Small Town Politics Imbued with Arrested Development, Retrograde Thinking and a Whole Lotta MAGA

Not surprisingly, the recall is full of bullshit and lies, but one doozy is:

….In the last nine months, she has abused staff, gone on a radio show which attacked law enforcement and veterans, sued the city, filed ethics complaints against a meeting that she ran, and finally, not only called the sheriff’s office and Oregon Department of Environmental Quality on the city …

Shit dawg, my radio show, where in a brief sound bite, for a 60 minute venue, I disagreed lightly with Heidi about being respectful of men and women in blue and in camo. We did not talk about community policing, or policing watchdogs, or citizen oversight, or de-militarizing the cops, or forcing police to have trained crisis experts on the calls, and so much more.

I can go all ACAB crazy or call for defunding the police any fucking time. It had nothing to do with my guest or guests who may come onto the show, but leave it to the recall swindler to mention that. THAT. But I will do a show on this.

Key Books on the “Defund the Police” Movement

- Defund: Black Lives, Policing, and Safety for All by Sandy Hudson (2025): Examines the origins of police, argues that current safety models are based on sensationalism rather than data, and advocates for investing in community infrastructure.

- Defund the Police: An International Insurrection by Chris Cunneen et al. (2023): Provides a comprehensive overview of police divestment, using international case studies to explore alternatives to criminalization and imprisonment.

- Becoming Abolitionists: Essays on Police, Resistance, and the Future by Derecka Purnell (2021): A mix of memoir and analysis arguing that police cannot be reformed to eliminate racism and that resources should be shifted to social services.

- No More Police: A Case for Abolition by Mariame Kaba and Andrea Ritchie (2022): Offers a foundational argument for the complete abolition of policing.

- Defund the Police: 12 Questions and Answers by Peter Temes (2020): Explores the debate, arguing that while deep reform is necessary, total defunding may cause more harm than good, focusing on transitioning from a “warrior” to “guardian” model.

- Defund Fear: Safety Without Policing, Prisons, and Punishment by Zach Norris (2021): Focuses on creating a culture of care and community investment to produce genuine safety.

A New York City college professor who wrote about ending policing, was appointed by mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to work on community safety issues.

“I’m excited to announce that I have been asked to join the Mamdani Transition Team to work on community safety issues,” Alex Vitale wrote on the social media platform, X.

“A New Era for NYC.”

But Heidi and I also talked about her First Amendment rights to be on my show and other shows, and how the City Manager and the five council members have attacked her while she was on medical leave in an open city council meeting.

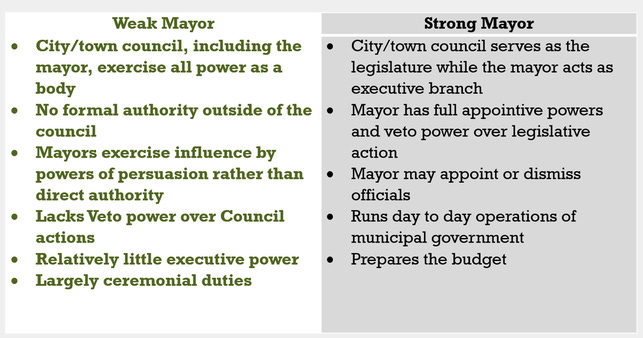

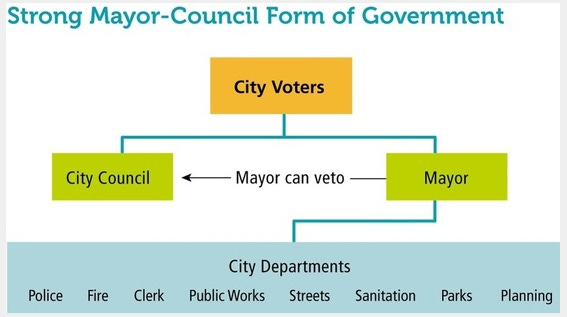

It seems like every city has a city manager who holds the real power and voters don’t get to decide on that person. What’s the point of having a mayor if you have a city manager anyway?

So, a small town needs a mayor running the council, with consensus, and a city manager, like the head planner, needs to listen to the mayor and council, not the other way around.

