Nijmegen, 10 December 2025 - More than a decade after the first Neanderthal genome was sequenced, scientists are still working to understand how human-specific DNA changes shaped our evolution. A new study by the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, published in Science Advances, offers an innovative approach: by scanning DNA of hundreds of thousands of people in a population biobank, researchers can identify individuals who carry the very rare archaic versions of these genetic changes, making it possible to directly observe their real-world effects in living humans.

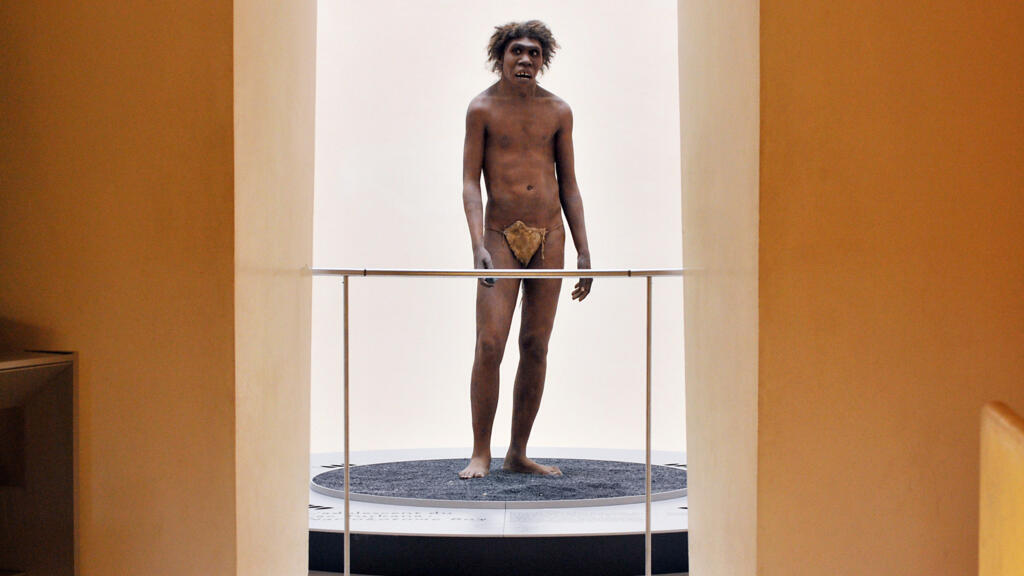

It’s just over a decade since scientists first reported successfully sequencing the virtually complete genome of a Neanderthal, a landmark in ancient DNA research. Although present-day humans are not the direct descendants of Neanderthals, we shared a common ancestor with them roughly 600,000 years ago. By comparing modern genomes to those of our extinct Neanderthal cousins, it became possible to assemble a catalogue of human-specific DNA changes that arose uniquely on the branch that led to us. But we still know little about the roles these DNA changes played (if any) in our evolutionary story.

An innovative source: Population databases like UK Biobank

In prior research, scientists were largely limited to testing the impacts of human-specific genomic changes by either “humanizing” animal models or introducing archaic (i.e. ancestral) DNA variants into human tissue grown in the laboratory. The authors of the new study reasoned that complementary insights might instead come from an innovative source – population biobanks.

“Research suggests that genetic variants with relatively recent origins in human evolution could be especially relevant for health outcomes, so the availability of massive collections of data from hundreds of thousands of human participants gives exciting new opportunities” says Barbara Molz, one of the lead authors of the study. “By searching biobanks like these for very rare cases where individuals happen to carry archaic versions of human-specific DNA changes, we get the chance to study their potential real-world effects directly in living people.”

Human-specific changes not as universal as thought

To demonstrate promise and pitfalls of this new strategy, Molz and co-authors targeted one class of DNA changes that has received particular attention in earlier research on human evolution – variants that alter protein structure. Proteins make up much of the molecular machinery of cells, with a wide array of roles in the development and functioning of our tissues and organs. The team focused on just the set of human-specific evolutionary changes which affect protein coding and which were so far thought to be unvarying (“fixed”) in all modern humans.

