Trump joins the global Jewish conspiracy

(official White House photo)

(official White House photo)

March 09, 2026

COMMON DREAMS

It bears repeating that Donald Trump’s rationale for war against Iran keeps shifting because Trump himself does not believe his own rationales. The goal of this war has little to do with Iran. It has to do with creating conditions in which an old, depleted and unpopular president looks big, tough and loved on American TV.

But there may be a reason outside the president’s fear of defeat in this year’s congressional elections. While he believes that he benefits from the perception of being a war president, it looks like the decision to become one wasn’t entirely his to make.

Early reporting on the war suggested that Israel was going to attack Iran without or without Trump, and that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was lobbying him to join the effort. USA Today reported yesterday that Netanyahu decided in November of last year to order a long-planned operation to assassinate Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Marco Rubio confirmed that reporting on Monday: "We knew that there was going to be an Israeli action. We knew that that would precipitate an attack against American forces, and we knew that if we didn't preemptively go after them before they launched those attacks, we would suffer higher casualties.”

Just so I have this straight in my mind: Trump did not attack Iran in order to stop it from having nukes; in order to stop it from being a global leader in state-sponsored terrorism; in order to liberate the Iranian people; or in order to manifest world peace.

No, the president launched an illegal and unjustified war with Iran because America’s ally, Israel, put him in a no-win situation in which, as one source told the Post over the weekend, “the only debate that seemed to be remaining was whether the US would launch in concert with Israel or if the US would wait until Iran retaliated on US military targets in the region and then engage.”

Trump could have condemned Netanyahu after the fact, but apparently the appeal of being a war president was too great.

If I were the commander-in-chief of the world’s mightiest military, and if I allowed a foreign head of state to lead me around by the nose, I would also come up with a couple dozen reasons for going to war with Iran, no matter how unconvincing those reasons may be, because I would be highly motivated to draw attention away from the view that I’m not entirely in charge.

I mean, Trump can’t even take credit for Khamenei’s death. Pete Hegseth told reporters the Israeli strikes killed him Saturday. The only “credit” he can claim is having followed Netanyahu’s lead.

That it appears the decision to attack Iran was Netanyahu’s more than it was Trump’s is going to be a problem, most immediately because of the outcry in the Congress. If Trump was not acting in self-defense, and clearly he was not, then this war against Iran is a war of choice, which requires the consent of the Congress. Trump is going to be forced to explain himself, thus risking being held accountable for the spike in goods and oil prices, Tuesday’s sell-off on Wall Street and general chaos in the Middle East.

(According to journalist Steve Herman, the State Department told Americans to “immediately leave 16 countries and territories: Bahrain, Egypt, Gaza, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, UAE, West Bank and Yemen.” NBC News reported that the mandatory orders are coming despite many airports in the region being shuttered. In Qatar, Americans who can’t get out were advised that “should not rely on the US government for assisted departure or evacuation.”)

The White House’s best rationale for war seems to be that the US was forced to attack Iran, because Iran was forced to defend itself against Israel’s attack. Such a rationale is not going to fly with most of the Congress, including many maga Republicans. That’s why Trump lied Tuesday. He said Netanyahu didn’t force my hand. I forced his. According to Kaitlan Collins, he said “it was his opinion that Iran was going to attack first if the US didn't.”

For the lie to work, however, he needs the full faith of maga. He needs the base to trust him enough to play along. To do that, he must affirm his dominance. If supporters believe he’s Netanyahu’s puppet, however, such displays of dominance will seem empty and hollow to his own people, thus creating problems much bigger than abstract debates in the Congress over war powers.

To understand the problem he has created for himself, bear in mind the true nature of America First, which has been largely sanitized by the Washington press corps. It is not rooted in high-minded principles like freedom and national sovereignty. It is rooted in conspiracy theory and antisemitism, which are often provided a veneer of respectability by rightwing intellectuals and gullible reporters. Peel away the noble-sounding language, however, about nation-builders “intervening in complex societies that they did not even understand themselves,” as Trump said last year, and what you find at the center of America First is an unshakeable belief in a global Jewish conspiracy against America.

This belief in a global Jewish conspiracy against America was the foundation beneath the push to release the Epstein files during Trump’s 2024 campaign. The belief took on a slightly different form, but the animus was the same. Trump was supposed to have been the hero sent by God to fulfill a prophecy to save America from a secret cabal of powerful Jews who sex-trafficked young girls to untouchable elites. In maga lore, Jeffrey Epstein came to represent this shadowy, malevolent syndicate. Once reelected, Trump was supposed to bring them all to justice. When he didn’t, he triggered a crisis of faith that can be registered in recent polling that lumps him in with the rest of the “wealthy elites” who act with impunity for the law – the so-called “Epstein class.”

The Times reported Tuesday on the growing uproar within the maga movement over the possibility that Netanyahu said “jump” and Trump asked “how high?” Some of the most invested maga personalities, men like Jack Posobiec, told the Times that divisions can be overcome and lingering doubts will only be relevant to future candidates to lead the maga movement.

