The High Seas Treaty signals a “new era of global ocean governance”, but experts warn that it will not stop irreversible damage.

The highly anticipated High Seas Treaty has come into force today, marking a “historic milestone” for global ocean conservation.

Covering almost half of the planet’s surface, the High Seas lie beyond national borders and form part of the global commons. Until now, there was no legal framework dedicated to protecting biodiversity in these international waters and ensuring the benefits of their resources were shared fairly among nations.

However, following decades of negotiations, a Treaty text was finalised in March 2023, setting clear obligations on how to ensure ocean resources are used sustainably. To come into effect, 60 country ratifications (final approval and consent to be legally bound by a treaty) were required – a milestone that was achieved on 19 September last year.

While experts have praised the agreement as a “turning point” for multilateral cooperation and ocean governance, concern remains around potential loopholes.

What are the High Seas, and why are they so important?

The High Seas is often used to describe all areas beyond national jurisdiction, including the seafloor and water column (the vertical section of water from the surface to the bottom). This equates to international waters that cover more than two-thirds of our ocean - almost 50 per cent of the planet’s surface area.

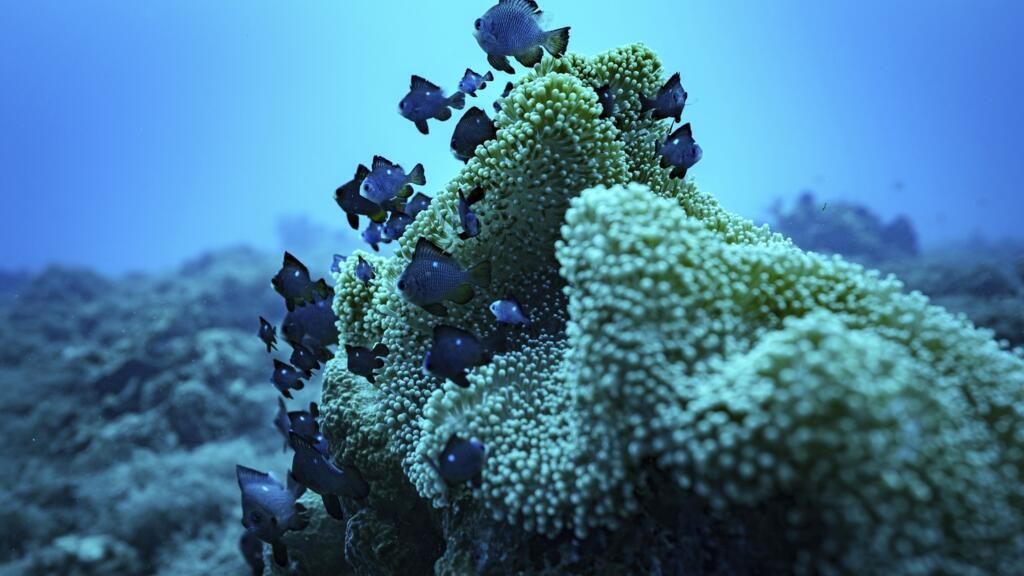

Once considered barren and desolate, scientists now regard the High Seas as one of the largest reservoirs of biodiversity on Earth. It plays an important role in regulating the climate, supporting “crucial” carbon and water cycles.

In fact, it is estimated that the economic value of carbon stored by the High Seas ranges from $74 billion (around €63.62 billion) to $222 billion (€190.85 billion) per year.

However, human activity poses a growing problem for the High Seas. According to the High Seas Alliance (HSA), which advocated for the treaty, destructive fishing practices such as bottom trawling and illegal fishing are harming High-Seas marine life.

This, combined with plastic and chemical pollution, emerging activities such as seabed mining, and waters being acidified by rising temperatures, puts the High Seas under severe threat.

What will the High Seas Treaty do?

Now international law, the Treaty will empower nations to establish a connected network of High Seas marine protected areas (MPAs) - which can be adopted by a vote when consensus cannot be reached. This helps prevent a single nation from blocking MPAs being established.

It also supports developing countries through capacity building and the transfer of marine technology so that they are better empowered to develop, implement, monitor and manage future High Seas MPAs.

