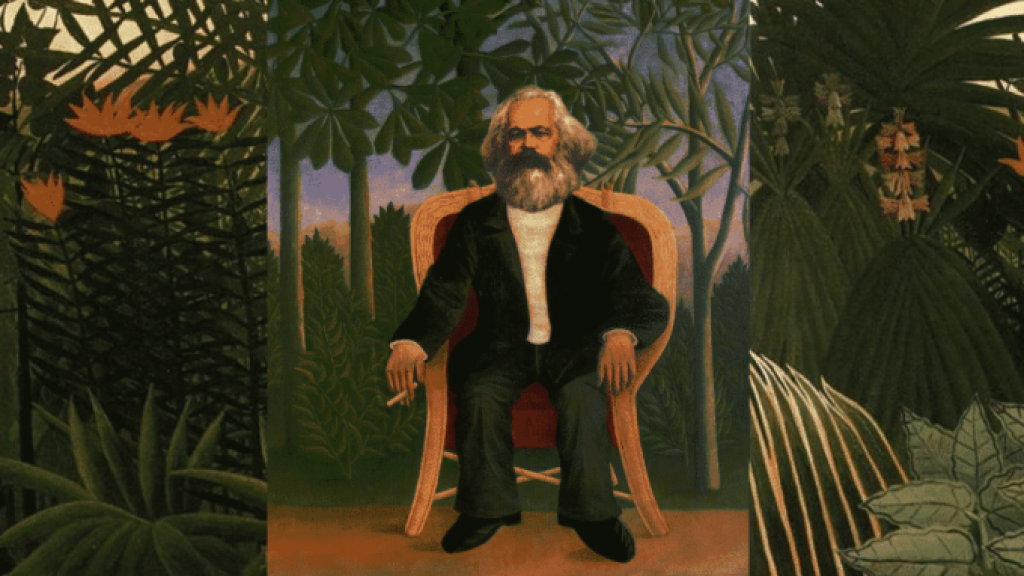

Image by “My Life Through A Lens”.

An Interview with Helia Rasti and Ashanti Alston

This interview is with social movement veterans who have sacrificed much, and learned a great deal, trying to change the world. Each in their own way have gained valuable insights into the personal, interpersonal, and structural dynamics at play when confronting established power and have essential lessons to convey to those newly radicalized. The interview was conducted for Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, by collective member Paul Messersmith-Glavin.

Paul Messersmith-Glavin: Tell us about yourselves, in particular, how were you first politically radicalized?

Ashanti Alston: Born, Michael Alston. Plainfield, New Jersey, 1954. Just this February, I celebrated the big 7-0. I’m an official elder now.

I came of age in that period of the sixties when there was the Civil Rights movement and the Black Power movement, which was the key moment for me. I was a Black teenager understanding that there were people fighting for our freedom in the Civil Rights movement. And then here comes the Black Power movement and the rebellions of ’67 all over the United States.

Plainfield is a small town that’s racially divided like so many other places. But what was unique about what happened there was that Black folks had got hold of arms from a gun manufacturing plant, including crates of M-1 rifles. So, during the rebellions part of the Plainfield Black community in the West End was actually liberated for at least seven days. Even as this thirteen-year-old, I understood the importance of the movement and felt connection to it. This was serious and way different from Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights movement.

The main rebellion was about a mile from the projects where I lived as a child. We could often hear the gunshots. Then one day there was a black car in front of the house and on the top of it in white letters was “Black Power.” And the guy in the car was giving out goods to people. That struck me, because I heard the term “Black Power,” but this was so bold. I understood the Civil Rights movement, but I didn’t know if I could deal with getting water-hosed down the street, spat on, called “nigger” in my face and just taking it. I wanted to fight back. So, this was my entry.

I don’t even think I had turned fourteen yet. And I wasn’t much of a reader at that point, but now I wanted to read! The Malcolm X autobiography. The stories of Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown. I wanted to go find out about them. Then when school started back up, others were also interested in fighting back. In junior high school there was no Black history. So, there was a coordinated effort to walk out of the two junior high schools and the high school and to march down to City Hall to demand it. And enough of us came out, so that when the next school year started, we had Black history.

That showed me that there was this powerful unity if we organized. We could make demands and have them met. The rebellion after that lasted a week. When the armored cars came in from the National Guard, they regained control. But it didn’t stop us. The was a community center down the street and folks were in there and they’re talking, organizing, strategizing. I was just so excited, especially to see folks from the areas that I grew up who I looked up to in getting involved.

