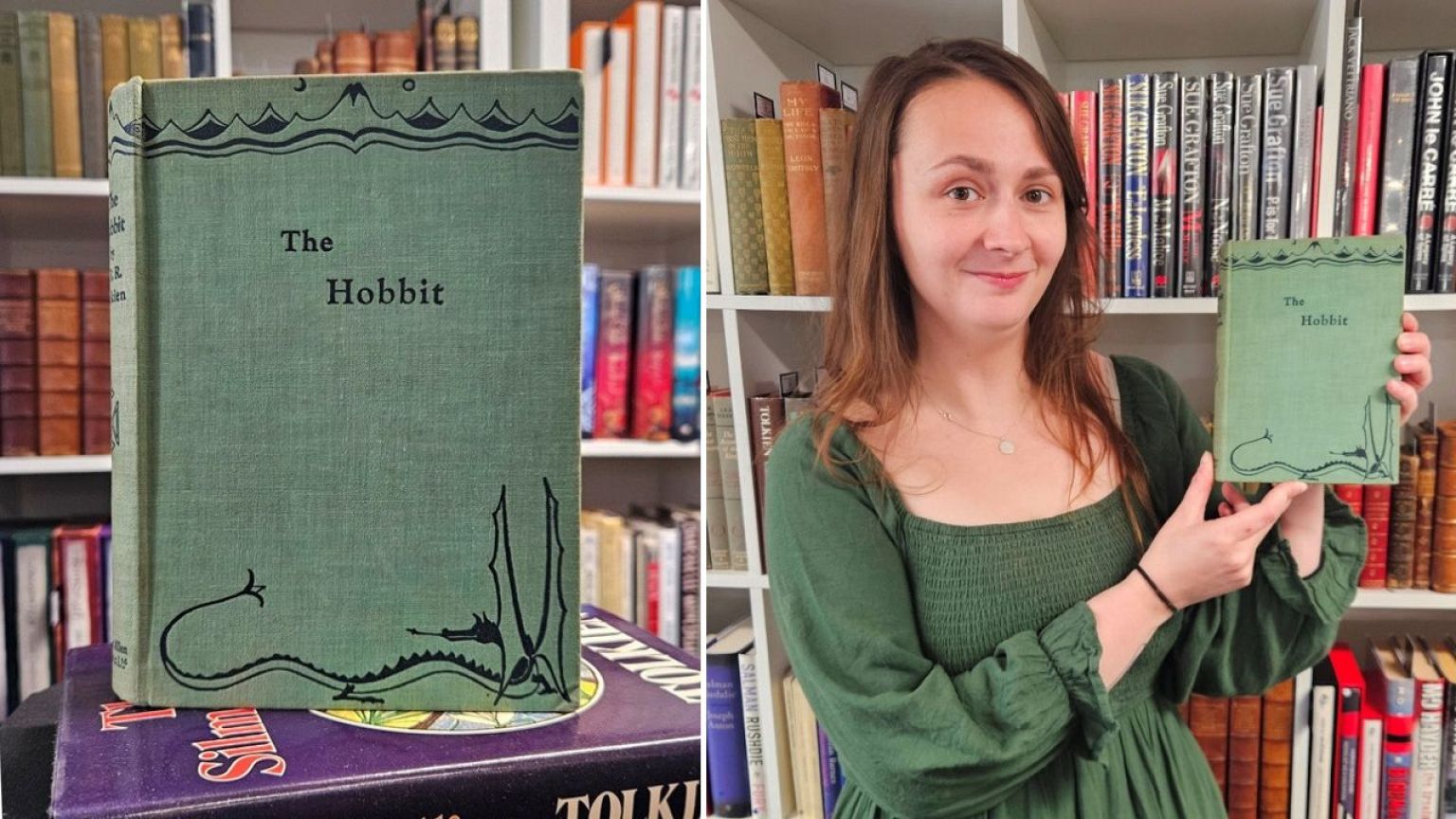

Nobility, honor, duty – those attributes that draw so many people to the great myth-based stories that emerged in popular movies as if specifically to get us thinking about those heroic qualities: Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, many prequels and sequels – how am I to understand them – as just grand adventures for my entertainment? Worse, are they to be left to be taken seriously (as I read recently) by Trumpist billionnares, providing reinforcement for their certainty- or at least of the banner they wave in front of their Christian supporters – of theirs being the good side fighting the bad guys trying to replace us? We can say this is nonsense, but at the same time, fascism gains ground and the liberal left does not.

Or might the powerful attraction of these stories have possible reference to a different realm for heroism in the post-modern reality? In The Lord of the Ring, the protagonist hobbit Frodo – against the staunch opposition of his most loyal comrade, Sam Gamgee, includes the untrustworthy and loathsome Gollum in their quest to fulfill the larger purpose of the Ring that includes all the kinds of inhabitants of Middle Earth – elves, dwarves, hobbits, men. In contrast, the liberal left, having dropped its sword of discernment in favor of security at any cost, merely knows it is against evil – “Hate has no home here.” When inclusive “God” reality, from which even evil is not excluded, remains exiled in the unconscious, the dark side wins.

Recently I watched The Scarlet and the Black (1983), a movie about the heroic actions of a Vatican priest during the Nazi occupation of Rome that began in 1943. Like many other people, my simplified understanding had it that Pope Pius XII (in this movie played by John Gielgud), through his compromises, had made his church complicit with Holocaust evil. In defiance not only of the SS commander in Rome, Colonel Kappler (played by Christopher Plummer), but of the Pope (though not without the Pope’s knowledge), Monsignor O’Flaherty (Gregory Peck) quite astoundingly and heroically saved the lives of several thousand Jews and prisoners of war. The movie shows the activist priest not only in his incredibly risky rescue operations, but in his private devotions, visible images standing for the invisibles upon which he leaned in order to accomplish the extraordinary.

Two scenes in particular stood out for me: in one the Pope takes O’Flaherty through the Vatican’s “glories”, all the art and documents collected over 2000 years of history, now stored safe from bombs in an underground chamber behind steel doors. He makes plain his duty as he understands it is to preserve these treasures, the history, the art, and the continued existence of the church in its separate reality from the political. He warns O’Flaherty against giving the Nazi’s an excuse to invade the Vatican.

The other scene comes at the end, after liberation. The pope confesses to the priest he may have been wrong in valuing so highly the treasures stored in the bunker. “The real treasure of the church,” he says, “is that someone comes to it like you.” The relationship between pope and priest, both of them on the “good” side, each needing the other, fascinated me: without the protection of the Vatican the priest could not have saved lives; without the priest church would be about sanctimony rather than love.

That many liberals no longer can accept religious authority is understood. But by what authority then may we escape near total uniformity and conformity, completely disabling ourselves from the capacity to build the better world? It seems to me we must acknowledge uncomfortably the real existence of evil, beginning in oneself, that in turn leads one to the real existence of the Good, in the dimension opened through imagination.

The movie’s reconciliatory scene, between the authentic conservative and the courageous activist, helps me envision my work locally: that of keeping the nonprofit The Other Side – having the same spiritual point of origin as our late, mourned Cafe – as a protected space in Utica. Activism on the left, we’re given to understand, does not need religious sanctification. Perhaps. But it needs safe spaces, often those protected by churches. There is, in other words, a place for a quite fully conservative sense of purpose, protecting the invisibles, so relationship with the radically inclusive sense of the sacred can be preserved. Otherwise, how can activism lead to anything other than more traumatized souls?