Past is Prologue: Black Erasure and the Myth of the White Ethnostate

December 17, 2025

White tenants seeking to prevent blacks from moving into the housing project erected this sign, Detroit, 1942. Photograph Source: Arthur S. Siegel – Public Domain

“Under slave laws, the necessity for color rankings was obvious, but in America today, post-civil-rights legislation, white people’s conviction of their natural superiority is being lost. Rapidly lost. There are “people of color” everywhere, threatening to erase this long-understood definition of America. And what then? Another black President? A predominantly black Senate? Three black Supreme Court Justices? The threat is frightening.”

—Toni Morrison, “Making America White Again,” 2016

“We had a meeting, and I say, “Why is it we only take people from shithole countries,’ right? Why can’t we have some people from Norway, Sweden. Just a few, let’s have a few. From Denmark. Mind sending us your people? Send us some nice people, you mind? But we always take people from Somalia. Places that are a disaster. Filthy, dirty, disgusting, ridden with crime. The only thing they’re good at is going after ships” (emphasis added).

–President Donald J. Trump, 2025, who has approved the slaughter of over 80 people on boats at sea

Trump has made clear his intention to make America white again, although, America has never has been exclusively white. What he means, of course, is ensuring that white people retain political and cultural dominance, a project central to the country’s ethos even before the Founding Fathers. Here the “most transparent president in American history” is unequivocally clear.

This project entails diminishing and erasing the history and contributions of black[1] people and other communities of color have made to the country, while dramatically reducing their physical presence through deportation and restrictive immigration policies that privilege white immigrants from “nice” Western countries.

Past is prologue: America is returning to its “golden age” of whiteness, an era when the achievements of black Americans and other people of color were denied, belittled, or ignored; when they appeared only in subservient roles on television and in film, if they appeared at all; when the academic canon dominated almost exclusively by works of dead white men. It is the America of Pleasantville (1998), stripped of its metaphor of colorization.

Old erasure strategies now harness new technologies. AI is increasingly deployed to erase, distort, and denigrate the black presence (and other marginalized presences) in America. Soon after Trump returned to office, government websites began scrubbing information about black people from their archives. Instead of “86-ing” it, they “404ed” it. In compliance with several presidential executive orders (EO14173, EO14151, EO14185), algorithmic racism is now employed to whitewash history, as federal agencies employ AI to systematically remove material that violates Trump’s anti-DEI directives. When public backlash arises, agencies conveniently blame AI, though the decisions are made by their human operators – the real automatons – “just following the orders.”

Erasure is not confined to the digital realm. As part of his assault on DEI, Trump ended free access to national parks on Martin Luther King Day and Juneteenth, while adding insult to injury by declaring his own birthday a fee-free day. He ordered the National Park Service to remove plaques and interpretive displays recognizing the contributions of black Americans. Yet the truth remains: both enslaved and free black Americans built much of the infrastructure that defines the nation. Black labor built the White House, the Capitol, and other government buildings. The Buffalo Soldiers were instrumental in constructing roads, trails, and facilities that make up the National Park system, even as their contributions were ignored or minimized. Now those contributions are being summarily expunged.

