Becoming the Monster: Imperial Anxieties and the Birth of the Racialized Vampire

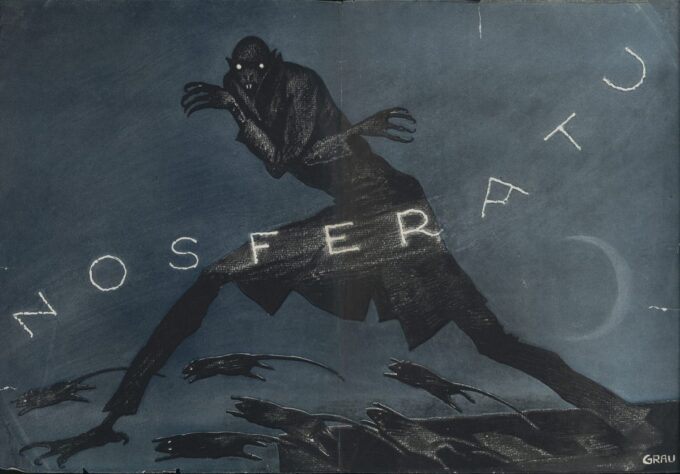

German promotional material for Nosferatu – US PD

Both Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) and its German cinematic adaptation Nosferatu (1922) project the vampire as a racialized and cultural Other, a figure onto which the anxieties of imperial decline, xenophobic paranoia, and racial-political fantasies are mapped. In these texts, the vampire is not merely a supernatural being, but a vessel for deeper fears about reverse colonization, cultural infiltration, and contamination. This racialization of the vampire unfolds in distinct historical stages, from the imperial imaginary of the late 19th century to the racial visual codes of interwar European cinema.

In Stoker’s Dracula, the eponymous figure represents a complex form of otherness rooted in both geographical and cultural displacement. Though the novel is situated in London, Count Dracula originates from Transylvania, a region that was often coded in 19th-century Britain as part of a vague and threatening East.

Dracula’s knowledge of British culture, law, and customs, initially charming to Jonathan Harker, soon becomes a source of fear as it reveals a strategic appropriation designed to penetrate and exploit the British Empire from within. This fear of reverse colonization is central to the novel’s horror: the imperial subject finds itself vulnerable to the very tools it used to dominate others. Inverting the colonial missionary enterprise, Dracula becomes a figure of counter-knowledge, using the West’s languages, geographies, and rationalities against it. Stoker underscores this destabilizing globalism through Van Helsing’s observation that vampire lore spans civilizations – from Greece and Rome to India and China – situating the threat as global, migratory, and non-European. This aligns the Count with what can be termed the “Oriental Other”, designating how Western powers construct foreign identities in order to reinforce their own superiority and coherence.

The enduring threat posed by Count Dracula as an Other is reflected not just in the novel’s initial success, but in its dramatically heightened popularity in the years following its publication. As the British Empire reached its zenith and simultaneously became more anxious about its durability, readers and audiences increasingly identified with the novel’s dramatization of boundary collapse. After World War I, the novel found renewed popularity through a series of adaptations that brought its themes into mass culture. The stage version by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston premiered in 1924 and found major success on London’s West End by 1927. The American version starring Bela Lugosi followed on Broadway the same year, translating the Count into a transatlantic myth of infiltration. It was in this charged cultural atmosphere that Nosferatu, directed by F.W. Murnau in 1922, reimagined the vampire narrative within a distinctly German cinematic language of racial threat.

In adapting Dracula, Nosferatu changes both names and settings. Count Dracula becomes Count Orlok, and the narrative is transported to the fictional German town of Wisborg to avoid copyright infringement. But more importantly, Nosferatu radically transforms the visual and semiotic function of the vampire. While Stoker’s Dracula could pass for an aristocratic human, Count Orlok is immediately monstrous: bald, gaunt, hunched, with elongated fingers and a prominent hooked nose. These features align with anti-Semitic visual tropes that were widespread in Weimar Germany, where Jews were frequently depicted in caricatures as vermin-like, parasitic, and racially degenerate. Orlok’s rat-like movements, association with plague-bearing rodents, and physical grotesqueness all participate in this visual economy of racial fear.

