Illustrated | iStock/d_rich, iStock/Vadzim Kushniarou, Keystone Features/Getty Images

April 8, 2020

For the past week, I've been making fabric masks. I didn't want to, even as my fellow American sewists joined craftivist collectives and bought up the country's entire supply of braided elastic. But in this time of rapidly-changing and conflicting information, the CDC has abruptly conceded the wisdom of wearing masks in public, an about-face in messaging from "unnecessary and ineffective" to "probably crucial, and certainly better than nothing."

So I've been sitting down every day at my sewing machine, with a pile of quilting cotton scraps and a pattern printed from a stranger's blog. There's something almost sweet about this notion of contributing to the "war effort" while otherwise hunkering down at home — at least, if you ignore the terrifying implications of resorting en masse to making our own personal protective gear out of cotton scraps and hair ties.

But that sentimental filter obscures the sheer amount of work involved in making mask after mask — not just the manual labor, but also the mental strain of sifting through an internet's worth of muddled and conflicting information. Which mask style is best — boxy, pleated, or curved? Which of the zillion online patterns for each style is better? What fabrics are most suitable, or even remotely effective? Elastic or fabric ties? Twist ties, pipe cleaners, or skip the nose wire altogether? All while trying to source or substitute materials that are rapidly selling out everywhere.

And — you knew this was coming — I've noticed a pattern. Of the people I know who are making masks in enough volume to give them away, almost none is a cisgender (STRAIGHT/HETEROSEXUAL) man. In the realm of hobbies, sewing is perhaps one of the most strongly feminized. The push for fabric masks is being fueled by an army of female and non-binary sewists. Much of this labor is unrecognized; almost all of it is unpaid. The overall narrative involves goodness of hearts, housebound hobbyists getting their sewing fix with the side perk of saving the world.

It's not just masks, either. Now that so many of us have been driven indoors for the foreseeable future, we're getting an object lesson in just how much labor goes into holding our domestic lives together — and how gendered that balance of labor is. This is something that has long been rendered invisible in our cultural paradigms of crisis. In the words of journalist Laurie Penny, "emotional and domestic labor have never been part of the grand story men have told themselves about the destiny of the species."

I'm the first to admit the ways in which my privilege has colored these experiences. My cisgender male spouse and I both have white-collar jobs that can easily be done from home. We have health insurance and ample savings. We have access to everything we need, and many things we want, in order to shelter comfortably at home. Our nearest and dearest are, for the most part, in a similar boat. (And, it's worth acknowledging, we have historically outsourced some aspects of house maintenance — like periodic professional cleanings and handyman repairs — that would otherwise break along decidedly gendered lines.)

And yet, even in these relatively rarefied circumstances, I see inequities creeping in. My husband has done his best to step up around the house, both before and after coronavirus hit our shores. But it's not a 50-50 split. Take food, for example (already a gendered topic in our household). Now that we're charged with feeding ourselves at home for every single meal, we're trying to share the load. But I'm the one who knows how many cans of tuna we have in our pantry, or how long the broccoli has been in the fridge, or how many meals we can get out of a pound of pasta. When I'm on tap to figure out a meal, I'll cook (with all the cascading mental labor involved) or identify leftovers that need eating. When it's his turn, he opens a can of soup or orders takeout. The result is arguably the same — we get fed — but the amount of mental energy we're each willing to devote to the task is markedly different.

My friends and colleagues have voiced similar frustrations. The phrase "1950s housewife" is being thrown around with increasing regularity. With schools and daycares closed, many male-female co-parents I know have fallen into an achingly familiar pattern: the male partner focuses primarily on his job and pitches in when he has breaks, while the female partner attempts to homeschool and entertain the children while also fulfilling the bare minimum of her professional obligations, attempting to keep the house clean and get food into every belly in the house three times a day.

Even for the non-parents in my social circle, the labor of readying and maintaining a house for indefinite lockdown is not symmetrical. During our first week of sheltering in place, I made a frantic inventory of every item in our house that might run out in the near future, and figured out how much of each item to purchase (and from where) without tipping too far into hoarding territory. My husband focused on technology, setting up our living room and his office for near-constant video chatting. Again, the effort expended here is arguably similar; but the shape of the work, and the amount of the overall household mental load that it absorbs, is not.

This might sound trivial. But America, from its founding to its current late-stage catastrophe, has run on this kind of unacknowledged and under-compensated labor. As jobs like delivering mail or stocking store shelves become a matter of literal life and death, this machinery is suddenly harder to ignore. And gender is far from the only axis along which these inequities run. But every little bit is worth paying attention to. And this invisible labor is not simply a matter of choice; it is spider-silk holding our households together in uncertain and frightening times. We do this work because we fear that if we didn't, it would not get done.

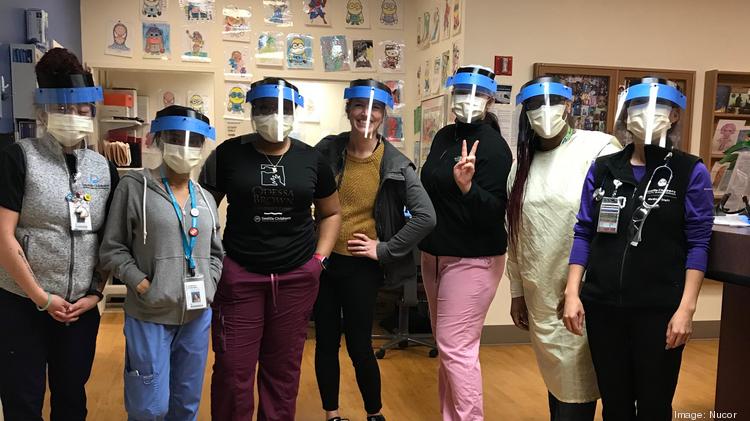

The CDC's recommendations for cloth masks include no explicit acknowledgement of how individuals are supposed to acquire them. But it does include instructions for making them oneself. The implication, to me, is clear: Someone in our lives is supposed to manufacture these masks for us by hand. Overwhelmingly, that "someone" will be a woman.