In this context, the imperialist hierarchical system based on US hegemony is openly questioned and challenged by other major powers, such as China and Russia, as well as by others on a regional scale, such as Iran. This global geopolitical competition is clearly evident in certain war conflicts, the evolution of which will determine a new configuration of the balance of power within this system, as well as of the blocks present or in formation, such as the BRICS. In light of this new scenario, in this article I will focus on a summary description of the current panorama, then characterise the different positions that appear within the left in this new phase and insist on the need to build an internationalist left that is opposed to all imperialisms (main or secondary) and in solidarity with the struggles of the attacked peoples.

Polycrisis and authoritarian neoliberalisms

There is broad consensus on the left regarding the diagnosis we can make of the global crisis that the world is currently going through, with the eco-social and climate crisis as a backdrop. A polycrisis that we can define with Pierre Rousset as “multifaceted, the result of the combination of multiple specific crises. So we are not facing a simple sum of crises, but their interaction, which multiplies their dynamics, fueling a death spiral for the human species (and for a large part of living species)” (Pastor, 2024).

A situation that is closely related to the exhaustion of the neoliberal capitalist accumulation regime that began in the mid-1970s, which, after the fall of the bloc dominated by the USSR, took a leap forward towards its expansion on a global scale. A process that led to the Great Recession that began in 2008 (aggravated by austerity policies, the consequences of the pandemic crisis and the war in Ukraine), which ended up frustrating the expectations of social advancement and political stability that the promised happy globalization had generated, mainly among significant sectors of the new middle classes.

A globalization, it must be remembered, that was expanded under the new neoliberal cycle that throughout its different phases: combative, normative and punitive (Davies, 2016), has been building a new transnational economic constitutionalism at the service of global corporate tyranny and the destruction of the structural, associative and social power of the working class. And, what is more serious, it has turned into common sense the “ market civilization” as the only possible one, although this whole process has acquired different variants and forms of political regimes, generally based on strong States immune to democratic pressure (Gill, 2022; Slobodian, 2021). A neoliberalism that, however, is today showing its inability to offer a horizon of improvement for the majority of humanity on an increasingly inhospitable planet.

We are therefore in a period, both at the state and interstate level, full of uncertainties, under a financialized, digital, extractivist and rentier capitalism that makes our lives precarious and seeks at all costs to lay the foundations for a new stage of growth with an increasingly active role of the States at its service. To do so, it resorts to new forms of political domination functional to this project that, increasingly, tend to come into conflict not only with freedoms and rights won after long popular struggles, but also with liberal democracy. In this way, an increasingly authoritarian neoliberalism is spreading, not only in the South but increasingly in the North, with the threat of a “reactionary acceleration” (Castellani, 2024). A process now stimulated by a Trumpism that is becoming the master discursive framework of a rising far right, willing to constitute itself as an alternative to the crisis of global governance and the decomposition of the old political elites (Urbán, 2024; Camargo, 2024).

The imperialist hierarchical system in dispute

Within this context, succinctly explained here, we are witnessing a crisis of the imperialist hierarchical system that has predominated since the fall of the Soviet bloc, facilitated precisely by the effects generated by a process of globalization that has led to the displacement of the center of gravity of the world economy from the North Atlantic (Europe-USA) to the Pacific (USA, East and Southeast Asia).

Indeed, following the Great Recession that began in 2007-2008 and the subsequent crisis of neoliberal globalization, a new phase has begun in which a reconfiguration of the global geopolitical order is taking place, tending to be multipolar but at the same time asymmetrical, in which the United States remains the great hegemonic power (monetary, military and geopolitical), but is weakened and challenged by China, the great rising power, and Russia, as well as by other sub-imperial or secondary powers in different regions of the planet. Meanwhile, in many countries of the South, faced with the plundering of their resources, the increase in sovereign debt and popular revolts and wars of different kinds, the end of development as a goal to be achieved is giving way to reactionary populisms in the name of order and security.

Thus, global and regional geopolitical competition is being accentuated by the different competing interests, not only on the economic and technological level, but also on the military and values level, with the consequent rise of state ethno-nationalisms against presumed internal and external enemies.