If supporters believed Trump betrayed principles, Posobiec might be right, as they don’t really care about principles. Supporters could shift from anti-war to pro-war as seamlessly as Trump does. But what Posobiec is ignoring, because it’s in his interest to ignore it, is that America First is not rooted in high-minded principles. It’s rooted in Jew-hate. Supporters are not going to warm up to the appearance of an American president seeming to take orders from the leader of a Jewish state. Instead, they might see Trump doing to believers in America First what he has done to supporters who demanded the release of the Epstein files.

Again, this is why the president lied Tuesday. In an attempt to assert dominance, he said he was the one to force Netanyahu’s hand, not the other way around. That might have worked – the base might have trusted him enough to play along with the lie – but for his already established betrayal in the Epstein case. With Iran, he has now compounded maga’s crisis of faith. He must contend with the growing suspicion that instead of destroying the global Jewish conspiracy against America, he has joined it.

It bears repeating that Donald Trump’s rationale for war against Iran keeps shifting because Trump himself does not believe his own rationales. The goal of this war has little to do with Iran. It has to do with creating conditions in which an old, depleted and unpopular president looks big, tough and loved on American TV.

But there may be a reason outside the president’s fear of defeat in this year’s congressional elections. While he believes that he benefits from the perception of being a war president, it looks like the decision to become one wasn’t entirely his to make.

Early reporting on the war suggested that Israel was going to attack Iran without or without Trump, and that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was lobbying him to join the effort. USA Today reported yesterday that Netanyahu decided in November of last year to order a long-planned operation to assassinate Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Marco Rubio confirmed that reporting on Monday: "We knew that there was going to be an Israeli action. We knew that that would precipitate an attack against American forces, and we knew that if we didn't preemptively go after them before they launched those attacks, we would suffer higher casualties.”

Just so I have this straight in my mind: Trump did not attack Iran in order to stop it from having nukes; in order to stop it from being a global leader in state-sponsored terrorism; in order to liberate the Iranian people; or in order to manifest world peace.

No, the president launched an illegal and unjustified war with Iran because America’s ally, Israel, put him in a no-win situation in which, as one source told the Post over the weekend, “the only debate that seemed to be remaining was whether the US would launch in concert with Israel or if the US would wait until Iran retaliated on US military targets in the region and then engage.”

Trump could have condemned Netanyahu after the fact, but apparently the appeal of being a war president was too great.

If I were the commander-in-chief of the world’s mightiest military, and if I allowed a foreign head of state to lead me around by the nose, I would also come up with a couple dozen reasons for going to war with Iran, no matter how unconvincing those reasons may be, because I would be highly motivated to draw attention away from the view that I’m not entirely in charge.

I mean, Trump can’t even take credit for Khamenei’s death. Pete Hegseth told reporters the Israeli strikes killed him Saturday. The only “credit” he can claim is having followed Netanyahu’s lead.

That it appears the decision to attack Iran was Netanyahu’s more than it was Trump’s is going to be a problem, most immediately because of the outcry in the Congress. If Trump was not acting in self-defense, and clearly he was not, then this war against Iran is a war of choice, which requires the consent of the Congress. Trump is going to be forced to explain himself, thus risking being held accountable for the spike in goods and oil prices, Tuesday’s sell-off on Wall Street and general chaos in the Middle East.

(According to journalist Steve Herman, the State Department told Americans to “immediately leave 16 countries and territories: Bahrain, Egypt, Gaza, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, UAE, West Bank and Yemen.” NBC News reported that the mandatory orders are coming despite many airports in the region being shuttered. In Qatar, Americans who can’t get out were advised that “should not rely on the US government for assisted departure or evacuation.”)

The White House’s best rationale for war seems to be that the US was forced to attack Iran, because Iran was forced to defend itself against Israel’s attack. Such a rationale is not going to fly with most of the Congress, including many maga Republicans. That’s why Trump lied Tuesday. He said Netanyahu didn’t force my hand. I forced his. According to Kaitlan Collins, he said “it was his opinion that Iran was going to attack first if the US didn't.”

For the lie to work, however, he needs the full faith of maga. He needs the base to trust him enough to play along. To do that, he must affirm his dominance. If supporters believe he’s Netanyahu’s puppet, however, such displays of dominance will seem empty and hollow to his own people, thus creating problems much bigger than abstract debates in the Congress over war powers.

To understand the problem he has created for himself, bear in mind the true nature of America First, which has been largely sanitized by the Washington press corps. It is not rooted in high-minded principles like freedom and national sovereignty. It is rooted in conspiracy theory and antisemitism, which are often provided a veneer of respectability by rightwing intellectuals and gullible reporters. Peel away the noble-sounding language, however, about nation-builders “intervening in complex societies that they did not even understand themselves,” as Trump said last year, and what you find at the center of America First is an unshakeable belief in a global Jewish conspiracy against America.

This belief in a global Jewish conspiracy against America was the foundation beneath the push to release the Epstein files during Trump’s 2024 campaign. The belief took on a slightly different form, but the animus was the same. Trump was supposed to have been the hero sent by God to fulfill a prophecy to save America from a secret cabal of powerful Jews who sex-trafficked young girls to untouchable elites. In maga lore, Jeffrey Epstein came to represent this shadowy, malevolent syndicate. Once reelected, Trump was supposed to bring them all to justice. When he didn’t, he triggered a crisis of faith that can be registered in recent polling that lumps him in with the rest of the “wealthy elites” who act with impunity for the law – the so-called “Epstein class.”

