Blair McBride | March 5, 2026 |

A Kazatomprom uranium exploration site in Kazakhstan. Credit: Kazatomprom

Laramide Resources (TSX, ASX: LAM), one of the few Western companies to explore for uranium in Kazakhstan in recent years, is leaving the country as regulatory changes tighten restrictions on foreign participation.

State miner Kazatomprom (LSE: KAP) – the world’s top uranium producer – confirmed in late December the Kazakhstan government changed its Subsoil Use Code, giving the miner priority rights to exploration licences in prospective areas. Most projects must be done in joint ventures and the new law states that Kazatomprom gets at least 75% in them.

“This rule is going to keep any company from wanting to explore in Kazakhstan, not that there were a lot before either,” Red Cloud Securities analyst David Talbot told The Northern Miner by email. The changes amount to “de facto nationalization of the uranium industry in Kazakhstan,” he said.

Kazakhstan, historically integrated into the Soviet system with production largely directed to Moscow, now supplies much of the Western uranium market. Its move to strengthen state control over the sector through legal channels is a potential risk to supply that could support higher prices.

Laramide’s hopeful entry

In 2024, Laramide entered a three-year option agreement with Kazakh company Aral Resources to explore on more than 5,500 sq. km in the Chu-Sarysu Basin in southern Kazakhstan. The site is adjacent to Kazatomprom’s Inkai JV mine it holds with Canadian producer Cameco (TSX: CCO; NYSE: CCJ) and the Budenovskoye JV the state miner holds with Russia.

On Dec. 24, the Toronto-based explorer received the final permits to start drilling its 15,000-metre program. But two days later, Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed into law the Subsoil Use Code changes.

“We had three rigs ready to go, basically on standby, we had all the people ready to go, we had the targets and unfortunately we never went out and drilled anything and had to walk away,” Laramide CEO Marc Henderson told The Northern Miner in an interview. The company announced on Jan. 20 it had ended its option agreement with Aral.

Henderson had heard rumours about the legal changes for a while and he realized last fall that the “dramatic decision” was going to be enacted.

“It would be like Newmont going to the US government saying there’s a lot of gold here, why don’t you ban everyone else in Nevada except us. Except [in this case] it’s not for gold, it’s something critical that the world needs, like uranium.”

Asked to specify which part of the law spurred Laramide to leave the country, Henderson responded with a scenario where the company made a major discovery and approached Kazatomprom about its interest in a JV to potentially mine uranium.

“We thought the range that we were going to end up negotiating would be 30% to 50%,” he said. “[But] they made it law that the new terms that they had to have were between 75% and 90%. That was just a completely different deal.”

Why the amendments?

The code changes are “essential for the systematic modernization of Kazakhstan’s subsoil use regulations,” a Kazatomprom spokesperson told The Northern Miner by email.

“The revisions are intended to optimize the management of strategic resources, providing the framework necessary to reinforce Kazakhstan’s global market presence.”

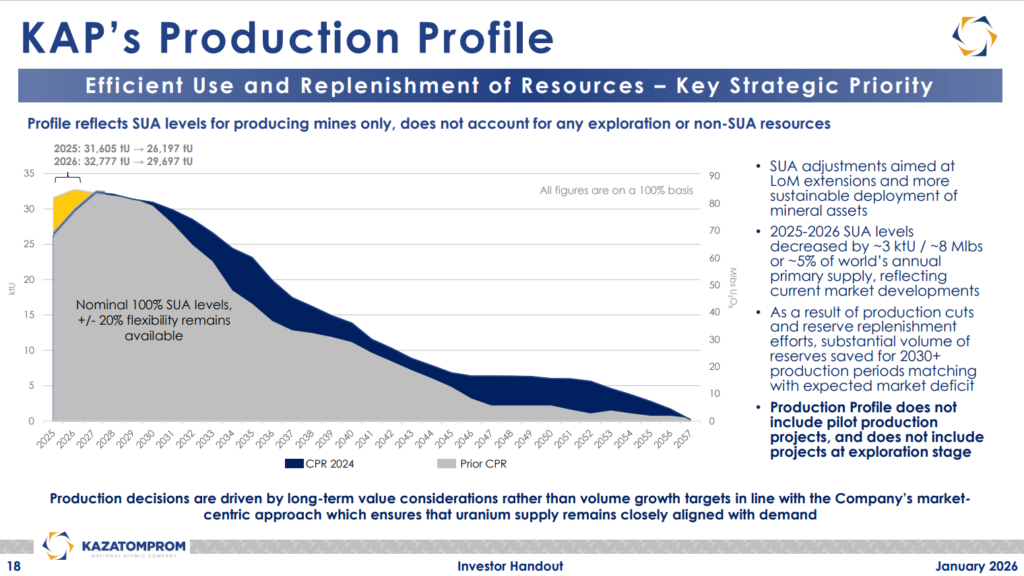

Henderson noted that Kazatomprom revealed its dwindling reserves in an investor’s presentation deck. A January deck showed that its production resource base would peak this year, then begin a rapid decline in a few years, with complete exhaustion by 2057.