However, one must not forget the high degree of economic, energy and technological interdependence that has been developing across the planet in the context of neoliberal globalisation, as was clearly highlighted both during the global pandemic crisis and the lack of an effective energy blockade against Russia despite the agreed sanctions. Added to this are two new fundamental factors: on the one hand, the current possession of nuclear weapons by major powers (there are currently four nuclear hotspots: one in the Middle East (Israel) and three in Eurasia (Ukraine, India-Pakistan and the Korean peninsula); and, on the other, the climate, energy and materials crisis (we are in overtime!), which substantially differentiate this situation from that before 1914. These factors condition the geopolitical and economic transition underway, setting limits to a deglobalisation that is probably partial and which, of course, does not promise to be happy for the great majority of humanity. At the same time, these factors also warn of the increased risk of escalation in armed conflicts in which powers with nuclear weapons are directly or indirectly involved, as is the case in Ukraine or Palestine.

This specificity of the current historical stage leads us, according to Promise Li, to consider that the relationship between the main great powers (especially if we refer to that between the USA and China) is given through an unstable balance between an “antagonistic cooperation” and a growing “inter-imperialist rivalry”. A balance that could be broken in favour of the latter, but that could also be normalised within the common search for a way out of the secular stagnation of a global capitalism in which China (Rousset, 2021) and Russia (Serfati, 2022) have now been inserted, although with very different evolutions. A process, therefore, full of contradictions, which is extensible to other powers, such as India, which are part of the BRICS, in which the governments of its member countries have not so far questioned the central role of organizations such as the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund, which remain under US hegemony (Fuentes, 2023; Toussaint, 2024).

However, it is clear that the geopolitical weakening of the United States — especially after its total fiasco in Iraq and Afghanistan and, now, the crisis of legitimacy that is being caused by its unconditional support for the genocidal State of Israel — is allowing a greater potential margin of manoeuvre on the part of different global or regional powers, in particular those with nuclear weapons. For this reason I agree with Pierre Rousset’s description:

The relative decline of the United States and the incomplete rise of China have opened up a space in which secondary powers can play a significant role, at least in their own region (Russia, Turkey, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, etc.), although the limits of the BRICS are clear. In this situation, Russia has not failed to present China with a series of faits accomplis on Europe’s eastern borders. Acting in concert, Moscow and Beijing were largely the masters of the game on the Eurasian continent. However, there was no coordination between the invasion of Ukraine and an actual attack on Taiwan (Pastor, 2024).

This, undoubtedly facilitated by the greater or lesser weight of other factors related to the polycrisis, explains the outbreak of conflicts and wars in very different parts of the planet, but in particular those that occur in three very relevant current epicentres: Ukraine, Palestine and, although for now in terms of the cold war, Taiwan.

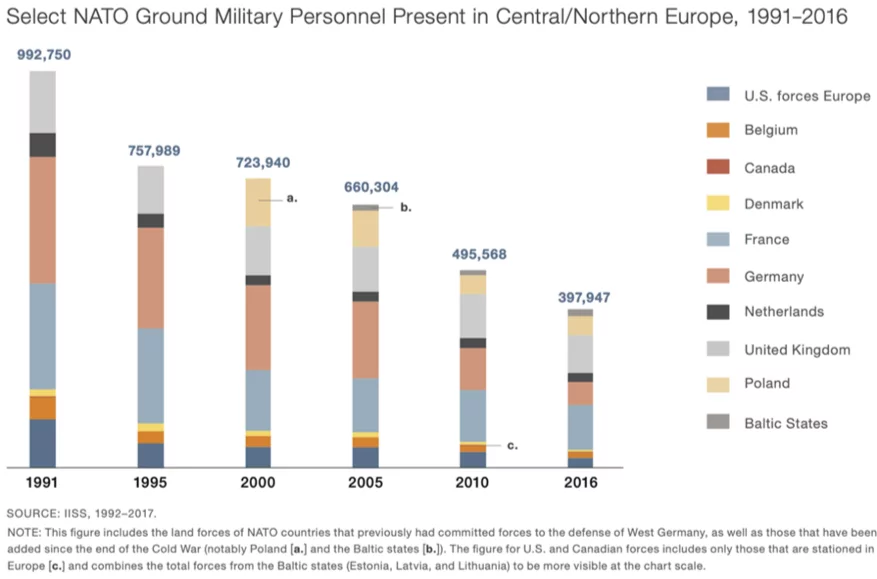

Against this backdrop, we have seen how the US took advantage of Russia’s unjust invasion of Ukraine as an excuse to relaunch the expansion of a NATO in crisis towards other countries in Eastern and Northern Europe. An objective closely associated with the reformulation of NATO’s “new strategic concept”, as we were able to see at the summit that this organisation held in Madrid in July 2022 (Pastor, 2022) and more recently at the one held in Washington in July of this year. At the latter, this strategy was reaffirmed, as well as the consideration of China as the main strategic competitor, while any criticism of the State of Israel was avoided. The latter is what is showing the double standards (Achcar, 2024) of the Western bloc with regard to its involvement in the war in Ukraine, on the one hand, and its complicity with the genocide that the colonial State of Israel is committing against the Palestinian people, on the other.

