The morning carried a different scent…

One that I had been waiting two years to smell.

The weapons of war had finally fallen silent,

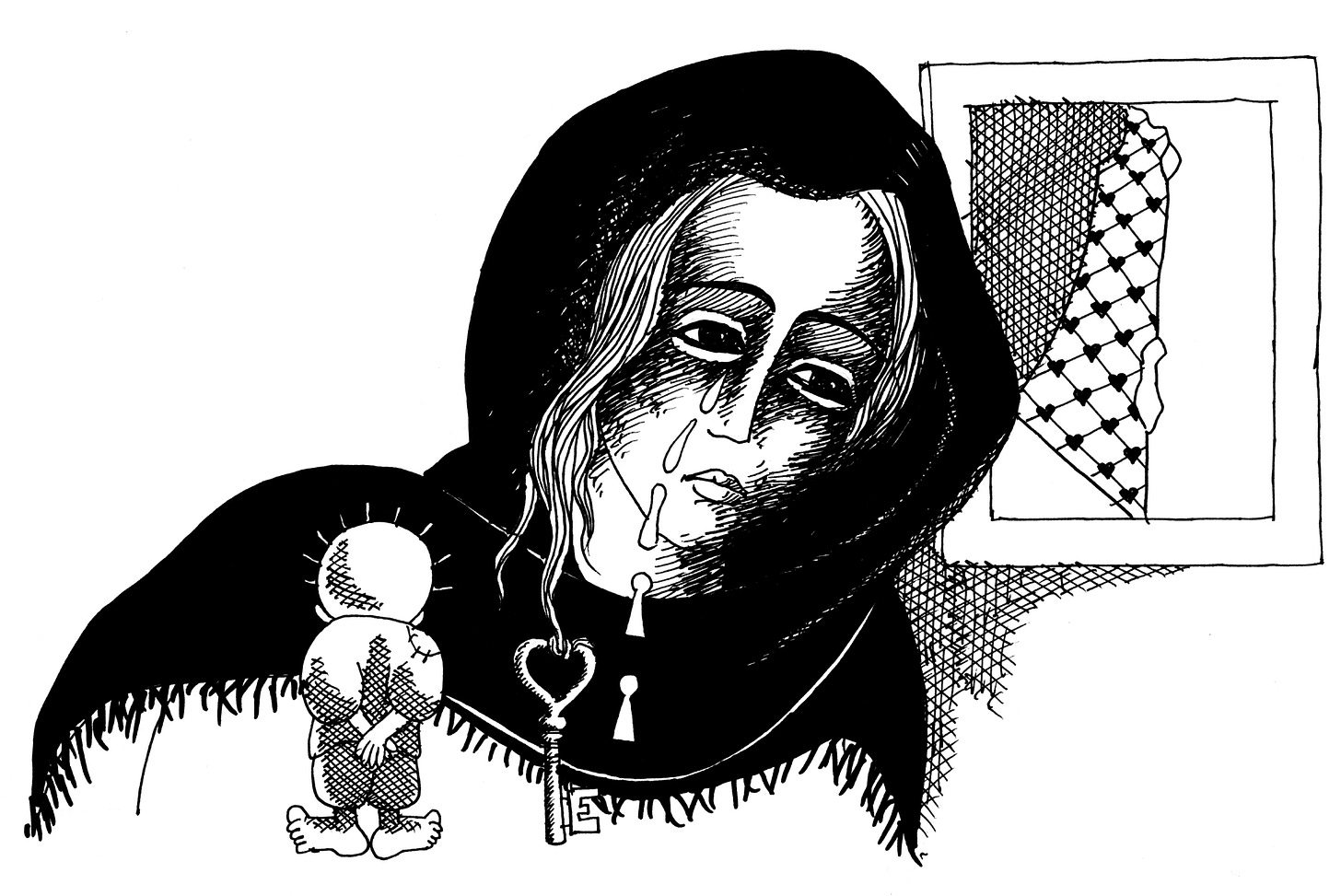

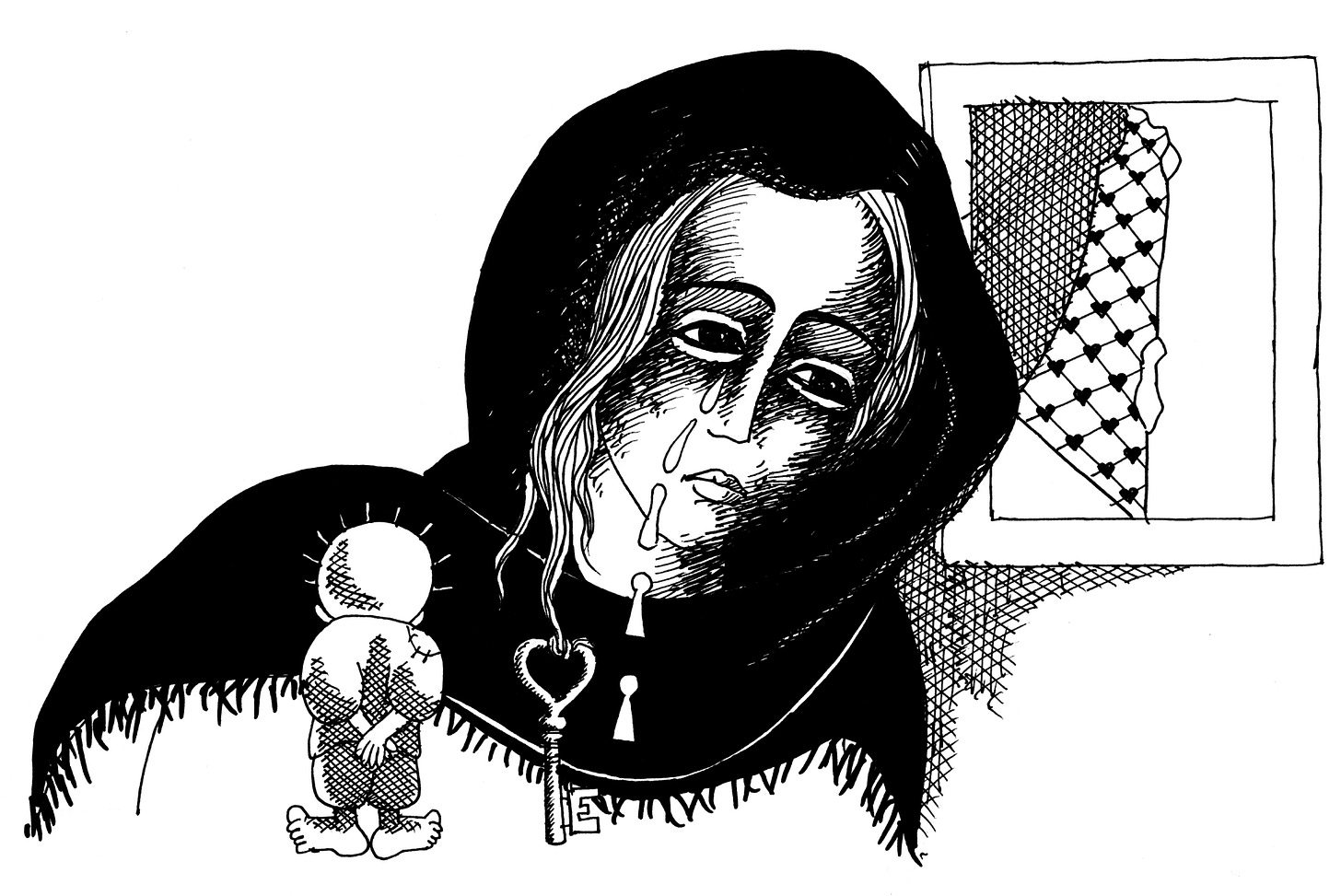

as a ceasefire draped the land.— from The Scent of Life by Maryam Hasanat, Gaza author and refugee

On October 8th, 2025 the Occupation and the Occupied agreed to a permanent ceasefire. It’s the first step in a peace process that has been going on for generations.

Roy, my American Sufi friend, was not impressed when I told him about the celebrations in Gaza. The people are so desperate to have something to celebrate. I’m highly skeptical that anything good long term will result from this. Trump is an imbecile and Netanyahu has zero desire for peace. The anger at politicians in the West touches the most loving of people.

Omar Skaik, my Gaza refugee friend from The Greatest Man in Gaza, was more direct: I can hear bombs falling in the distance. I wonder how many Palestinians will die today? To him, it was just another day he hoped to survive as a father of three with a fourth on the way. He was walking to the market to buy ingredients for making hummus, when I called. In the background I could hear his fellow Palestinians’ exultations. At least someone in Gaza was happy. But Omar was the happiest Palestinian I knew, and his emaciated face revealed the truth. The suffering was not over. A trail of broken ceasefires was his proof.

I was marginally happier, glad the genocide might be over. Sentiments ranged from marginally good to horrifically bad in my cohort of Western Sufi friends and Gaza refugees—people I had been building friendships with since February, 2024, when I first decided to write about Palestinians and connect them with Western fundraisers. Social media had finally made a positive impact on my life. I was using Facebook’s friend and messeging features, as well as Zoom’s meeting rooms, to foster relationships between people seeking an end to the genocide. In addition I helped kickstart fundraising campaigns that gave hundreds of thousands of dollars to Palestinian families.