- The council-manager form gives too much power to one person – the city manager

- A professional manager, often chosen from outside the city, does not know the community and is too far from the voters

- Councils may leave too many decisions, making to the manager, who is not directly accountable to the public

- Without an elected chief executive, the community lacks political leadership

- The council-manager form is too much like a business corporation, which is not suitable for managing community needs

- City managers cost too much; local people could handle the job for less cost

- Citizens may be confused about who is in charge. Most expect the mayor to respond to their problems. The mayor has no direct control over the delivery of services and can only change policy through the city council

- City managers may leave a city when offered higher salaries and greater responsibilities in other cities

Here’s the Portland KOIN-TV news’ take a year ago:

After consulting their attorney in a closed executive session, Waldport City Council passed a resolution on Tuesday, reinstating Mayor Heide Lambert after she was expelled amid complaints that she created a hostile work environment.

The resolution comes after Mayor Lambert challenged the decision, leading Lincoln County Circuit Court Judge Sheryl Bachart to order the mayor’s reinstatement.

The mayor’s removal and reinstatement stem from letters sent by two City of Waldport employees on March 27, alerting City Council of “unacceptable and aggressive behavior” from the mayor two days earlier when the mayor visited City Hall to get her mail.

“Mayor Lambert was clutching a small stack of envelopes, demanding to know why the letters had not been scanned to her and council,” one employee wrote. “I greeted Mayor Lambert, asking how I might help. She, obviously frustrated and with an accusatory tone, commanded to know why the letter scans had not been sent to her, as they were addressed to her. I let her know that the letters had, in fact, been scanned and sent to (City Manager Dann Cutter) and that their delivery would come from either Dann or (another City Hall staffer). As that is their role.”

“She continued, in a confrontational manner, by insisting the letters be scanned to her and stated that ‘all these letters are complaints against Dann,’ as she clasped the letters, shaking them at us in emphasis. How she could possibly be aware of the contents of the letters without having read them is beyond me,” the letter continued.

“During a pause in her relentless onslaught, I let Mayor Lambert know that since none of our answers would satisfy her, we should end this conversation, and she should speak with Dann. She, of course, had the last word saying, ‘I won’t be speaking with Dann. I will be speaking with legal counsel,’” the letter claimed.

“I’m not easily intimidated,” the letter continues, “but Mayor Lambert’s behavior was not only out of line but was also in violation of city charter.”

In response to the complaints, the mayor sent a letter to City Council, explaining,

“I have read both letters and feel concerned that my statements and demeanor, though misinterpreted, might have contributed to feelings of unease, and I apologize for not realizing this at the time. While I want to be accountable for anything I may have said or done that caused either of these employees to feel ‘uncomfortable’ or ‘Intimidated,’ I am baffled by the allegations and do not believe I was ‘aggressive.’ Nor do I think I violated the city charter.”

Lambert explained that a community member had previously approached her at a supermarket and informed her that he submitted a complaint about Cutter. Before the City Hall incident, the mayor said she was advised to speak to City County Insurance Services — claiming she was advised by “CIS Attorney Ross (Davis)” to pick up her mail and ask the county clerk to scan the letters and send them to the council and the city attorney.

However, Davis claimed, “I have read Ms. Lambert’s 4/1 email. First, I am not an attorney and never claimed to be. Second, I did not advise her in anyway as she describes. She brought up the complaint and I advised to follow whatever City protocols there are for complaints against any employee by a citizen.”

In a unanimous vote on April 3, City Council expelled the mayor, citing a violation of the city charter, which states no member of the council shall directly or indirectly attempt to direct a city officer or employee in the performance of their duties.

One week later, the then-former mayor appeared at an April 10 City Council meeting where she was asked several times by council members to leave, but officials said she refused and hindered the meeting.

Members from the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Office attempted to remove Lambert peacefully, explaining the legal consequences. Officials said she continued to refuse.

Eventually, Lambert was escorted outside and cited for disorderly conduct before being released, where she was able to return to the meeting and sit in the public seating area. In a memo, Lincoln County District Attorney Jenna Wallace later announced she would not be pursuing charges against Lambert.

“We have never had an elected city official treat staff this way. What may seem like a minor incident is actually a serious legal concern,” Waldport City Council previously said. “Hostile work environment complaints lead to staff leaving positions, to costly lawsuits against the city, and to a near stop in city operations. In January, each of us, including Mayor Lambert, swore to uphold the Waldport City Charter and the Oregon and United States Constitutions. We take that pledge seriously.”