Again, we have also seen NATO’s growing interest in the Southern flank in order to pursue its racist necropolitics against illegal immigration while continuing to aspire to compete for control of basic resources in countries of the South, especially in Africa, where French and American imperialisms are losing weight against China and Russia.

In this way, the strategy of the Western bloc has been redefined, within which US hegemony has been strengthened on the military level (thanks, above all, to the Russian invasion of Ukraine) and to which a more divided European Union with its old German engine weakened is clearly subordinated. However, after Trump’s victory, the European Union seems determined to reinforce its military power in the name of the search for a false strategic autonomy, since it will continue to be linked to the framework of NATO. Meanwhile, many countries in the South are distancing themselves from this bloc, although with different interests among them, which differentiates the possible alliances that may be formed from the one that in the past characterized the Non-Aligned Movement.

In any case, it is likely that after his electoral victory, Donald Trump will make a significant shift in US foreign policy in order to implement his MAGA (Make America Great Again) project beyond the geoeconomic level (intensifying his competition with China and, although at a different level, with the EU), especially in relation to the three epicentres of conflicts mentioned above: with regard to Ukraine, by substantially reducing economic and military aid and seeking some form of agreement with Putin, at least on a ceasefire; with regard to Israel, by reinforcing his support for Netanyahu’s total war; and finally by reducing his military commitment to Taiwan.

What anti-imperialist internationalism from the left?

In this context of the rise of an authoritarian neoliberalism (in its different versions: the reactionary one of the extreme right and that of the extreme centre, mainly) and of various geopolitical conflicts, the great challenge for the left is how to reconstruct antagonistic social and political forces anchored in the working class and capable of forging an anti-imperialism and a solidarity internationalism that is not subordinated to one or another great power or regional capitalist bloc.

A task that will not be easy, because in the current phase we are witnessing deep divisions within the left in relation to the position to maintain in the face of some of the aforementioned conflicts. Trying to synthesize, with Ashley Smith (2024), we could distinguish four positions:

The first would be the one that aligns itself with the Western imperial bloc in the common defense of alleged democratic values against Russia, or with the State of Israel in its unjustifiable right to self-defense, as has been stated by a majority sector of the social-liberal left. A position that hides the true imperialist interests of that bloc, does not denounce its double standards and ignores the increasingly de-democratizing and racist drift that Western regimes are experiencing, as well as the colonial and occupying character of the Israeli State.

The second is what is often described as campism, which would align itself with states such as Russia or China, which it considers allies against US imperialism because it considers the latter to be the main enemy, ignoring the expansionist geopolitical interests of these two powers. A position that reminds us of the one that many communist parties held in the past during the Cold War in relation to the USSR, but which now becomes a caricature considering both the reactionary nature of Putin’s regime and the persistent state-bureaucratic despotism in China.

The third is that of a geopolitical reductionism , which is now reflected in the war in Ukraine, limiting itself to considering it to be only an inter-imperialist conflict. This attitude, adopted by a sector of pacifism and the left, implies denying the legitimacy of the dimension of national struggle against the occupying power that the Ukrainian resistance has, without ceasing to criticize the neoliberal and pro-Atlanticist character of the government that heads it.

Finally, there is the one that is against all imperialisms (whether major or minor) and against all double standards, showing itself ready to stand in solidarity with all attacked peoples, even if they may have the support of one or another imperial power (such as the US and the EU in relation to Ukraine) or regional power (such as Iran in relation to Hamas in Palestine). This is a position that does not accept respect for the spheres of influence that the various major powers aspire to protect or expand, and that stands in solidarity with the peoples who fight against foreign occupation and for the right to decide their future (in particular, with the leftist forces in these countries that are betting on an alternative to neoliberalism), and is not aligned with any political-military bloc.