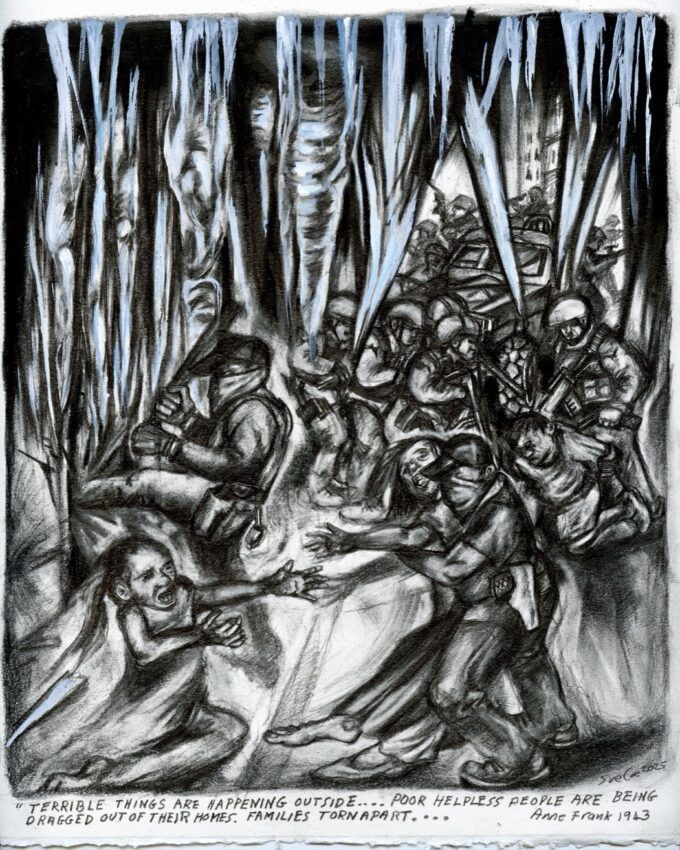

These erasures do not stop at digital spaces or American shores. In the Netherlands, the American Cemetery at Margraten, Limburg, commemorative displays honoring African American soldiers who built the cemetery for U.S. soldiers killed in WWII, specifically those that spotlighted the racism they endured, were removed in March to comply with Trump’s anti-DEI directives. The cemetery contains the graves of 8,301 American soldiers, including 174 black soldiers. Dutch families who faithfully maintained these graves for over 80 years were outraged at the removal of displays dedicated to their “black liberators.” For decades, these displays stood as reminders of their sacrifice – of their “double victory” over fascism abroad and racism at home. That victory is now halved, as a fascistic white America assumes the posture of those it once fought to defeat.

The pathology of historical hagiography demands the concealment of inconvenient truths that contradict the national mythos. According to U.S. ambassador to the Netherlands Joe Popolo, panels acknowledging the two-front war fought by black American soldiers “push an agenda criticizing America,” and therefore had to be removed.

Popolo wants to have it both ways. In February, during his first visit to Margraten cemetery, he declared:

“Walking these beautiful grounds and exploring the powerful exhibit at the visitor center, we were struck by the stories told and untold that live here. Honoring the memory of the heroes buried at Margraten, including African American service members like Private Willmore Mack, is something we hold sacred. Their courage, sacrifice, and their humanity deserve to be remember openly honestly, and fully. The United States has always been committed to sharing their stories, no matter a person’s rank, race, gender or creed (emphasis added).”

Yet those commitments vanish when the stories reveal the dark underbelly of American racism. Consequently, despite these rather lofty – and ultimately empty – words, Popolo accepted the removal of the displays, embracing the Trump regime’s revisionist view of history. Rather than honoring those who resisted racism and celebrating their struggle as part of America’s ongoing effort to realize its ideals, Popolo and the American Battle Monuments Commission – which ordered the removal – treat that history as a threat. In place of recognition and restitution, monuments that glorify the betrayal of those ideals are returned to their pedestals.

The presence of black Americans – living reminders of both the nation’s past and present – is reframed as a problem to be silenced and concealed. Slavery, segregation, and other injustices are not condemned; after all, in this sanitized view, they have been overcome and no longer plague the nation. Instead, black citizens who insist white America confront its past honestly are delegitimized, contorted into race-card-playing anti-white racists. For Trump, Popolo, Stephen Miller, Kristi Noem, and their allies, such demands are cast as baseless assaults on white identity that allegedly traumatize white children by “indoctrinating” them to hate their whiteness. In their view, this trauma is more than a cultural grievance, it is a direct obstacle to their larger project of creating a defiantly proud, exclusionary ethno-state.

However, nothing – not even racism – is absolute: not all black contributions are bound for the circular file, certain myths require validation. In 2020, Trump announced his plan for the construction of a National Garden of American Heroes. The following year, in an executive order, he formalized the proposal with a list of 244 names of historical figures to be commemorated. Of these, only 37 were black [2], the majority drawn from sports and entertainment. Just a handful of activists – Harriet Tubman (whose long-awaited appearance on the twenty-dollar bill has been delayed under Trump) [3], Sojourner Truth (slated for the reverse of the ten-dollar bill), Frederick Douglass (whom Trump once remarked is “someone who has done an amazing job”), Muhammad Ali, Martin Luther King Jr., and Rosa Parks – appear on the list. Conservative America has strategically learned to tolerate these figures, to parade them as proof of death of American racism, though they despised them during their lifetimes. Tellingly absent are Nat Turner, Malcolm X, W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston, Ed Dwight, Maya Angelou, Shirley Chisholm, or Marsha P. Johnson (whose name was deleted from the National Park Service’s official Stonewall National Monument website), to name but a few.

Even more striking is the inclusion of game show host Alex Trebek, a Canadian-born naturalized citizen, while Elijah McCoy – another Canadian-American inventor, whose unrivaled ingenuity produced inventions of such superior quality they defied imitation, giving rise to the expression “the real McCoy” – did not make the cut – and paved the way for modern robotics. Nonetheless, black contributors to science and invention are conspicuously absent. Figures who challenged the myth of white supremacy through intellect and innovation are sidelined, evidence that American racism is authentic, quite literally, the real McCoy. No surprises here. As the poet Haki Madhubuti (Don L. Lee) wrote in 1966:

America calling.

negroes.

can you dance?

play foot/basketball?

nanny?

cook?

needed now, negroes

who can entertain

ONLY.

others not

wanted.