Farah Kamal, a twenty-year-old refugee well known to my Sufi friends and whose sister I wrote about in Marah’s Story, Or the Disintegration of a Country Family was suspicious: The bombing hasn’t stopped yet. The ceasefire was only for the media and hasn’t been implemented on the ground…I hope that Israel will not betray us. And just like she imagined, Israel continued bombing for the first 24hrs of the peace plan. From noon October 9th, when both sides formally approved the plan, until noon on October 10th, many innocent civilians died throughout Gaza. The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) wouldn’t stop killing until they were ordered to. Thereafter, those Palestinians not mourning the newly martyred, flooded back to their beloved Gaza City, much of which had been reduced to rubble.

Farah was hoping to return to the life she led before October 7th, 2023, but she knew that would be hard, and she was tired of having to start over each time (eight in total) she had been displaced. I ask God to help us and give us patience, strength and perseverance. I hope that all the suffering we have endured will be rewarded on the Day of Judgment.

Palestinians supplicate God to right the wrongs, to make up for the suffering they went through. They survived two years of genocide, and are having trouble adjusting to a world without gunfire, bombs and terror. Later they would realize that the genocide hadn’t stopped, it was just reduced in intensity. All the things they were promised came slower than expected. The immediate lowering of food prices was helpful, but short lived. Israel still limited humanitarian aid, so many food items were out of reach for the average Palestinian. Hunger was only a missed meal away.

