Steve McQueen and Jonathan Glazer separately confront the Holocaust with themes prompted by a resurgence of the far right

Vanessa Thorpe

|

| STEVE MCQUEEN |

Steve McQueen and Jonathan Glazer, two of Britain’s most admired and daring film directors, have disturbed Cannes audiences with a pair of extraordinary films that confront Europe’s murderous fascist past.

The directors, working independently on different projects about Nazi atrocities, both say they were prompted by the growth of political extremism and prejudice.

Glazer, best known as director of the sci-fi dystopia Under the Skin and the admired gangster film Sexy Beast, says he wants The Zone of Interest, which premiered to acclaim on Friday evening, to address “the capacity within each of us for violence”. He believes, he said this weekend, it is too easy to assume such brutal behaviour is a thing of the past.

“The great tragedy is human beings did this to other human beings,” he said. “It is very convenient to think we would never behave in this way, but we should be less certain of that.”

His unflinching look at the proximity to mass genocide in which German domestic life went on is set in the home of Auschwitz camp commandant Rudolf Höss.

McQueen’s documentary, Occupied City, also turns to historic detail to lay out the unpalatable facts that lie in the landscape of modern Amsterdam.

Speaking to the Observer in Cannes, McQueen said: “People aren’t stupid. They do realise on one level what happened, but somehow we need to smack ourselves out of this amnesia.”

The Oscar-winning director and his Dutch wife, Bianca Stigter, who wrote the script, were also prompted by the rise of the new right and Europe’s increasing political polarisation.

“The past can’t be on the surface all the time,” said Stigter, “but some things should not be forgotten. In today’s climate, with antisemitism and racism on the rise, it is good to be reminded of that moment of history.”

Both directors have turned to face Nazi horrors partly because witnesses to the Holocaust are no longer so numerous. Speaking to the press on Saturday, Glazer, who is a Jewish Londoner, said he felt it was vital to keep telling the story, despite the advice his own father gave him to just “let it rot”, and leave it to history.

“It is very important we do keep bringing it up and making it familiar; to keep showing it so that a new generation can discover it in film. The Holocaust is not a museum piece that we can have a safe distance from. It needs to be presented with a degree of urgency and alarm,” he said.

The two British films concentrate with forensic intensity on what people are capable of ignoring. While neither film portrays Nazi violence directly, both contain elements that will make difficult viewing for a mainstream audience, and not just because of their bleak focus.

Glazer’s film, made on location near the site of the former death camp in occupied Poland, is made in German. McQueen and Stitger’s documentary lasts four hours and deliberately has no narrative structure.

In each case there are few concessions to the world of popular entertainment. Glazer’s film has a lurid, deadpan mood, while McQueen’s relies on the build-up of appalling crimes recounted over footage of modern Amsterdammers going about their lives during the pandemic lockdown.

“It is about evidence of things unseen,” said McQueen. “Meandering through one of the most beautiful cities to ramble in, so there is the perversity of the fact all these things happened in such a beautiful city.

“Our film is not a history lesson, it is an experience.”

In The Zone of Interest Glazer portrays domestic life alongside the Auschwitz death camp. It has an almost surreal tone as it juxtaposes the quotidian concerns of the Höss family with the mass torture, starvation and killing going on next door. Glazer loosely based his film on the Martin Amis book and developed it after spending time at Auschwitz.

The audacity of looking at Nazi atrocities afresh has been applauded by one of Germany’s great directors, Wim Wenders.

Before watching either film, Wenders, in Cannes for the premiere of his film Perfect Days this week, told the Observer that tackling the Holocaust in film is risky, but it remains important to try.

“We should be capable of looking back at war. If we can stand the ugliness of staring it in the face and if we can then stand doing it with actors … then we can learn for the present and for the future. But it is a painful process and it can also go damn wrong.”