The Times reported Tuesday on the growing uproar within the maga movement over the possibility that Netanyahu said “jump” and Trump asked “how high?” Some of the most invested maga personalities, men like Jack Posobiec, told the Times that divisions can be overcome and lingering doubts will only be relevant to future candidates to lead the maga movement.

If supporters believed Trump betrayed principles, Posobiec might be right, as they don’t really care about principles. Supporters could shift from anti-war to pro-war as seamlessly as Trump does. But what Posobiec is ignoring, because it’s in his interest to ignore it, is that America First is not rooted in high-minded principles. It’s rooted in Jew-hate. Supporters are not going to warm up to the appearance of an American president seeming to take orders from the leader of a Jewish state. Instead, they might see Trump doing to believers in America First what he has done to supporters who demanded the release of the Epstein files.

Again, this is why the president lied Tuesday. In an attempt to assert dominance, he said he was the one to force Netanyahu’s hand, not the other way around. That might have worked – the base might have trusted him enough to play along with the lie – but for his already established betrayal in the Epstein case. With Iran, he has now compounded maga’s crisis of faith. He must contend with the growing suspicion that instead of destroying the global Jewish conspiracy against America, he has joined it.

'Clearly there’s a coverup': Evidence mounts against Epstein’s suicide

Ghislaine Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein are seen in this image released by the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C., U.S., on December 19, 2025. (U.S. Justice Department/Handout)

March 09, 2026

ALTERNET

No matter how many times President Donald Trump “starts illegal wars and engages in military strikes, it will never be enough to make people forget that he was best friends with the world’s most notorious pedophile, Jeffrey Epstein,” argued Left Hook publisher Wajahat Ali.

Ali joined forces with television producer and Epstein documentary creator Zev Shalev and Blue Amp Media editor Ellie Leonard as they discussed new information posted in the Miami Herald incriminating prison guards in covering up the alleged murder of convicted sex-trafficker Jeffrey Epstein. Both the New York Medical Examiner and the U.S. Department of Justice concluded that Epstein died by suicide, but a forensic pathologist hired by Epstein’s estate to attend the autopsy, has said he Epstein’s injuries look more similar to strangulation than suicide.

However, new information from the Herald by Epstein researcher Julie K. Brown suggests prison guards discussed covering up Epstein’s death, according to FBI conversation with a fellow inmate.

“An inmate housed at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York told the FBI he overheard guards talking about covering up Jeffrey Epstein’s death on the morning he died,” reports the Herald. “The federal government’s online Epstein library contains a five-page handwritten report of an FBI interview with an inmate who awoke the morning of Aug. 10, 2019 to the loud commotion in the Special Housing Unit, or SHU, where he and Epstein were jailed.”

“… [C]learly there's a cover up. Clearly the DOJ has been covering up for the president of the United States,” said Shalev. “That is a scandal of huge, mammoth proportions. … We can't have that. We can't have a president of the United States facing allegations, multiple allegations of raping young girls and then still being a sitting president as the DOJ covers up for him. I mean, it's just unacceptable. It's untenable for any regime.”

Shalev told Ali that the circumstances under which Epstein died had far too many holes not to draw suspicion.

“How did [the guard Tova Noel] have time … to do all these searches, but then didn't have time to do the regular 30-minute checks on the prisoner that she was meant to do because she had fallen asleep? I mean, one of these things doesn't add up. Either the guards fell asleep or they were so distracted doing searches, but their job is to do regular check-ins on the prisoner, and they didn't do that. For… a whole night.”

“And then she gets this mysterious $5,000 check or whatever it is — payment that she gets. No one knows where she's from. She's just a prison guard.

The Herald reported a five-page handwritten report in the federal government’s online Epstein library, consisting of an FBI interview with an inmate who awoke the morning of Aug. 10, 2019 to a loud commotion in the Special Housing Unit where he and Epstein were held.

“Breathe! Breathe!” he recalled officers shouting about 6:30 a.m., according to the Herald, followed by an officer saying: “Dudes, you killed that dude.”

The inmate then heard a female guard reply “If he is dead, we’re going to cover it up and he’s going to have an alibi -- my officers,” according to the FBI notes. The inmate claimed the whole wing overheard the exchange.

Later, after learning Epstein had died, inmate claimed other inmates said “Miss Noel killed Jeffrey.”

“It's not common for her to get these $5,000 infusions of cash. And obviously the whole thing stinks,” said Shalev. “I mean, with the circumstantial evidence it’s hard to see how he committed suicide there. It's hard to see.”

No matter how many times President Donald Trump “starts illegal wars and engages in military strikes, it will never be enough to make people forget that he was best friends with the world’s most notorious pedophile, Jeffrey Epstein,” argued Left Hook publisher Wajahat Ali.

Ali joined forces with television producer and Epstein documentary creator Zev Shalev and Blue Amp Media editor Ellie Leonard as they discussed new information posted in the Miami Herald incriminating prison guards in covering up the alleged murder of convicted sex-trafficker Jeffrey Epstein. Both the New York Medical Examiner and the U.S. Department of Justice concluded that Epstein died by suicide, but a forensic pathologist hired by Epstein’s estate to attend the autopsy, has said he Epstein’s injuries look more similar to strangulation than suicide.