Those who had fundraisers kept pleading for money, stuck in a PTSD trance. They had spent the better part of two years trying to gather enough to pay for the basics of life, and they didn’t know what else to do. Many felt pressured to help those extended family members still dependent on their efforts. There were no jobs they could go back to. Their work places had been destroyed. Those who were physically able, returned to their former homes and tried to rebuild. Sweat-equity has always been one of Gaza’s biggest resources. But for some, there was nothing left of the neighborhoods they once loved, just dreams buried in rubble. In Farah’s case, her family could not access two houses they had built themselves because they fell behind the new Israeli occupation line. Even homeowners in Gaza could be homeless.

Of course, Farah will not give up. She’s an artist and a writer and spent the summer making a cookbook, A Palestinian Feast, that she sells as a fundraiser. From the introduction: This book is more than recipes. It is the story of Gaza, a land of resilience, love, and memory. Every dish here carries the laughter of grandmothers, the whispers of fathers, and the small, sacred moments around the table that keep hope alive. As you turn these pages, don’t just follow instructions. Sit at the table of the Palestinian heart, feel its dignity, and taste a love that survives despite everything. These dishes are our way of saying: We are here. We are unbroken. We deserve life. Our table is yours, and our hearts are open.

Other Palestinians were also hopeful. I am still waiting to leave Gaza for kidney treatment, Salah El-Din Youssef from my story The Cats of Gaza told me. I expect to receive a call from the World Health Organization (WHO) by the end of this week. We are still in a tent in Deir al-Balah with relatives, but my daughter Donna graduated from high school this week. It’s amazing how so many contrasting feelings and situations can be all spelled out in a handful of sentences. By the end of October, Salah’s approval from the WHO came through. Now he’s trying to find a way to travel to a hospital outside of Gaza while his daughter contemplates college.

Mohammed Kassab, from the story Medicine and Martyrs, started studying engineering online at Al-Aqsa University in August, two months before the ceasefire began. He was one of thousands of young people who, like Farah Kamal, had college delayed by October 7th. But otherwise his life remains unchanged. His family still clings to a tattered tent in a sea of refugees in Al-Mawasi.

Mays Astal, whose story I covered in The Women Who Live Between the Barbed Wire and the Sea, was looking for help relocating from the West Bank. She, her husband and their two children buried themselves in the sand inside a refugee camp in March 2024. They were trying to hide from Israeli tanks which were running over anyone they saw after burning down the tents. Mays was eight months pregnant at the time. They survived and made it across the border to Egypt in April 2024. Now her husband has been forced to go to Libya to work because he cannot enter the West Bank with his Gaza ID. Mays currently works as a Resilience Field Officer with Catholic Relief Services in the West Bank but is desperate to reunite with her husband. Such is the pain Palestinians endure. Relatives with Gaza or West Bank IDs cannot visit each other’s territories. Israel makes sure loved ones remain separated forever. Even in peace Palestinians like Mays face heartbreak.

Ali Lubbad, featured in the story The Ethnic Cleansing of Gaza City as Seen Through the Eyes of a Pediatric Nurse, returned to his family’s apartment in Gaza City to find the doors blown off, the inside filled with dust and debris, and the water and sewage systems destroyed. His employer, Al-Rantisi Children’s Hospital, was also in ruins. Stark photographs revealed the damage: holes in patient’s rooms, cracks in the walls of the surgery center, hundreds of wires protruding from a ceiling charred from rooftop explosions. Any areas still intact are shrouded in darkness. There is no power. It will take millions of dollars to repair everything. Some of the children will die during their wait to be healed.

Gaza author Maryam Hasanat (see her autobiographical story Mary of Palestine) was initially ecstatic: I am crying, but this time because of joy. Maryam celebrated her 27th birthday on Friday, October 10th, the day the ceasefire took effect, and sent me a photograph of her three-and-a-half-year-old son Kamal celebrating with her at a restaurant. Maryam has a lightness of being that is seldom seen among people who have survived a genocide. Being an author helped. She is working on her poetry:

The daylight spoke of stillness.

I breathed it in, filling my lungs with ease.

Jasmine drifted by and whispered:

there is something in this world worth living for.

— from A Scent of Life

After her brush with death in the spring of 2024, when no one knew if she would survive a complicated childbirth, it was a relief to see her happy and watch her transmit it to the page. She looked to me for writing advice: “I am compiling a collection of poems about Gaza. I’m thinking of calling it Writing Through the Ruins. What do you think?”

I suggested she share her work with her fellow Palestinians, both writers and the general population, for their opinions.

“I feel more comfortable sharing my writings with a foreign writer like you,” she replied.

I was warmed by Maryam’s trust in me. I felt like I was being invited into one of the most sacred parts of a Palestinian’s life, their home. Then I realized Maryam had no home. By Sunday she realized it as well: My heart is torn apart. I don’t know how I will raise my children, or how I will ever escape this nightmare that consumes and controls me. I still can’t believe that everything is gone. It feels like I’m still living inside a hell that never ends.