Thus, Orlok does not merely continue the tradition of the orientalized outsider; he becomes, more specifically, a racialized threat coded in anti-Semitic terms. The fact that he must travel with the soil of his homeland, and that his destruction is accompanied by the destruction of his castle, suggests a fantasy of national purification through the elimination of foreign contaminants. The final shot of Orlok’s destroyed homeland implies that his evil was not only personal but civilizational. Orlok’s grotesque, rat-like body embodies the racialized Other while his distant, decaying castle evokes the Orientalized East, a symbolic homeland of foreign corruption. The film stages the destruction of both. That Orlok is ultimately destroyed by the pure, self-sacrificing figure of Ellen further reinforces this racialized morality: the national community can only be saved through the eradication of the Other by means of sacrificial innocence.

Ellen’s Descent: From Symbolic Purity to Sexual Transgressor

In this ideological framework, Ellen serves as the moral opposite of the racialized Other: a passive, self-sacrificing woman whose purity redeems society. However, the 2025 remake radically reimagines her character, shifting the logic of purity and monstrosity and ultimately rendering Ellen an Other in her own right.

Nosferatu (1922) portrayed Ellen in a completely stereotypical light. The only way to defeat the monster is for an “innocent maiden” to sacrifice her life by allowing him to drink her blood. Ellen sacrifices herself to save everyone else, even though she has nothing to do with the plague. From the beginning of the movie, she is bathed in sunlight as she plays with a kitten and cries over plucked flowers, all of which are symbols of her purity. The director of the 2025 remake, Robert Eggers, consciously sought to change this. In what can be seen as a decidedly feminist revision, Ellen initiates a relationship with Nosferatu because she is desperately lonely within a patriarchal order. However, she soon discovers that Nosferatu turns all her pleasure into pain, for he is a force of darkness. After this, she settles down with Thomas Hutter and lives peacefully with him until Nosferatu returns to claim her, having made her promise to be eternally his.

Unlike the earlier version, Ellen here embraces the darkness from the beginning and is more in control of it than those around her. It is because of this that others misunderstand her. Yet she is not a passive victim. She speaks out against those who disbelieve her, who tie her up and call her mad, even against her husband, whom she loves. She criticizes him for going on a “fool’s errand” against her wishes and asks where the wealth is that he was supposed to bring. Instead of bringing home any riches, she accuses him of having sold her for gold.

However, like in the older film, she too sacrifices herself in the end. She is made to feel ashamed of her actions by society. Her ultimate sacrifice seems to come too late because Anna and her children, who had treated her with kindness, are already dead. Anna had been just like Ellen in the 1922 version: a loving mother and wife. She sympathizes deeply with Ellen, and it is only because of her kindness that Ellen is not turned out of the Harding household by her husband. After Anna’s death, Ellen feels it is her duty to save the city by ending her own life. In doing so, perhaps she too can be considered virtuous, just like Anna, even at the cost of her own life.

In the end, Ellen seems to be conforming to an ideal set by women like Anna. She may have spoken back, expressed her sexuality, and shown emotion more freely, but ultimately, the fate of her town and her loved ones depends on her refusal to “let her lower animal functions dominate,” as Von Franz once said of her.

In this way, Ellen too becomes an Other. While the 1922 Ellen had no transcendental connection with anyone but Hutter, the 2025 version gives her a deep connection with Nosferatu. In the earlier film, as Orlok is about to attack Thomas, Ellen screams his name, and Orlok withdraws, suggesting she possesses some moral force that protects her husband. In the new version, Ellen has no such moral power. In fact, while speaking to Thomas, she says, “He told me about you. He told me how foolish you were. How fearful. How like a child. How you fell into his arms as a swooning lily of a woman.” As Alisha Mughal writes,

“As much as the Count represents a racial ‘other,’ Ellen represents a sexual other. While Ellen is not a vampire specifically within the story, she is a ‘blot on the human conscience’ in the sense that she has always been her animalistic self—a strain first on her father and his household, and then on the Harding household, a strain on the finances of a successful, civilized man. She is everything a proper woman in her society ought not to be: loudly insane, experiencing paroxysms that even a corset cannot contain. She sleepwalks, weeps incessantly, and experiences verboten sexual desires.”