Eventually, I found out about the Black Panther Party and my friend’s father took us all over to the different offices—from Newark, Jersey City, to Brooklyn and Harlem—to learn what we could do. So, we went to the political education classes and learned the terminologies; this revolution the Panthers were talking about required study, engagement in the community, and organizing. It was different from the spontaneous rebellions. It was more like the organizing when we demanded Black history; you had to have a sustained view and understand that this is a long-term struggle against the system.

Most of us who formed that chapter were high school students and active inside the high school where the rebellion took place. It was in that same area that we did most of our outreach—speaking with folks, selling the Panther paper, and at a certain point starting a storefront and a free clothing program. So, here we are, learning how to work amongst the people in this Panther style . . . Every time I look back at it, I’m like, “Oh my God, we were so young, but we were so ready!”

We had so many folks helping us learn the different things involved with carrying out revolutionary struggle. And it was great because coming out of the Black Power ideology, I didn’t have too much love for white folks. But the Panthers always remembered they’re human beings, too, and had relationships with so many different people. They were nationalists, but revolutionary nationalists and didn’t just chop white folks off because they’re white. It all depends on their practice.

So, it helped me to challenge some of my own limitations and to open up to what this new ideology was telling me about struggle, the history of struggles, the possibility of winning, believing in ourselves, and organizing from below. That carried me for a long time, even up into prison.

Helia Rasti: I was born in Tehran, Iran in 1980. That was at the start of an eight-year war between Iran and Iraq, on the heels of a revolution that ousted a dynasty, the last Shah of Iran. It was part of a popular uprising that brought in theocratic Islamists and started over four decades of Islamist rule.

I was born into a solidly middle-class family. My parents were really scared of having to raise a daughter in the growing patriarchal environment and decided to leave as did many at that time. This was very difficult for them because they loved Iran and didn’t want to go but felt forced to. We were able to attain resident status in Germany and I lived there from age five to ten. Being a foreigner in Germany is not easy and my parents (who are both well-educated) wanted access to better opportunities like they had in Iran. So, they left Germany the first chance they could and came to the United States—the “land of opportunity.”

I was ten years old when we moved to California and had no idea about the political environment and the history of oppression, genocide, enslavement, and exploitation that the US is founded on. I think a lot of immigrants come here seeking better opportunities because whatever they left behind was so grim. And then you come here and you’re like, “whoa.” Even though I was raised with this backdrop of intense political activity and very strong anti-imperialist sentiments, I was clueless. But I could just tell this is not right. Something is not right.

I’ve always been sensitive and empathic. And I knew that despite being an immigrant, being a brown child who experienced racism, I could still always seek out love and support from my parents. But I remember encountering figures about how every five minutes a girl or a woman is raped, and feeling, “Wow, I’ve been really protected.” So, I felt it was important for me to step up for people who were more vulnerable and for voices that were being silenced.

I grew up in the Bay Area and, after high school, I went to Humboldt State in Northern California. I’ve always been drawn to nature. I was a biology major initially and I learned about Native American history, the exploitative nature of industrial capitalism, and that Native people are still around and have been resisting genocide and erasure for all these years. I also learned about different resistance movements by listening to lecture series like Michael Parenti who broke down imperialism and Marxism, US foreign policy, and how the CIA and the United States played a huge part in destroying the fabric of different cultures. And, in my country, how they stood against democratic movements to support regimes to access resources for more global power.

I was sitting with all that in the late 90s when the anti-WTO, anti-corporate, globalization movements emerged. I was on the periphery of this, but learning. And then September 11th happened, and I was just like this is it. Ward Churchill wrote this essay about the chicken coming home to roost and I was feeling, “Oh, of course, this is going to come back to us to us. The United States is going to reap the repercussions of its global policies.” I got on the phone with my mom all excited about this and she said, “What are you saying? You’re going to get in trouble, you’re Iranian!” But I still felt these were historic times and decided that I had to leave the forest. I realize now it was a spiritual journey that led me to take on political action. It was my love for life, for the earth, for people. This is what kept me seeking out different answers when faced with the contradictions that are presented to us in society . . . So, I came home to the Bay as I realized my work was there and transferred to San Francisco State.