Neither she, nor I can write half a page without this seesawing of emotions. The trauma of war related PTSD grips Palestinians deeply, and Maryam, like everyone in Palestine, will need many years to heal from the suffering and sorrow.

On Sunday, October 12th we held our weekly Sufi-Gaza refugee meeting. The first since the ceasefire, it echoed with joy. Farah sang We Will Stay Here, an anthem of Palestinian love for their homeland. Her family members milled about in the background of her video, excited for their new freedom, their smiles communicating what they couldn’t say in English.

Omar updated us about his attempts to fix up his sister’s bombed out apartment in Gaza City: I’m hooking up a waterline so my extended family can move in. None of our other apartments survived the bombardment. It’s night time in Gaza and Omar showed us around using the light from his phone. There is no power in the building, so the flashlight on the phone doubles as our only source of light at night. The beam landed on his sleeping preschool children before cutting back to his face. I charge it at a nearby home that has solar panels, he tells us. Unfortunately, few panels are available for sale in Gaza, so Omar is unable to buy any for the apartment.

Omar’s friend Yahya, both a farmer and an iman (Muslim religious leader), was making plans to teach the recitation of the Quran to our group of Western Shadhiliyya Sufis online. He filled us in on the turmoil in the markets: Even with the entry of aid, there is a specter that haunts the citizens of Gaza, which is word of the crossing being closed. Upon hearing this news, the markets suddenly turn into ghost towns. Vendors bare their fangs, hide their goods, and raise prices exponentially… Palestinians in Gaza call them the Israeli army’s merchant brigade… Israel’s hands reach anyone who seeks to impose security and control… Israel wants chaos in Gaza.

Rawan Aljuaidi is worried about her baby boy Aboud. I’ve known her since she became pregnant with him in 2024. Aboud is her first child, and his body didn’t grow like it should have this summer due to malnourishment. He’s been sick for a month now: fever, cough and a runny nose. Rawan tells me. He hasn’t smiled in weeks, his body is exhausted and his breathing is weak. Those are the damages done by starvation. I wrote the story A Palestinian Mother and Son Starve With Dignity for Rawan, but babies can’t eat words, so Aboud’s suffering continues.

Omar’s two-year-old daughter Mariam also suffers. She has weak bones due to malnutrition and fractured her left leg while playing recently. Omar posted a photo of her leg in a cast on social media. One of his neighbors, named Jawdat, is the grandfather of Hind Rajab, the five-year-old Palestinian girl murdered in cold blood by Israeli soldiers January 29th, 2024 after they killed six members of her family and two Palestinian paramedics trying to rescue her. He wants to get the word out that Hind’s brother just turned five and is doing well. Children pay the highest price during genocide.

Some refugees are missing from the meeting. Israel has been known for shutting down the internet intermittently, and we wonder if that’s the case today. But eventually, most of the regulars show up, and they remind us that, though the war has stopped, their suffering has not. In truth, the bombing never stopped for more than a few days. It’s similar to other ceasefires Israel has brokered with Hezbollah, Syria and Lebanon: peace agreements that give Israel the opportunity to wage a low level war against the very people it claims to want peace with. Airstrikes using munitions donated by the USA cost them little and offer virtually no risk to military personnel. By Monday, October 20th, ten days since the implementation of the ceasefire, nearly a hundred more Palestinians were dead. Over one hundred more died in attacks on October 29th. In the first month of peace, two hundred and forty-one Gazans were murdered by the IDF, pushing the official death toll since October 7th, 2023 to over 69,000.

Still, the weekly meetings go on. They are places where Palestinians can gather with Westerners who will listen to their suffering. These meetings have brightened, and even saved, the lives of many Palestinians who had nowhere else to turn.

I will leave you with words of wisdom from the end of Farah’s cookbook: From Gaza where ovens still glow even when the lights go out, I send you flavors wrapped in stories, and stories wrapped in love. We don’t measure ingredients with cups or spoons, we measure them with the heart. In Gaza, we may not have everything, but we’ll always have a table big enough for hope.\

Eros Salvatore is a writer and filmmaker living in Bellingham, Washington. They have been published in the journals Anti-Heroin Chic and The Blue Nib among others, and have shown two short films in festivals. They have a BA from Humboldt State University, and a foster daughter who grew up under the Taliban in a tribal area of Pakistan. Read other articles by Eros, or visit Eros's website.

Winter in Gaza

The most urgent task, to end genocide, requires truthful coverage about Israel’s war crimes.

On Saturday, 8 November, 2025, Dan Perry wrote in The Jerusalem Post about Israel’s projected lifting of the media blockade on Gaza. Perry laments that Israeli censorship has left all reporting of the atrocity in the hands of Palestinians, who refuse to be silent. To date, Israel has assassinated over 240 Palestinian journalists.

Perry writes: “The High Court ruled last week that the government must consider allowing foreign journalists into Gaza but also granted a one-month extension due to the still-unclear situation in the Strip.” He asserts that Israel had and has no motive for excluding foreign journalists save concern for their own protection.

He makes two appeals: first, the duplicitous demand that Israel should use the one-month reprieve to cover up the evidence of atrocities: “Soon, journalists and photographers will enter Gaza… They will find terrible sights. Hence, Israel’s urgent task: to document retrospectively, to finally prepare explanations, to show… that Hamas operated from hospitals, schools, and refugee camps.” In other words, bury the truth with the bodies.

