Scientists named 190 new plants and fungi species in 2025 – including gruesome spider-killing fungus

By Liam Gilliver

Published on 08/01/2026 - EURONEWS

Almost 200 newplants and fungi were named new to science last year, with conservationists warning that many are already “threatened with extinction”.

Today (8 January), the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (RBG) in London, along with its international partners, has revealed its top 10 species that were described in 2025. The list aims to highlight just how much of the natural world still remains unnamed.

“Describing new plant and fungal species is essential at a time when the impacts of biodiversity loss and climate change accelerate before our eyes,” says Dr Martin Cheek, senior research leader in RGB Kew’s Africa team.“It is difficult to protect what we do not know, understand and have a scientific name for.”

Dr Cheek adds that wherever his team looked, human activities are “eroding nature to the point of extinction”. He argues that failing to invest in taxonomy (aka classifying species), we risk dismantling the very systems that “sustain our life on Earth”.

Telipogon cruentilabrum is a new species of orchid found in the high Andean forests of Cotopaxi in Ecuador. Named after the bloodstained lip of the flower, the species grows on tree daisies, typically around 1.5 to 3 metres above the ground.

Its yellow and red-veined flowers mimic female flies to attract sexually aroused males for pollination. However, more than half of this species’ habitat has already been cleared, and tree felling continues due to mining and agriculture.

RBG says there are only around 250 known species of Telipohon in the world, with this particular species being one of four new plants described in 2025.

“They are notoriously difficult to cultivate, and species can only be identified when in flower,” the organisation adds.

‘Grusome’ spider-killing fungus

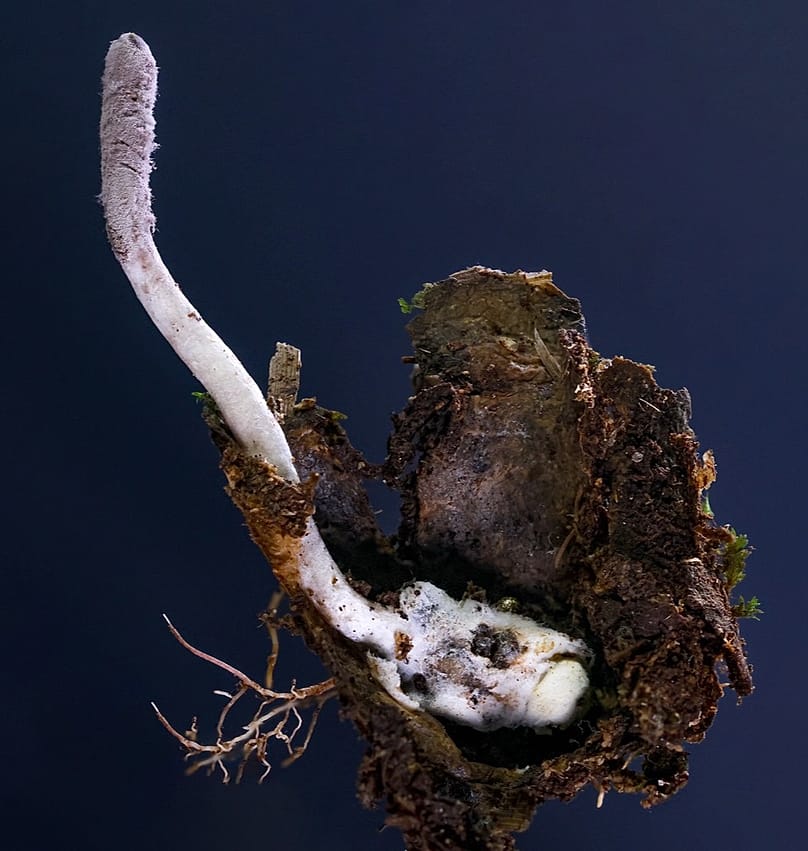

The newest member of the fungal kingdom may send a shiver down your spine. Purpureocillium atlanticum, found in the Atlantic rainforest of Brazil, belongs to a group of entomopathogenic fungi that parasites other organisms.

Otherwise known as zombie fungus, this creepy species infects trapdoor spiders buried in the forest floor inside their burrows, covering the spider almost completely with a soft mycelium.