Within the first week of school there were student organizations tabling, including a Students for Peace group that did gorilla theater. I got in and became really involved with them. At the time we were organizing these huge demonstrations against the bombing of Afghanistan, and it was already clear that they were gearing up to start invading Iraq. I was a part of this mass movement; hundreds of thousands of people, millions of people globally, crying out against war.

That became my world. I spent all my time at school organizing and eventually dropped all my classes because that’s the only thing that mattered to me. I then became a part of this woman’s center that was helping to open up space for coalition building. San Francisco State has a very radical history, but since the time of the sixties and seventies, the administration has built all these guards and policies against student activism. So, we were organizing this coalition, bringing together different organizations like Ethnic Studies, the Black Student Union, and different cultural groups. We were also doing that with City College.

Eventually I dropped out of school and started doing organizing work full-time. I got involved with the Not in Our Name movement and Direct Action to Stop the War, focusing on street blockades and holding war profiteers accountable by going to them and shutting down their operations. I was especially jiving with these queer anarcho-punx doing public blockades and shutdowns. And it was like the work became my life. It’s the thing that kept me going. It felt like, this is what I was brought here for.

So, I continued to seek to deepen my understanding of what the work really was. And it was Critical Resistance that really helped to do so, especially with learning about abolition and how prison industrial abolition was a way to build against the state. At the time, I was doing environmental justice work, focusing on shutting down power plants. But I continued to encounter contradictions within organizing communities and felt I needed to do something else. I needed to figure out what my role was and not necessarily as a public or professional organizer. Again, I was always driven by my spirituality and my love. Rose Braz was a mentor of mine—what an immense, powerful woman and organizer she is—and I sought her out about some of these contradictions. And she said, “You know, you feel called to heal and you’re doing this medicine work; we need more abolitionists, more radicals to do that work. If you feel like that’s where life is taking you, go for it!” So, I did. I left the Bay and came to Portland to study natural medicine. Now I’m licensed as a clinician. But my love is still very much for the earth, for people, and dismantling obstacles to our collective liberation to allow for our ability to just live.

P M-G: You both have decades of political consciousness and organizing experience. Retrospectively, what are your biggest takeaways? What lessons have you learned that you’d want to pass on to someone just getting involved in social change work?

AA: I’ve been around for a while and when I’m speaking with young folks, I want to make sure I’m giving the best advice and encouragement that I can because I still believe that we can change this world. The thing is, you want to make sure, no matter what you have been through—the ups, the downs, the things that work, things that didn’t work—to be as honest as you can about it. When I look back on the early years—the Black Power movement to the Panthers, even up to the prison experience—then I get to see, “Oh, we could have been better in this area or that area.” The time I spent in prison was a lot of that looking back period for me. Before that it was 24/7 revolutionary work . . . not a lot of time for reflection.

But now I’m there in prison and thinking about what happened: “Why am I here? Why are so many of the comrades now in prison?” I wanted to know where we went wrong, why we lost, why the counter-intelligence program was eventually successful, and how to avoid making the mistakes again. And I got access to other readings. You know, in my head I’m still this Panther. A Marxist-Leninist. Maoist even. But the Critical Theory crew, from Eric Fromm to Herbert Marcuse and others; they had some different analysis about these revolutionary struggles that wasn’t the canon of Stalin. Then I started reading not only the critical theory, but other radicals. And, at some point, little bits and pieces of the anarchism started getting in there. These different perspectives allowed me to really think about the way we saw this struggle. What we (the Panthers) had believed was revolutionary in a sense, but with some limitations. It wasn’t great how we saw the struggles of women; it wasn’t great how we saw internalized oppression . . . Our own behaviors also contributed to our downfall. A lot of people don’t want to hear that, especially your comrades. But if you want to win, then you’ve got to let that ego shit go and say, “Where else might we have done better?” And that’s where the critical theories and anarchism and radical feminism began to help me to see things differently.

So, I want young people to understand revolution from a very personal perspective. How is it really going to impact you? What is it really opening you up to? Like, who’s Ashanti as a part of this? I’m still a part of this heterosexist, evil society and it’s been a part of my peoples’ struggle for the last 400 years. There’s no way that I can deny that. The shit of this system is also a part of me. In this struggle, it’s on two fronts; it’s not only the larger system, but also what it looks like inside of us. I want young people to see what their own connection is to this system is and to see their possibilities.