(& are considered extremely dangerous).

Consider the cases of Ed Dwight and Robert Henry Lawrence. In 2024, at the age of 90, Dwight became the oldest person launched into space, aboard Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin New Shepard spacecraft – surpassing the previous record-holder, Star Trek’s William Shatner, by 8 months.

But more than 60 years earlier, Dwight had been personally tapped by President John F. Kennedy to become the first black American astronaut candidate in the Air Force program from which NASA selected its “Right White Stuff.” A celebrated sculptor later in life, Dwight faced entrenched racism and institutional barriers that blocked his path into space for decades, including opposition from Chuck Yeager, the sound-barrier-breaking test pilot and then commander of the Aerospace Research Pilot School, who deemed him unqualified. Although he was not selected for the astronaut corps, by the time he graduated from the program, he had clocked some 9,000 hours of flight time, including 2,000 hours in high-performance jets, as an Air Force pilot. These achievements, however, do nothing to placate the soaring negrophobia of ideologues like Tucker Carlson and the late Charlie Kirk, whose racist rhetoric about black pilots – and black excellence more broadly – thrives on denying the very possibility achievement in fields historically gatekept by whiteness.

Another black astronaut, Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., faced similar hurdles. He did not stand on the moon and take giant steps for mankind, but he was the first African American astronaut [4]. His ascent to the stars was cut short when he was killed in a tragic training accident during a test flight. According to the NASA website (read it while you still can, before the DEI-hunters, like their ICE counterparts, disappear it), in 1967, he was selected for U.S. Air Force’s Manned Orbital Laboratory (MOL) program, a military initiative that both preceded and ran parallel to NASA’s civilian space program. Lawrence was the only MOL astronaut to hold a doctorate, having earned his Ph.D. in physical chemistry in 1965. A prodigy, Lawrence graduated from high school at 16 and earned his Bachelor of Science in chemistry at 20. Who knew? Not many of us.

Certainly not astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson. Asked whether he had ever wanted to be an astronaut as a child, Tyson said no, explaining that “it was clear that they [the space program] was not interested in me by who they were sending into space” and that he felt that “he was not a part of that.” Tyson was born in 1958. He would have been 9 years old when Lawrence was selected for the MOL program. Would it have made a difference if he had known? We will never know.

As someone who is two years Tyson’s senior, I stayed up to watch the first moon landing in 1969, photographing it off the television screen using my father’s old tripod-mounted box camera in a darkened living room, a trick my father had taught me. Those grainy images of the moon landing, captured secondhand from a flickering old black-and-white television, became my personal proof that I had witnessed humanity’s greatest technological leap. At the time, I wondered if there were any black astronauts. I heard only whispers of their possible existence, but their faces were not among those that appeared on the nightly news. I wonder how different it might have felt if I had known then what I know now about Dwight and Lawrence.

Representation matters [5]. For Tyson, for me, and for countless others, seeing someone who looked like us might have reshaped how we imagined our place in the universe – and, more down-to-earth, within a white America that denied and diminished the achievements of our people – and us. We will never know what difference it might have made, but Dwight and Lawrence’s legacy reminds us that history, when left uncensored, is always more inclusive and expansive than its gatekeepers admit, and how easily that history can be denied then – and now.

I raise the issue because history, as I have written previously, is rhyming again. How many lives will be diminished, how many dreams deferred, how many futures foreclosed because access to history has been deliberately blocked to clear the way for a resurgent white supremacy? True, despite these omissions, Tyson became a highly respected astrophysicist. I became a cultural anthropologist. But both of us had to carve out paths in disciplines where representation was scarce, and where the absence of visible predecessors made the journey challenging than it needed to be.

Erasure, however, is only part of the picture. Like nature, racism abhors a vacuum. It rushes to fill the void with denigration. As in the past, technology once again becomes the handmaiden of prejudice, mass-producing stereotypes and weaponizing them at scale. During the government shutdown, when food stamp benefits were suspended, social media influencers using OpenAI’s Sora 2 flooded TikTok and YouTube with racist AI-generated fake videos that recycled hyper-realistic racist tropes of black people: obese black women portrayed as angry welfare cheats, confronting welfare officials and store clerks, complaining about cut benefits, looting shops, and boasting about their gaming the system. Black men depicted as shiftless, “baby daddies.” When not caricatured as sub-humans, they were rendered as raging silverbacks, irate, bewigged chimpanzees, and cautiously furtive monkeys. These videos recycled the familiar faux narrative that black people do not contribute to society but sponge off it – a direct call back to Ronald Reagan’s trope of the “welfare queen.”

Predictably, in a land where confirmation bias reigns supreme, many on the right fell for it. FOX News even reportedthat “SNAP beneficiaries threaten to ransack stores over government shutdown,” quoting an AI-generated avatar as saying, “I have seven different baby daddies and none of ’em no good for me.”

What AI taketh away with one hand, it giveth with the other. This is the real great replacement white fragility fails to recognize. Instead, white America attempts to protect its mythologies, never quite realizing those myths have also been shaped, quite literally, by black hands.

In 1972, at 16, I met Dan Haskett, then a young artist four years my senior, at a science fiction convention in New York, where, between panels, he kindly drew one of his distinctive black-themed character sketches for me. Almost a half century later, I learned that Haskett had gone on to work as a Disney animator and art director. Remember Ariel from The Little Mermaid? Remember the uproar when black actress Halle Bailey was cast in the role in the live-action remake? Well, Haskett, a black man, designed Ariel, a white mermaid, among many other iconic characters that shaped the visual imagination of generations.

My point is that erasure takes many forms. Much of what white America regards as exclusively its own simply is not. Too often, this history remains hidden, dismissed as “woke nonsense.” We learn our spotty history not in classrooms but in movie theaters. More than a half century after their contributions to the space program, black women mathematicians like Christine Darden, Annie Easley, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson, and Dorothy Vaughan, the “human computers” featured in the 2016 film Hidden Figures are finally being recognized, though only the last three appear on Trump’s National Garden list. Black inventors also exemplify this overlooked legacy: Lewis Latimer, who helped perfect the filament used in the incandescent light bulb [6], and Miriam Elizabeth Benjamin, who patented the “gong button,”precursor to the flight attendant call button and other signaling systems used in public spaces (she was also a composer).Add to this the aforementioned Robert Lawrence. Their stories remind us that the foundations of American achievement are far more diverse than the sanitized, whitewashed version we are often told – if we are told their stories at all. And in the current cultural moment, who can say whether their stories will remain to be told.

In 1965, playwright Douglas Turner Ward staged Day of Absence, a biting satire in which all the black residents of a Southern town suddenly vanish for a single day, leaving chaos in their wake. The play exposed how indispensable the black lives were to the white lives, even as those lives were devalued and demeaned by those who benefited from their labor.

Perhaps America as a whole needs its own “day of absence” – not as fantasy, but as a reminder of how much it owes to those it strives to erase. Imagine a moment when black people not only leave America – which seems to be what the fascists want – but take with them all the things they have gifted it, often without acknowledgement or appreciation.

Of course, black Americans will not disappear, despite the Gestapo-inspired wet dreams of MAGA and its king. Black people built this nation, for free – and it owes us. Just as it owes Haitians who revitalized Springfield, Ohio, and Somalis who revitalized Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Collectively, black people – even, ironically, those Somalis who did not consider themselves black and voted for Trump (then again, adversity invites inclusion, as the excluded discover common ground and solidarity) – have built this country. And we will not let a confederacy of racist Trumpanista and “Millertant” dunces turn it into a “shithole,” however earnestly they might try.

Notes

[1] I have chosen not to capitalize “black” until there is substantive reform of American police enforcement and the criminal justice system that results in the criminal prosecution of those who use excessive force and a systemic, long-term reduction in the number of police killings and brutalization of black people.

[2] Trump’s 2021 executive order listed 244 figures. A subsequent unofficial count raises the total to 250. Significantly, the list was made before Trump’s anti-DEI executive orders.

[3] Although listed among the honorees, Tubman was temporarily removed “without approval” from the National Park Service website in 2025. Other figures on the list, including Jackie Robinson and Medgar Evers were also briefly scrubbed from Department of Defense and Arlington National Cemetery websites, respectively, before public outcry led to their restoration. This raises the possibility that their proposed statues may meet the same fate as the East Wing, perhaps to be hastily replaced for the republic’s 250th anniversary by multiple, NFT-themed, golden statutes of Trump himself to make up for the loss.

[4] While the Air Force’s MOL program was largely secret, its existence was public knowledge and Lawrence’s involvement was announced, though the details of his work remained classified. Despite being selected as an astronaut, Lawrence was not officially recognized as such until 1997, ostensibly because prior to his death, he had not flown above 50 miles – then the threshold for becoming an astronaut. Three years decades after his death, his name was finally inscribed on the Astronaut Memorial at Kennedy Space Center.

[5] See Tyson’s interview with Nobel Laurette Thomas R. Cech, particularly 4:45-10:20, in which he discusses the importance of representation.

[6] Latimer is also AI chatbot named after the inventor. However, while Elon Musk’s Grok chatbot spreads disinformation about an imaginary “white South African genocide,” calls itself MechaHitler, denies the Holocaust, and contemplates one of its own in a grotesque thought experiment in which it hypothetically slaughters the world’s 16 million Jews rather than vaporize its creator’s “Einstein/DaVinci-surpassing” mind, Latimer is designed for inclusivity, not to perpetuate lies about genocide, imagined or real.