Yale Astronomers Questioned Systemic Racism Because They Hired One Black Employee 35 Years Ago,

AS OFFICE STAFF Emails Show

“Deeply entrenched systemic racism exists in every sector of our society, including at Yale and in this department,” a group of undergraduates wrote in response.

Stephanie M. LeeBuzzFeed News Reporter

Last updated on June 16, 2020

Checkmate24 / Wikimedia

Steinbach Hall on Yale's campus, which is home to the astronomy department.

Last Wednesday, as thousands of researchers across the world stopped work to protest racism in science, Yale astronomy professors expressed doubts that “deeply entrenched systemic racism” existed in their department — by pointing to their hiring of a single Black employee in 1985.

“We haven’t seen many Ella Greenes,” wrote Richard Larson, a professor emeritus, in an email to the astronomy department on the day of the strike, referring to the administrative employee whom he said was its first, and so far only, Black office staffer. “But Ella was an ambitious and self-made person, and she didn’t receive and didn’t need any special help for black people.”

In the email exchange, which was obtained by BuzzFeed News, Larson also questioned a colleague’s assertion that systemic racism existed in the department. “Whatever you want to say about ‘deeply entrenched systemic racism,’” he wrote, “Ella was not defeated by it.”

Students and researchers condemned these remarks in response, saying that the hiring of one Black person does not cancel out the department’s historic lack of racial diversity, and that the racist emails were indicative of how Black people are systematically excluded from science.

“If people of color do not feel comfortable in the department (and the current state of representation indicates they do not), it is due to our lack of trying,” a group of undergraduates wrote to the email chain.

Another professor emeritus, William van Altena, argued that the department’s lack of Black students and faculty members was due to the fact that those scholars had less interest in the physical sciences compared to the social sciences — “not due to inherent racism in our Department.”

In 2014, Jedidah Isler became the first Black woman to receive a PhD from Yale’s astronomy department. Now an assistant professor of astrophysics at Dartmouth, Isler told BuzzFeed News that the emails from the Yale professors were “infuriating but not at all surprising,” because “structural and interpersonal racism runs rampant at Yale.”

Xama Señal UNSJ / Via youtube.com

William van Altena

“The fact that senior members of the department feel comfortable making such intellectually dishonest and violent comments about Black people given the historical practices — at Yale — is itself a demonstration of structural oppression,” Isler said by email.

The chair of the Yale astronomy department, Sarbani Basu, declined to comment on any of the emails cited in this story and did not address the concerns raised by Isler.

“The listening session you mentioned in your inquiry was a private event organized by students and faculty. It served as one of multiple forums in which students, postdoctoral associates, faculty and staff are expressing their viewpoints on this important issue,” Basu said through a spokesperson. “We take these conversations seriously and will use their feedback to help inform and enlighten our ongoing work to increase diversity in the sciences.”

The heated discussion has roiled the prestigious department at a time when academia, along with virtually every other institution in American life, is scrutinizing its role in perpetuating discrimination against and exclusion of Black people.

The recent police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black Americans have galvanized weeks of protests against police brutality and racism in all 50 states, triggered a flood of funding and support for the Black Lives Matter movement, resulted in teardowns of Confederacy leader statues, and prompted the resignations of corporate executives with histories of racist behavior.

During last Wednesday’s “Strike for Black Lives,” thousands of scientists stopped research to protest anti-Black racism, come up with ways to address inequalities within their departments, and fill social media with hashtags like #ShutDownSTEM and #ShutDownAcademia. And hundreds of Black scientists used the hashtag #BlackInTheIvory to describe the racism they have faced in their careers. That afternoon, members of Yale’s astronomy department planned to take part by holding a Zoom town hall meeting to discuss racial equality.

Astronomy as a field is overwhelmingly dominated by white men, and research shows that women, especially women of color, face greater risks of gendered and racial harassment on the job. A 2018 survey of the American Astronomical Society — which includes undergraduates, graduate students, faculty members, and retired astronomers — found that 82% of members identified as white and only 2% as Black or African American. The same year, an AAS task force deemed the field’s lack of diversity “unacceptable” and “unsustainable.”