Several legal obligations apply from today. For example, any planned activity under a Party's control that could impact the High Seas or seabed must follow the Treaty’s environmental impact assessment process, and governments need to publicly notify such activities.

Parties must also promote the Treaty’s objectives when participating in other bodies such as those that govern shipping, fisheries and seabed mining.

“At this halfway point of this critical decade, one of the world’s most ambitious ocean initiatives is entering a new era of systemic change in ocean governance,” says Jason Knauf, CEO of The Earthshot Prize.

“This reflects a renewed commitment to our ocean, its wildlife, the millions of people that rely on its health, and the global goals set for 2030. The High Seas Treaty shows us that meaningful progress is achieved through vision, perseverance and leadership.”

Will our oceans be properly protected?

While the High Seas Treaty has been praised by governments, NGOs and environmentalists around the world, concern still surrounds how effective the agreement will be in protecting our oceans.

“Today is a day of celebration for biodiversity and multilateralism, but the job of protecting the ocean is far from complete,” says Sofia Tsenikli of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition (DSCC)

“The High Seas Treaty raises the bar significantly, but on its own, won’t stop deep-sea mining from beginning in our ocean.”

Several countries that ratified the High Seas Treaty, such as Japan and Norway, have shown interest in digging up vast stretches of the seabed in the race for critical minerals used in green technology.

“Governments cannot credibly commit to protecting marine biodiversity while allowing an industry that would irreversibly destroy life and ecosystems that we barely understand to proceed," Tsenikli adds.

A recent deep-sea mining test found that the controversial practice impacts more than a third of seabed animals, while a report published in 2024 by the Environmental Justice Foundation found that deep-sea mining is not actually necessary for the clean energy transition.

It’s why the DSCC is calling on all members of the High Seas Treaty to use its momentum to establish a deep-sea mining moratorium at the International Seabed Authority.

Dr Enric Sala, founder of Pristine Seas, also warns that the Treaty cannot overlook the value of protecting ocean areas that belong to national governments, as this is where most fishing and other damaging human activities take place.

In a statement, he says the protection of national waters "cannot be put on the backburner”.

“New MPAs – whether they’re established in the High Seas or nearshore – will only be effective if they are strictly protected and fully monitored for illegal activity,” Dr Sala adds.

“This is the only way we can ensure that marine reserves deliver benefits to climate, biodiversity and economies.”

Stronger protection for marine life as

landmark law takes hold on high seas

For decades, vast stretches of ocean beyond national borders have been governed by patchwork rules and weak oversight. On Saturday, that changes. The High Seas Treaty enters into force, creating the first legally binding global framework to protect marine life in international waters that span nearly half the planet.

Issued on: 17/01/2026 - RFI

By:Amanda Morrow

Known as the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement, the treaty gives countries a shared legal toolbox to conserve and manage the parts of the ocean that belong to nobody.

After almost 20 years of marathon negotiations, the United Nations adopted it in June 2023. In September, Morocco became the 60th country to ratify the treaty, triggering the countdown to it becoming law. More countries have joined since.

Conservation groups say its long-awaited rollout marks a shift from ambition to obligation.

Nations that have ratified the agreement must begin applying a set of legal duties to protect marine life – even as key institutions are still being built.

Once thought to be lifeless, the high seas are now known to host extraordinary biodiversity, from deep-sea corals to migratory species that travel vast distances across the ocean.

They also play a critical role in regulating Earth's climate. The ocean absorbs around 30 percent of carbon dioxide emissions and more than 80 percent of the excess heat they generate, helping to slow the pace of global warming.

But scientists warn that this vast ecosystem is under growing pressure from human activity – including fishing, pollution and climate change – that often happens far from public view.

An ocean beyond borders

The high seas are the open ocean and deep seabed beyond countries’ exclusive economic zones. They make up about two-thirds of the ocean and nearly half of Earth’s surface.

Despite this extraordinary scale, less than 1 percent of the high seas is currently protected.

One of the treaty’s most anticipated outcomes is the creation of marine protected areas, where human activities would be limited or banned to allow ecosystems to recover.