Credit: Kazatomprom

Credit: KazatompromKazatomprom board chair Meirzhan Yussupov suggested as much to the Central Asia-focused Kursiv business publication in December.

The amendments are needed, Kursiv reported, as higher prices could attract higher-cost producers, reducing Kazakhstan’s advantage and depleting its reserves.

In addition, Kazakhstan’s Atomic Energy Agency said it needs the underground use amendments so it has enough fuel sources for planned nuclear power plants, according to reporting from Radio Free Europe’s Russian service on Feb. 9.

Greenfield exploration loss

Laramide incurred no costs to leave Kazakhstan and for now plans to re-focus on its projects in Australia and the southwest US.

Still, Henderson thinks it’s a loss for global greenfield uranium exploration that one of the world’s most prospective jurisdictions is now effectively closed to Western investment.

“The uranium sector is woefully behind on greenfield exploration,” he said. “The prospectivity in uranium to find things of any scale is very, very small. And not all of those are jurisdictions where you want to go on vacation, or where you’re comfortable with the politics.”

Australia’s C29 Metals (ASX: C29) is another Western company that was exploring for uranium in Kazakhstan. It acquired the Ulytau project in 2024. But C29 announced it was ending operations there in late November after regulators rejected its application for exploration rights, according to Minex Forum, a U.K.-based mining conference platform focused on Eurasian markets. C29 did not respond to a request for comment from The Northern Miner.

How will producers fare?

Western majors like Cameco, France’s Orano and Japan’s Sumitomo Corp. and Kansai Electric Power could face similarly difficult conditions in Kazakhstan.

Cameco’s contract in the Inkai JV – in which it holds a 40-60 interest with Kazatomprom – ends in 2045. Orano is in a 51-49 interest arrangement with Kazatomprom in Katco, made up of the South Tortkuduk/Muyunkum operation.

While Kazatomprom said existing subsoil use agreements are unaffected, contract extensions or production increases would require Kazatomprom to hold at least 90% of the JV. Alternatively, the foreign partner could keep its interest by transferring uranium conversion and enrichment technologies to Kazatomprom and build downstream capacity.

Of the non-Western producers in the country, seven are Kazakh, two are Russian, two are Chinese and one is Kyrgyz. Most production projects are held in JVs.

“This is part of the ongoing expectation that Kazakh uranium will be increasingly destined for eastern destinations (Russia, China), and less available to the West,” Red Cloud’s Talbot said. “It would impact the Chinese, Russians, Orano, Cameco and others – essentially reducing their interest and production.”

A Cameco spokesperson said in emailed comments to The Northern Miner that the company’s subsoil use agreement in the Inkai JV is valid until 2045 and Cameco has transferred refinery and conversion technology to its partner.

“Foreign interests requiring a new subsoil use agreement or an extension of a current agreement will face the requirement to increase state ownership,” the spokesperson said. “While the change in legislation is certainly impactful more broadly in the market, our agreement remains in place for the next 20 years.”

Pivot to East, spot prices

Talbot noted that global production as such might not be affected by Astana’s legal changes, and he expects all long-term uranium sales contracts would be intact, “but future contracts would likely be focused to an even greater extent on Chinese and perhaps Russian customers.”

In terms of the uranium spot price, which soared about 33% from late November until late January, when it peaked at $101.55 per lb., Talbot suggested Kazakhstan’s policy change could play a bullish role.

“Uncertainty surrounding uranium security of supply is often a catalyst for rising uranium price,” he said. “This could be very good for uranium prices, and potential M&A as western producers scramble for future production.”

NexGen eyes summer 2026 build for huge Rook I uranium mine

NexGen Energy (TSX, NYSE: NXE; ASX: NXG) said it will start construction this summer of its Rook uranium mine in northern Saskatchewan, the largest development-stage uranium deposit in Canada.

The C$2.2 billion capex build plan for Rook I comes on the same day the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) approved NexGen’s environmental assessment and construction licence, and just weeks after the regulator’s two-part hearing process concluded. Located in the uranium-rich Athabasca basin’s southwest, Rook I is about 900 km northwest of Regina.