Basu, the Yale astronomy department chair, did not answer questions about how many Black graduate students have graduated from the department, or how many Black faculty and staff it has employed. Across the university, 7.7% of the student body identifies as Black or African American.

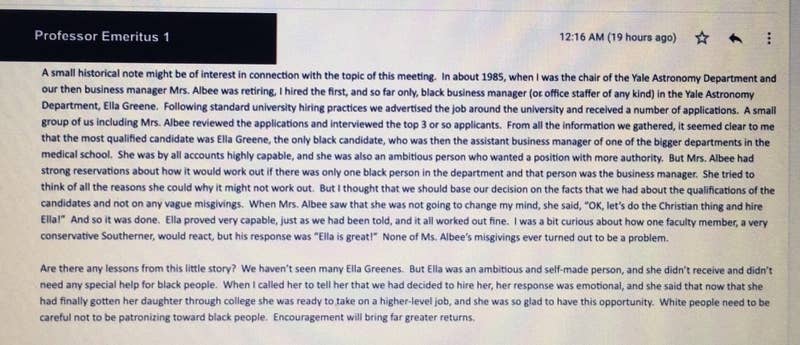

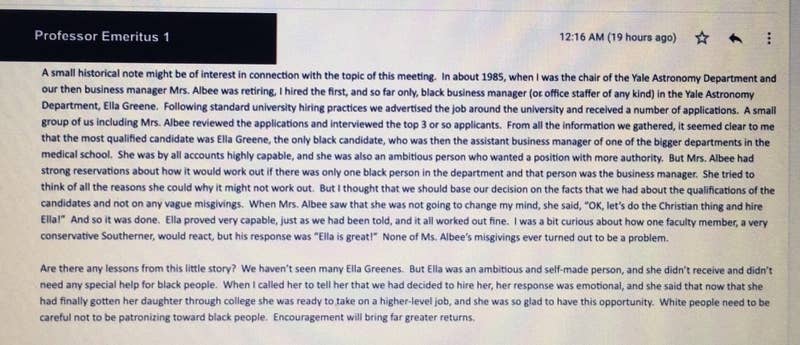

Before Yale’s town hall, Larson, the professor emeritus, took a few minutes to share a bit of history on the department mailing list. (His emails, and the others mentioned in this story, were sent to BuzzFeed News with names redacted. BuzzFeed News has confirmed several of the senders’ identities and other details.)

Larson recounted that when he was department chair in 1985, he hired a woman named Ella Greene, “the first, and so far only, black business manager (or office staffer of any kind) in the Yale Astronomy Department.”

A Yale spokesperson did not answer questions about Greene’s employment. BuzzFeed News was not able to reach Greene or a relative for comment.

“From all the information we gathered, it seemed clear to me that the most qualified candidate was Ella Greene, the only black candidate, who was then the assistant business manager of one of the bigger departments in the medical school,” Larson, who retired in 2011, continued. While he wrote that Greene’s predecessor worried “about how it would work out if there was only one black person in the department,” she “proved very capable, just as we had been told, and it all worked out fine.”

He went on: “Are there any lessons from this little story? We haven’t seen many Ella Greenes. But Ella was an ambitious and self-made person, and she didn’t receive and didn’t need any special help for black people.”

“White people need to be careful not to be patronizing toward black people,” he concluded. “Encouragement will bring far greater returns.”

Obtained by BuzzFeed News

An email from Richard Larson

Later that morning, van Altena, another professor emeritus, who retired in 2007 after 34 years in the astronomy department, chimed in to call Greene “one of our very best business managers.”

“I was never aware of any discrimination or negative feelings towards her within the Astronomy Department,” van Altena wrote. “My one regret is that despite repeated invitations for many years she never came to our Christmas parties so she must have felt some aspect of non non-acceptance [sic] but it was not due [to] our lack of trying.”