On thoroughly scanning DNA sequences of >450,000 people in UK Biobank, a population resource of healthy adults from the United Kingdom, the researchers found that for many supposedly fixed evolutionary changes in protein coding (17 out of 37 that could be tested), there were at least a few living individuals with an archaic version of the gene, matching the status of our common ancestor with Neanderthals. They zeroed in on one of the variants with the largest number of carriers, a variant in SSH2 – a gene which has been linked to development of brain cells, among other functions. Investigating a range of health, psychiatric, and cognitive traits in 19 unrelated individuals with archaic SSH2, they found no obvious consequences of carrying this ancient variant.

Large lab effects may not match real-world outcomes

The researchers next investigated another variant of special interest, affecting a gene called TKTL1. Big differences between impacts of human and archaic versions of TKTL1 were previously shown in experiments with animal models, gene-edited brain organoids, and gene knockouts in human foetal brain tissue. Those experiments suggested a key role for TKTL1 in our evolution, in which the human-specific change drove increased generation of neurons in frontal brain regions, with potential consequences for human cognition and behaviour.

However, when Molz and colleagues searched UK Biobank, they found there were 62 people carrying the archaic version of TKTL1. Since TKTL1 lies on the X chromosome, the males among these (16 individuals) only have the archaic variant; they completely lack a human-specific version. A subset of people in UK Biobank had undergone research-based neuroimaging, allowing the researchers to look for effects of carrying the archaic version of TKTL1 on structure of the frontal lobes of the brain. But no extreme differences were detected, even in the males. And a substantial proportion of carriers had a college/university degree, arguing against a major impact on cognitive function. The results indicate that the sometimes dramatic effects seen in lab-based experiments on evolutionary variants may not be a guide to their real-world impacts in living human beings.

Challenges and recommendations for the future

“The findings cast further doubt on the idea that distinct features of Homo sapiens might be explained by any singular genomic change with large effects on brain and behaviour,” says Simon Fisher, senior author of the new study. “Overall, this work shows how biobanking efforts can give important insights not only into health and disease, but at the same time may also help illuminate deep questions about our evolutionary origins.”

Still, the authors emphasize that major challenges remain, and they offer recommendations for how to overcome these moving forward. For example, the rarity of individuals who carry archaic variants limits sample sizes, making it difficult to exclude more moderate effects. And many population biobanks lack information about traits of particular evolutionary interest, such as language skills. In future work, there is a need also to broaden ancestral diversity in biobanking efforts, and to develop methods that can better tease apart how multiple evolutionary changes interact to shape human biology.

The research paper titled “Evaluating the effects of archaic protein-altering variants in living human adults” will be available in Science Advances after the embargo lifts and can https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ads5703 (this link won’t be active until the embargo lifts). More information, including a copy of the paper, can be found online at the Science Advances press package at https://www.eurekalert.org/press/vancepak/

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ads5703

Media contact:

Anniek Corporaal

Head of Communications

Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics

anniek.corporaal@mpi.nl

www.mpi.nl

Authors for general media enquiries:

Barbara Molz, Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Barbara.Molz@mpi.nl

Simon Fisher, Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Simon.Fisher@mpi.nl

Independent experts (not co-authors) who might comment on the work:

Cedric Boeckx (University of Barcelona), Cedric.Boeckx@ub.edu

Alex Pollen (University of California, San Francisco), Alex.Pollen@ucsf.edu

Madeline Lancaster (University of Cambridge), mlancast@mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk

Wolfgang Enard (Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich), enard@biologie.uni-muenchen.de

About UK Biobank

UK Biobank is the world’s most comprehensive source of biomedical data available for health research in the public interest. Over the past 15 years we have collected biological, health and lifestyle information from 500,000 UK volunteers. The dataset is continuously growing, with additions including the world’s largest set of whole genome sequencing data, imaging data from 100,000 participants and a first-of-its kind set of protein biomarkers from 54,000 participants. Since 2012, scientists from universities, charities, companies and governments across the world can apply to use the data to advance modern medicine and drive the discovery of new preventions, treatments and cures. Over 22,000 researchers, based in more than 60 countries, are using UK Biobank data, and more than 18,000 peer-reviewed scientific papers have been published as a result. The data are de-identified and stored on our secure cloud-based platform. UK Biobank is a registered charity and was established by Wellcome and the Medical Research Council in 2003. For more information, click here.

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

People

Article Title

Evaluating the effects of archaic protein-altering variants in living human adults

Article Publication Date

10-Dec-2025