Shutterstock Asset id: 1918280681

The Guardian reports it was largely the work of a hyper-conservative group of Mormon women who derailed Republican efforts to gerrymander a new Republican district in Utah this year.

The Pew Research Center reveals that Mormons, also known as members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, were among Trump’s strongest supporters in 2016, with about 61 percent of church members backing him, making the group his second-largest religious support base.

But in 2018, the Mormon Women for Ethical Government (MWEG) helped gather enough signatures to pass Utah’s Proposition 4, with 50.34 percent of the vote. This created an independent state commission to draw state and congressional maps using nonpartisan criteria, rather than let legislators cherry-pick their own voters.

But in 2020, state Republican lawmakers told MWEG to take a hike and repealed Proposition 4. Then they redrew maps that split Salt Lake County – Utah’s youngest, most diverse and bluest region – into four districts. This packed urban Democratic votes into red outlying regions and entrenched GOP dominance for the next election. The MWEG group sued their state government along, arguing that the Republican-led legislature violated the state constitution when it altered a legitimate voter-approved proposition.

“Last summer, the women’s groups won,” reports the Guardian. “Now state lawmakers must draw new maps that could pave the way for a Democratic congressional seat in the 2026 midterm elections.”

“I live in a district that’s likely going to become Democratic,” said MWEG Founder Emma Petty Addams. “I’ll lose a Republican representative I respect, and I’m 100 percent OK with that if it means my neighbors get representative government.”

Defying lawmakers was not easy, said Addams, a mother of three and a piano teacher. But the legal battle was necessary to deal with “an overreach of power” that Utah voters opted to protect with “guardrails”.

“People want to see Mormon women as either the secret wives or as a trad wife,” Addams said. “We’re neither of those.”

The organization’s is already saddling up for its next fight, however, as the Utah Republican Party pushes to repeal Proposition 4. In an effort to gerrymander Utah to protect Trump’s narrow House GOP majority, the party is seeking 141,000 signatures by February to place the repeal on the November ballot.

Trump posted on Truth Social, urging Utah residents to repeal the proposition and let politicians pick their own voters. This follow his nationwide effort to restructure districts to enshrine his majority for the foreseeable future — some with more success than others.

“Organizers had gathered around 56,000 signatures as of 26 January,” reports the Guardian. “The Utah Republican party did not respond to a request for comment about its repeal efforts.”

Photo by Edward Cisneros on Unsplash

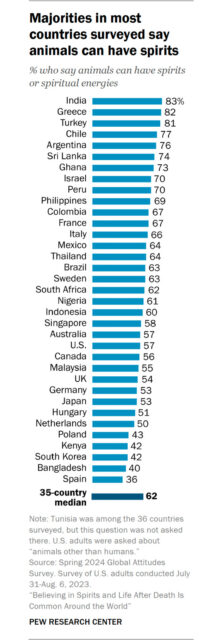

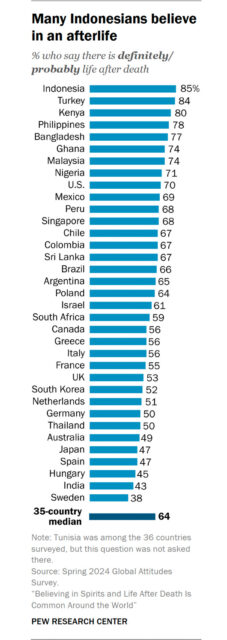

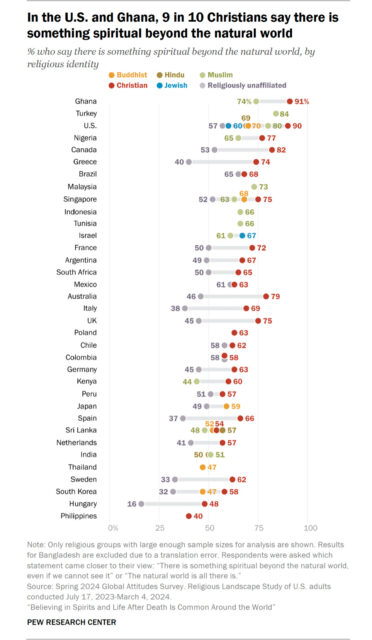

Over the years, traditional religious practice has declined in both the United States and globally, according to one political scientist.

Speaking to The New York Times' "Interesting Times" podcast, Ryan Burge, an ordained Christian minister who became a professor, analyzed data trends for his new book, "The Vanishing Church: How the Hollowing Out of Moderate Congregations Is Hurting Democracy, Faith, and Us."

The number of people declaring they aren't affiliated with any church appears to have stalled, Burge said, but this has not benefited traditional Christian churches.

Burge argues that polarization and sorting are central to the trend, with moderate, mainline Protestant churches hollowing out while more intense, ideologically defined communities remain. White evangelical congregations on the right remain comparatively stable.

Burge emphasizes that "nones" are not secretly spiritual seekers in disguise. Many are neither religious nor particularly spiritual. Instead, they reject the institutions themselves, reflecting a broader anti-establishment sentiment in the U.S.

"I think education, social trust, and institutional trust are all locked together in this matrix of things that make you either more willing to engage in polite society, or less willing to engage in polite society. Educated people have a level of trust that less educated people do not," Burge said on the podcast.

One consistent theme is that "dropping out begets dropping out." Those who drop out of church also have lower educational attainment rates. Only about 25 percent have four-year college degrees.

"So they're dropping out of education, they're dropping out of religion, and they're dropping out of politics. They're basically isolating themselves from American society," Burge said.

Unlike in previous decades, politics is shaping the religious mindset of those who do not return to the churches in which they were raised. While churches were once places where Democrats and Republicans could sit in the same pews, today people seek out others who are largely similar to themselves. Families are seeking out churches based on political alignment rather than other factors.

"What's happened in America, especially with white Christianity, is that it is coded as Republican — and that's not always been the case," Burge said. "I think this is a point that people forget: Even in the 1980s, among the white evangelical church, the share who were Republicans and the share who were Democrats was the same."

The sorting of people by similar beliefs has increased the decline of politically mixed, moderate congregations, while reinforcing the perception that white evangelical churches are an extension of the Republican Party.

"So what we're seeing here is a unique moment. The number one predictor of whether you're going to be religious or not in America — besides the religion question itself — is: What is your political ideology? If you're a liberal, there's a 50-50 chance you're a nonreligious person. If you're a conservative, it's about a 12 percent chance that you're a nonreligious person," Burge said.

Young people are most affected by political ideologies in determining religious behavior.

"Young people think, 'I'm a liberal, so I'm going to be irreligious,'" Burge said. "They don't even accept the possibility that you can be a liberal Christian anymore."

Burge noted that responses to right-wing churches have included setting up left-wing alternatives. However, mainline church members want a completely non-political space. While the Covid lockdown brought many people to watch services online, once it ended, Burge said people wanted in-person attendance. He has observed this with young people as well: only 15 percent preferred online learning, and 15 percent had no preference. The rest preferred to meet in person.

Burge concluded by saying, "Listen, religion's endured for all of Western civilization because it works for lots and lots of people. And no matter how much we try to remake it with technology and A.I. and the internet, showing up on an average Sunday with a bunch of people and singing some songs and saying some creeds and hearing a sermon is transformative and will be for all of human history, as far as I can tell."

Read or listen to the full interview here.