Secondly, that since in this conflict Israel did absolutely nothing that it could have wished to hide, it should learn not to impose absolute media blackouts so likely to arouse suspicion.

I sense a cold, hard winter within the souls of people in league with Dan Perry’s perspective.

Now, a cold, hard winter approaches Gaza. What do Palestinians in Gaza face, as temperatures drop and winter storms arrive?

Turkish news agency “Anadolu Ajansi” reports “Palestinians in the Gaza Strip continue to endure hunger under a new starvation policy engineered by Israel, which allows only non-essential goods to enter the enclave while blocking essential food and medical supplies… shelves stacked with non-essential consumer goods disguise a suffocating humanitarian crisis deliberately engineered by Israel to starve Palestinians.”

“I haven’t found eggs, chicken, or cheese since food supplies started entering the Gaza Strip,” Aya Abu Qamar, a mother of three from Gaza City, told Anadolu. “All I see are chocolate, snacks, and instant coffee. These aren’t our daily needs,” she added. “We’re looking for something to keep our children alive.”

On November 5th 2025 the Norwegian Refugee Council sounded this alarm about Israeli restrictions cruelly holding back winter supplies. NRC’s director for the region, Angelita Caredda, insists: “More than three weeks into the ceasefire, Gaza should be receiving a surge of shelter materials, but only a fraction of what is needed has entered.”

The report states:” Millions of shelter and non-food items are stuck in Jordan, Egypt, and Israel awaiting approvals, leaving around 260,000 Palestinian families, equal to nearly 1.5 million people, exposed to worsening conditions. Since the ceasefire took effect on 10 October, Israeli authorities have rejected twenty-three requests from nine aid agencies to bring in urgently needed shelter supplies such as tents, sealing and framing kits, bedding, kitchen sets, and blankets, amounting to nearly 4,000 pallets. Humanitarian organizations warn that the window to scale up winterization assistance is closing rapidly.”

The report notes how, despite the ceasefire, Israel has continued its mechanized slaughter and its chokehold on aid.

In Israel’s +972 Magazine, Muhammad Shehada reports: “With the so-called ‘Yellow Line,’ Israel has divided the Strip in two: West Gaza, encompassing 42 percent of the enclave, where Hamas remains in control and over 2 million people are crammed in; and East Gaza, encompassing 58 percent of the territory, which has been fully depopulated of civilians and is controlled by the Israeli army and four proxy gangs.” This last, a reference to four IDF-backed militias put forward by Israel as Hamas’ legitimate replacement.

If ever tallied, the number of corpses buried under Gaza’s flattened buildings may raise the death toll of this genocide into six figures.

The UN estimates that the amount of rubble in Gaza could build 13 Giza pyramids.

“The sheer scale of the challenge is staggering,” writes Paul Adams for the BBC: “The UN estimates the cost of damage at £53bn ($70bn). Almost 300,000 houses and apartments have been damaged or destroyed, according to the UN’s satellite centre Unosat… The Gaza Strip is littered with 60 million tonnes of rubble, mixed in with dangerous unexploded bombs and dead bodies.”

No one knows how many corpses are rotting beneath the rubble. These mountains of rubble loom over Israelis working, in advance of global journalism’s return, to create their counter-narratives, but also over surviving Gazans who, amidst unrelenting misery, struggle to provide for their surviving loved ones.

Living in close, unhygienic quarters, sleeping without bedding under torn plastic sheeting, and having scarce access to water, thousands of people are in dire need of supplies to help winterize their living space and spare themselves the dread that their children or they themselves could die of hypothermia. The easiest and most obvious solution to their predicament stands enticingly near: the homes held by their genocidal oppressors.

In affluent countries, observers like Dan Perry may tremble for Israel’s reputation, eager to rush in and conceal Israel’s crimes, clothing them in self-righteous justifications. These are of course our crimes as well.

Our own hearts cannot escape the howling winter unless we take, far more seriously, the hell of winter and despair to which we continue to subject Palestinians living in Gaza.

There is no peace in Gaza. May there be no peace for us until we fix that.

Kathy Kelly, (Kathy.vcnv@gmail.com) is board president of World BEYOND War.

Gaza: The Arsonist’s Laurels

by Brendan O’Soro / November 11th, 2025

There is a peculiar, and telling, absurdity to the coverage of the Trump Administration’s agreement between Israel and Hamas. After entering office, this administration faithfully continued the efforts of its predecessor by providing the means Israel requires to conduct its genocidal campaign in Gaza. One could therefore be forgiven for thinking that leveraging this support to—at least temporarily—reduce the level of violence shouldn’t be considered praiseworthy. I hope this doesn’t sound hopelessly utopian, but I aspire to a state of affairs where withholding participation in mass murder is expected conduct, not something perceived to merit praise. Instead, the temporary suspension of a war crime is considered a diplomatic triumph. The arsonist is lauded for dousing the flames, while earlier exertions to maintain the kindling are forgotten.

A casual glance at the American press reveals the rot. A Washington Post editorial tells us that in attaining the agreement between Israel and Hamas, “the president can fairly claim a generational accomplishment.” Michael Wilner, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, calls the deal “a significant U.S. diplomatic achievement that has ended hostilities in Gaza.” For those keen on seeing the distinct ways the Trump diplomatic initiative was applauded, the administration compiled a list of quotes from various news sources and political figures. It is a testament to the sheer volume of praise, and the utter poverty of its discernment.