Lambert previously said this is a complicated situation, because community members had written formal complaints to her about the city manager that were labeled confidential.

“I went in to pick it up, and it had already been opened, and it had already been sent to the person that the complaints were about. And that was where I was confused,” she said. “So, I asked the city clerk to email the council those complaints, and I was told that was not what they were directed to do.”

Lambert hired a lawyer, previously telling KOIN 6 News that she had no interest in suing the city she was elected to lead but was prepared to take this issue to court if it’s not resolved.

“I’m fighting for my seat. I have to stick with my voters, and I have to keep running, keep fighting for my seat,” Lambert said. “I guess if it’s decided that I can be removed, then I’ll have to be reelected.”

‘Defeat for democracy’

In response to Mayor Lambert’s reinstatement, Waldport City Manager Dann Cutter raised concerns, telling KOIN 6 News this marks a “defeat for democracy.”

“The mayor is claiming this is a victory for democracy. Sadly, I think it’s the exact opposite. It showed that the threat of an expensive lawsuit can be used to silence elected officials from preventing abuse of power and corruption,” Cutter said.

The city manager then pointed to an ongoing lawsuit filed in 2023, which names Lambert. The lawsuit was filed by two staffers for the City of Yachats against the City — alleging they experienced discrimination and workplace harassment under several city managers, including Lambert, who was hired as the Yachats city manager in 2022. A spokesperson for the city told KOIN 6 News the city has no comment on the pending litigation.

“Two years ago, Ms. Lambert was named in a lawsuit with the city of Yachats, alleging discrimination and the creation of a hostile environment. Yachats is still fighting that lawsuit. Instead, the Waldport Council attempted to stand up for their staff when the same hostile environment was created here. Technicalities of the law were used to threaten the city with hundreds of thousands of taxpayers’ dollars to fight over what boils down to an unlawful direction of city staff by an elected official – the very definition of abuse of power. The Council absolutely acted in the city’s best interest then, and bravely, did the same last night – knowing that a small town cannot afford the fight, even when right. So, they put it back in the citizens hands to do the right thing,” Cutter furthered.

“The question is, will they? Will citizens stand up for the staff who work hard to build the city up? Or will they instead support a continuation of the behaviors for which their neighboring city is still paying. Because, after all is said and done, the Mayor never apologized to the employees,” Cutter said. “She claims she is supporting women’s rights – but they are women too who have been subject to harassment and ridicule for daring to stand up against those unlawful actions. Instead, the mayor wants to make this about the City Charter, attempting to hide behind technicalities of process.”

“So, no, this is a defeat for democracy and the protections against abuse by those in power – a theme we are seeing playing out nationally as well,” Cutter concluded.

*****

Lambert has lived in Waldport for 17 years, is raising three children, and she and her husband set down roots here. All are members of the community. She walked into a hornet’s nest of small-minded folk, a clique that is all about cronism and two staff making a mountain out of a molehill. The City MANAGER has too much power, and he was once the Mayor of Waldport. These people have to move on, gotta go.

Lambert was voted in as the Mayor, two year term, and that ends Jan. 2027. The recall is insane, having to gather 200 signatures, and then put into a special ballot for voters to vote on. We are talking May or June. If she loses, then one of the councilmembers, another City Manager bootlicker, gets the role of leading the council.

I asked Lambert to read this statement she made which was published in something called the Free Press. Follow along by listening to the entire interview above.

Hanging on by a Thread of Hope

By Heide Lambert, Mayor of Waldport, Oregon

In a small coastal town of 2,000 people, you wouldn’t expect to see the forces tearing apart our democracy so clearly. And yet, Waldport, Oregon, has become a case study in how power, fear, and disinformation corrode civic life—at the local level and far beyond.

Since being elected to a two-year volunteer term as mayor, our town has made national news more than once. First, when the city manager and council unconstitutionally expelled me less than three months into my term. Then, when residents united to stop ICE from housing agents in a rundown hotel. Most recently, we mourned the loss of County Commissioner Claire Hall, whose body succumbed after enduring relentless bullying tied to a recall effort.

I write because the misdirected hate in my county mirrors a much larger crisis—and it has shaken my faith in the systems meant to protect us.