The monumental film which tracks day-to-day life in Amsterdam under Nazi rule asks hard questions of what we think about the gulf between past and present

Peter Bradshaw

@PeterBradshaw1

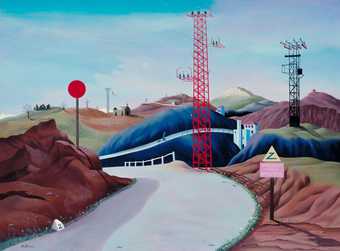

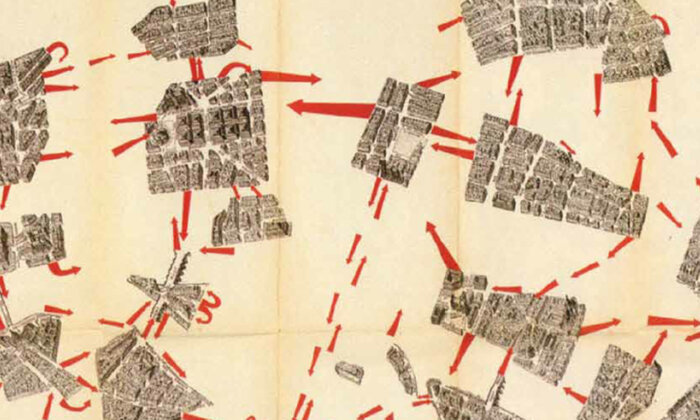

Steve McQueen’s monumental film is a vast survey-meditation on the wartime history and psychogeography of his adopted city: Amsterdam, based on his wife Bianca Stigter’s Dutch-language book Atlas of an Occupied City, Amsterdam 1940-1945.

With a calm and undemonstrative narrative voiceover from Melanie Hyams, the film tracks day-to-day life in Amsterdam under Nazi rule. It spans the invasion in 1940; the establishment of the NSB, the collaborationist Dutch Nazi party; the increasingly brutal repression and deportation of Jewish populations to the death camps; and then the “hunger winter” of 1944 to 1945 as food and fuel became scarce in the city and the Nazis displayed a gruesome mix of panic and fanaticism as the allies closed in.

What McQueen does is effectively represent the maps and figure legends of the book on screen: the camera shows us the modern-day indoor and outdoor scenes on individual streets, canals, squares, buildings and jetties where the barbarity unfolded – but shows them as they are now, with 21st-century people going about their business while Hyams’ narration coolly summarises what happened in each particular spot, sometimes adding that the original building has been “demolished”. A prison yard where Jews were forced to parade around chanting: “I am a Jew, beat me to death, it’s my own fault” is now an open space overlooked by the Hard Rock Cafe. The headquarters of the secret police was on the site of what is now a school.

Occupied City lasts a little more than four hours, with an intermission, and the effect is something like an huge cinematic frieze or tapestry, or perhaps an installation. But it is also like an old fashioned “city symphony” movie, and, in its approach, perhaps bears the influence of Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah. It asks hard questions of what we think about the gulf between past and present. When we think about Nazi rule in Amsterdam, we think of … what? Flickering black-and-white newsreel footage, semi-familiar landmarks in monochrome, images of swastikas, an alien display of history, vacuum-sealed in the past. But McQueen shows us the modern world, in 4K resolution and there is a gradual realisation that for those involved in 1940, the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam happened just like this: in living colour in the here-and-now, with modern hairstyles and clothes.

Sometimes there is a disconnect between past and present. The site of a bygone horror might in 2023 be a scene of happiness: people ice-skating on a frozen canal and having innocent fun. At some other place we see a commemorative event: the laying of wreaths. At other times, there will be a parallel: in Dam Square the Nazi occupiers erected a bandstand; now we see a stage for outdoor performance. And then there are other, serious engagements with history and politics. We see an official statement of apology for colonialism and slavery; we see a huge and boisterous “climate strike” by young people and an event for the murdered Dutch investigative journalist Peter R de Vries. The effect is to show us that the past and present are not clear, with distinct layers of old/significant and new/insignificant: it is more fluid than that.

Occasionally, there is a weird frisson. Some of McQueen’s footage was shot during the Covid lockdown and the juxtaposition of this with Nazi oppression takes us – unintentionally – perhaps a little close to GB News territory. And audiences might be surprised at how little emphasis is placed on Anne Frank: it could well be that McQueen wanted to take us away from well-trodden arguments, and certainly to move away from the modern tourist cliches of coffee shops and sex worker windows. Although on that last point there is another eerie historical echo in the way in which sexual activity between occupier and occupied was variously policed, tolerated and punished.

In its scale and seriousness, Occupied City allows its emotional implication to amass over its running time. The effect is mysterious and moving.

Occupied City screened at the Cannes film festival.