Electrocardiogram in hospital surgery operating emergency room showing patient heart rate with blur team of surgeons background

A very significant change that happened in the last century or so has been the ability of science professionals to see what happens when people are thinking, especially under traumatic conditions.

It was not a good moment for materialist theories. Here is one finding (there are many others): Death is a process, usually, not simply an event.

Consciousness can persists after clinical death. A more accurate way of putting things might be that the brain is able to host consciousness for a short period after clinical death. Some notes on recent findings:

The short answer is, probably, yes:

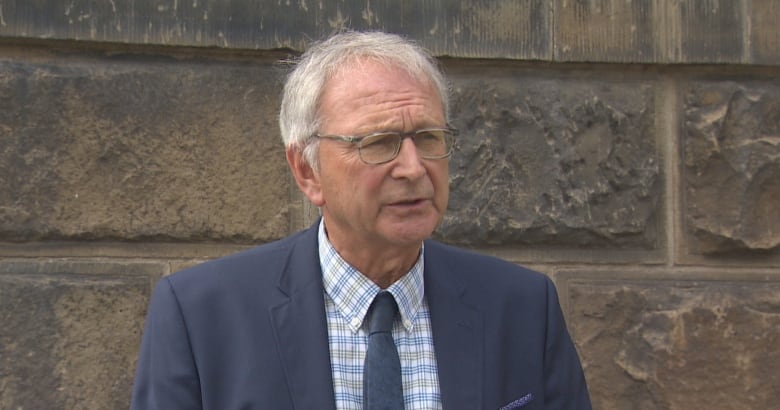

Recent studies have shown that animals experience a surge in brain activity in the minutes after death. And people in the first phase of death may still experience some form of consciousness, [Sam] Parnia said. Substantial anecdotal evidence reveals that people whose hearts stopped and then restarted were able to describe accurate, verified accounts of what was going on around them, he added.

“They’ll describe watching doctors and nurses working; they’ll describe having awareness of full conversations, of visual things that were going on, that would otherwise not be known to them,” he explained. According to Parnia, these recollections were then verified by medical and nursing staff who were present at the time and were stunned to hear that their patients, who were technically dead, could remember all those details.

Death is probably, in most cases, a process rather than a single event:

Time of death is considered when a person has gone into cardiac arrest. This is the cessation of the electrical impulse that drive the heartbeat. As a result, the heart locks up. The moment the heart stops is considered time of death. But does death overtake our mind immediately afterward or does it slowly creep in?

Some scientists have studied near death experiences (NDEs) to try to gain insights into how death overcomes the brain. What they’ve found is remarkable, a surge of electricity enters the brain moments before brain death. One 2013 study out of the University of Michigan, which examined electrical signals inside the heads of rats, found they entered a hyper-alert state just before death.

Despite claims, current science does not do a very good job of explaining human experience just before death:

Researchers have also explained near-death experiences via cerebral anoxia, a lack of oxygen to the brain. One researcher found air pilots who experienced unconsciousness during rapid acceleration described near-death experience-like features, such as tunnel vision. Lack of oxygen may also trigger temporal lobe seizures which causes hallucinations. These may be similar to a near-death experience.

But the most widespread explanation for near-death experiences is the dying brain hypothesis. This theory proposes that near-death experiences are hallucinations caused by activity in the brain as cells begin to die. As these occur during times of crisis, this would explain the stories survivors recount. The problem with this theory, though plausible, is that it fails to explain the full range of features that may occur during near-death experiences, such as why people have out-of-body experiences.

Such explanations are a classic case of adapting a materialist hypothesis to fit whatever has happened. They don’t explain, for example, terminal lucidity, where many people suddenly gain clarity about life.

Research medic Sam Parnia found, for example, that, of 2000 patients with cardiac arrest,

Some died during the process. But of those who survived, up to 40 percent had a perception of having some form of awareness during the time when they were in a state of cardiac arrest. Yet they weren’t able to specify more details.

So we should not assume that people who are on the way out cannot understand us. Maybe they can — and would like to hear that they are still loved and will be missed.

You may also wish to read: Do people suddenly gain clarity about life just before dying?