Since becoming an elected official, I have encountered hostility I never imagined would accompany public service. A smear campaign, driven by city leadership, made me question whether running for office was worth the cost. What I have learned is this: it doesn’t take a mob to undermine democracy. It takes a few people with power and no accountability.

As I watch national news of war initiated by the directive of a single man, I recognize the same pattern playing out locally and across the country. Corruption is no longer treated as a crime. Norms once considered foundational—truth, restraint, decency—are dismissed as inconveniences. This is not what freedom looks like, nor what our Constitution was written to allow.

Because I was not the mayor city staff and council wanted, my leadership has faced ongoing resistance. For over a year, they have refused to recognize my role and have used their authority to undermine my credibility, promoting narratives presented as truth regardless of fact.

The democracy I was raised to believe in depended on checks and balances, due process, and ethical leadership. Those values feel eroded. The worst behavior is no longer condemned—it is rewarded. We openly shame one another over politics, religion, race, gender, and sexuality, while the influence of money tightens its grip from the smallest towns to the highest offices.

I never expected this level of scrutiny for volunteering to serve my community. I ran to contribute years of experience managing complex projects with limited resources and collaborating across differences. I currently work with specialists in trauma and neurobiology, helping train justice system professionals across Oregon to recognize trauma so they do not cause further harm. The irony is painful: my civic role has placed me in a constant state of being targeted.

I use every coping skill I have ever taught to stay steady while city leadership uses my existence as a distraction from their own misconduct. Appeals for oversight have gone nowhere. Those with authority prefer the status quo—and in doing so, allow harm to continue.

I once believed my candidacy could show others that anyone could step into leadership. Now I am less certain. Fear of losing power and money has silenced residents and intimidated those who ask questions. We live in a media desert, without local journalism to verify facts, leaving social media distortions to fill the void.

Each month I wait for clarity, yet things continue to worsen. It feels like a witch hunt, as my brown, queer, and trans community lives in fear. The strain of never knowing if you are safe seeps into bodies, minds, and relationships. Sitting with loved ones in that space takes quiet strength.

I was elected not because I sought power, but because a majority of voters asked me to serve. Although a recall effort is underway, I refuse to let a small, disgruntled group dictate how I show up. I will continue to serve with integrity, transparency, and a commitment to the whole community.

Democracy does not collapse all at once. It erodes through silence, intimidation, and our willingness to accept what we know is wrong. We are being harmed together—and only together will we overcome it.

We are all hanging on by a thread of hope. And the more we keep showing up for one another, the stronger that thread becomes.

*****

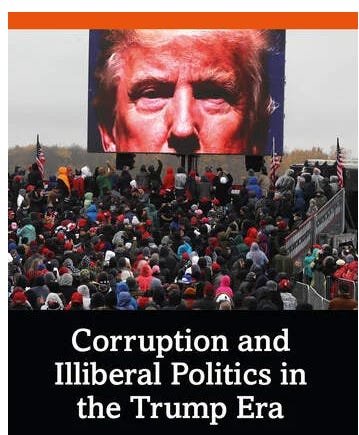

MAGA is infecting EVERYTHING, and the leeches and rabid racists and conservative retrogrades are coming out of the woodwork and out from under their rocks:

In “Chaos Comes Calling: The Battle Against the Far-Right Takeover of Small-Town America,” journalist Sasha Abramsky documents how two rural communities in the Pacific Northwest were overwhelmed by far-right radicals. It’s a sobering story, but also one that offers hope. Concerned citizens in Clallam County, Washington, beat back the MAGA menace, offering a model for others looking to protect their communities, whether their immediate town or the nation. Abramsky spoke with Salon about his work and why it matters for the future.

*****

Lambert and I talked about a small town that needs roads fixed, better economic development, more mitigation around extreme flooding and king tides, better recruitment of businesses and business partners, and just bringing down the costs of flushing your toilet and turning on the lights.

Pragmatism used to define local politics: getting roads built, filling in potholes, making sure kids had safe spaces on the way to school. All of that local pragmatic politics got swamped by the sheer rage of the national discourse. But it goes the other way, too. The more local politics came to be defined by these increasingly angry battles, the more it played into a national narrative. A local story would be picked up by someone like Tucker Carlson, who would use it to whip up rage. Not just nationally, but because of social media, it would be picked up internationally.