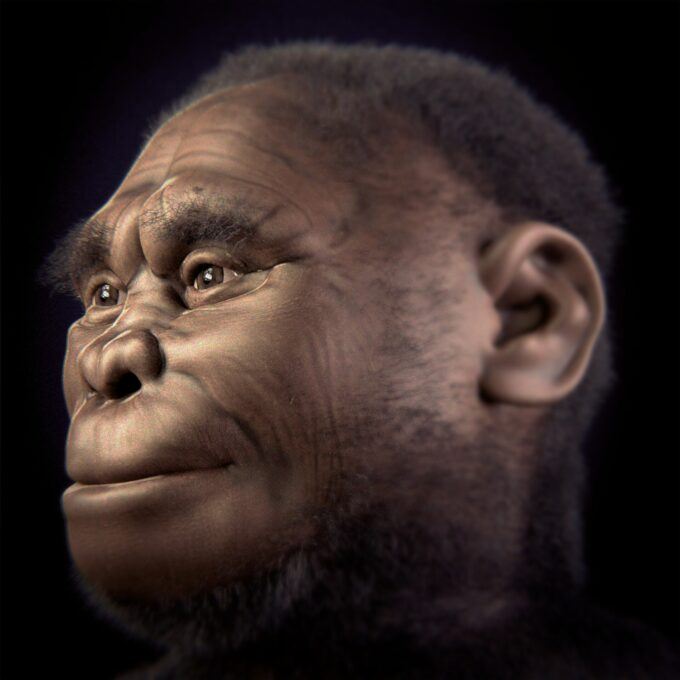

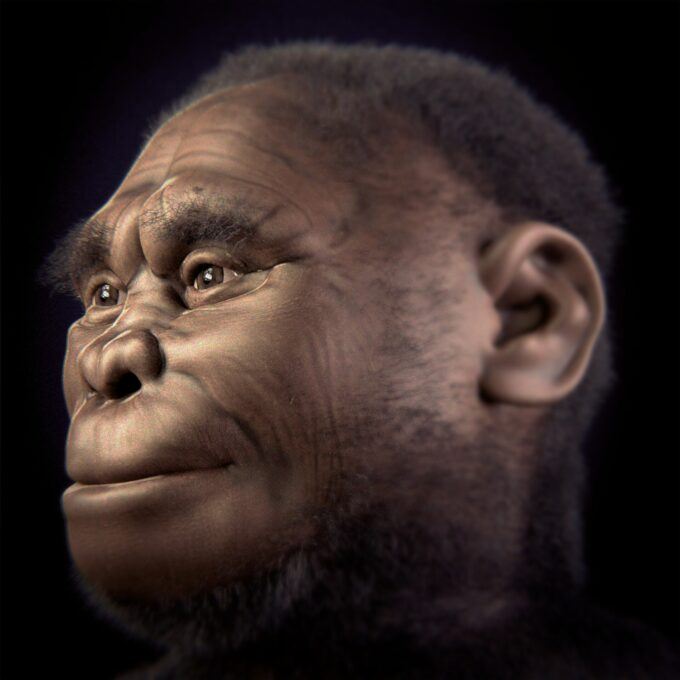

Archaeological Forensic Facial Reconstruction of the individual LB1 of the species Homo floresiensis. It has been released for the open source exhibition “Facce. I molti volti della storia umana“.

Until now, at least 14 different species have been assigned to the genus Homo since it emerged in Ethiopia some 2.8 million years ago revealing branching evolutionary stories of survival, intermixing, and extinctions. Archaeology is increasingly allowing us to glimpse into one of those epochs, from 50,000 to 35,000 years ago—the period of transition between the Middle and the Upper Paleolithic eras when modern humans emerged as the last representative of our genus on the planet.

In 2017, new finds from the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco were published, indicating that our species—H. sapiens—appeared on the scene as early as 300,000 years ago. Spreading into Eurasia l00,000 years later, these early anatomically modern humans rubbed shoulders with Neandertals and Denisovans, and may also have had encounters with five other distinct hominin populations that have only very recently been identified, including H. floresiensis, H. luzonensis, H. longi, and H. juluensis in Asia and Nesher Ramla Homo in the Levant.

Given what we know from historical events that chronicle human population exchanges through time, many archeologists question whether the “disappearances” of these other human lineages might have had anything to do with their coming into contact with modern humans.

Taking an example of human interactions that took place more than half a millennium ago helps us to understand how these interactions can deeply impact the human condition on multiple levels, many of which would be incomprehensible in the prehistoric archeological record without written documents.

The people of Western Europe living in hierarchized social configurations had reached a stage of technological readiness that led them to innovate ways to sustain life over extended periods of seafaring. As a result, they came into contact with the great civilizations established in the precolonial Americas over hundreds of generations. Before this encounter, the millions of people who lived in the Americas were oblivious to the existence of Europeans who would build powerful empires on the ruins of their treasured territorial and cultural heritage.

The consequences of the ensuing exchanges were both cataclysmic and transformative. Notwithstanding their immeasurable human impact, this contact altered the course of animal demography and deeply affected the global distribution of countless species of plants and trees that the colonizing populations freely displaced and exploited to enrich their own countries. Against the backdrop of this extraordinary scenario was the unprecedented spread of bacterial, viral, and fungal assemblages that indelibly modified evolutionary systems established over millennia—decimating an estimated 90 percent of Indigenous populations in their wake soon after the consolidation of colonization.

While it is difficult for us to conceive the magnitude of global turbulence generated after this event, we know that it led to a new world order that used human slavery to build systems of unidirectional wealth distribution whose ramifications still resound today.

Written records provide information about this period of global turmoil that help us to build our understanding of complex events that occurred in the past. Thirty thousand years from now, how will the multilevel repercussions of this period of human history be reflected in the archeological record?

Unlike the chaotic shifts that rocked the world at the cusp of the European Renaissance, archeologists studying the remote past cannot rely on written accounts of how ancient population interactions played out. In retrospect, it should be pointed out that the decimation of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas involved exchanges among a single human species, whereas the transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic involved human forms with distinct or even mosaic genetic, anatomic and sociocultural traits, with only one species remaining by around 35,000 years ago.

In conformity with the doctrines of their time, Europeans justified their actions by evoking cultural and racial differences that they believed made them superior to the populations they subjugated, while uneven levels of technological hegemony allowed them to consolidate domination.

Scientific results emanating from ancient genomics are shedding light on these paleo-interactions and painting a new picture of how humanity evolved, migrated, adapted, and reproduced during this key period of prehistory. Each individual’s genetic code is transcribed in the sequence of the base pairs composing the double-stranded helix of the DNA molecule carrying biological information passed on by reproduction. Discrete sections of a DNA strand are composed of the genes that define phenotypic (observable) and genotypic (hidden) traits defining a population. Throughout the world today, the human genetic code differs between individuals by only around 0.1 percent.

Under the right conditions, genetic data retrieved from ancient human fossils can be a powerful tool to study similarities and differences separating human lineages and is complementary to classical paleontological methods like Linnaean taxonomy and morphometric determination. Recent reconstructions of the genomic histories of fossil H. sapiens, Neandertals, and the Denisovans confirm not only that interspecific breeding took place but also that it produced fertile offspring, suggesting biological mixing played a role in the outcome of the modern human condition.

Having successfully occupied a huge territorial range stretching from the Levant to Western Europe and northward into Siberia for thousands of generations, our cousin species H. neanderthalensis is at the center of the enigma. The paleo-genetic data obtained from Neandertal fossils indicates a complex scenario with physical encounters taking place with modern humans between 65,000 and 47,000 years ago. Meanwhile, a Neandertal genetic inheritance of between 1 and 4 percent has been documented in present-day non-African populations, and gene flow from early modern humans to some Neandertalsalso took place as early as 100,000 years ago.

Analyzing genetic records from early modern humans living in Siberia and Central Europe 45,000-35,000 years ago revealed comparatively higher and relatively recent admixtures of Neandertal DNA, with these individuals believed to have contributed little to the gene pool of later European populations. In some cases, fossil human remains and their genomic signatures have even been found to display a mosaic of archaic and derived features, leading some paleoanthropologists to consider the possibility that Neandertals did not “disappear,” but rather, they were assimilated into a modern human clade developing in Eurasia at the time.