The best thing that really helped me to see this was when I started reading about anarchism. Now, not only do I want to be the best anti-sexist, but I want to open myself up to how life expresses itself. I joke about it at times when I say that when I first came out of prison I wanted to work with Love and Rage folks, but they had these spiked hair styles and I was like, “What the fuck is this?” But another part of me wanted to learn; “I don’t care how crazy they look. I want to learn.” And it showed me that there’s all kinds of folks who are oppressed by this society and who want out from under that oppression. If their lives don’t match mine, that’s okay.

The Zapatistas have that idea, too; a world where many worlds exist. Our lives are very diverse, and we all want our liberation. We just have to figure out how it’s going to work in this monstrous, US imperialist empire. So, Black folks’ struggle takes on particular characteristics, but it’s not divorced from all the other struggles—the Chicanos, the Indigenous folks, the Puerto Rican independence movement, the workers, the environmentalist movement, Palestine. It’s never simple, but it’s doable.

H.R.: I’d say never stop questioning; question your questions. Get with mentors, but also make sure that your mentors hold space for questioning and grapple with those questions with you. Recognize that you are a part of something immense. The Earth is all about life and death is a part of it, right? You are a part of something so much greater and when you take steps towards that collective health and life and love, you’re bringing with you something so much deeper. Trust that. The ongoing genocides around the world, that’s real. But the little steps that you are a part of, the little acts of kindness and love and the ways that you are showing up in support of community and life. That’s real, too. Movements are about cultivating and nourishing life as steps towards collective liberation. That is a part of that picture, too. It’s important to have this perspective that goes back and forth between the local and the global. So, continue to get involved, but don’t lose sight of your own care and holding that deep sacred space within you to stay in alignment with the goodness of life.

P M-G: Where should those of us who are dedicated to transforming society be putting our energies? And what role do you see collective care and nurturance playing in sustaining radical social movements?

H.R: We can’t be human without our connection to other humans. We’re social creatures. We’re part of a community of life that’s not just human. So, understanding your role in terms of community within that greater scheme of life, of ecological life, is important. And building these connections is so important because industrial culture has severed our connection to nature. But nature is what makes us human. We learn what it means to be human by learning from the earth. That’s something I’ve learned from Indigenous movements, writers, and activists.

It’s hard because we internalize oppression, which can be a toxin that is spread through community. And yet, community is an extended family and an extended circle of love. So, you can choose how to build community and how to engage with it. If it weren’t for my communal ties with the people who have come before me who I’m still connecting with, who inspire me, I wouldn’t be here. They keep me going. It’s hard though, and I know for me, sometimes I need to retreat in times to find my connection and to continue to show up. I need to have good boundaries and some guard up. We need to have collectively permeable boundaries. There’s a difference between having a wall, which is a tool of war, versus boundaries, which are important and healthy for life. Finding that balance is essential, especially now in a time of pandemics. I see the coronavirus as an expression of an ecological crisis. We’re going to continue to see viral storms take shape and we need to understand this balance.

A.A.: People in this struggle need to understand that this is long term. You have to have a place within you that you go to with all that you’re going to experience being in this struggle. Because it’s tough.

I just came back from an indigenous retreat in Texas at a sweat lodge that’s women led. I watched the process of building that lodge and what became so important for me was how everything they did had purpose and intentionality. This helps us to see all that is sacred. There are some important lessons in there, whether you’re Marxist, an anarchist, or just a rebel who wants change. This is still Turtle Island to Indigenous folks. And I think our objective is really to figure out how to pry this empire off the back of the Turtle so that we can all be fucking free!

What we went through back in the sixties and seventies, we got too scientific, and we missed out some things that are really about our humanity. A lot of the revolutions we put on a pedestal for being successful—like the Russian Revolution, the Cuban Revolution—but they end up recreating some other form of oppressive society. Part of anarchism for me is to be open. So, we have to figure out how to nurture the spiritual as a source of power in this struggle. It reminds me of in the days of the People’s Revolutionary Constitutional Convention that the Panthers held in Philly in 1970, with the idea of bringing all these movements together within the Empire. To see how we can all be free.

P M-G: What advice would you give about how we should relate to each other and accept differences of opinion without condemning each other? How do we nurture a community, while engaging in collective self-care and transformation?

H.R.: Allow principles to guide our work and have space for accountability. I know I’m not going to get along with everybody and I don’t need to work closely with everybody. I don’t need to know what the nitty-gritty of that work is. If the larger structure is being maintained and bringing us together in unity and if everyone is acting in ways that are principled and towards a shared mission, I can trust that. We’re all super different and that’s a beautiful thing. We’re not always going to get along and that’s a part of the friction and tension. But we can create a lot of forward momentum from that if it’s being guided by something that is principled and shared.

A.A.: We have to figure it out as we go, but a thing that has always attracted me to anarchism—is that part about how we are with each other. This is so key to the vision we have for the world that we want. If we don’t want a sexist world, we have to practice anti-sexism within our relations. If we don’t want an ageist or ableist world, we have to practice it now . . . When we come together now, we have to practice it, and be willing to admit we make mistakes when we practice this. It doesn’t just change automatically. And this takes compassion. When we begin to accept each other with compassion, this will be easier. Then we will learn to transform these relationships.

Young folks need to know not only how to organize in the community, but how they can change themselves and have better relationships with each other, which is part of community care. That’s why transformative practices need to be incorporated into what we do. It can’t just be you got an ideology now and you think that’s it for you. Now you are the revolutionary that can change the world. No, don’t work that way. It takes courage to be vulnerable, to say, “Yo, I need some help working through my shit ‘cuz that Empire is in me . . . so we can really build authentic revolutionary relationships that can transform the world.”

But the younger generation, they want to do better than what we did. And the level of solidarity we’re seeing in Gen Z’s pro-Palestinian support, anti-genocide is blowing my mind. I can’t remember this level of solidarity even with the anti-Vietnam War. I get a sense that they want to figure out ways how to be better with each other as they’re doing their work.

P M-G: I want to get into a little bit about what y’all think about the state of radical movements today. There’s the genocide in Gaza, there’s a major election coming up in this country . . . It’s a time of change around the world. What should we be paying attention to and doing?

A.A.: Part of my concern is security state; the state of surveillance, the continuous growth of the prison industrial complex. I think those things are still closing in on us, to the point where they have the ability to know so much about what we’re doing that it limits possibilities. But the spirit of the people is greater than man’s technology. This system is constantly trying to control the possibilities of insurrection and rebellion. We’ve still got to make this happen, but with a sense of urgency because they are determined to keep this empire going for as long as they can.

H.R.: I think it’s important to do that spiritual work and recognize that we’re all connected, intertwined. It can be really easy to project onto other people tendencies you might not like about yourself. That’s why doing that shadow work is so important. Also, globally, xenophobia is a way we separate ourselves from others and say, “Oh, but I’m not like that. My ways are better.” Getting past that illusion of superiority is important. None of us have the answer. There’s hope and uncertainty and we need to go where we’ve never been. It’s scary, but on the flip side there’s a sense of awe and mystery.

I think it’s also important to focus on infrastructure, both socially and physically. Socially, I mean, in terms of all the systems of domination that keep us in place and force us into submission with the prison industrial complex and State apparatus. I think the prison industrial complex is an expression of social infrastructure. Then there’s also the physical infrastructure and how it’s being destroyed by the neoliberal scheme to divest from it. Everything is literally falling apart. But there’s also a shift that’s taking place that’s allowing us to hone in on what really matters—how we can create systems that bring us closer together to collectively build cohesion and new infrastructure that is in line with serving life as a whole. I see people playing more with ideas around ecology. That’s what de-growth is; it’s about actually shifting the economy to value life and recognition that we don’t need to continue growing, but need to grow inward, downward, back to the earth, into society and community. That makes me feel hopeful.

We should be focusing on the Earth and climate catastrophe, while creating more points of connection because things are going to continue to unravel. The Earth is going to continue to try to shock us into making some real global changes. And that doesn’t all have to be bad. If we have systems in place that enable us to take care of each other—like mutual aid—that will allow us to pull together resources locally as things start to unravel and have better plans in place. So, connect with the people who are thinking about those things, arming and strengthening themselves with the knowledge that allows us to build out of the chaos. Do that shadow work, connect with your own source energy, and trust that it’s connected to the goodness of love and life that you were born into. Move from that place. And don’t lose heart!

A.A.: We used to talk about temporary autonomous zones. That can be any time you take a moment with other people to talk with each other and interact in ways that helps you to reconnect. Just as human beings and with the earth. You’ve got to realize that you’re not just an independent activist. In this thing here, you are connected to all that that is; from history to the future or as the Indigenous folks say, “the next seven generations.” When we talk about changing the world it’s not just the oppressive structures in the name of some revolutionary rhetoric. The change is within. We are a part of shaping culture. And culture, as a practice, is changeable. It’s always changing and that’s a beautiful thing.