This last position is the one that I consider to be the most coherent from an anti-capitalist left. In fact, keeping in mind the historical distance and recognizing the need to analyze the specificity of each case, it coincides with the criteria that Lenin tried to apply when analyzing the centrality that the struggle against national and colonial oppression was acquiring in the imperialist phase of the early twentieth century. This was reflected, in relation to conflicts that broke out then, in several of his articles such as, for example, in “The Socialist Revolution and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination,” written in January-February 1916, where he maintained that:

The fact that the struggle for national freedom against an imperialist power can be exploited, under certain conditions, by another ’great’ power to achieve equally imperialist ends cannot force social democracy to renounce recognizing the right of nations to self-determination, just as the repeated cases of the use of republican slogans by the bourgeoisie for the purposes of political fraud and financial plunder (for example, in Latin countries) cannot force social democrats to renounce their republicanism (Lenin, 1976).

An internationalist position that must be accompanied by mobilisation against the remilitarisation process underway by NATO and the EU, but also against that of other powers such as Russia or China. And which must commit to putting the fight for unilateral nuclear disarmament and the dissolution of military blocs back at the centre of the agenda, taking up the baton of the powerful peace movement that developed in Europe during the 1980s, with the feminist activists of Greenham Common and intellectuals such as Edward P. Thompson at the forefront. An orientation that must obviously be inserted within a global eco-socialist, feminist, anti-racist and anti-colonial project.

References

Achcar, Gilbert (2024) “Anti-fascism and the Fall of Atlantic Liberalism”, Viento Sur, 19/08/24.

Awad, Nada (2024) “International Law and Israeli Exceptionalism”, Viento Sur, 193, pp. 19-27.

Camargo, Laura (2024) Discursive Trumpism . Madrid: Verbum (in press).

Castellani, Lorenzo (2024) “With Trump, the Age of Reactionary Acceleration”, Le Grand Continent, 11/08/24.

Davies, William (2016) “Neoliberalism 3.0”, New Left Review , 101, pp. 129-143.

Fuentes, Federico (2023) “Interview with Promise Li: US-China Rivalry, ’Antagonistic Cooperation’ and Anti-Imperialism”, Viento Sur, 191, 5-18. Available in English at https://links.org.au/us-china-rivalry-antagonistic-cooperation-and-anti-imperialism-21st-century-interview-promise-li

Gill, Stephen (2002) “Globalization, Market Civilization and Disciplinary Neoliberalism”. In Hovden, E. and Keene, E. (Eds.) The Globalization of Liberalism. London: Millennium. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lenin, Vladimir (1976) “The Socialist Revolution and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination”, Selected Works, Volume V, pp. 349-363. Moscow: Progreso.

Pastor, Jaime (2022) “NATO’s New Strategic Concept. Towards a New Permanent Global War?”, Viento Sur, 07/02/22. Available in English at https://links.org.au/towards-new-permanent-global-war-natos-new-strategic-concept

— (2024) “Interview with Pierre Rousset: World Crisis and Wars: What Internationalism for the 21st Century?”, Viento Sur, 04/16/24. Available in English at https://links.org.au/global-crisis-conflict-and-war-what-internationalism-21st-century

Rousset, Pierre (2021) “China, the New Emerging Imperialism”, Viento Sur, 10/16/21.

Serfati, Claude (2022) “The Age of Imperialism Continues: Putin Proves It”, Viento Sur, 04/21/22.

Slobodian, Quinn (2021) Globalists. Madrid: Capitán Swing.

Smith, Ashley (2024) “Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism Today”, Viento Sur, 06/04/24. Available in English at https://links.org.au/imperialism-and-anti-imperialism-today

Toussaint, Eric (2024) “The BRICS Summit in Russia Offered No Alternative”, Viento Sur, 10/30/24.

Urbán, Miguel (2024) Trumpisms. Neoliberals and Authoritarians . Barcelona: Verso.

section of Germany where a Red Republic had briefly been proclaimed. Mussolini’s victory lay just ahead. The Seattle General Strike of 1919 was already slipping from memory and the Communist factions engaged mainly in fighting each other—a serious matter because the US was not only the new center of the bourgeoisie but also because a leftwing challenge to capitalism there had been counted upon by revolutionaries around the globe.

section of Germany where a Red Republic had briefly been proclaimed. Mussolini’s victory lay just ahead. The Seattle General Strike of 1919 was already slipping from memory and the Communist factions engaged mainly in fighting each other—a serious matter because the US was not only the new center of the bourgeoisie but also because a leftwing challenge to capitalism there had been counted upon by revolutionaries around the globe.