The treaty sets out a formal process for proposing and adopting these areas, including scientific review and consultation. While final decisions will be taken by the Conference of the Parties, or BBNJ Cop – due to be held within the treaty's first year – countries can already begin preparing proposals.

The High Seas Alliance, a coalition of conservation organisations, has identified several places that could form a first generation of protected areas. They include the Emperor Seamounts, a chain of underwater mountains in the Pacific; the Sargasso Sea, a biologically rich area of the Atlantic; and the Salas y Gomez and Nazca ridges, a vast seafloor region off South America.

“For the first time, the global community has a legal mechanism to protect the parts of the ocean that belong to no one state,” said Kevin Chand, director of Pacific ocean policy at Pristine Seas, an ocean conservation programme of the National Geographic Society.

Chand also pointed to the role of Pacific countries in pushing negotiations over the line, saying their “bold leadership” helped turn a vision into law.

New obligations

While some of the treaty’s bodies are still under construction, a range of obligations apply immediately. Countries that have ratified must promote the treaty’s conservation goals when they take part in decisions at other international ocean bodies – including fisheries, shipping and seabed authorities.

They must also begin cooperating on marine scientific research, technology transfer and capacity building, particularly with developing countries.

Planned activities under a country’s control that could harm marine life in international waters must now undergo environmental impact assessments that meet the treaty’s standards.

The agreement also introduces new reporting and transparency rules around marine genetic resources – genes from plants, animals and microbes that could be used in research or commercial products such as medicines.

Countries must start signalling the collection and use of these resources and sharing non-monetary benefits such as data and access to samples.

A global test of follow-through

Enric Sala, founder of Pristine Seas and a National Geographic explorer, warns that protection on paper will not be enough.

“New marine protected areas – whether they are established in the high seas or near shore – will only be effective if they are strictly protected and fully monitored for illegal activity,” he said.

“This is the only way we can ensure that marine reserves deliver benefits to climate, biodiversity and economies.”

The treaty does not automatically protect any part of the ocean – nor does it override existing bodies that regulate fishing, shipping or seabed mining. Instead, it relies on countries to align their decisions with the new conservation framework.

Supporters say this means that political will, funding and widespread participation will be critical. Only countries that ratify the treaty are legally bound by its rules, but wider uptake will be needed if it is to work as intended.

For now, Saturday marks the start of a new phase. After years of negotiation, scientists say the challenge now centres on cooperation and whether countries will actually use the tools they have given themselves.

By AFP

January 16, 2026

After years of delay, the treaty to protect the high seas was ratified in September with the approval of 60 countries - Copyright AFP/File Sameer Al-DOUMY

China on Friday proposed to host the secretariat of a new treaty governing the high seas, a surprise bid that underscores Beijing’s desire to have greater influence over global environmental governance.

China “has decided to present its candidature of the city of Xiamen to host the Secretariat” of the treaty, the Chinese mission to the United Nations wrote in a letter to Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, according to a copy seen by AFP.

The treaty will officially enter into force on Saturday, and the host country of the eventual secretariat will be decided later this year.

Until now, Belgium and Chile had been vying to host the future organization.

The Xiamen bid signals “China’s intention to help shape global rules,” said Li Shuo, director of the China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute in Washington, calling it a “notable move.”

China’s announcement came just days after US President Donald Trump announced his country will withdraw from 66 global organizations and treaties — involving UN and non-UN entities.

They include the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the parent treaty underpinning all major international climate agreements, ratified by almost every country in the world.

After years of delays, the treaty to protect the high seas was ratified in September by 60 countries. The law aims to protect biodiverse areas in waters worldwide, extending beyond countries’ exclusive economic zones.

Teeming with plant and animal life, the oceans are responsible for creating half of the globe’s oxygen supply and are vital to combatting climate change, conservationists say.

Once the treaty becomes law, a decision-making body will have to work with a patchwork of regional and global organizations already overseeing different aspects of the oceans.

These include regional fisheries bodies and the International Seabed Authority — the forum where nations are jousting over proposed rules on the environmentally destructive deep-sea mining industry.