This raises the possibility of an ancestral population of anatomically modern humans that migrated out of Africa and subsequently underwent speciation as they spread into the ecologically diverse regions of Eurasia, where they evolved locally into diverse groups that occasionally interbred with one another, producing fertile offspring. From the Darwinian viewpoint, the decrease in Neandertal DNA genetic sequences shows that they were not selected in the natural evolutionary process that gave way to modern humans.

To explore this puzzling scenario, some archeologists turn to the cultural record left behind by these ancient human groups. Specific methods applied to study human-made artifacts are used to link them to predefined stages of techno-social evolution traditionally equated with distinct cultural complexes. Since the early 20th century, prehistorians have ascribed these cultural entities to different types of humans. But the apparent inter-specific mixing evidenced by the genetic data and the emergence of H. sapiens far earlier than previously thought have contributed to changing this traditional human-culture equation.

Once conveyed as brutish and primitive, Neandertals were alleged to have been incapable of matching the relatively “advanced” esthetic and technological capacities of their modern human counterparts. But this premise has also changed with new data demonstrating that Neandertals lived in socially advanced groups, that they appear to have practiced some form of art and body ornamentation, and that they intentionally buried their dead, suggesting powerful symbolic and even ritual practices.

So what do the artifacts tell us about the transitional period that saw the replacement of H. neanderthalensis by H. sapiens? A number of archeological sites preserve a record of this transitional phase, with Middle Paleolithic layers yielding the so-called Mousterian artifacts made from prepared stone cores attributed to Neandertals, overlain by strata containing Upper Paleolithic stone blades or bladelets attributed to H. sapiens. The blade industries attributed to modern humans are also associated with finely crafted bone, ivory, and antler artifacts, shell beads, ochre, and diverse forms of figurative art.

Using detailed technological and typological criteria, archeologists further subdivide these cultural complexes, refining the cultural groupings to reconstruct a chrono-cultural framework reflecting human population turnover in time and space. Because only one species of Homo lived during the Upper Paleolithic (after around 35,000 years ago), changes observed in the tool kits are thought to reflect different traditions, rather than different hominins. These shifts are attributed to multiple factors, including cultural transmission through inter-populational contact. However, since multiple species of Homo were present during the Middle Paleolithic, cultural change is often thought to signal the disappearance of one lineage and its replacement by another.

This begs the question: Do we observe a gradual or an abrupt transition from one phase to the next?

If modern humans and Neandertals were interbreeding, then we might assume that they could also have exchanged cultural and technological know-how. This means that we might anticipate finding some blending of cultural evidence, just as we might expect to find hominin fossils with intermediate anatomical traits.

Still, in most cases, the different cultural complexes defined for the Upper Paleolithic—generally beginning with the Early or Proto-Aurignacian cultures—appear sequentially above the Middle Paleolithic deposits, without intermixing of technological, typological, or stylistic features. Paradoxically, what we now know to have been a long period of contact between Neandertals and modern humans is not clearly reflected in the cultural materials found in the archeological record.

But there are some intriguing exceptions. In Western and Central Europe, the Near East, and Siberia, where these intra-specific exchanges are being validated by paleo-genomics and comparative anatomy in several archeological sites, the “intermediary” cultural scenarios are also becoming clearer. In some cases, transitional assemblages with elements inherited from the Middle Paleolithic combine with tools conveying innovative features commonly attributed to the Upper Paleolithic.

For now, there is little consensus about which hominin was responsible for making these “transitional” took kits in the timeframe that witnessed the disappearance or assimilation of the Neandertals and resulted in the ultimate domination of H. sapiens. Further research is needed to clarify humanity’s complex evolutionary history that—in the 3 million years since the emergence of Homo—has only been condensed into a single representative species since around 35,000 years ago.

When we compare this prehistoric chronicle to a transformative historical event for which we have a rich body of written information, we can see how huge revolutions can take place swiftly, almost imperceptibly, on the geological time scale. As archeologists discover more about the transitions in time that led us to where we are today, the subtleties of the complex biocultural mixing nascent to the contemporary globalization of our species are being revealed.

Deborah Barsky is a writing fellow for the Human Bridges, a researcher at the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution, and an associate professor at the Rovira i Virgili University in Tarragona, Spain, with the Open University of Catalonia (UOC). She is the author of Human Prehistory: Exploring the Past to Understand the Future (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

This article was produced by Human Bridges.