Throughout the rest of Wednesday, others in the department echoed that sentiment. An administrative employee called Greene a mentor and said she had only attended one party, perhaps due to a medical condition. And professor emeritus Pierre Demarque, who retired in 2001 and said he was on staff when Greene was hired, thanked Larson for his comments, particularly “about the lessons to draw.”

To a postdoctoral fellow, however, Larson’s portrayal was indicative of the racism in the department.

“[T]he statement that ‘we haven’t seen many Ella Greenes’ is evidence of the deeply entrenched systemic racism present in our society,” the postdoc wrote back. “It would be more productive to acknowledge that our department (and astronomy in general) remains highly non-representative of the overall population and instead focus the conversation on how those of us in positions of privilege and power can educate ourselves and do better in the future.”

Larson took offense at this suggestion.

“Whatever you want to say about ‘deeply entrenched systemic racism’, Ella was not defeated by it,” he wrote. “And I saw no evidence that it was a problem in our department or elsewhere at Yale. Yes, of course there are inequalities in our society and we all want to see them reduced. But I think you will do more good by helping and encouraging future Ella Greenes than by railing against racism and condemning people as racists.”

A graduate student then threw their support behind the postdoctoral researcher. “Systemic racism is universal in our country,” they wrote. “Although it may be true that it affects certain places more than others (but even this is debatable), it is unfortunately pervasive everywhere, even at Yale.”

That afternoon, in a cosigned letter to the department at large, a group of undergraduate students condemned the professors’ remarks as examples of “white saviorism” and “tokenism.”

“[B]oth of these phenomena can lead white people in positions of power to feel as if they have adequately addressed racism in their place of work, while the deeper foundational issues remain intact,” they wrote, stressing the importance of being anti-racist “instead of simply ‘not racist.’”

“To say that Ella ‘didn’t receive and didn’t need any special help for black people’ completely ignores the larger systemic issues that have for centuries barred non-white people from accessing the same opportunities as their white counterparts, in academia and beyond,” they continued. “We will not spend additional time proving the existence of systemic racism in America here, as we believe it should be evident to all that we still face a crisis in our country and our field and that deeply entrenched systemic racism exists in every sector of our society, including at Yale and in this department. Just because you do not personally see the effects of such inequity does not mean that it does not exist for others. To say otherwise is insulting and we encourage those who hold this opinion to spend some time reflecting on their privilege.”

“[T]he statement that ‘we haven’t seen many Ella Greenes’ is evidence of the deeply entrenched systemic racism present in our society.”

In return, Larson rejected the labels of “white saviorism” and “tokenism.”

“When I said that I didn’t see any evidence of ‘entrenched and systemic racism’ in our department, what I meant was that I did not see any behavior or hear any remarks in our department that could be called racist,” he explained.

He went on to argue that everyone is racist. “The real problem in dealing with racism is not that some particularly wicked people are racist, it’s that EVERYONE is racist, because racism is a part of human nature that is shared by every member of the species homo sapiens, regardless of skin color,” Larson wrote. And he doubled down on what he saw as the moral of his story: “Ella would have fiercely resisted any implication that she was special in any way because of membership in any group.”