Ellen recognizes that she is the Other and is filled with shame. She does not want to be anything like Nosferatu. Unlike him, however, she is the constructed Other. She can choose to be human. She can choose to rejoin society, even if it’s the only choice left to her. The foreign outsider is born an outsider and will forever remain so. Ellen becomes an outsider through transgression but ultimately must return and draw the line between the morally upright white civilization and the sexually aggressive Other. Nosferatu’s otherness is naturalized, it is inherent to him, written into his very body. He is the essential Other. Unlike Ellen, he has no society that casts him out because he was never part of it to begin with. When Orlok first meets Ellen in Wisborg, she tells him that he cannot love, and he agrees, as if he were made that way.

Orlok vs. Heathcliff: Two Visions of the Gothic Other

Eggers has said that one of the major inspirations while writing the Nosferatu (2025) script was Wuthering Heights, as he saw a similarity between Heathcliff and Count Orlok. However, while Heathcliff is an Other, he is not an essential Other. Unlike Orlok, whose monstrosity is depicted as innate, Heathcliff’s demonization stems from the way he is treated by those around him. From the moment of his arrival at Wuthering Heights, he is subjected to abuse, especially by Hindley. After the death of Mr. Earnshaw, Heathcliff is forced into servitude, denied an education, and made to labor in the fields. As Nelly observes,

“He seemed a sullen, patient child; hardened, perhaps, to ill-treatment: he would stand Hindley’s blows without winking or shedding a tear, and my pinches moved him only to draw in a breath and open his eyes, as if he had hurt himself by accident, and nobody was to blame.”

By being continually portrayed as demonic and subhuman, Heathcliff gradually transforms into the image others have imposed upon him. He conforms to the role society assigns him, not because he is inherently monstrous but because monstrosity is the only way left to assert agency. In Wuthering Heights, the figure of the Other functions not as a permanent outsider, but as a mirror reflecting society’s own prejudices and contradictions. For example, when Catherine tells Nelly about a dream in which she goes to heaven and feels utterly miserable, only to be cast out by the angels and return joyfully to the earth, it reveals how the Other disrupts conventional notions of order and moral idealism. Catherine understands that she becomes an Other by loving Heathcliff and she chooses to marry Edgar Linton, believing that doing so would help both herself and Heathcliff materially.

However, Heathcliff overhears only the part where she says that marrying him would degrade her, and leaves before hearing her declare her love and insist that nothing would separate them. He returns years later, wealthy and vengeful, not against Catherine but against those he holds responsible for keeping them apart. His revenge extends to Linton’s daughter and Hindley’s son, targeting the next generation. Meanwhile, Catherine, torn between societal expectations now that she is married to Linton and her passionate love for Heathcliff, spirals into madness and dies. Even as Heathcliff seeks revenge, he is shattered by grief at Catherine’s death. In end, the grief overtakes him to such an extent that he cannot pursue revenge anymore. Everything reminds him of Catherine, he wants to die so he can reunite with Catherine and his wish is ultimately fulfilled when he dies of starvation after refusing to eat for several days. He sees death as the only means to reunite with Catherine, showing that he is capable of love, unlike Orlok.

Where Orlok is essentialized as the Other and denied interiority, Heathcliff’s Otherness is a product of social exclusion, classism, and cruelty. His monstrosity is not innate but reactive. It is a human response to inhuman treatment. As Adele Hannon has said,

“Placing a magnified lens on the acts of monstering the Other and the dislikeable aspects of humanity will show how observations of the cultural Other are rendered incomplete, as any true understanding of the Other will locate them outside the realm of unknowable and unfamiliar, making the subject harder to dehumanise and marginalise. Even though Heathcliff is without a narrative voice or any distinct identity, his actions speak to many transgressive ideas concerning gender, otherness and understandings of the abject. Where he lacks in definition, his obscure identity allows Brontë’s audience to displace their own trauma onto this tragic gothic villain. Thus, the once unfamiliar Other is exposed to share a familiar face to the differing insecurities of the reader.”

Ultimately, Orlok and Heathcliff embody two opposing visions of the Other. Orlok is essentialized: monstrous by nature and irredeemable, while Heathcliff’s Otherness is constructed through cruelty and exclusion. While Orlok is denied interiority, Heathcliff is haunted by it, capable of love, grief, and moral ambiguity. He does not embody evil but reflects the violence of a society that creates its own monsters, revealing that the true horror lies not in the foreign invader, but in the civilizational gaze that defines, distorts, and ultimately destroys those it deems unworthy of belonging.