However, new information from the Herald by Epstein researcher Julie K. Brown suggests prison guards discussed covering up Epstein’s death, according to FBI conversation with a fellow inmate.

“An inmate housed at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York told the FBI he overheard guards talking about covering up Jeffrey Epstein’s death on the morning he died,” reports the Herald. “The federal government’s online Epstein library contains a five-page handwritten report of an FBI interview with an inmate who awoke the morning of Aug. 10, 2019 to the loud commotion in the Special Housing Unit, or SHU, where he and Epstein were jailed.”

“… [C]learly there's a cover up. Clearly the DOJ has been covering up for the president of the United States,” said Shalev. “That is a scandal of huge, mammoth proportions. … We can't have that. We can't have a president of the United States facing allegations, multiple allegations of raping young girls and then still being a sitting president as the DOJ covers up for him. I mean, it's just unacceptable. It's untenable for any regime.”

Shalev told Ali that the circumstances under which Epstein died had far too many holes not to draw suspicion.

“How did [the guard Tova Noel] have time … to do all these searches, but then didn't have time to do the regular 30-minute checks on the prisoner that she was meant to do because she had fallen asleep? I mean, one of these things doesn't add up. Either the guards fell asleep or they were so distracted doing searches, but their job is to do regular check-ins on the prisoner, and they didn't do that. For… a whole night.”

“And then she gets this mysterious $5,000 check or whatever it is — payment that she gets. No one knows where she's from. She's just a prison guard.

The Herald reported a five-page handwritten report in the federal government’s online Epstein library, consisting of an FBI interview with an inmate who awoke the morning of Aug. 10, 2019 to a loud commotion in the Special Housing Unit where he and Epstein were held.

“Breathe! Breathe!” he recalled officers shouting about 6:30 a.m., according to the Herald, followed by an officer saying: “Dudes, you killed that dude.”

The inmate then heard a female guard reply “If he is dead, we’re going to cover it up and he’s going to have an alibi -- my officers,” according to the FBI notes. The inmate claimed the whole wing overheard the exchange.

Later, after learning Epstein had died, inmate claimed other inmates said “Miss Noel killed Jeffrey.”

“It's not common for her to get these $5,000 infusions of cash. And obviously the whole thing stinks,” said Shalev. “I mean, with the circumstantial evidence it’s hard to see how he committed suicide there. It's hard to see.”

Bombshell investigation verifies key details in 13-year-old Trump accuser's story

Alexander Willis

March 9, 2026

Donald Trump holds a cabinet meeting at the White House in Washington. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

Key details in the account of a woman who’s accused President Donald Trump of sexually assaulting her when she was a minor were verified Sunday in an explosive investigation conducted by The Post and Courier.

The woman first came forward to the FBI following the 2019 arrest of Jeffrey Epstein, and was interviewed by the agency four separate times. A Justice Department source told the Miami Herald that the woman was found credible by the agency, the outlet reported.

In her interviews with the FBI, the woman accused Epstein and at least two other associates, including Trump, of sexual assault when she was 13. She accused Trump of sexually assaulting her, pulling her hair and punching her in the head sometime in the mid-1980s.

While details of her specific allegations against Trump were not further verified by The Post and Courier, other details she provided the FBI were, giving further credence to her account.

Details verified by The Post and Courier include the fact that her mother had rented a home to Epstein in South Carolina. The outlet also verified details of another associate of Epstein’s that she accused of sexually assaulting her, an Ohio businessman that she said was "affiliated with a Cincinnati-based college,” and whom the outlet confirmed was a member of a for-profit school.

The woman also accused Epstein of possessing nude photographs of her as a minor and extorting her mother for money to keep them secret, which she said led her mother to begin stealing money. The Post and Courier confirmed that the mother had been charged with stealing $22,000 from the real estate firm she worked for.

The woman’s identity was verified by The Post and Courier by cross referencing details of her account with various public records and old news clippings, though the outlet declined to name her, and both she and her attorney declined to comment on the report.

Due to the sheer volume of Epstein-related materials released by the DOJ, many of the documents contain unverified, uncorroborated allegations that do not constitute evidence, and do not establish wrongdoing. Trump is not facing any criminal charges or investigations related to the allegation.

Alexander Willis

March 9, 2026

Donald Trump holds a cabinet meeting at the White House in Washington. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

Key details in the account of a woman who’s accused President Donald Trump of sexually assaulting her when she was a minor were verified Sunday in an explosive investigation conducted by The Post and Courier.

The woman first came forward to the FBI following the 2019 arrest of Jeffrey Epstein, and was interviewed by the agency four separate times. A Justice Department source told the Miami Herald that the woman was found credible by the agency, the outlet reported.

In her interviews with the FBI, the woman accused Epstein and at least two other associates, including Trump, of sexual assault when she was 13. She accused Trump of sexually assaulting her, pulling her hair and punching her in the head sometime in the mid-1980s.

While details of her specific allegations against Trump were not further verified by The Post and Courier, other details she provided the FBI were, giving further credence to her account.

Details verified by The Post and Courier include the fact that her mother had rented a home to Epstein in South Carolina. The outlet also verified details of another associate of Epstein’s that she accused of sexually assaulting her, an Ohio businessman that she said was "affiliated with a Cincinnati-based college,” and whom the outlet confirmed was a member of a for-profit school.