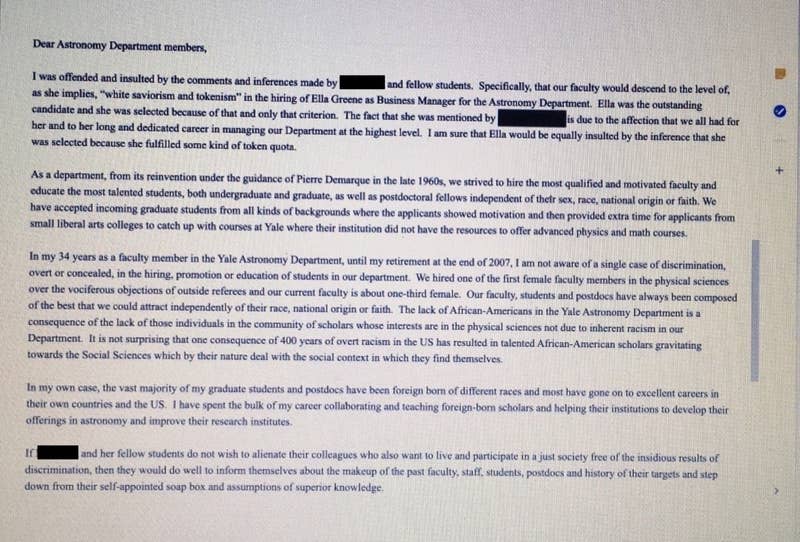

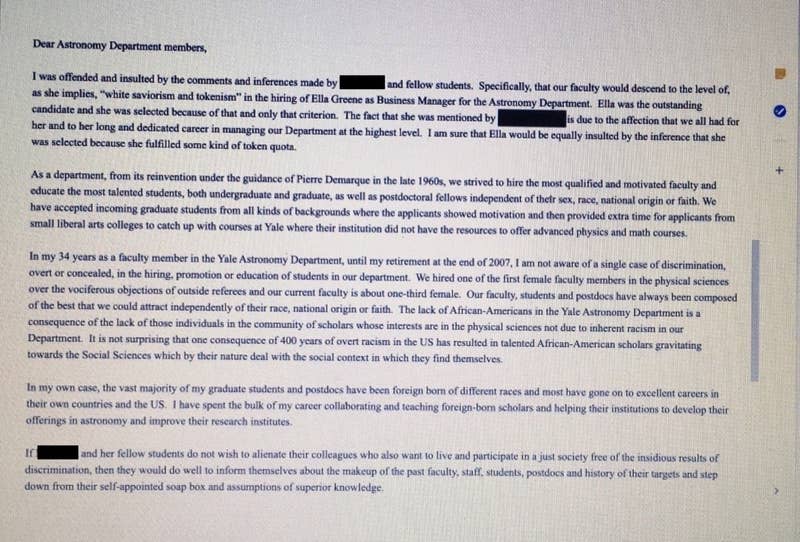

That evening, after the town hall, van Altena told the email thread that he was “offended and insulted” by the undergraduates’ words. He wrote that he was “not aware of a single case of discrimination, overt or concealed, in the hiring, promotion or education of students in our department.”

Rather, van Altena said, the lack of Black people in the department “is a consequence of the lack of those individuals in the community of scholars whose interests are in the physical sciences” and “not due to inherent racism in our Department.” He went on to say that Black scholars instead gravitate “towards the Social Sciences which by their nature deal with the social context in which they find themselves.”

The undergraduate students who sent the letter, he said, should “step down from their self-appointed soap box and assumptions of superior knowledge.”

In the exchange, the undergraduates and young researchers weren’t alone in pushing back against the retired professors. At least three current faculty joined them.

“Your remarks are hurtful to our community and do not comport with a vast body of data,” one professor wrote. “In our town hall today, I learned and listened to ways in which our department has systematically failed our students of color. It is not for lack of student interest that our department has not graduated more than a single Black PhD. I am ashamed of this fact and will work to do better.”

“Yale has a sorry history when it comes to these issues,” wrote another, “and we have to begin by acknowledging that if there is to be any progress.”

Obtained by BuzzFeed News

An email from William van Altena.

The following week, Larson and van Altena issued apologies that were shared with members of the department on Monday evening. “We recognize that the tone and some of what we had written in our emails prior to the Town-Hall have caused offense and hurt,” van Altena wrote. “That was not our intention, and we offer a sincere apology for this.”

But the problem runs deeper than the emails from last week, according to people who have worked with or studied in the department.

Isler, the alumnus who is now a Dartmouth astrophysicist, said the professors’ “arguments were neither good, accurate or even creative; they reflect the banality of white supremacy embedded in the blatant lie of meritocracy.”

