Europe isn’t just at risk of the direct effects of climate change, it is also exposed to the indirect effects of infectious disease like dengue, chikungunya and West Nile Virus – which are expanding their territories northward.

Issued on: 01/07/2025 -

FRANCE24

By:Diya GUPTA

Europe is unusually hot. Several cities in France have been placed on an ‘unprecedented’ high alert on Tuesday, Spain recorded a scorching high of 46 degrees Celsius on Monday while wildfires in Turkey caused by a heatwave have forced more than 50,000 people to be evacuated from five regions in the western province of Izmir.

While the heat is uncharacteristically strong, extreme weather is no longer a surprise. Science agrees that climate change caused by steadily increasing greenhouse emissions has been the primary factor for the scorching new reality that the world is forced to adapt to, be it heatwaves, floods, droughts or extreme cold.

While the cumulative meteorological changes might make life more difficult for people, bacteria, pathogens and viruses are thriving in a world that’s getting hotter and more humid. Climate change is bringing ‘tropical’, climate sensitive illnesses up north, into Europe, shifting the geography of global infectious disease.

The migration of disease

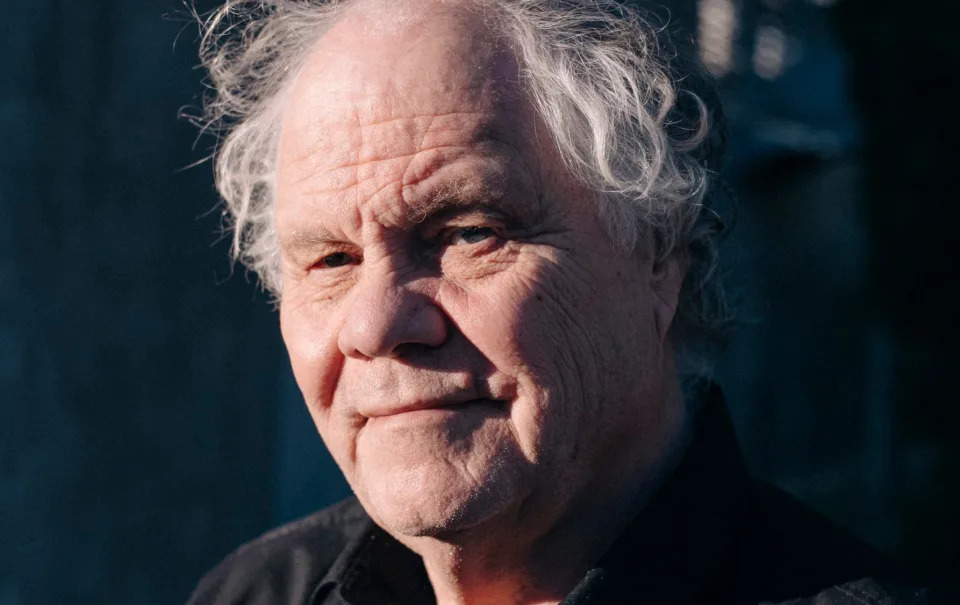

“Over half of all infectious diseases confronted by humanity worldwide have been at some point aggravated and even strengthened by climatic hazards,” says Dr Aleksandra Kazmierczak, an expert on the relationship between climate change and human health at the European Environment Agency (EEA).

Kazmierczak says that climatic conditions have made Europe more suitable for vector and water borne disease. ‘There is a northward, temporal shift because the current climate is more suitable for pathogens. Disease season is longer – ticks, for example, are now active all year round in many places.”

One of the fastest growing infectious diseases in Europe is dengue. 304 cases were reported in Europe in 2024 alone – compared to 275 cases recorded in the previous 15 years combined.

The main culprit behind dengue is the Asian tiger mosquito, or Aedes albopictus. The insect is what’s known as a vector, i.e. a living organism that can transmit infectious pathogens between humans or from animals to humans. With its distinctive black and white stripes that resemble those of a zebra more than a tiger, the mosquito is capable of transmitting dengue, zika and chikungunya.

Europe only experienced a handful of diseases carried by the tiger mosquito per year right up until the late 90’s. Most were one-off cases brought home by travelers from South East Asia – Aedes albopictus’s native home. But with increased travel and globalization, the insect’s journeys westward increased. It hopped onto cargo carriers to Albania or hitched a ride to the warmer parts of France and moved to Europe, where it remains to this day.

Read moreHow the tiger mosquito invaded France and what can be done to stop it

In 2006, France officially declared dengue a notifiable disease. In 2022, its presence was detected in most of the French mainland administrative departments. The insect quickly adapted itself to urban environments, where it needs just one still body of water – an undisturbed pond or a neglected watering can – to reproduce and proliferate.

The numbers have jumped so dramatically that scientists now believe that the diseases carried by Aedes albopictus will become endemic in Europe. Some researchers even say that the number of dengue and chikungunya outbreaks could increase five-fold by 2060 compared to current rates.

The tiger mosquito is a known carrier of several pathogens and viruses. Climatic conditions have contributed to a geographic range expansion of several other vectors like ticks and other species of mosquitos and flies, which carry their own diseases like West Nile Fever, Lyme disease and tick-borne encephalitis.

But unfortunately, it isn’t just the bugs we need to be worried about.

Climate change could also increase the occurrence of water-borne disease. In recent years, Europe has experienced the devastating impact of extended period of rain and floods, which wreak havoc on water treatment and distribution systems. Water can gather several pathogens from dumps, fields and pastures and flush them into water treatment and distribution systems.

Kazmierczak also warns of pathogens carried in the sea: "As the arctic melts; salinity in seawater decreases, making it ideal for pathogens like vibrio. It’s been seen more in the Baltic and North Seas. It is transferred from seafood or even exposure in an open wound if you’re swimming in infectious water."

Unearthing the zombie viruses

Permafrost covers almost 15 percent of the northern hemisphere, a significant portion of which is concentrated in Siberia, Alaska and Greenland. As the name implies, permafrost is soil and rock that stays frozen for at least two consecutive years. It acts almost like a cold storage for history: mammoths, saber-toothed tigers and long extinct plants have been preserved, almost entirely intact.

Some of what's stuck in frozen limbo isn't even dead – it's just dormant. Numerous ‘zombie microbes’ have been discovered in melting permafrost over the years, some after millennia. Researchers have raised fears that a new global medical emergency could be triggered – not by an illness new to science but by an ancient disease which modern human immunity is not equipped to deal with. The melting permafrost could also release old radioactive material and banned chemicals that had been dumped as waste.

This was the case in 2016, when over 2000 reindeer were found dead in Siberia because of an anthrax outbreak. Melting permafrost thawed the carcass of a reindeer that had died decades ago and unleashed the dormant virus into the modern world. Dozens of people living nearby had to be hospitalized.

This bizarre new threat may be another consequence of warming global temperatures, despite sounding like it’s been pulled from the pages of a science fiction novel. But Kazmierczak says that the research is still in its nascent stages and permafrost exists in isolated regions with little habitation.

Adapting to a new environment

The changes in the geography of infectious disease, to a large extent, cannot be undone. Temperatures in Europe have already risen by over 2 degrees in the last decade alone, with no sign of it slowing down.

But despite the warming climate, Kazmierczak is hopeful that Europe can adapt. “National health infrastructures and awareness will be paramount in our adaptation. We already have examples from countries that have already dealt with these illnesses, and we can adapt them to Europe.

“We believe that a way to reduce our carbon footprint is also to bring nature into cities and homes – but hosting vectors, for example, is exactly the flipside that it can have. We need to make sure that we adapt with awareness.”