The woman also accused Epstein of possessing nude photographs of her as a minor and extorting her mother for money to keep them secret, which she said led her mother to begin stealing money. The Post and Courier confirmed that the mother had been charged with stealing $22,000 from the real estate firm she worked for.

The woman’s identity was verified by The Post and Courier by cross referencing details of her account with various public records and old news clippings, though the outlet declined to name her, and both she and her attorney declined to comment on the report.

Due to the sheer volume of Epstein-related materials released by the DOJ, many of the documents contain unverified, uncorroborated allegations that do not constitute evidence, and do not establish wrongdoing. Trump is not facing any criminal charges or investigations related to the allegation.

7 March, 2026

Left Foot Forward

If Epstein’s networks helped broker access or funding for political movements, it’s a matter of public concern. These aren’t insinuations, but a matter of accountability, and in the unresolved story of Brexit, accountability remains in short supply.

When the latest tranche of documents linked to Jeffrey Epstein was released earlier this year, much of the British reaction focused on familiar establishment names, notably Peter Mandelson and former Prince Andrew. Given the seriousness of the allegations surrounding them, that scrutiny is understandable.

But the spotlight has been too narrow.

Buried within the correspondence and contact lists are connections that reach into Britain’s hard-right networks and intersect with the political forces that drove Brexit. Yet, these connections have largely been overlooked or ignored by mainstream media.

Epstein was not merely a disgraced financier cultivating proximity to power, he was enthusiastic about Britain’s departure from the EU and celebrated the nationalist turn in Western politics.

Inclusion in Epstein’s files does not, in itself, imply wrongdoing. Yet the context of those mentions, the political projects being discussed, the money being courted, and the alliances being enriched, is a matter of public interest.

If the disclosures are to mean anything beyond lurid scandal, they must prompt a broader examination of how wealth, influence and political power intervene in modern Britain.

Brexit as “just the beginning”

Among the material are emails in which Epstein discusses Brexit with tech billionaire Peter Thiel. In one exchange, Epstein describes Britain’s vote to leave the European Union as “just the beginning,” heralding a “return to tribalism,” a “counter to globalisation,” and the forging of “amazing new alliances.”

Such remarks suggest that Brexit was viewed in certain elite circles not merely as a domestic democratic event, but as part of a broader ideological realignment across the West.

Thiel’s footprint in the UK has grown steadily in recent years. As Left Foot Forwardreported in 2022, his data analytics firm Palantir Technologies secured multiple UK government contracts during the pandemic and has undertaken extensive work with the Ministry of Defence, including a £10 million contract in March 2022 for data integration and management.

A report by Byline Times described a “Thiel network” seeking to influence debates around free speech in academia, and part of a broader effort to normalise anti-liberal ideas among British intellectuals and policymakers.

Some figures linked to these debates, including right-wing commentator Douglas Murray and a British Anglican priest and life peer Nigel Biggar, who regularly rages against ‘woke’ culture, have also been associated with initiatives such as the Free Speech Union, founded by perennial culture warrior, Toby Young.

Thiel’s influence also extends through his Thiel Fellowship programme, which has backed entrepreneurs including Christian Owens, founder of the UK payments “unicorn” Paddle.

None of this proves a coordinated “Thiel–Epstein Brexit plot,” but it does point to something subtler, and arguably more consequential. As the New World observed in an analysis about the Epstein files and the Brexit connection, “while millions voted Leave to strike back at a remote elite, parts of that same elite were calmly gaming out how the resulting disorder might be useful to them.”

That tension alone warrants scrutiny.

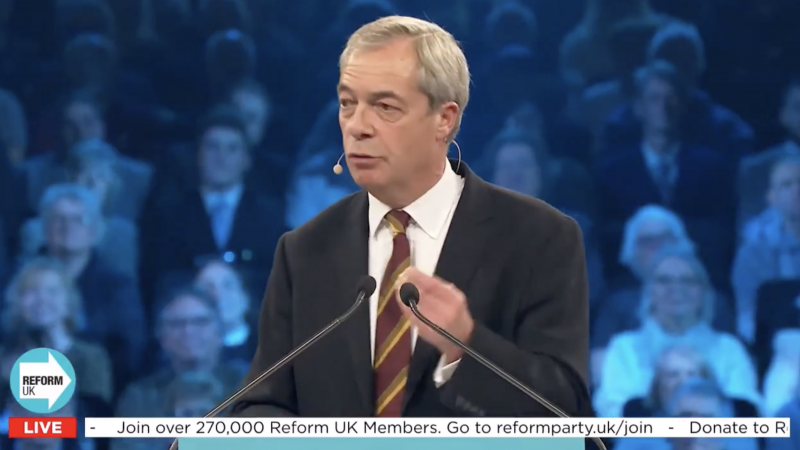

Nigel Farage and Steve Bannon

The Reform UK leader appears dozens of times in the Epstein files, though many references reportedly stem from duplicated email chains or attached news articles. Farage has denied ever meeting or speaking with Epstein.

Yet the context in which his name arises is important.

