REVIEW: This Doc on Mexico’s Private Ambulances is a Frightening Look at a Broken Healthcare System

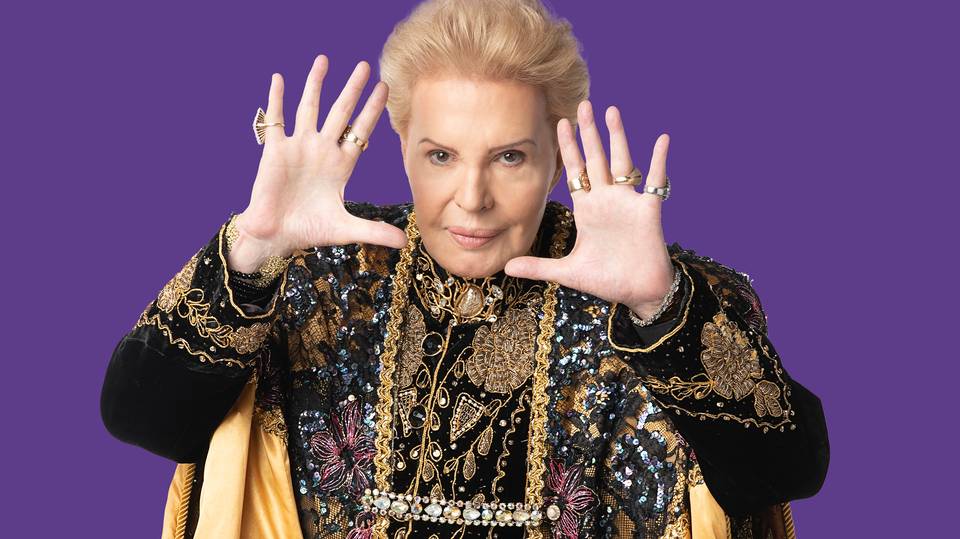

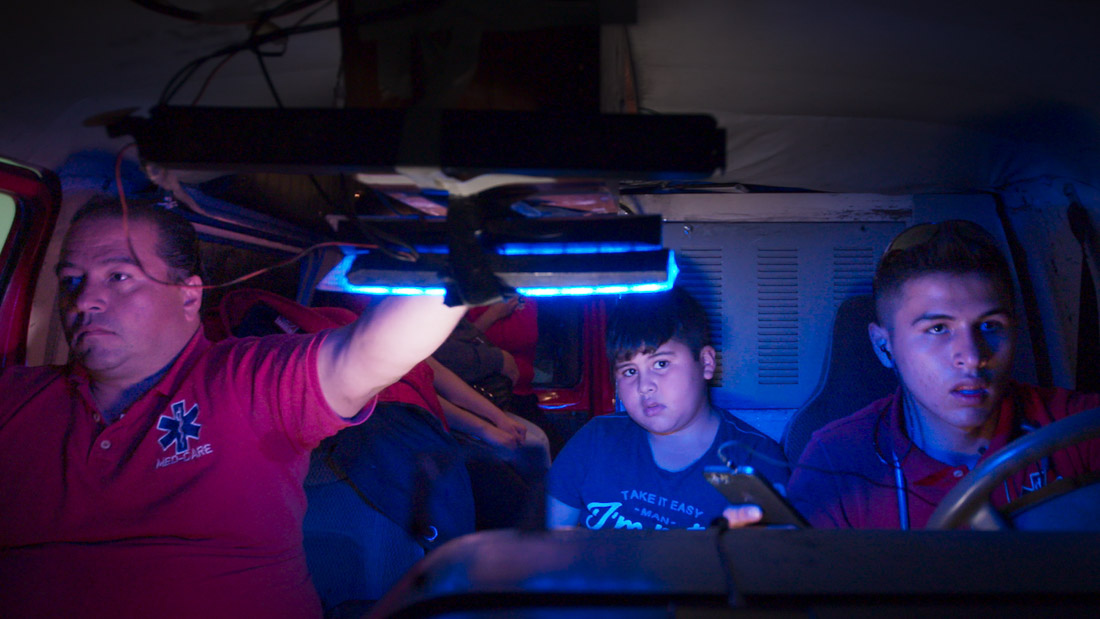

A still from Midnight Family by Luke Lorentzen,

an official selection of the U.S. Documentary Competition

at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival.

Courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by Luke Lorentzen

By Manuel Betancourt

“In Mexico City, the government operates fewer than 45 emergency ambulances for a population of 9 million. This has spawned an underground industry of for profit ambulances, which are often run by people with little or no training or certification.” That is the context we’re offered by Luke Lorentzen’s documentary Midnight Family. It’s a mind-blowing statistic and one which colors everything that follows. Opting for a cinema verité style, Lorentzen’s follows the Ochoa family as they work sleepless nights in the cramped private ambulance they operate. Offering little to no contextual info, we see them scouring emergency calls to find potential patients/clients. A static camera in front of the ambulance gives us as objective a view of the proceedings as possible, while Lorentzen, usually in the back of the ambulance with his camera, is often running around capturing the boys in action while they clean blood off their equipment, carry patients onto the back of the ambulance, and later deal with hospital bureaucracy and family members to secure whatever meager earnings they can muster.