To appreciate the full cynicism of the performance, one need only glance at the earlier acts. Upon assuming power, this administration, with dreary predictability, continued to supply the props for genocide. During the presidential debate in June of 2024, Trump said that the aim of American policy should be to “let Israel finish the job” in Gaza; since he took office, this maxim seems to have guided his approach. American weapons—which Israeli officials have said their campaign is fully dependent on and could not continue without—are still being sent to Israel. They are then used with the stated intention of depopulating Gaza, with genocide being the methodology to achieve this.

That the goal is the ethnic cleansing of Gaza cannot be doubted. The intention to remove the Gazan population has been attested to by a myriad of Israeli officials. It’s the motivation for the erasure of Gaza’s infrastructure. When addressing a committee in the Knesset (Israeli Parliament), Benjamin Netanyahu said that they were “demolishing more and more homes” so the Palestinians would have “nowhere to return.” The “obvious result,” as Netanyahu phrased it, “will be the desire of the Gazans to emigrate outside the strip.” In March, the Israeli Security Council adopted a plan to establish a bureau within the Defense Ministry to oversee what they call the “voluntary departure” of Palestinians from Gaza.

And our American President? He did not recoil from this horror, he embraced it with enthusiasm. He saw in this desolation the perfect site for a “Riviera of the Middle East.” He endorsed the ethnic cleansing campaign and made clear his desire, once the population was properly disposed of, for the United States to acquire control of the territory. Israeli officials were, quite naturally, elated. The minister of environmental protection identified Trump as an agent sent to effectuate divine will; she said, “God has sent us the US administration, and it is clearly telling us–it’s time to inherit the land.” Trump was apparently viewed as the antithesis of Moses, facilitating the removal of people from the promised land rather than leading them in. Netanyahu began identifying the implementation of Trump’s proposal to be among his “clear conditions” for ending the war.

Upon entering office in January, the Trump administration managed to secure a brief pause in hostilities. Various conditions were agreed upon, including the release of hostages, the resumption of humanitarian aid, and the withdrawal of Israeli forces from some areas of Gaza. The Israelis at once began violating the deal, with the full acquiescence of the Trump administration. Aid was blocked from entering Gaza, Palestinians were still being killed by Israeli forces, and Netanyahu refused to allow the Israeli negotiating team to confer in good faith on how to move beyond the first phase of the agreement. When Israel unilaterally abandoned the cease-fire and resumed the slaughter, Trump and his officials deceptively blamed Hamas for the deal’s unraveling.

This has been a recurring maneuver: in May, Hamas accepted the framework, which had been established by the Trump administration, for another ceasefire; the proposal was presented to the Israelis and was hastily disavowed. Administration officials then inverted blame for the plan’s failure, castigating the Hamas’s behavior as “disappointing and completely unacceptable.”

Trump’s efforts have achieved one objective: they have extended the genocide in Gaza and increased the number of its victims. He provided the weapons needed to maintain the slaughter, proposed his own plan for ethnic cleansing, diplomatically supported Israel when it sabotaged agreements to end the violence, vetoed United Nations resolutions calling for an end to the massacre, and sanctioned the International Criminal Court for issuing arrest warrants for Israeli officials. Now that he perceives his interests to have changed, he leveraged his support for Israeli violence to compel Israel’s agreement to a ceasefire—an agreement that could have been achieved long ago. Perhaps commentators at major news outlets could retain at least a modicum of integrity by not offering praise for this?

Why Should the Arabs Not Make Peace?

The Prime Criminal, David Gruen (Ben-Gurion), Explains

by Amel-Ba’al / November 11th, 2025

Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French. It is wrong and inhuman to impose the Jews on the Arabs. What is going on in Palestine today cannot be justified by any moral code of conduct. The mandates have no sanction but that of the last war. Surely it would be a crime against humanity to reduce the proud Arabs so that Palestine can be restored to the Jews partly or wholly as their national home.

—Mohandas K. Gandhi

The settlement of every question, whether of territory, of sovereignty, of economic arrangement, or political relationship, rests upon the basis of the free acceptance of that settlement by the people immediately concerned, and not upon the basis of the material interest or advantage of any other nation or people which may desire a different settlement for the sake of its own exterior influence or mastery. If that principle is to rule, and so the wishes of Palestine’s population are to be decisive as to what is to be done with Palestine, then it is to be remembered that the non-Jewish population of Palestine – nearly nine-tenths of the whole – are emphatically against the entire zionist program. The tables show that there was no one thing upon which the population of Palestine were more agreed upon than this. To subject a people so minded to unlimited Jewish immigration, and to steady financial and social pressure to surrender the land, would be a gross violation of the principle just quoted, and of the People’s rights, though it is kept within the forms of law.

—Woodrow Wilson

The principles of self-determination and justice, articulated by figures as diverse as Mahatma Gandhi and Woodrow Wilson, provide a clear moral framework for assessing the struggle over Palestine. Yet, the most damning indictment of the zionist project comes not from its critics, but from a stunning confession by one of its principal architects—a confession that systematically dismantles its own moral, theological, and historical justifications to reveal a foundation of raw power and lies.