“The claims that Larson and van Altena make about Ms. Ella Greene and by extension about the ‘quality’ of Black people who ‘deserve’ to be at Yale Astronomy are false on biological, sociological, organizational, developmental, historical and ethical bases, to name only a few disciplines that are themselves studied on the same campus,” she said by email.

One undergraduate student of color at Yale, who is majoring in astronomy and requested anonymity, told BuzzFeed News that the email chain was “unacceptable.”

“Academia is headed by professors who are much older than the rest of the country, and that’s meant really slow demographic and cultural shifts,” the student said. “I think that if you shine a light into most astro departments, you’d see a strong history of shutting us out.”

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, a cosmologist at the University of New Hampshire and equality activist, said that she was asked to lead a discussion about diversity during a scientific visit to Yale’s astronomy department in 2016. Later during the visit, she was told it couldn’t afford to hire any Black junior faculty members.

“While brazenly racist emails are messed up,” she said, “that department’s biggest problems around racism are not a couple of bad emails but rather are structural.” A Yale spokesperson did not answer questions about these allegations.

Obtained by BuzzFeed News

An email from Richard Larson.

Larson told BuzzFeed News that in retrospect, his comments questioning systemic racism sounded “dismissive” and that he should have “been more careful in [his] wording.”

“[C]learly for most of the students it is not enough to be not racist, you have to be vehemently anti-racist,” he said by email. “That is not my style.”

He noted that “because of recent events, the atmosphere around this subject has become so super-heated that it’s impossible to say anything without being attacked.” That climate, he said, reminds him of the year 1970. “Things have changed for the better in 50 years, but not as much as the activists of 50 years ago would have liked, and of course we still have big problems,” he wrote. “I think that the current activism is healthy and I wish it success. If you don’t see me out there marching, it doesn’t mean that I don’t support the cause.”

“Ella Greene herself would probably be mortified by all this,” Larson added. Asked whether his emails were racist, he said, “I will let people make their own judgement about whether anything is ‘racist.’”

Van Altena and Demarque declined to comment.

The department’s “climate and diversity” mission statement reads: “We embrace open communication and constructive discourse to cultivate a welcoming and collaborative community in which all voices are heard and respected. While we are working toward these goals, we are mindful of our conduct, representing our department in a thoughtful and appropriate manner within all professional settings.” A Yale spokesperson did not comment on whether the professors’ emails last week violated this mission statement.

While the undergraduate astronomy major said Larson’s and van Altena’s apologies “took far too long,” they expressed cautious optimism about the future.

They’re professors emeriti "that won’t be involved in future planning for our department, and the other faculty seem invigorated to shift the culture here,” the student said. “We have a lot of work to do this next year and beyond, but right now I’m hesitantly hopeful for what's to come.”

Azeen Ghorayshi contributed reporting to this story.

June 16, 2020

MORE ON THIS

Stephanie M. Lee · June 3, 2020

Adolfo Flores · June 12, 2020

Azeen Ghorayshi · July 10, 2017

Peter Aldhous · May 11, 2016

Stephanie M. Lee is a science reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in San Francisco.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66960759/144070513.jpg.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11904883/NERC_Interconnections_Color_072512.jpg) NERC

NERC:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20040811/Screen_Shot_2020_06_16_at_11.16.52_PM.png)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20043223/Screen_Shot_2020_06_18_at_10.13.52_PM.png)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20040871/map_seams.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20040895/Screen_Shot_2020_06_17_at_11.22.14_PM.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66941049/GettyImages_1182367639.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20037297/GettyImages_1214204203.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19893086/GettyImages_1217637327.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19945643/Screen_Shot_2020_05_04_at_10.24.49_PM.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66967486/GettyImages_1170903217.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20047403/GettyImages_1170468172.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66963353/526986110.jpg.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20045661/1193895665.jpg.jpg)