“Is this expensive?” That’s the first question a young woman utters when the Ochoa family’s ambulance crew arrives to help her. She’s bleeding, crying, and a tad disoriented. Those treating her ignore her question, urging her instead to tell them how she got her head wound (an angry boyfriend who’s fled the scene), whether she has insurance (she doesn’t) and if she agrees to have them contact her family (they end up calling her mother). “Is this expensive?” she pleads again. The question hangs in the air and everyone’s decision to not answer her point-blank feels like an answer in itself. That silence over the cost of the ambulances’ services gets at the tricky and oft-unsavory ethical issues at stake in running a private ambulance service — especially one which, as we slowly learn, gets a cut from a specific (private) hospital when they deliver patients there.

A still from Midnight Family by Luke Lorentzen, an official selection of the U.S. Documentary Competition at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. Courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by Luke Lorentzen

Juan, the young, entrepreneurial sixteen year-old who seems intent on making this family business a legit one, tells the camera over and over again that he doesn’t understand why people (including the police in several instances) wouldn’t just agree to be helped and pay them in turn. Government ambulances aren’t showing up and they’re just trying to make a living. Why would people be concerned with their legality or their expenses at times when their lives are literally on the line? He doesn’t get it. It’s obvious that Lorentzen does. Moreover, the Connecticut-born director nudges us to consider both the system that’s allowed these kinds of services to pop up in such a populous city, as well as the one that’s left Juan and his family with few other opportunities to thrive.

Juan may want his little brother to go to school (the latter refuses since he doesn’t have a pencil let alone a backpack) but he more often than not indulges him, bringing him on late-night runs where he tucks himself in the back of the ambulance. It’s arguably a choice that does as much to show how close the family is, as show just how ill-equipped the operation is when a 9 year-old is a stowaway in the backseat.

Lorentzen’s filmmaking is unfussy and near-surgical in its precision. At times it’s as thrilling as any action movie, at others as quiet as an intimate family drama. He balances reckless car chase scenes on nighttime streets where dueling ambulances try to be the “first” on the scene with gentler moments at the furniture-less home. That he doesn’t crowd the movie with talking heads or factoids about Mexican health care, speaks to his desire to merely document and observe. He offers up the Ochoas and their behavior and invites us to make our own judgments. Hard to watch, with an unspoken message that’s even harder to swallow, Midnight Family is an unflinching look at a broken system and the unseemly choices people make to merely survive.

Midnight Family screened as part of the Sundance Film Festival.

By Manuel Betancourt

“In Mexico City, the government operates fewer than 45 emergency ambulances for a population of 9 million. This has spawned an underground industry of for profit ambulances, which are often run by people with little or no training or certification.” That is the context we’re offered by Luke Lorentzen’s documentary Midnight Family. It’s a mind-blowing statistic and one which colors everything that follows. Opting for a cinema verité style, Lorentzen’s follows the Ochoa family as they work sleepless nights in the cramped private ambulance they operate. Offering little to no contextual info, we see them scouring emergency calls to find potential patients/clients. A static camera in front of the ambulance gives us as objective a view of the proceedings as possible, while Lorentzen, usually in the back of the ambulance with his camera, is often running around capturing the boys in action while they clean blood off their equipment, carry patients onto the back of the ambulance, and later deal with hospital bureaucracy and family members to secure whatever meager earnings they can muster.

“Is this expensive?” That’s the first question a young woman utters when the Ochoa family’s ambulance crew arrives to help her. She’s bleeding, crying, and a tad disoriented. Those treating her ignore her question, urging her instead to tell them how she got her head wound (an angry boyfriend who’s fled the scene), whether she has insurance (she doesn’t) and if she agrees to have them contact her family (they end up calling her mother). “Is this expensive?” she pleads again. The question hangs in the air and everyone’s decision to not answer her point-blank feels like an answer in itself. That silence over the cost of the ambulances’ services gets at the tricky and oft-unsavory ethical issues at stake in running a private ambulance service — especially one which, as we slowly learn, gets a cut from a specific (private) hospital when they deliver patients there.

A still from Midnight Family by Luke Lorentzen, an official selection of the U.S. Documentary Competition at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. Courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by Luke Lorentzen

Juan, the young, entrepreneurial sixteen year-old who seems intent on making this family business a legit one, tells the camera over and over again that he doesn’t understand why people (including the police in several instances) wouldn’t just agree to be helped and pay them in turn. Government ambulances aren’t showing up and they’re just trying to make a living. Why would people be concerned with their legality or their expenses at times when their lives are literally on the line? He doesn’t get it. It’s obvious that Lorentzen does. Moreover, the Connecticut-born director nudges us to consider both the system that’s allowed these kinds of services to pop up in such a populous city, as well as the one that’s left Juan and his family with few other opportunities to thrive.

Juan may want his little brother to go to school (the latter refuses since he doesn’t have a pencil let alone a backpack) but he more often than not indulges him, bringing him on late-night runs where he tucks himself in the back of the ambulance. It’s arguably a choice that does as much to show how close the family is, as show just how ill-equipped the operation is when a 9 year-old is a stowaway in the backseat.

Lorentzen’s filmmaking is unfussy and near-surgical in its precision. At times it’s as thrilling as any action movie, at others as quiet as an intimate family drama. He balances reckless car chase scenes on nighttime streets where dueling ambulances try to be the “first” on the scene with gentler moments at the furniture-less home. That he doesn’t crowd the movie with talking heads or factoids about Mexican health care, speaks to his desire to merely document and observe. He offers up the Ochoas and their behavior and invites us to make our own judgments. Hard to watch, with an unspoken message that’s even harder to swallow, Midnight Family is an unflinching look at a broken system and the unseemly choices people make to merely survive.

Midnight Family screened as part of the Sundance Film Festival.

---30---