“Current expectations are for a four-year construction period,” Canaccord Genuity Capital Markets analyst Katie Lachapelle said in a note on Thursday. “We expect NexGen to release a detailed construction schedule in the near-term.”

The approval follows one of the most rigorous regulatory processes conducted for a resource project in the world, NexGen CEO and founder Leigh Curyer said in a release.

“This milestone is the result of the NexGen team’s steadfast and unrelenting focus over 12 years understanding and delivering our objectives honestly and incorporating a culture of excellence,” he said.

Top uranium producer

Rook I, anchored by the high-grade Arrow deposit, could produce almost 30 million lb. of uranium oxide (U3O8) per year over the first half of its 11-year life, according to a feasibility study published in 2021.

That capacity would make it the top uranium mine by output in North America, ahead of Cameco’s (TSX: CCO; NYSE: CCJ) producing McArthur River and Cigar Lake mines in Saskatchewan.

NexGen’s construction milestone also coincides with other developments for uranium players in the province over the past several weeks.

Denison Mines (TSX: DML) last week announced the start of construction of its Phoenix mine, Canada’s first in-situ recovery operation for the nuclear fuel. Last month, Paladin Energy (TSX, ASX: PDN) received environmental impact statement approval from the Saskatchewan for its Patterson Lake South project.

All three projects would rank in the top five largest operations in the Athabasca basin by reserve size if they become producing mines.

C$6.3B value

NexGen shares fell 3% to C$16.77 apiece on Thursday afternoon in Toronto amid a broad market decline, valuing the company at C$10.1 billion ($7.4 billion).

In a uranium spot price case of $95 per lb., Rook I has a net present value (at an 8% discount) of C$6.32 billion and an internal rate of return of 45%. The Arrow deposit hosts probable reserves of 4.57 million tonnes grading 2.37% U3O8 for 240 million lb. of U3O8.

Rook I uranium project gets construction approval

_75011.jpg)

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) decision to issue the Licence to Prepare Site and Construct the proposed uranium mine and mill came 14 business days after the conclusion of the last part of the regulator's two-part hearing process. The licence - which is valid until 31 March 2036 - covers site preparation and construction activities under Canada's Nuclear Safety and Control Act: operation of the facility would need NexGen to submit another licence application which would be subject to a future licensing hearing and decision.

Rook I is described by NexGen as the largest development-stage uranium project in Canada. Centred on the Arrow deposit, a high-grade uranium deposit discovered by the company in 2014, the project is in the southern Athabasca Basin, about 155 km north of the town of La Loche. The project is situated on Treaty 8 territory, the Homeland of the Métis, and is within territories of the Denesųłiné, Cree, and Métis.

The Arrow deposit has a resource estimate of 357 million pounds U3O8 (137,319 tU) in the measured and indicated mineral resources category, grading 3.10% U3O8. Probable mineral reserves have been estimated at 240 million pounds U3O8, grading 2.37% U3O8. A 2021 NI 43-101 feasibility study for the project envisages production of up to 14 million kilograms of U3O8 annually for 24 years.

The project received environmental approval from the Province of Saskatchewan in November 2023, and, with all approvals now secured, NexGen said it is set to begin construction. A final investment decision has already been made, and the team, procurement, engineering, vendors, contractors and capital are in place to commence construction activities with advanced site and shaft sinking preparation. Construction will officially begin in this summer, the company said, and construction is expected to take four years to complete.

NexGen founder and CEO Leigh Curyer said the CNSC's approval "represents one of the most rigorous and comprehensive regulatory processes undertaken for a resource project globally" and, as well as acknowledging NexGen's team, expressed the company's "sincere gratitude" to its Indigenous Nation partners, local communities, Premier Scott Moe and the Government of Saskatchewan, Government partners, regulatory bodies, and stakeholders who have contributed to the advancement of the project over the past decade.

"The world is changing fast, and NexGen's Rook I is now ready to be a significant contributor to global requirements for nuclear energy and Canada's role as an energy superpower. As global demand for reliable, clean, baseload nuclear energy continues to accelerate at an unprecedented pace, uranium is the critical fuel for powering industrial electrification and the digital infrastructure of tomorrow. Simply put, energy is the key to our global growth," Curyer said.

In February, Reuters reported that NexGen had held preliminary talks with data centre providers about securing finance for a new mine. Speaking to investors in NexGen's fourth quarter conference call on 4 March - one day before the CNSC announcement - Curyer said the first 12 months of construction is expected to cost around CAD300 million (USD219 million). NexGen is well funded to begin construction thanks to already completed equity raises and offtake agreements. Further offtake agreements are already in advanced negotiation, with contracts expected to be announced this year, he said, but the start of construction or production will not be dependent on those new contracts being in place.