Steve Bannon, a former White House chief strategist to Donald Trump, described brilliantly by the New World’s Steve Anglesey as “the sweaty MAGA insider/outsider who once fancied himself a Brexit architect and dreamed of setting up a pan-European far right movement that would ultimately destroy the EU,” appears in thousands of exchanges with Epstein. In one message, Bannon boasts about his relationship with Farage. In another, he writes: “I’ve gotten pulled into the Brexit thing this morning with Nigel, Boris and Rees Mogg.”

The correspondence shows Bannon attempting to tap Epstein for support and funding to bolster far-right movements in Europe. He discussed raising money for figures such as Italy’s deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini and France’s Marine Le Pen, showing the transnational nature of these networks.

Again, mention does not equal misconduct, but when a financier later exposed as a serial abuser is simultaneously being courted as a potential backer of nationalist political movements, the public is entitled to ask questions about access, influence and intent.

Tommy Robinson and the “backbone of England”

The files also contain references to UK far-right activist, Tommy Robinson.

Bannon has never shied away from sharing his support for Robinson. At the 2024 Conservative Political Action Conference, when on stage with Liz Truss, he described the founder of the English Defence League as a “hero” and Truss appeared to agree with him. “That is correct,” she said.

When Robinson was released from prison in 2018, Epstein messaged Bannon: “Tommy Robinson. !! good work.” Bannon responded: “Thanks.”

In July 2019, after Epstein shared an article reporting Robinson’s contempt of court conviction for live-streaming defendants in a child sexual exploitation trial, Bannon replied by calling Robinson the “backbone of England.”

The significance here is not that Robinson appears in correspondence, but that discussions around him sit within a wider ecosystem, that is wealthy financiers, American political strategists and European nationalist figures exchanging messages about funding, media and mobilisation.

Nick Candy, Reform UK and transatlantic links

Nick Candy, luxury property mogul and now treasurer of Reform UK, is also mentioned numerous times in the files, in discussions that appear to concern the potential sale of Epstein’s New York mansion.

In 2024, Candy left the Conservative Party to join Reform. He later attended a strategy meeting at Trump’s Florida residence alongside Farage and tech billionaire Elon Musk. All three men appear within the tranche of documents released by the Department of Justice.

Some messages reference Candy in connection with Ghislaine Maxwell, though the full context of those exchanges remain partially redacted – we’ll come on to redaction shortly.

The files also reveal previously underreported contact between Musk and Epstein in 2012 and 2013, including discussions about a possible visit to Epstein’s private island. The visit does not appear to have taken place.

Like Bannon, Musk has actively involved himself in European politics. He has repeatedly got into spats with politicians including Keir Starmer.

“Civil war is inevitable” … “Britain is going full Stalin”… “The people of Britain have had enough of a tyrannical police state,” are just some of his comments on X in recent years.

And he’s used his own platform X to amplify voices on the right and far-right online, including sending a heart emoji to Tommy Robinson, who said Musk had funded his defence for a charge related to counter-terrorism law.

“A HUGE THANK YOU to @elonmusk today. Legend,” Robinson wrote.

It bears repeating, appearing in Epstein’s files does not establish criminality. Guilt by association is not journalism, nor is it justice.

But context is not smearing, it’s scrutiny. Examining who communicated with whom, how often, and in what capacity is a legitimate part of understanding how power operates.

There’s also the question of redaction. Many of the documents released have been heavily blacked out, names, photographs, email addresses and other identifying details obscured. In sensitive criminal cases, redaction is both necessary and appropriate, particularly to protect victims.

In some instances in the Epstein files, the reasons are obvious. Yet, as the Conversation has observed, “the absence of any reason for the redaction has simply added fuel to the fire, with spectators filling in the blanks themselves.” When transparency is partial and unexplained, it can deepen suspicion rather than resolve it.

The public release of the Epstein files was presented as a milestone for transparency. Instead, it has prompted further questions: about how sensitive material was handled, about the criteria used to withhold information, and about the extent of Epstein’s connections to powerful political figures, including figures on the far-right in the UK. If Epstein’s networks provided introductions, cross-border access, or even financial pathways into political movements, that is a matter of legitimate public interest.

More broadly, the scandal raises structural concerns. What channels enable wealthy outsiders to cultivate influence across government, academia and media? How rigorously are those relationships scrutinised? And what safeguards exist to ensure political outcomes are not quietly shaped by individuals whose interests diverge sharply from the public good?

These are not questions of insinuation, but of accountability, and in the unresolved story of Brexit, accountability remains in short supply.

Gabrielle Pickard-Whitehead is author of Right-Wing Watch

Misogyny, Epstein and Reform’s cultural agenda

6 March, 2026

From Epstein’s web to Reform’s proposed raft of policy ideas, creeping misogyny now risks redefining women’s rights in Britain

Pampered by the press as ‘the next government in waiting’, Reform continues to poll strongly. We’re familiar with how the party fosters racism through its hostile rhetoric and flagship immigration stance, but its ubiquitous misogyny receives less attention. A Reform win at the next general election will be partly because enough people either didn’t know, or didn’t care, about its views on females. For International Women’s Day, I’d like to explore these views through the lens of the Epstein files.

The octopus

The web of Epstein’s influence, in all its vast complexity, is now coming into full view, like a multi-armed, gigantic octopus being lifted from the seabed. We’re seeing Epstein the enabler, matchmaker, wheel-oiler, and co-ordinator extraordinaire in a multidimensional kleptocratic network of corporate, political, cultural and sexual interest.