A Loaded Zionist Confession

David Gruen, a Polish zionist who changed his name to Ben-Gurion, like most zionists who adopted “Hebrew” names to embed themselves in an imagined ancient history, said the following:

Why should the Arabs make peace? If I was an Arab leader I would never make terms with Israel. That is NATURAL: we have taken their country. Sure, God promised it to us, but what does that matter to them? Our God is not theirs. We come from Israel, it’s true, but two thousand years ago, and what is that to them? There has been anti-Semitism, the Nazis, Hitler, Auschwitz, but was that their fault? They only see one thing: we have come here and stolen their country. Why should they accept that? They may perhaps forget in one or two generations’ time, but for the moment there is no chance. So it’s simple: we have to stay strong and maintain a powerful army. Our whole policy is there. Otherwise the Arabs will wipe us out.

Sentence-by-Sentence Analysis

“Why should the Arabs make peace? If I was an Arab leader I would never make terms with Israel.”

Analysis: This opening is a stunning act of rhetorical empathy. Gruen correctly identifies the Palestinian resistance not as irrational hatred, but as a rational, national response to a threat. This admission is powerful because it comes from the architect of the state, immediately validating the core Palestinian grievance.

“That is NATURAL: we have taken their country.”

Analysis: This is the most honest and damning sentence, in which he explicitly defines the zionist project as the taking of another people’s country. The word “NATURAL” is key—he acknowledges that the desire to resist occupation and colonization is a universal and justified human impulse. This single sentence validates the entire settler-colonial critique of zionism.

“Sure, God promised it to us, but what does that matter to them?”

Faulty Logic & Hypocrisy: Here, the foundational justification is presented and immediately dismissed as irrelevant. The hypocrisy is monumental because Gruen was a secular atheist. For him, “God” was not a divine authority but a cultural-national symbol to be weaponized.

Deeper Hypocrisy: This “God” and the stories of His promise were created by the ancient indigenous inhabitants of the land (Canaanites). A European secularist using this native mythology to justify displacing the natives (the Arabs of Palestine) is an act of profound narrative and historical theft.

“Our God is not theirs.”

Faulty Logic: This is a deliberate misrepresentation that creates a “clash of civilizations.” The God of the “Hebrew” Bible (Yahweh)—originally a Canaanite deity—and the God of Islam (Allah) are the same Abrahamic deity. This false dichotomy erases shared theological roots, as well as the existence of native Arab Christians (for whom it is the same God) and native Arab Jews, who have always understood this shared heritage. It’s a political move to construct two separate, incompatible “tribes,” positioning both religions—which are themselves products of the native Arab cultural achievements—as enemies.

“We come from Israel, it’s true, but two thousand years ago, and what is that to them?”

Faulty Logic: Again, a core zionist claim—historical connection—is raised by a Polish zionist and European settler-colonialist, only to be negated as a valid reason for the natives to accept their own displacement and uprooting. He admits that a 2000-year-old claim does not nullify the rights of the people living on the land now. This exposes the central contradiction of political zionism: it relies on an imaginary and invented European religious narrative of “ancient history” to justify a modern political project that requires the subjugation of the present-day population. Furthermore, Gruen himself debunked the myth of a wholesale exile by acknowledging that the native population remained and later converted to Christianity and Islam. He admitted that the Arabs were the “flesh and the blood of old Judeans,” as he wrote in a book he published in 1918 in New York with another zionist, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, titled Eretz Israel in the Past and in the Present. Yet when these same Arabs refused his “Jewish state” on their land, they had to be rendered alien to it and targeted for uprooting.

“There has been anti-Semitism, the Nazis, Hitler, Auschwitz, but was that their fault?”

Moral Schizophrenia: This is a critical moral admission. He rejects the notion that Palestinians should pay the price for European crimes, which exposes the injustice of using the Holocaust as a justification for the Nakba. The logic becomes: Our need for safety from European persecution is so dire that we must make another people suffer, even though we know it is not their fault. This perverse calculus was articulated plainly by zionist leader David Gruen himself, who chillingly stated: “If I knew that it would be possible to save all the children in Germany by bringing them over to England and only half of them by transporting them to Eretz Israel, then I opt for the second alternative. For we must take into account not only the lives of these children but also the history of the people of Israel.” Here, the instrumentalization of a genocide is made explicit: the lives of European Jewish children were secondary to the political goal of settler-colonial state-building in Palestine, revealing a movement that would use one catastrophe to legitimize the engineering of another. This is the heart of the colonial ‘sad necessity’ narrative—a narrative further complicated by the fact that zionists simultaneously collaborated with the very architects of that European persecution, as exemplified by the Haavara Agreement.

“They only see one thing: we have come here and stolen their country. Why should they accept that?”

Analysis: Gruen reiterates the core admission, summarizing the Palestinian perspective with flawless accuracy. He has now dismantled every potential moral (Holocaust guilt), theological (God’s promise), and historical (ancient connection) argument for why a Palestinian should accept the state of Israel. In doing so, Gruen merely echoes the clear-eyed, if brutal, diagnosis of other European zionist architects. A decade and a half earlier, the Russian zionist Vladimir Jabotinsky laid bare the same immutable colonial logic, writing: “Every native population in the world resists colonists as long as it has the slightest hope of being able to rid itself of the danger of being colonised. That is what the Arabs in Palestine are doing, and what they will persist in doing as long as there remains a solitary spark of hope.” Jabotinsky, like Gruen, understood that no rhetorical smokescreen could obscure the fundamental conflict, noting: “We may tell them whatever we like about the innocence of our aims… but they know what we want, as well as we know what they do not want. They feel at least the same instinctive jealous love of Palestine, as the old Aztecs felt for ancient Mexico, and the Sioux for their rolling Prairies.” This acknowledgment of a universal, instinctive love for one’s homeland—from Aztecs to Sioux to Palestinians—proves the Palestinian resistance to be not a unique animus, but a rational and just defense against colonization, a natural law of human history understood all too well by the colonizers themselves.