From the corpse, a fruiting body emerges, passes through the trapdoor hole and is held above the ground to release its spores and continue the cycle.

The fire demon flower

Instantly recognisable by its bright orange-red and yellow flowers, this three-metre-tall forest shrub was named after Calcifer, the fire demon from the 2004 film Howl’s Moving Castle.

Scientists think the Aphelandra calciferi has great potential as a conservatory ornamental plant thanks to its striking appearance.

It is one of two new species from Peru published in a paper by the Peruvian-UK author team of Villanueva-Espinoza and John Wood, an honorary research fellow on Kew’s Americas team.

Christmas palm

Known locally as Amuring, this stunning red-fruited palm tree grows up to 15 metres tall. Now scientifically recognised as Adonidia zibabaoa, it grows on karst limestone ridges in a small area of typhoon-prone Samar Island, one of the Visayas of the Philippines. The species name derives from an old name for Samar.

Related

“Nature needs action, not just discussion,” says founder of IDEA international campaign

RBG says its designation as a new-to-science species was “challenging” as it was not immediately obvious what genus the tree belonged to. However, DNA analyses confirmed its placement in the genus Adonidia.

There are only two other species known in the genus, including the Christmas palm, one of the most widely cultivated tropical ornamentals in the world.

‘Living stone’

Scientifically named Lithops gracilidelineata subsp. Mopane, this species belongs to a group of plants famed for their stone-like camouflage.

While they may look like no more than a mere pebble at first glance, lithops are actually succulents with a single pair of leaves and a daisy-like flower.

The 38 known species are confined to arid regions in Namibia and South Africa, though some have also been found in Botswana. However, the new ‘mopane lithops’ differs from all others as it grows in a higher rainfall area with ‘mopane’ woodland. It also has a smooth, whitish grey leaf surface rather than cream or brownish pink.

Lithops are popular in cultivation, often as houseplants, but illegal over-collection from the wild to supply this market is driving the species towards extinction. Several species have already been categorised as Endangered or Vulnerable to Extinction by the IUCN.

A critically endangered snowdrop

This beautiful flower may look similar to the snowdrops you see scattered around the UK. However, it did not appear to match any known species as first observed by snowdrop enthusiast Ian McEnery.

Scientists have since traced its origin to the sub-alpine grasslands of Mount Korab in northern Macedonia and Kosovo. Now officially named Galanthus subalpinus, the tiny snowdrop has already been declared as Critically Endangered due to threats from collecting for the horticultural trade.

Overgrazing and fires are additional factors putting this species at risk.

Caterpillar orchid

The caterpillar orchid (Dendrobium eruciforme) gets its nickname because the tiny, creeping plants resemble a colony of caterpillars sitting on a tree trunk.

This is the smallest of six new species published by Indonesian scientists last year.

Five of the discoveries arise from Kew’s work with local partners to identify the most important areas to conserve in Indonesian New Guinea.

Fungus from grass roots

A high proportion of the fungi scientists have yet to describe are expected to be those not easily detected by the human eye. Magnaporthiopsis stipae, which was isolated from the roots of a grass last year, is a perfect example.

This is just one of 24 new species, 11 new genera and one new family published as new to science in a study of an order of fungi, which are mainly endophytes and the agents of plant diseases.

Picking fruit from this 18-metre-tall tree from Papua New Guinea is relatively easy. They are produced on stems that run down from the trunk and along the ground for up to seven metres, producing white flowers.

Scientists say the fruit tastes like a hybrid of a banana and guava, with a eucalyptus aftertaste. The species, named Eugenia venteri, is thought to have evolved to have its flowers pollinated and seeds dispersed by giant ground rats found in the area.

Detaroid legume tree

Saving the biggest until last, this endangered tree can be found in the Cameroon rainforest – with a trunk diameter of 66 centimetres. Scientists have roughly calculated that the Plagiosiphon intermedium has a mass of 5,000 kg.

It is a detarioid legume (a member of the bean family) that is the first species to be added to the Plagiosiphon genus, previously with just five species, in nearly 80 years.

Detarioid legume trees grow in groups and depend on fungi that form symbiotic relationships with tree roots. The new species is known from only two locations, both in Ngovayang, one of Cameroon’s top hotspots for unique plant species, but it is currently unprotected.