You’d need a 3-D modeller to trace the complex inter-connections he orchestrated between climate denialists, fossil fuel industries, political lobbyists (Brexit, the Kremlin) the tech broligarchy, racists, eugenicists, Israeli intelligence, and more, all whilst supplying a deadly pipeline of women and child victims to the depraved subculture he cultivated. It’s all coalescing into one repulsive integrated whole.

Network participation is layered like an onion with peripheral involvement shading into roles that have varying degrees of knowledge and whistle blowing capacity on Epstein’s darkest activities. We may never know all the players or precisely which layers Epstein’s UK friends occupied. But only the outer layer is free of guilt by association of colluding with a monster.

The web of Epstein’s influence, in all its vast complexity, is now coming into full view, like a multi-armed, gigantic octopus being lifted from the seabed. We’re seeing Epstein the enabler, matchmaker, wheel-oiler, and co-ordinator extraordinaire in a multidimensional kleptocratic network of corporate, political, cultural and sexual interest.

You’d need a 3-D modeller to trace the complex inter-connections he orchestrated between climate denialists, fossil fuel industries, political lobbyists (Brexit, the Kremlin) the tech broligarchy, racists, eugenicists, Israeli intelligence, and more, all whilst supplying a deadly pipeline of women and child victims to the depraved subculture he cultivated. It’s all coalescing into one repulsive integrated whole.

Network participation is layered like an onion with peripheral involvement shading into roles that have varying degrees of knowledge and whistle blowing capacity on Epstein’s darkest activities. We may never know all the players or precisely which layers Epstein’s UK friends occupied. But only the outer layer is free of guilt by association of colluding with a monster.

Creeping patriarchy

The island of Little Saint James was the black heart of Epstein’s misogyny, but the objectification and dehumanisation of females there was driven by a culture of extreme patriarchy – the presumed superiority and dominance by males over females. Patriarchal attitudes are tightly embedded in far-right thinking and are central to viewpoints such as Christo-fascism where they fuse with Christianity, authoritarianism and white, right-wing nationalism.

This regressive ideology lurks in Project 2025, in the Christian nationalism of JD Vance, Stephen Miller and in far-right parties across central and eastern Europe. It calls for a return to a traditional Christian heterosexual, patriarchal family model in which the primary responsibilities of females are homemaking, procreation and subservience to the male family head. For ‘guidance’, listen to pastor Dale Partridge’s homily on, amongst other things, why a women’s vote must never cancel her husband’s.

Handmaids UK

Extreme patriarchy is also spreading its tentacles in the UK via organisations such as Jordan Peterson’s Alliance for Responsible Citizenship (ARC). Linked to the right-wing think tank Legatum, ARC emphasises traditional gender roles and women’s duties as breeders.

Patriarchy is very much alive and kicking within Reform. Its intrepidly retrograde Christian nationalist policy creators, James Orr, Danny Kruger and Matthew Goodwin, are currently defining Reform’s cultural agenda in patriarchal terms straight from the wider Christo-fascist comfort zones they share.

Orr opposes abortion in all cases and pushes the pro-natalist policy of families having more children “to boost birth rates”. Kruger, also a keen pro-natalist, personally supports the reversal of no-fault divorce. He wants a ‘reset to sexual culture’ and challenges the rights of pregnant women to ‘absolute bodily autonomy’. Goodwin wants a “biological reality check” for girls and tax increases for childless couples.

Securing the property

Goodwin recently opined that the “sexual exploitation of women and girls is because of open borders”. This devious but false claim uses a supposed threat to females s to attack the liberal left, but arguably, also suggests unspoken proprietorship – we must ‘protect our women and girls’ to end foreign interference with our property.

In an equally stunning patriarchal vein, Farage, who endorsed Andrew Tate as an “important voice”, describes men as ‘more willing than women to sacrifice family life for career’, and objects to the 24 week abortion limit as “ludicrous”.

To enshrine women’s demotion to second class citizens, Reform has pledged to drop the 2010 Equalities Act which provides legal recourse for maternity leave, sexual assault, domestic abuse and employment discrimination. Reform also plans to ditch the ECHR thus thwarting its use by women as another court of appeal. You can hear the sound of doors closing.

All these narratives call for controls on women’s mental, physical and developmental freedom and autonomy and constitute a clear attack on women’s rights.

‘But’, the Reform curious wail, ‘we want change – migrants and Labour must be punished and removed. So, we’ll take the US route and ignore Reform’s misogyny as non-serious, or too unpopular to survive’. Left-leaning progressives join the dismissive fray, insisting that culturally, Britain has moved on from this hopelessly backward-facing misogyny.

Yet Reform is unashamedly pushing back with their patriarchal narratives. Why?

One reason is sheer manospheric arrogance combined with the belligerence of a party looking set for power – the macho ‘just try stopping us’ mindset.

Another is that Reform’s ideas are still camouflaged. ‘Resetting sexual culture’ could mean any number of abuses of women’s rights once Reform is in power, but, for now, can be trained on DEI and LGBTQ issues which reverberate with the right-wing electorate. Similarly, ‘reversing no-fault divorce’ is just Kruger’s “personal view” – for now. Farage’s abortion concerns only imply the need for minor tweaking – for now. And pro-natalism links nicely with great replacement anxieties whilst sounding mildly patriotic – heroic Brits can keep non-whites at bay by breeding more.