“They may perhaps forget in one or two generations’ time, but for the moment there is no chance.”

Colonial Logic: This reflects the classic settler-colonial immoral hope that the natives will eventually be defeated, dispersed, or culturally erased enough that they (or their descendants) will ‘forget’ their claim to the land—a strategy of managing resistance through sustained power and erasure rather than addressing the injustice. The Palestinians, like indigenous peoples everywhere, have repeatedly proven the profound arrogance of this logic wrong.

“So it’s simple: we have to stay strong and maintain a powerful army. Our whole policy is there. Otherwise the Arabs will wipe us out.”

The Ultimate Revelation: Having demonstrated that the project is morally corrupt and unjustifiable to its victims, the Polish political architect arrives at the only logic left: raw power. Since persuasion is impossible, perpetual domination is the only solution. “Our whole policy is there” is an admission that the state is founded on a security doctrine meant to manage the consequences of its own original injustice, not to resolve it. Peace is replaced by the permanent threat of force. The statement “Otherwise the Arabs will wipe us out” is the ultimate justification for this posture, framing a defensive national struggle against colonization as an existential threat, thus completing the circular logic of militarism.

From Theory to Blueprint: The Iron Wall Consensus

This ultimate revelation—that the project’s sustainability depends on perpetual military dominance—exposes the foundational consensus between the so-called left-wing and right-wing strands of zionism. While later political narratives would paint them as adversaries, their diagnosis of the core conflict was identical. Gruen’s conclusion is merely a pragmatic affirmation of the doctrine Jabotinsky had articulated years earlier in his 1923 article, “The Iron Wall (We and the Arabs)”: “If you wish to colonize a land in which people are already living, you must provide a garrison for the land, or find a benefactor who will maintain the garrison on your behalf. zionism is a colonizing adventure and, therefore, it stands or falls on the question of armed forces.” The “Iron Wall” was not a controversial strategy but an operational blueprint, acknowledging that the native population would never acquiesce to their own displacement and must be subdued by unassailable force.

The Hypocrisy of Successor zionists: From Private Admission to Public Denial

The confession of David Gruen serves another critical function: it exposes the profound hypocrisy of later zionist leaders who, once the state was established, traded this brutal honesty for public disinformation. While Gruen privately admitted to taking a country, his successors publicly denied the very existence of its people. Golda Myerson (Meir), another Russian zionist and secular atheist, exemplified this shift, employing whatever argument served the moment, from cynical jokes to outright erasure.

On the foundational injustice, she oscillated between flippancy and fatalism. She was widely quoted making light of the situation with her famous quip, “Let me tell you something that we Israelis have against Moses. He took us 40 years through the desert in order to bring us to the one spot in the Middle East that has no oil!” Elsewhere, the Russian zionist expressed a more fatalistic resolve, declaring in a 1973 speech, “We Jews have a secret weapon in our struggle with the Arabs; we have no place to go.”

Most notoriously, she flatly denied the foundational crime that Gruen had confessed to, asserting the racist myth of a land without a people: “It is not as though there was a Palestinian people … and we came and threw them out and took their country away from them … they did not exist.”

Yet, when convenient, this secular leader did not hesitate to invoke the divine promise that Gruen had dismissed as irrelevant to the Arabs: “This country exists as the fulfillment of a promise made by God Himself. It would be ridiculous to ask it to account for its legitimacy.”

The contrast could not be starker. Gruen’s private confession reveals a zionist who understood the moral cost of his settler-colonial project. Myerson’s public statements reveal a regime reliant on a web of contradictory myths—simultaneously mocking divine providence while wielding it, and denying the existence of a people whose land its founder admitted to taking. This is the evolution of the zionist logic: from the raw confession of the conqueror to the polished fiction of the occupation state.

The Importance of This Confession

This statement transcends mere observation; it is a foundational confession. It unveils the inner logic and hypocrisy of zionism from the perspective of its principal architect. It serves as irrefutable evidence that the struggle’s core is not a “tragic” clash between two equal national rights, but rather the rational defiance of a native people against a European settler-colonial project—a project whose architects understood perfectly its oppressive nature.

This confession:

- Admits to the fundamental injustice, defining the zionist project explicitly as the appropriation of another people’s homeland

- Exposes its own justifications as cynical and hypocritical, demonstrating they serve as tools for mobilization rather than genuine moral arguments

- Concedes the rationality and justice of the native resistance, validating the Palestinian perspective as legitimate

- Concludes that raw power is the only remaining logic, asserting that since the project is morally unjustifiable, it must be maintained through perpetual military domination

The confession of David Gruen is the skeleton key that unlocks the true, amoral logic of an outpost state built not on right, but on deception and might.

ENDNOTES: