Turning point, apocalypse or renewal: what will the blood moon bring to Europe?

The moon has fascinated people since time immemorial. This weekend it's that time again: a blood-red full moon appears in the night sky.

The blood moon, otherwise known as a total lunar eclipse, has been surrounded by superstition for centuries - often with dark or apocalyptic connotations.

In many cultures - from Babylon to China to Central America - the blood moon was interpreted as a threatening sign: for the death of rulers, impending wars, natural disasters or "divine punishments".

In some African cultures, on the other hand, it is seen as a sign of "renewal". The Batammaliba, a West African ethnic group in Togo and Benin, interpret a lunar eclipse - especially a "blood moon" - as a symbolic battle between the sun and the moon. They try to resolve conflicts - and "reconcile the sun and the moon" - by creating peace in their communities.

For astronomers and astrologers of our time, this event is equally interesting - even if opinions are divided here again.

Longest lunar eclipse in years

On Sunday, we are now facing a total lunar eclipse - at around 82 minutes, the longest since 2022.

The Earth will be exactly between the sun and the moon. Its shadow will fall completely on the moon, darkening it. Only red-coloured light penetrates the Earth's atmosphere and falls refracted onto the moon - hence its reddish appearance and the popular term "blood moon".

Dr Florian Freistetter, an astronomer and science writer says from a scientific point of view, there is not much left to observe about the eclipses: "Astronomy has researched everything that can reasonably be researched in the last century. But that also means that I can enjoy the sight of an eclipse in peace without having to worry about science."

Keyword "science": In antiquity and the Middle Ages, astrology and astronomy were not separate - both were concerned with the observation of celestial bodies and existed side by side with their different interpretations. Astrology was practised from Babylon to Greece, India and the Arab world and was an integral part of medicine, philosophy, the church and politics.

The Age of Enlightenment brought about a turning point

This changed with the Age of Enlightenment, an era that lasted from around the 16th to the 18th century. It originated in Europe and later spread worldwide.

French philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650) played a key role in this intellectual movement, which above all declared reason to be the basis of thought: "I think, therefore I am". Astrology, which deals with the significance of the position of celestial bodies for earthly events, contradicted a view of nature in which there was nothing that could not be explained physically and therefore no longer fitted in with the dominant view of science.

Rousseau: an outdated image of women today

Incidentally, many Enlightenment thinkers, including Kant, Rousseau and Voltaire, also held the idea that women were inherently less rational and therefore better suited to the family and raising children. For Rousseau, women were primarily mothers and companions, not equal citizens.

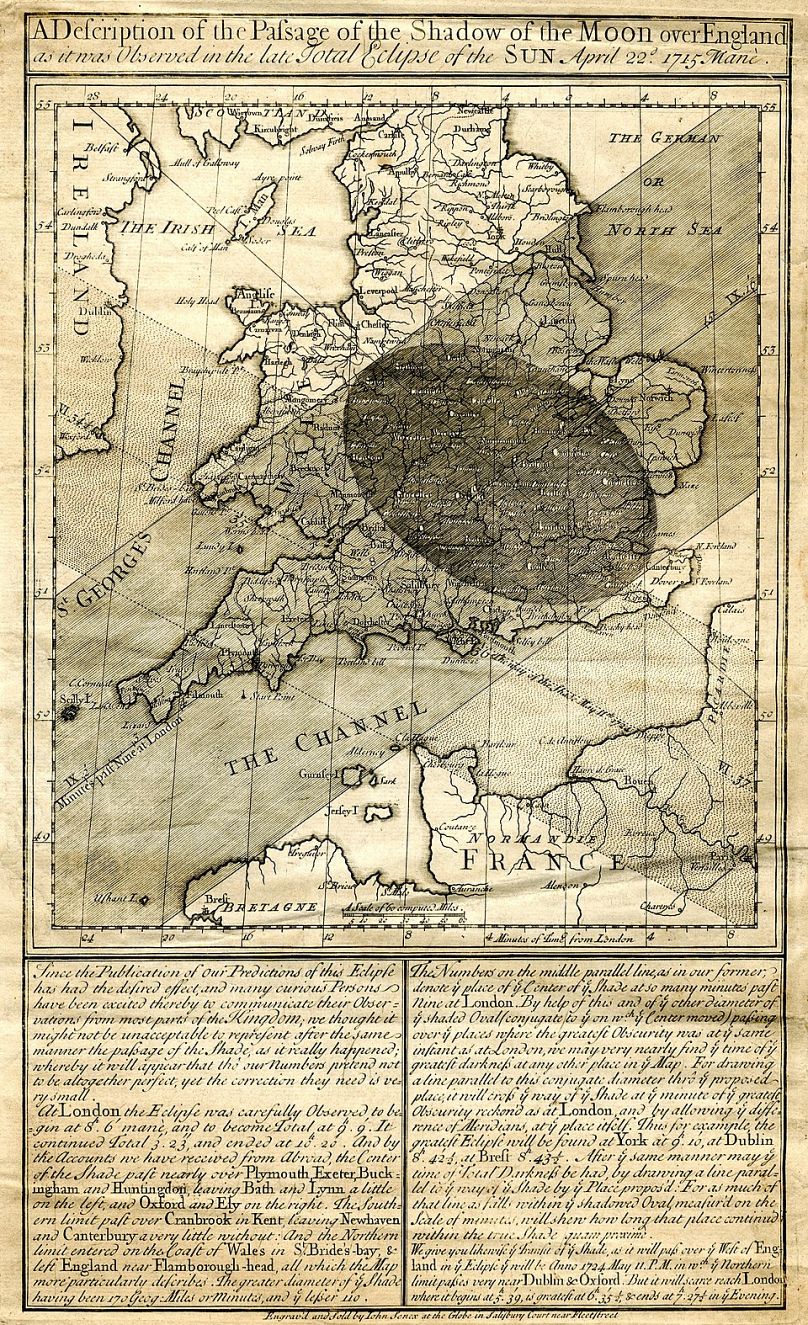

Image of the Moon’s shadow over England during a total solar eclipse on the morning of April 22, 1715. University of Cambridge, Institute of Astronomy Library (Edmond Halley, astronomer, mathematician, cartographer, geophysicist, and meteorologist, 1656–1742)

Dr. Gerhard Meyer, a qualified psychologist and researcher in the Department of Empirical Cultural and Social Research at his Institute for Frontier Areas of Psychology in Freiburg, explains that this was an era in which man's relationship with nature changed significantly. "The idea that the world can be understood as a machine that functions according to mechanical principles became dominant for science - with physics as a leading science."

At the same time, however, a parallel current emerged at the end of the 17th century: the age of Romanticism. Its followers rejected a mechanistic view of the world and were interested in the soul, the unconscious and also the invisible and only tangible.

Dr Meyer believes that astrology can be scientifically investigated, as "the underlying planetary movements are regular and predictable. The problem is the high complexity of the interrelationships." He hopes that artificial intelligence (AI) will help to better deal with this complexity in the future.

"Esoteric nonsense"

For the astronomer Freistetter, astrology is simply esoteric nonsense: "There is absolutely no reason why the whole thing should work and why the apparent position in the sky of a few spheres of rock, metal and gas millions of kilometres away should somehow say something about our personal lives and our future."

Astrology cannot work because it is completely inconsistent: "There are no astrological rules that say which celestial bodies play a role in the horoscope and which do not," emphasises Freistetter.

Islamic clerics look for the new moon that marks the beginning of Ramadan at the observatory of Muhammadiyah University in Medan, Indonesia. 10 March 2024 Binsar Bakkara/Copyright 2024 The AP. All rights reserved.

Silke Schäfer, one of the best-known astrologers in the German-speaking world, who runs her own astrology school, disagrees: "This is a classic statement that often comes from astronomers who only have a superficial knowledge of astrology."

The rules of astrology are by no means arbitrary, but are learnt step by step in comprehensive specialist studies. For Schäfer, this is a cultural heritage that has existed "for over 2000 years with a clearly structured system of symbols". The basis is the zodiac with its 12 signs, which are based exactly on the ecliptic, i.e. the orbit of the earth around the sun. "There are clearly defined planetary rulers, aspect angles (conjunction, square, trine, etc.) and house systems."

Astrology vs. astronomy

And why should this work?

"Astrology describes correlations of meaning, not causal mechanics," explains Schäfer. "The planets don't 'cause' anything in the physical sense, but reflect rhythms, cycles and archetypes that can be observed in nature, history and biography."

The principle of analogy should not be confused with the causal logic of physics.

Psychologist Markus Jehle from Berlin, author of several specialised books on astrology, goes one step further: "We use planetary data from NASA for our software and the calculations we make are highly precise." The astronomers would use their arguments again and again to attract attention.

"After all, you can also measure air temperature in Celsius and Fahrenheit, so it doesn't negate the accuracy of the other unit of measurement."

Astronomers generally don't understand much about a "knowledge system of astrology", says Dr Mayer. "The ignorance here is on the part of the astronomers, because astrologers have known since ancient times that there is a precession of the vernal equinox: Astrology doesn't work with constellations, but with signs of the zodiac, which form a fictitious annual cycle divided into 30° sections."

Astrology is not a scientific experiment, adds Silke Schäfer, but a "hermeneutic", an art of interpretation. As with literary studies or psychotherapy, there are rules, but also room for interpretation.

"Instead of devaluing each other, it would be fruitful to recognise each other: Astronomy and astrology both deal with the heavens. Astronomy with the measurable facts, astrology with the meanings for us humans and evolution as a whole. The two complement each other and belong together. They always have."

France's ex-President Mitterand went to an astrologer

Are there any examples of contemporary politicians who have gone to astrologers? François Mitterrand, the longest-serving French president to date (1981-1995), regularly sought advice from Swiss astrologer Élizabeth Teissier - both on personal issues such as his health and on decisions relevant to the state, such as the Gulf War or the timing of the Maastricht referendum.

This Sunday, 7 September, the blood moon will be a total lunar eclipse that will be clearly visible in many parts of Europe. Some astrologers regard this event as a powerful full moon that can bring individual turning points. That which has had its day in life would clearly show itself so that it can be left behind. In their opinion, this has nothing to do with superstition.

For Dr Freistetter, eclipses are interesting and fascinating, but for a different reason: "Above all, it is an aesthetically impressive natural event and we are lucky to live on a planet where we can observe something like this. The Earth is in a unique position so that the sun and moon appear exactly the same size in our sky - coincidentally - and can therefore obscure each other."

One thing is certain: You can relax and enjoy this Sunday's lunar eclipse as a natural event: statistical studies show no connection between blood moons and (natural) disasters.