The ambiguity of Reform’s statements provides space for moderation whilst simultaneously positioning the party for much more full-throated future iterations of misogynist ideas. Orr’s advice that Reform should “hold its cards close to its chest” and keep certain operations under wraps before entering government reminds us that the party’s position isn’t static.

Yet Reform is unashamedly pushing back with their patriarchal narratives. Why?

One reason is sheer manospheric arrogance combined with the belligerence of a party looking set for power – the macho ‘just try stopping us’ mindset.

Another is that Reform’s ideas are still camouflaged. ‘Resetting sexual culture’ could mean any number of abuses of women’s rights once Reform is in power, but, for now, can be trained on DEI and LGBTQ issues which reverberate with the right-wing electorate. Similarly, ‘reversing no-fault divorce’ is just Kruger’s “personal view” – for now. Farage’s abortion concerns only imply the need for minor tweaking – for now. And pro-natalism links nicely with great replacement anxieties whilst sounding mildly patriotic – heroic Brits can keep non-whites at bay by breeding more.

The ambiguity of Reform’s statements provides space for moderation whilst simultaneously positioning the party for much more full-throated future iterations of misogynist ideas. Orr’s advice that Reform should “hold its cards close to its chest” and keep certain operations under wraps before entering government reminds us that the party’s position isn’t static.

Human shields

Reform can challenge accusations of misogyny by pointing to women in its senior party roles. But this defence has no more clout than Trump trying to deny his own blatant misogyny but listing the fawning Barbie doll chatbots in his administration. Arguably, women in Reform are serving, like Reform’s non-white cabinet members, as useful pre-election human shields for a party that’s essentially riddled with racist and misogynistic elements.

The misogynist attitudes driving Reform are reason alone for women across the political spectrum to heed what supporting Reform might mean for them, and to recognise what a dangerous backward step it would be.

But we should also recognise that Reform’s misogyny sets a cultural tone of readiness for Epsteinian abuse by providing a direct pathway from regressive, patriarchal policies to sexual exploitation.

Epstein’s network reveals how the corrupting influence of power is a gateway drug for depravity. With excess power, whether as elites or via the privileges of patriarchy, players disengage from norms and stray further afield. Favours, financial rewards and the secrecy of illicit deals create useful bonds for kompromat and further corruption.

Epstein’s network is a forum for experimentation and risk taking, both financially and morally. ‘Getting away with it’ by stepping beyond legal red lines is a self-substantiating way for the patriarchal order to continually reassert control, dominance and virility. The Trump regime’s coercion of leaders and nations, like the abuses on Epstein’s island, are all ways of exercising the same male supremacist drive across different spheres. Epstein’s sex traffickers and guests parallel Trump’s sadistic geopolitical harassment of Greenland and Volodymyr Zelenskyy – ‘you will suffer (more) if you disobey’.

Life support machines

Reform policy is being forged against a transnational backdrop of extreme patriarchy. This framework is the quiet kick-off for Epstein’s darker world.

The research is clear that patriarchal conceptions of women’s role are intimately linked with sexual abuse. Patriarchal values are ingrained in power dynamics, gender hierarchy, and societal norms which drive gender-based iniquities and contribute to the perpetuation of sexual violence (Murnen et al, 2002; Spencer et al, 2023; Trottier et al, 2019).

The Epstein files are strewn with heinous crimes against females, including “sexual slavery, reproductive violence, enforced disappearance, torture, and femicide”. It’s a world in which, as Virginia Giuffre’s memoir testifies, women and children are discardable commodities and legitimacy is given to ‘those who get high on making others suffer’.

The determination of Reform’s policy setters to weaken the infrastructure underpinning women’s equality and rights over their own bodies, once realised, risks dehumanising and corralling women back into their historical dual roles of procreation and sexual pleasure. Projects like pronatalism come together with Epstein in the perception of females as essentially abusable life support machines for babies and vaginas.

I’m not, for a moment, implying that Kruger and co indulge in Epsteinean depravity. But I am asserting that he, along with Goodwin, Farage and other Reform policy creators, are re-positioning society in ways that orientate male thinking towards a future of increased sexual abuse.

Pushback vs forward movement

We should be as deeply alarmed by Reform’s misogynist elements as we are by its racist tendencies, climate denialism and attacks on workers. Women are directly affected because Reform potentially poses an acute, existential threat directly to them.

Epstein was not an aberration. Both he and Reform’s policy makers are hitching a ride with a far more ancient, long-standing misogynistic mindset spanning human history. Reform is part of a clamour across the global far right to push back against threats to white male supremacy. If Reform wins power, regressive misogyny risks being normalised again, encouraging chauvinist males to push boundaries ever further, taking advantage of new norms and tolerance levels.

The issue is not about whether parliament would retain the power of veto over the roll out of Reform’s misogynist policies. It’s about how dangerous it is even to give these ideas any traction in the first place by letting Reform win power. These are not battles that 21st century Britain, as a supposed beacon of human rights, should be having. Women must come together on International Women’s Day and beyond to halt this menace.

This article was first published on the Bearly Politics Substack on 4 March 2026