"We know exactly what we're doing every day of that 48-month process, who's doing it, who's responsible for it within NextGen," Curyer said. "And as I said, once we're in that basement rock, the highest risk around cost and schedule has been mitigated."

Curyer told investors the company would issue a detailed construction timeline once the licensing process had concluded.

Canada and India Sign Landmark Uranium Deal Worth $2.6B

- Canada is expanding trade with India as Prime Minister Mark Carney seeks to reduce reliance on the U.S. after 2025 tariffs, aiming to double non-U.S. exports within a decade.

- Major energy and commodities deals were signed, including a 10-year uranium supply agreement between Cameco and India.

- Canada and India are pursuing deeper economic ties, with plans for a free-trade agreement targeting $70B in bilateral trade.

Ever since Donald Trump slapped tariffs on Canadian goods on Feb. 1, 2025, Prime Minister Mark Carney has been encouraging trade with nations other than the United States.

The former central banker turned politician wants to double non-US exports over the next decade.

Towards that goal, Carney met with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Delhi on Monday as part of a four-day trip to deepen trade and diplomatic ties.

The centerpiece was a deal between the Indian government and Saskatchewan-based uranium producer Cameco (TSX:CCO) to supply nearly 22 million pounds of uranium for nuclear energy generation between 2027 and 2035.

Also, British Columbia coal producer Elk Valley Resources — majority-owned by Glencore (LSE:GLEN) — will sell 1.2 million tonnes of coal to India worth hundreds of millions of dollars. (CBC News)

As reported by the National Post newspaper,

Emerging from a set of meetings with India Prime Minister Narendra Modi earlier in the day, Carney announced that a new $2.6-billion agreement had been struck between India and Saskatchewan that will see the Prairie province supply it with uranium, which India needs for nuclear power generation.

The 10-year deal, set to begin in 2027, is part of what the Prime Minister’s Office calls a new “strategic energy partnership,” which was one of the outcomes expected out of Canada’s renewed interest in working with India.

The uranium contract with Saskatoon-based Cameco was one of the 10 commercial deals, some of which were years and months old, that Carney’s office said totalled around of $5.5 billion that he touted as signs of a deepened relationship.

Many of them have to do with Canadian companies expanding into India and vice-versa.

The two leaders also announced plans for a new free-trade deal, where the goal is to double two-way trade to $70 billion over the next four years. Carney has appointed a chief negotiator and said he wants to see the agreement happen by the end of the year.Related: Trump’s Secret Weapon in the Rare Earth War

To that end, Carney’s office outlined how Canada and India signed five memorandums of understanding to commit to working towards deeper collaborations, with at least two dealing specifically with the areas of critical minerals and “diversifying supply chains.”

Carney has faced criticism at home for courting the Indian government, including inviting Modi to the G7 leaders’ summit in Alberta last year. During Carney’s trip to Delhi, Modi accepted an invitation to visit Canada. The Prime Minister’s Office reports that Canada and India have interacted more this year than in any of the last 20 years.

The diplomatic U-turn is welcome news to the Canadian business community, which likes the certainty of trade agreements.

Relations under former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau plummeted after he accused the Indian government of orchestrating violent crimes in Canada such as the killing of a prominent Sikh activist in 2023.

Some Indian diplomats were expelled from Canada, but India has denied any involvement in his death.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police subsequently alleged India was behind incidents of extortion, mainly in BC, Alberta and Ontario.

Along with uranium and coal, Carney also touted current and upcoming LNG projects in British Columbia that could help meet India’s expected doubling of population by 2040.

Related: Magnet Wars: How the U.S. Plans to Break China’s Grip on Rare Earths

“Canada is well-positioned to contribute, as a reliable supplier of the world’s lowest-carbon, responsibly produced LNG (liquefied natural gas) from our West Coast,” he said in his remarks, via CTV News.

The trade news on India came the same day that the Canadian government announced it has secured 30 new critical mineral partnerships, unlocking $12.1 billion in mining project capital.

Made at the 2026 Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) annual convention in Toronto, the announcement is the second round of partnerships and investments under the Critical Minerals Production Alliance. The first round was announced in October 2025.

The Canadian Press reported that Deals include up to $7 million to Greenland Resources' Malmbjerg project in Greenland, $9.1 million to Cyclic Materials Inc.'s rare earths elements recycling centre in Kingston, Ont. and $16.7 million for First Phosphate's Bégin-Lamarche demonstration and feasibility project in Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean, Que.

By Andrew Topf for Oilprice.com